On a late summer evening, as my wife and I ate dinner at home, three large crows lingered ominously in the front yard. We watched as a squirrel tried to chase them off, one by one, into the street. But they did not leave. The following afternoon, an intense, unexpected thunderstorm shook the house. A couple of hours later, my mother passed peacefully, her hand in mine, as we listened to a playlist of our favourite music and I reassured her we would all be OK in her absence.

I was wrong about that.

My mother’s death at 75 came sooner than expected, but it was not a surprise. Though pancreatic cancer is brutal, ugly and profoundly humiliating, it is not instant. Thankfully, her encounter with it was mercifully quick. Less than a year after her diagnosis, she was gone. A brief minuet with a murderer.

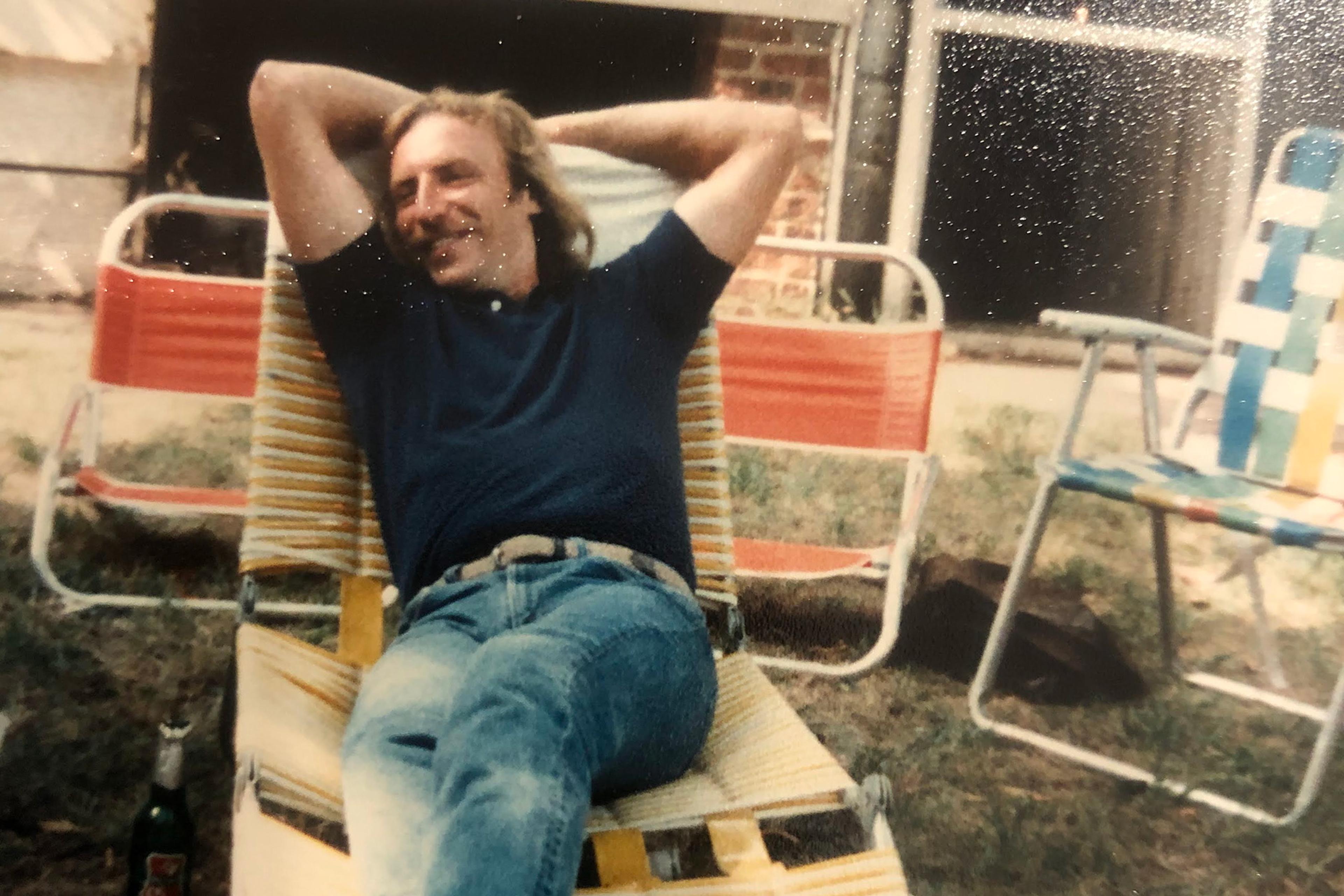

Her diagnosis seemed to materialise from nowhere at the end of 2017. She was remarkably fit and physically active for her age – she had even taken up skiing, albeit briefly, in her 60s. She was mentally sharp as well, and worked full time as a medical assistant in a Parkinson’s clinic, where she earned awards for the outstanding quality of care she provided her patients. Even though she lived in Seattle, on the opposite coast from our home in Connecticut, she was an active, doting, mischievous and proud grandmother to my son, with whom she developed a unique connection, despite seeing him infrequently. Then, without any sign or warning, she was facing death. It seemed impossible.

At first, we were hopeful. A visit to her doctor prompted by unusual, persistent abdominal pain led to early detection of the disease. Her case was atypical in a way that fostered hope in her prospects for survival, and an uncomplicated surgery to remove the cancer initially seemed to be successful. Subsequent tests, however, revealed the malignancy had already begun colonising her organs.

Without surrendering to resignation, we nevertheless started to prepare ourselves for the worst. Mom reduced her workload from full time to part time, but refused to retire until the demands of her job finally became too much. She took steps to ensure her will, life insurance policy and other vital documents were in order so that, if things did not work out, at least she would not be a burden to us at the end. When I was designated her power of attorney, our conversations about her end-of-life wishes became regular. She shared her worries about leaving my siblings and me, though each of us was already grown and established. I could tell she was also already beginning to miss her grandchildren, grieving the fact that she would not witness their proms, graduations, weddings and other milestones along their way to adulthood. As we talked about these concerns together, I began to consider how my grief would eventually take shape.

She decided that what time she had left would be better spent in the relative comfort of our home

