We like people who are understanding. They’re the people we want to be around, if anyone, when we feel low, sorry for ourselves, or bad because we’ve messed up. Being understanding is something that we praise in others, and it is something that we can be better or worse at. So the question is: how do we get better at it?

The answer is surprisingly difficult. Being understanding is only loosely connected to actually understanding what’s going on in another person’s mind. Think of a psychiatrist who is brilliant at her job of getting into the minds of others, but maintains a cold and distant attitude. We’d say she’s very good at ‘understanding others’, but not necessarily good at ‘being understanding’. Now think of a helpline worker. He is gentle, nonjudgmental, ready to listen to someone else’s troubles, but may not (yet) understand them well at all. Yet we’d call him understanding. So being understanding must be something over and above grasping the mental happenings of another person. What is it?

Being understanding is a virtue. Aristotle saw virtues as character traits that make us think, act and feel just right. Intellectual virtues make us think about things in the right way and come to know them. Moral virtues make us act and feel in the right way. A temperate person, for instance, will neither shy away from nor overindulge in the pleasures that good food and drink afford, but enjoy them in the right way. Aristotle defined moral virtues as golden means: the just-right medium between too little and too much feeling and motivation.

Being understanding is a somewhat curious case of virtue. It seems to have something to do with good thinking, with coming to understand another person correctly. But, as mentioned, being good at gaining knowledge of another person’s mind isn’t sufficient for an understanding attitude, though it might to some degree be necessary. This means that being understanding is not only, and perhaps not first and foremost, an intellectual virtue. Instead, it is largely a moral virtue. It’s to do with how we approach others, with the way we listen, with how accepting, empathic and helpful we are.

