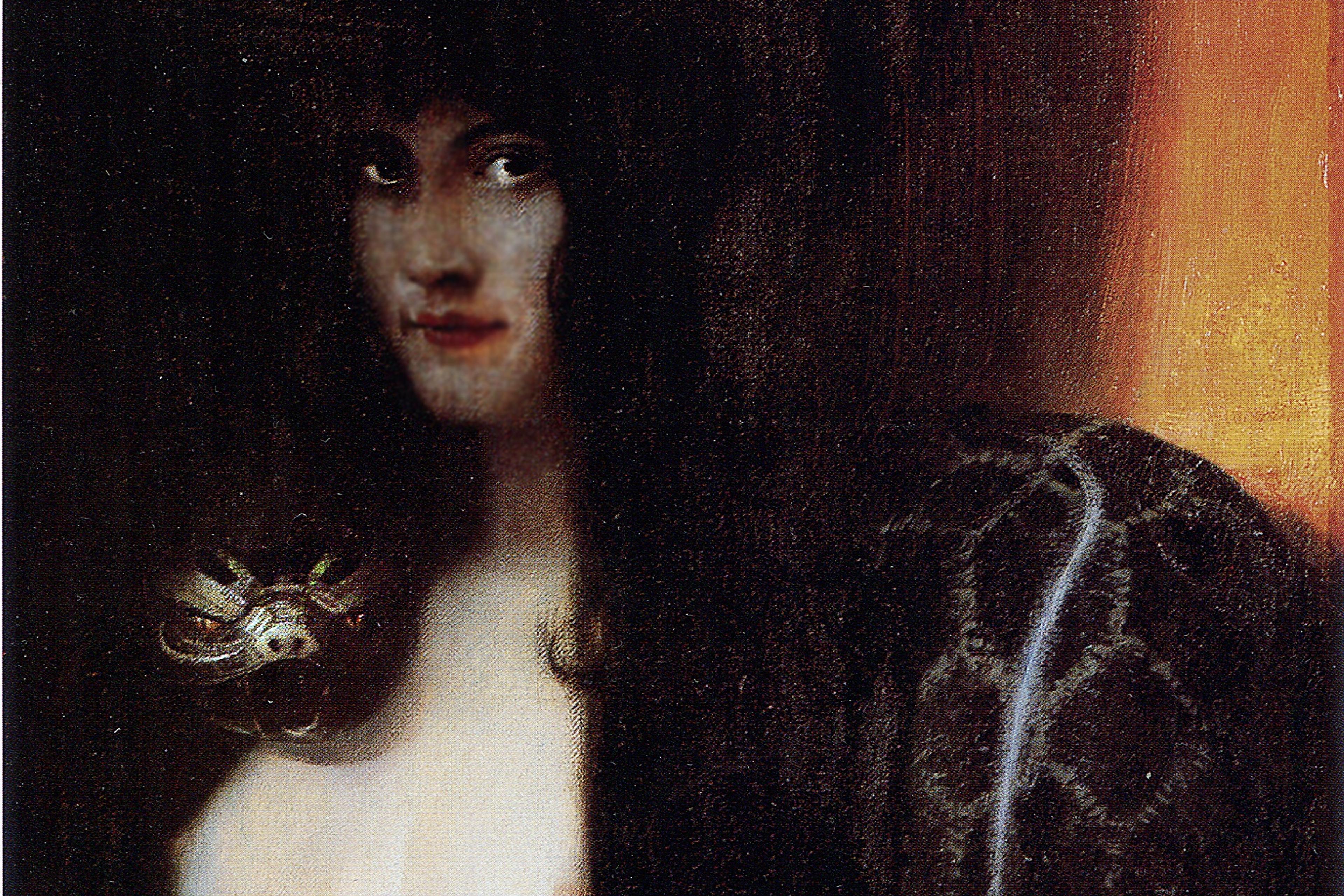

Costin Alamariu, likely the author behind the pseudonym ‘Bronze Age Pervert’, is a new addition to the long list of Right-wing political figures with misogynistic worldviews. ‘It took 100 years of women in public life for them to almost totally destroy a civilisation,’ he writes. To replace this gynocracy, he advocates for a ‘caste of men who would be able to guide society toward a morality of eugenics.’ Alamariu has also claimed philosophical credentials for this worldview. His work, disseminated in social media posts and the self-published book Bronze Age Mindset (2018), takes inspiration from a philosopher with his own reputation for misogyny: Friedrich Nietzsche. Nietzsche infamously longed for an Übermensch who would upend traditional morality and free the strong from its stifling limitations. This longing was sometimes paired with an apparent hatred for women who were holding men back, demanding that they be compassionate and domesticated rather than heedless and strong. This pairing seems to fit Alamariu’s views nicely, earning him the distinction of representing the ‘Nietzschean fringe’ of conservative extremists.

Nietzsche’s misogynistic reputation is nothing new: it was well established and debated in his lifetime. This did not stop one very intelligent woman from taking up the Nietzschean cause and doing so, ironically, in the name of women’s empowerment. Her embrace of Nietzsche made her one of the most powerful German feminists of her generation. It also allowed her to enable Nietzsche and this deplorable vision of the triumph of the strong.