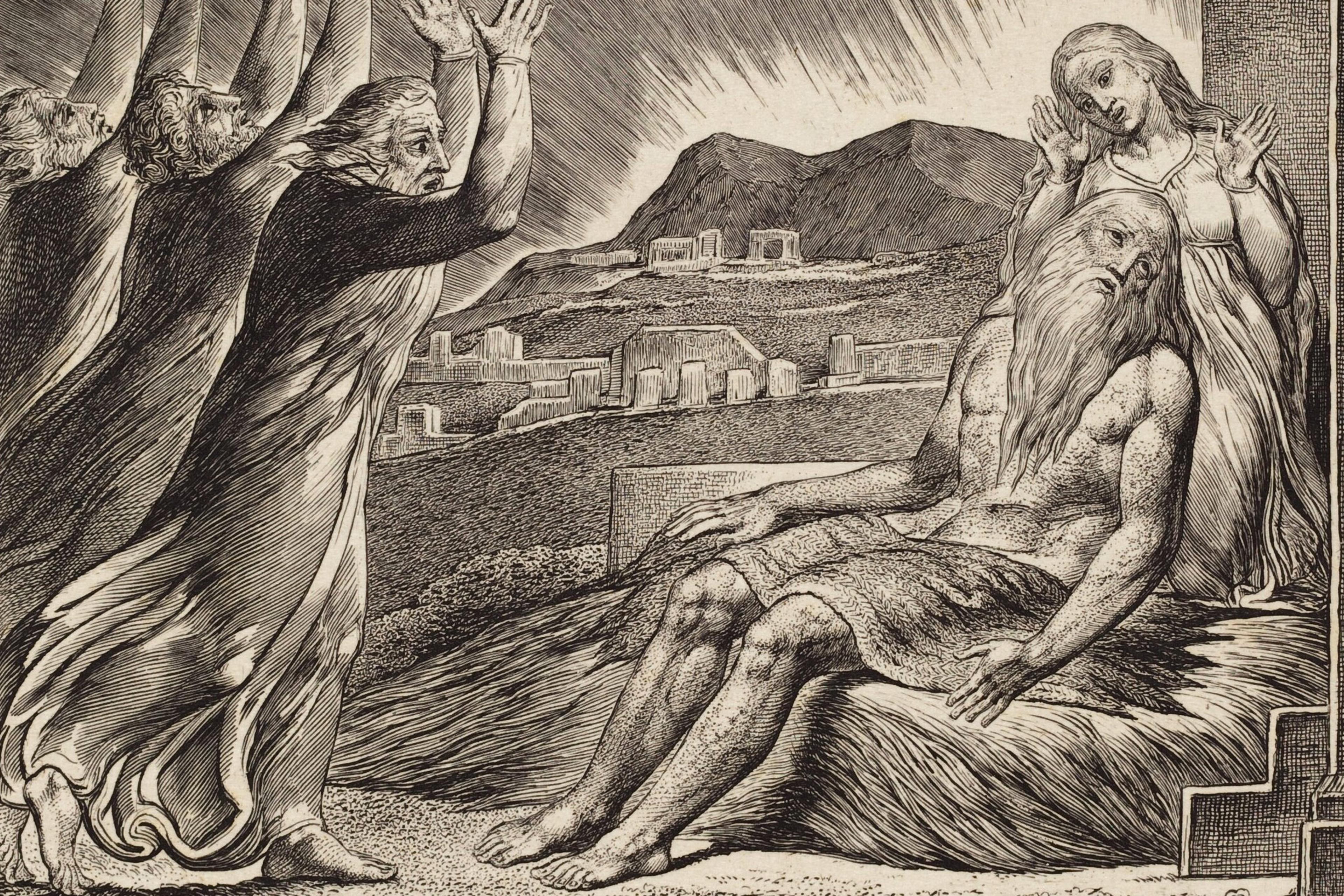

In her landmark work On Death and Dying (1969), Elisabeth Kübler-Ross laid out a five-stage schema describing the process of dying, which has become a widely accepted description of grief. Kübler-Ross’s ‘five stages’, grounded in hours of carefully conducted interviews with terminally ill patients, was no metaphor. Instead, it had the imprimatur of scientific research. No doubt you are familiar with the stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. Would this be the cartography of my coming pain, I wondered?

Soon, our shared fears became inescapable. Two separate chemo protocols failed. The inevitable became imminent.

As a last-ditch effort, mom’s oncologist recommended a clinical trial at a hospital in Connecticut, near our home on the other side of the country. In just a few short weeks, my brother coordinated the help of family and friends, and mom emptied out her apartment and relocated from Seattle to our guest bedroom. The first two weeks were a whirlwind. As if the steady schedule of visits to specialists and diagnosticians wasn’t draining enough on top of managing her daily care at home, a handful of sprints to the emergency department kept us continually on guard. My sister flew out from Seattle for a few days to help provide support, but we were in over our heads. Mom’s pain medication gave her horrific hallucinations, and at one point she left the house barefoot, believing she had seen my cousin lying murdered on the living room couch. We found her two blocks away, completely disoriented and blind with paranoia. The dog had escaped with her and was down the street in the other direction raising hell.

The day before she was due to begin the clinical trial, my mother decided to give up her place and receive hospice care instead. Her medical team had been clear that a best-case scenario would not mean a cure, but a little more time. She decided that what time she had left would be better spent in the relative comfort of our home, rather than suffering the rigours of the trial for what might well prove to be no payoff at all. Within a matter of days those menacing crows visited our lawn. She died the following afternoon.

A few months after she passed, after the family had grieved together and the sting of her death had dulled, I was preparing dinner and absentmindedly dropped a drinking glass. It glanced off the countertop, sending shrapnel to every obscure corner of the kitchen floor, and out into the dining room and side hall.

As I gathered the shattered glass from the floor, I found myself, inexplicably, beginning to cry. I was confused. What the hell was going on? The glass was ordinary, nothing special. We had a cabinet full of identical ones. It was hardly something worth crying about. And yet, I found myself setting the broom aside and surrendering to a fit of heavy sobbing.