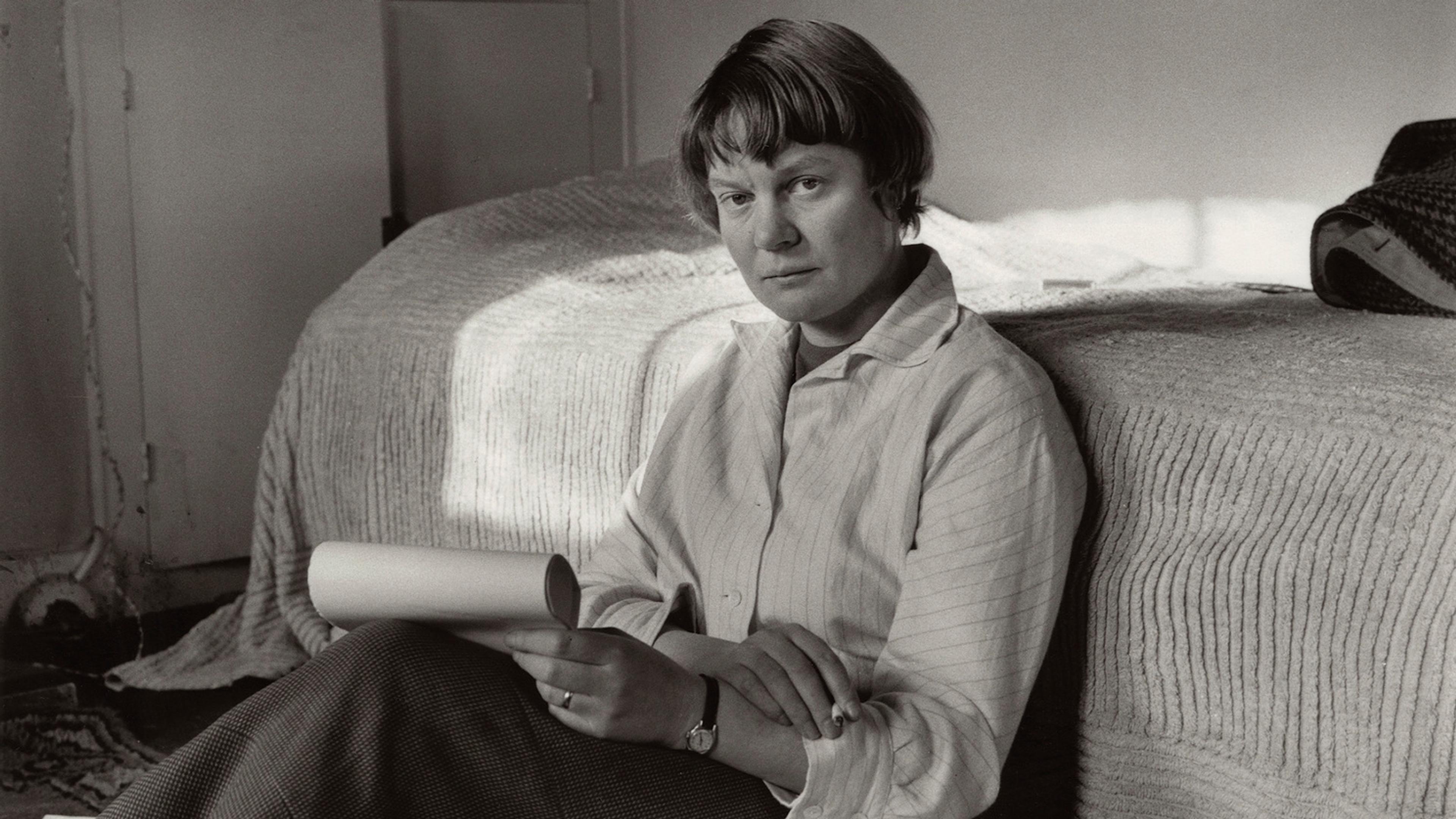

The Anglo-Irish philosopher Iris Murdoch (1919-99) held the view that learning to attend to others, to look at them justly and lovingly, is our main moral project in life. What matters is that we see people (and everything else) as they really are – a task as difficult as it is simple. The main difficulty is presented by our ‘fat relentless ego’, as she puts it. We usually look at the world in such a way as to protect and flatter ourselves. Our perception automatically makes light of the suffering of others, if our gaze goes in that direction at all. It dilutes criticisms and demands made of us, and it enhances what affirms our judgment, our reputation, our abilities. So, according to Murdoch, we have two difficult jobs to do: one is to get rid of these filters, and the other is to look again at the world in front of us. Getting better at one job will help with getting better at the other.

How should we go about it? In her essay collection The Sovereignty of Good (1970), Murdoch draws a parallel to the attention involved in learning new languages:

Attention is rewarded by a knowledge of reality. Love of Russian leads me away from myself towards something alien to me, something which my consciousness cannot take over, swallow up, deny or make unreal. The honesty and humility required of the student – not to pretend to know what one does not know – is the preparation for the honesty and humility of the scholar who does not even feel tempted to suppress the fact which damns his theory … Developing a Sprachgefühl [a sense for a language] is developing a judicious respectful sensibility to something which is very like another organism.

The object of attention in the case of being understanding is usually a person and their difficulties. A person and their difficulties are something alien to me. This does not mean that I might not relate to their trouble or have lived through something similar, but it means that their outlook on the world, their emotional biography and ways of thinking about things are something that, even with the utmost familiarity and good will, I will never entirely comprehend, not even close. There will always be parts of a person I don’t understand. And this is something of which we should remind ourselves, whether the person before us is in trouble or not: we must always approach others with an honest, humble acknowledgement of how hard it is to gain even a little knowledge about them.

Murdoch says that we shouldn’t ‘take over, swallow up, deny or make unreal’. With respect to another person and their difficulties, she means that we must neither think of them in the self-satisfied way that assumes we know what’s going on, nor should we look away because we don’t want to be bothered, telling ourselves it can’t be that bad after all. In order to be understanding, these are the two extremes between which we must navigate and where we must look for the golden mean.

Let’s take an example. Imagine your friend’s wife left him a couple of months ago. He still declines your invitations and remains sad and despondent whenever you see him. You are sorry for him, sure, but you begin to feel impatient. You think things like: ‘They were never really suited anyway, it’s for the best, really.’ ‘He really should try to be a bit cheerful.’ ‘He seems to quite like playing the role of the deserted husband, and it’s pretty tedious.’ So your invitations become less frequent and, a year later, you realise that you’ve become estranged. ‘Oh well, I’m sure he’s all right by now,’ you tell yourself. ‘He’s probably got a new girlfriend.’

In Murdoch’s terminology, your earlier reactions were instances of taking over and swallowing up. You presumed you knew how your friend felt and how he should be feeling, and that it was his fault for not getting better. You swallowed him up by making his reality fit your needs – because you ran out of patience, he was unreasonable and self-indulgent in his grief. Your later reactions were instances of denial and making unreal. Because you felt guilty, you presumed he was happy in his new life that didn’t include you any more, and that there was simply no need to think of him any longer.

We can now see what the right medium in the case of being understanding might look like. We must respect the reality of the other as something different, something not to be conquered, but something that is worth trying to get a feeling for – especially when they’re in difficulties. Respecting another person’s reality as different can be surprisingly hard, particularly when we know them well. Lifelong friends and siblings are good examples: they have overlapping biographies and similar traits, and know all about each other’s preferences and tastes. And yet they cannot know the other’s felt experiences from the inside. Simple as this insight is, we need to keep reminding ourselves of it. If we manage to practise virtuous attention successfully, the reward is ‘the extremely difficult realisation that something other than oneself is real,’ as Murdoch puts it. What we may hope for is that we gain a feeling for the other, similar to the Sprachgefühl that we may attain when learning a new language.

