The 19th-century philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche had firsthand experience with fanaticism. In 1885, his sister Elisabeth married Bernhard Förster, a far-Right, antisemitic activist. Förster had achieved notoriety for co-authoring and promoting the ‘Antisemites’ Petition’ (1880), which demanded that Jewish people be denied civil rights, barred from civil service jobs and prevented from immigrating. But that petition wasn’t enough for him: he alienated even some of his most vitriolic associates when he concocted his plan to establish an Aryan colony in Paraguay. This colony, New (Nueva) Germania, would admit only those of demonstrated ‘racial purity’. It aimed to dominate and potentially enslave Paraguayans, who would serve the colonists. Its ultimate aim, as Förster put it, was to attain the ‘purification and rebirth of the human race’. It was an abysmal failure: though Förster set off with about 40 settlers, within two years half of them had died of malaria or starvation, and many of the others had returned to Germany. Faced with the collapse of his plans, Förster killed himself in 1889.

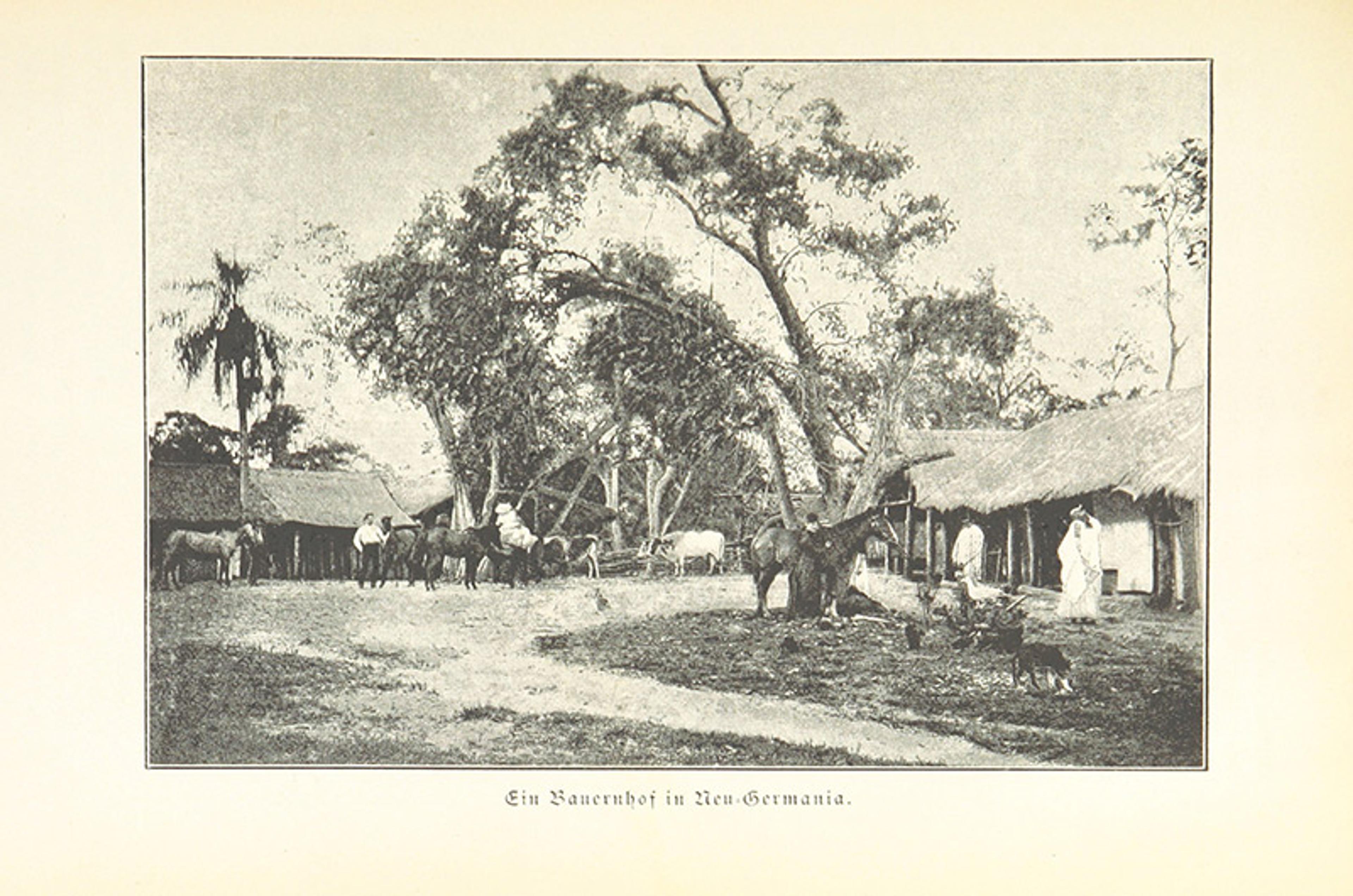

A farmhouse in New Germania, Paraguay, from Dr Bernhard Förster’s Kolonie Neu-Germania in Paraguay. Courtesy of the British Library/Flickr