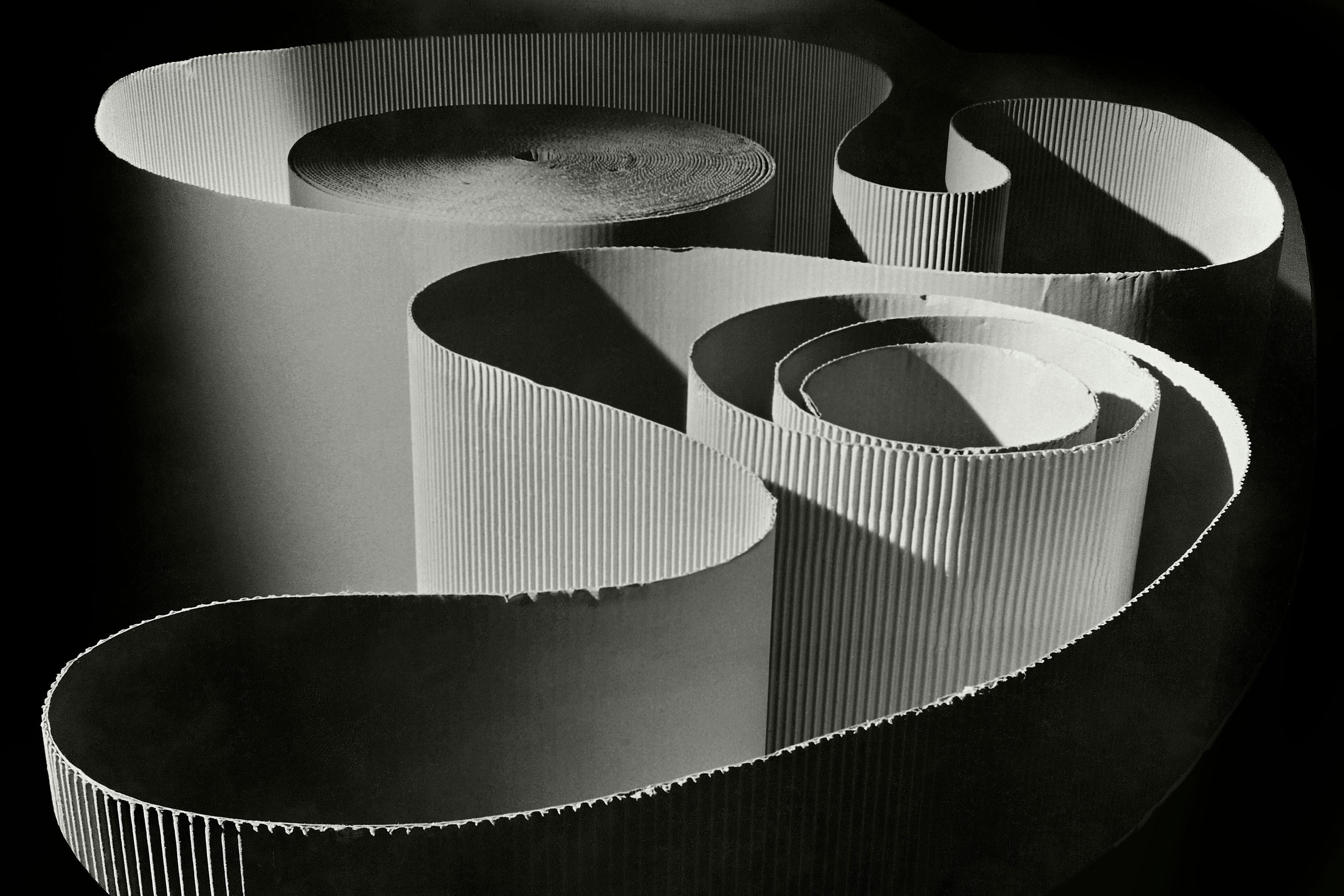

Like cleaning up broken glass, you move cautiously, so as not to get cut by the jagged edges of your grief

Puzzled and decentred by this bizarre flare of emotion, I redirected my attention to the task of cleaning the mess so I could resume cooking. A few minutes of focused effort and the broken glass was satisfactorily cleaned – ‘but not completely’, I thought to myself. Can you ever clean up broken glass completely? Spiky slivers that dashed across the countertop may be lurking unobserved, waiting to stab someone innocently setting down the mail or picking up their keys. Some may have shot across the floor, hiding under furniture or rugs. Some may have found their way into the food I was preparing. Was it safe to eat? How could I know? Tiny invisible razors could be anywhere. They could be everywhere. In fact, they probably were. As the thought crossed my mind, I considered: had my grief taken the same shape as the glass shards?