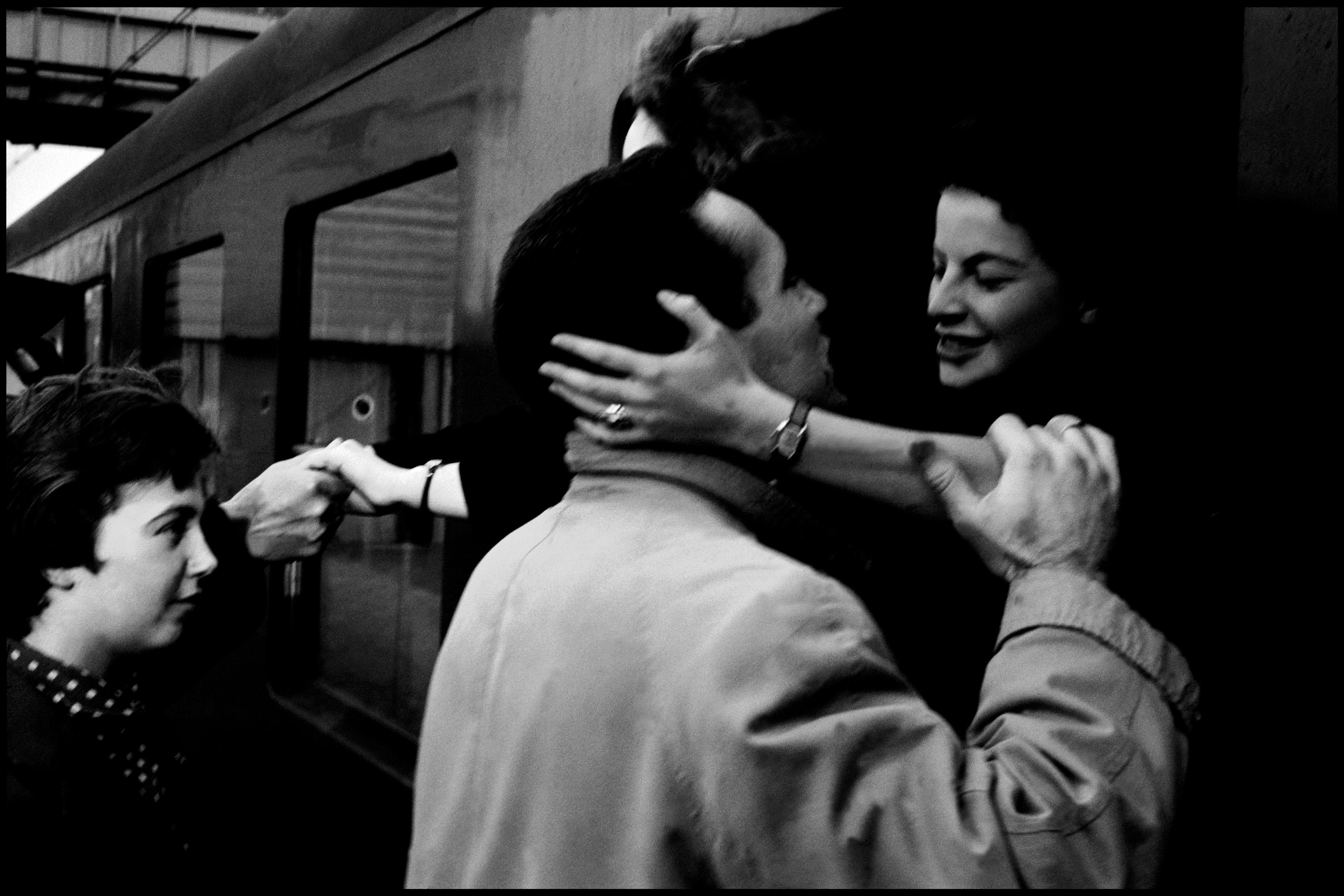

But not only do we need an awareness and feeling for the otherness of another, but also a willingness to lay ourselves open to their hurt. Sacrificing a relaxing evening with a film to call your friend and ask him how he’s doing is one thing. Attending to him in such a way as to make room for his grief, his neediness, his loneliness, is another. We are very quick these days to talk about relationships as toxic, of friends and relations as energy vampires. And, of course, attending to people in difficulties can be draining and sometimes more than we can manage. But a person who is truly understanding is willing to go to great lengths. That person is willing to be affected by and feel for another.

If we want to get better at being understanding, then, we need to do three things: attend lovingly and habitualise the neighbouring virtues of humility and vulnerability. We need humility to maintain a respectful attitude to the otherness of the other, and we need vulnerability to make sure we’re really open to whatever it is the other may be going through. If we join these in a disposition of loving attention, of patiently looking and listening, we should make progress.