Förster was a fanatic’s fanatic, too fanatical even for some of the most ardent antisemites. Nietzsche despised him, telling his sister that her marriage was ‘one of the greatest stupidities you have ever committed … Your association with an anti-Semitic chief expresses a foreignness to my whole way of life which fills me ever again with ire and melancholy.’ Förster was an ‘agitator’, a zealot whom Nietzsche saw as embodying so many traits that he deplored. Nietzsche wanted to avoid that kind of fanaticism at all costs. ‘You will not find a trace of fanaticism in my being,’ Nietzsche claimed.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Nietzsche offers us some of the sharpest philosophical insights into the origins and consequences of fanaticism – insights that remain as relevant in our modern social world as they were in his time. By engaging these ideas, we can better understand contemporary fanaticism and develop strategies to undermine it.

What exactly is fanaticism? There are three key features. First, fanaticism involves a passionate commitment to an identity or cause: the fanatic burns with a desire to realise his goal, despises those who oppose it, and experiences rapturous joy in the presence of like-minded others. Second, fanatics are dogmatically, stubbornly resistant to changing their minds; you’re not going to convince a fanatic to give up his cause by offering some reasonable objections or pointing out inconsistencies in his views. Finally, fanatics are willing to resort to extreme methods – violence, subversion, an upending of the social order – to secure their goals. In doing so, they often risk their own lives or the lives of others.

Of course, people can be devoted, dogmatic and extreme for all sorts of reasons; we may even recognise some of these tendencies in ourselves. So how do these commitments differ in the case of the fanatic? After all, a person can be a passionate political actor without being a fanatic. The person who devotes her life to combatting corruption, or battling racism, or preserving the environment need not be a fanatic. So it can’t just be the strength of a person’s commitment to a cause that determines whether they are fanatical. Something else must be at issue.

Fanaticism gives us a form of brittle strength that conceals a deeper weakness

Fanatics are certain, just like you or I might be certain about our most cherished values. But Nietzsche argued that, for the fanatic, this certainty is needy; it is a self-protective mechanism. This, too, is a tendency we may at times recognise in ourselves: the spouse might need to believe that his partner is faithful despite all the evidence to the contrary, while the failed actor might need to believe that she will someday succeed. Similarly, the fanatic needs to preserve her core commitment. Her conception of herself depends on taking her cause as fixed: because her identity is partly constituted by her unwavering devotion to her cause, questioning or abandoning her cause would be tantamount to questioning or abandoning her very identity. A person with a robust, secure sense of self can tolerate ambiguity, dissent and critique (even if she doesn’t change her commitments as a result); the fanatic can’t. As Nietzsche wrote: ‘Fanaticism is the only “strength of will” that even the weak and insecure can be brought to attain.’

It is this dogmatic resistance to the effects of reasoning, combined with deep-seated fragility, that makes fanaticism pathological. Fanaticism gives us a form of brittle strength that conceals a deeper weakness: this ‘strength’ can be maintained only by ignoring, suppressing or destroying any possible threats. Recognising any threat would lead to ‘crumbling and disintegration’, the fanatic needs to blind himself to ambiguity: ‘Not to see many things, not to be impartial in anything, to be party through and through, to view all values from a strict and necessary perspective – this alone is the condition under which such a man exists at all.’

Once we understand what fanaticism is, we’re in a better position to explain how it spreads – and how to fight against it. Nietzsche argues that certain kinds of narratives have great power: they can change us, transforming who we are. And if there’s one kind of narrative that’s perfect for generating fanatics, it’s the resentment narrative – a powerful story that encourages and nourishes the fanatic’s unique brand of brittle strength.