When you lose a loved one, a natural first impulse is to focus on managing the situation to contain the harm so that it doesn’t spill over into adjacent areas of life: work, casual friendships or the checkout line of the grocery store. Like cleaning up broken glass, you move cautiously, doing your best not to get cut by the jagged edges of your grief. You may start by focusing on ‘cleaning up’ the largest, most obvious pieces, the ones most easily handled and dealt with. Yet, at the same time, you understand all too well that the smaller, unobservable pieces are the real danger, and no matter how carefully and thoroughly you sweep the floor and wipe down the countertop, you will not find every last bit of glass. It’s only a matter of time before those scalpel-sharp remains gradually find their way into the open, undetected, and pierce you when you’re vulnerable and unsuspecting.

Grief is shattered glass.

Why did this idea resonate so deeply for me? Was it more helpful to explain my experience of grief through a metaphor than something more scientific, like the ‘stages’ described by Kübler-Ross? Metaphors, after all, are imaginatively colourful descriptions that stand in for literal accounts of the same thing. But metaphors have power. The American philosopher Richard Rorty argued that all language is metaphor. This might seem absurd. But Rorty claimed that language is fundamentally and unavoidably indirect. What we take to be literal is really made up of metaphors – indirect descriptions of our experience – whose usage has grown so widespread and common that we have forgotten they are metaphors. We mistake their literalness for directness, immediacy. But language always mediates. No matter how detailed, precise and specific, language is never the thing it describes.

This helps illuminate the paradoxical fact that metaphors often do a better job of conveying our experiences. If life has ever felt like an ‘emotional rollercoaster’, you understand this. When we deploy metaphors, we are intentionally, even if only intuitively, playing off the indirectness inherent in language. None of us can ever step inside the first-person experience of another’s grief to know it directly. But if I explained to you that my experience of grief is like shattered glass, I’ll wager you have a truer, more vivid sense of what I’m going through than if I simply told you ‘I’m grieving.’

What was there to deny? How does one bargain with cancer, anyway?

It may be tempting to think that a literal description of grief – for example, the five stages – describes my experience more accurately (and perhaps less colourfully) than the metaphor of shattered glass. The technical, detailed, even scientific descriptions typical of literal language often lull us into the misperception that we know just what there is to know about a particular thing, and thereby have it under control. By having the correct, literal description of the thing, we somehow have the thing itself. But this is not the case.

The language Kübler-Ross used to describe grief does not describe my grief. I was clear-eyed about my mother’s death. What was there to deny? How does one bargain with cancer, anyway? My grief wasn’t incapacitating. It wasn’t there at all. Until it was, out of nowhere, like shattered glass that escaped the broom, cutting me open and releasing intense sadness. Our descriptions ought to be in service of our experiences, not the other way around.

The five stages are as much a metaphor for grief as shattered glass, despite the common tendency to take them literally. For many people, this metaphor is effective for making sense of grief. For me, however, shattered glass is a more meaningful and helpful metaphor. It captures a profound insight well put by the philosopher Mariana Alessandri in her book Night Vision (2023): ‘Grief puts us in touch with a basic fact: surviving hurts.’

In the past few years, I’ve come to find an unlikely comfort in the metaphor of grief as shattered glass. That’s not to suggest that simply having the metaphor enables me to predict when pointy shards of grief will resurface, or to avoid the pain they inflict. I’m still no better at anticipating those moments, for the most part, and I certainly can’t dodge the heartache when they arrive. But on those occasions when grief does catch me unsuspecting, the metaphor is a helpful tool for processing what’s going on, for turning shock into recognition, for reflecting. It helps me navigate the often unexpected, almost-always inconvenient moments when the grief of my mother’s passing emerges from some dark corner to deliver another laceration. Sometimes, it’s a mere nick. Other times, it feels like I’ve been impaled, and carrying on requires much more than simply forcing down the lump in my throat into my abdomen.

Understanding grief as shattered glass reminds me to accept the sharp edges of being alive. It reminds me that grief is unique and that mine need not look like anyone else’s. It helps me accept that we can never completely clean up what breaks.