Resentment narratives paint a picture of life in which all of one’s problems and difficulties are traceable not to the rich ambiguity of the world, or to personal faults, but to simplistic, us-versus-them dichotomies. Their most basic form is this: you suffer because a group is unjustly harming you. The Proud Boy sees feminism and liberalism as destructive forces devastating men’s lives; the ISIS member believes that only an apocalyptic war with those who deny its teachings will correct the world’s faults. These narratives foster a totalising, negative orientation toward an outgroup. They instruct us to hate those designated as responsible for our problems. They vindicate us if we accept the narrative, absolving us of personal responsibility for our difficulties and failings by placing the blame squarely on an outgroup’s shoulders. Finally, they provide us with a readily achievable goal: to respond with hostility and aggression toward the oppressing outgroup. The driving philosophies of ISIS, Al-Qaeda, Stormfront and all stripes of white nationalism, as well as other fanatical groups, take the form of the resentment narrative.

By blocking the spread of resentment narratives, we might slow or prevent the spread of fanaticism

Resentment narratives are powerful because they are emotionally satisfying and identity providing. They offer emotional satisfaction by enabling fanatics to transform their feelings of powerlessness, disaffection and malaise into a seething, hate-filled resentment that can be channelled outwardly into aggressive reactions toward others. And they are identity-providing because they give the fanatic a way of defining herself, albeit in a negative way: what’s most important to the fanatic is what they reject, despise, or fear. The resentment narrative says: that outgroup is evil, and you can define yourself as not that.

This creates an enduring state of conflict that brooks no resolution. If your very identity and sense of self are bound up in your grievances – in your opposition to an outgroup – what would motivate you to address any problems with that outgroup in a genuine way? Eliminating the conflict would extinguish your sense of who you are. You would have to find new conflicts, new grievances, new battles. Your opposition thus becomes a fixed point, something that you cannot let go. Indeed, as political and social tides ebb and flow, fanatical groups – such as those we’ve noted – identify new threats, adapt their lists of grievances, and distinguish new enemies and perceived slights, ensuring that the conflict will continue unabated.

These powerful, damaging resentment narratives have nearly unlimited potential to spread and infect – especially today, when social media and internet communication make it so easy for disaffected individuals to find and latch on to them. But if resentment narratives create fanatics, they also provide an obvious checkpoint: by blocking the spread of such stories, we might slow or prevent the spread of fanaticism. That’s easier said than done, of course; these identity-providing, emotionally satisfying stories give us something to be and something to fight for. People who feel rootless, purposeless, without direction; people who are dissatisfied, disaffected, downcast; people who see their lives as full of failings; these people want more. They crave exactly what the resentment narrative provides: purpose, direction, stability, a vindicatory self-conception.

But Nietzsche offered us a way of battling against fanaticism, showing us how we can combat its spread and prevent the emergence of new fanatics. First, we can destabilise whichever resentment narratives arise in our culture. Alternatively, we can try to fight the conditions that make resentment narratives appealing in the first place.

Pursuing the first strategy, Nietzsche argued that because the resentment narratives lack a rational foundation, and draw power mainly from the ardency of their devotees, they can be weakened by a shift in the cultural current. He believed that ‘in the long run every one of these great teachers of a purpose was vanquished by laughter, reason, and nature.’ In other words, while fanatical narratives can’t be undermined solely by rational objections, they can be undermined when we combine rational objections with an attempt to make the narratives seem absurd, laughable, comic, and opposed to important parts of human nature (for example by showing that it conflicts with some of our central motivations or aspirations). Nietzsche believed that he could undermine fanatical aspects of Christianity in this way: he claimed that in the modern age ‘what is now decisive against Christianity is our taste, no longer our reason’. He hoped that such changes in taste could spread, disrupting fanaticism in all its variants.

The second strategy is more difficult, yet it is what Nietzsche most ardently yearned to achieve. Rather than trying to satisfy our craving for simplistic, totalising narratives and stable, unified identities, Nietzsche encouraged us to rid ourselves of those desires. He urged us to become free spirits – existentially flexible subjects who can devote ourselves to causes without rigidity, tolerating life’s uncertainties and frustrations, seeing ourselves as multiple, and finding grounds for self-affirmation. To do this, we would need to stop experiencing ambiguity and uncertainty as a threat; we would need to stop projecting our personal failings and dissatisfactions outward. The free spirit can ‘take leave of all faith and every wish for certainty, being practised in maintaining himself on insubstantial ropes and possibilities and dancing even near abysses.’ Tolerating danger, unthreatened by ambiguity, and able to maintain an affirmative self-conception without falling into simplistic dichotomies, the free spirit would not need to negate others in order to affirm herself. Nietzsche thought that he had pulled this off – and he hoped that we would follow him.