Helene Stöcker photographed in 1930. Courtesy the NYPL Digital Collections

Helene Stöcker was born in 1869 into the suffocating strictures of German bourgeois respectability. After chafing against religious and cultural limitations as a teenager, she discovered Nietzsche at the age of 21. ‘From this moment forward … my interest, my joy, my enrichment through Nietzsche … has never ceased,’ she wrote decades later (all translations of Stöcker are by Lydia Moland). ‘To no other mortal spirit do I feel myself so deeply bound.’ In Nietzsche she found caustic contempt for outdated norms, a vision for a humanity emancipated from tradition, and an exhortation to be oneself, whatever the cost. ‘I owe him my particular gratitude that he has freed us from dogmatism and legalism, that he has allowed those who live from his great wealth the inner freedom of the development of their being,’ she wrote. In 1901, Stöcker defended her dissertation on philosophical aesthetics, making her one of the first German women to receive a doctorate. In lectures and essays, she began promoting Nietzsche’s thought, helping catapult him from the disgraced margins of academia to the central place in the philosophical canon he now enjoys.

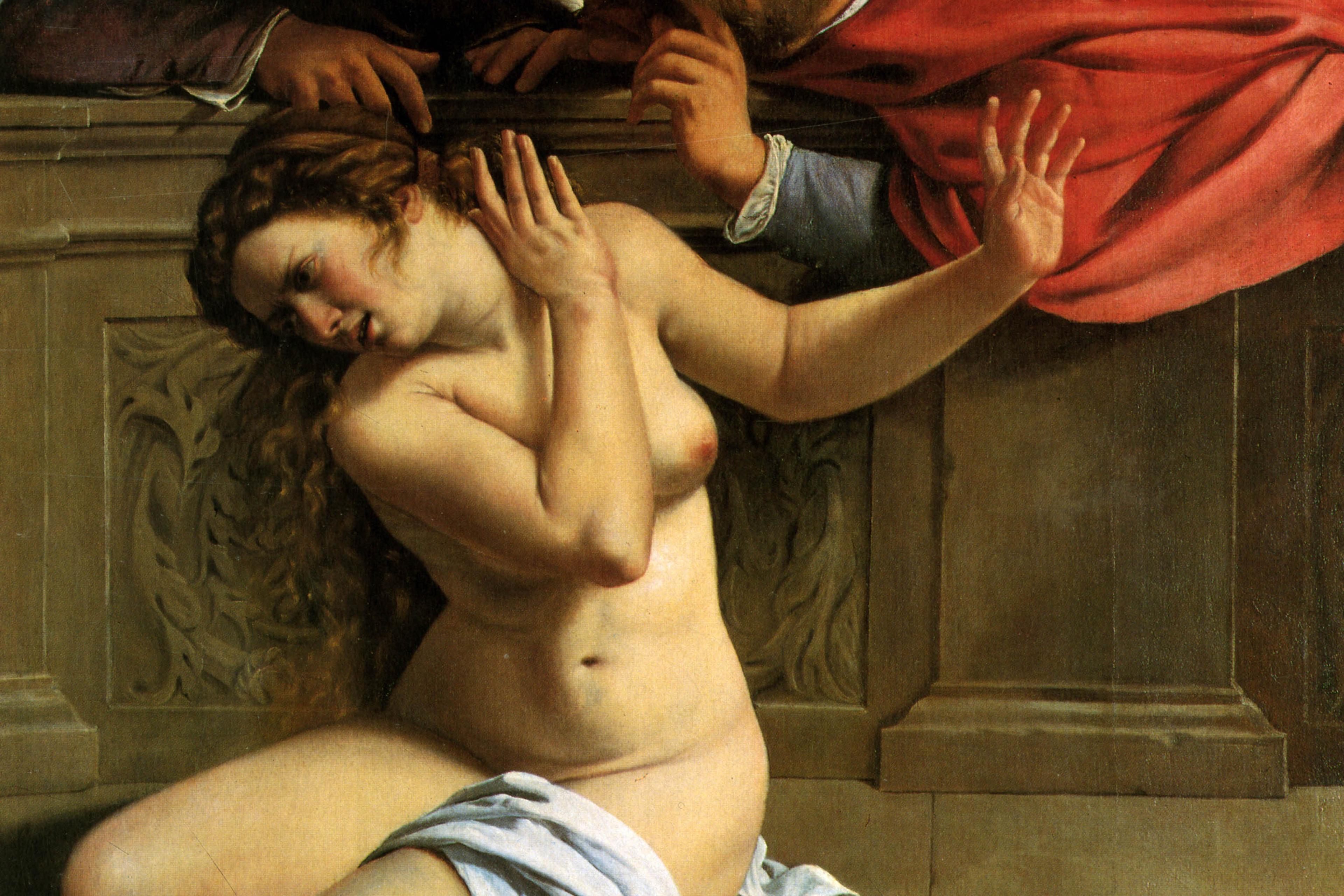

Nietzsche’s misogyny presented a problem. In On the Genealogy of Morals (1887) and other works, he envisioned a society of elites uninhibited by sympathy for the weak, unfettered by conventional ties. And what were women, in the society Nietzsche and Stöcker inhabited, but the weak? Wasn’t their demand for men’s devotion and decorum a stifling impediment to men’s natural strength? Didn’t their need for protection hamper the ‘will to power’ that was the only thing, according to Nietzsche, that could rescue humans from their own decay?

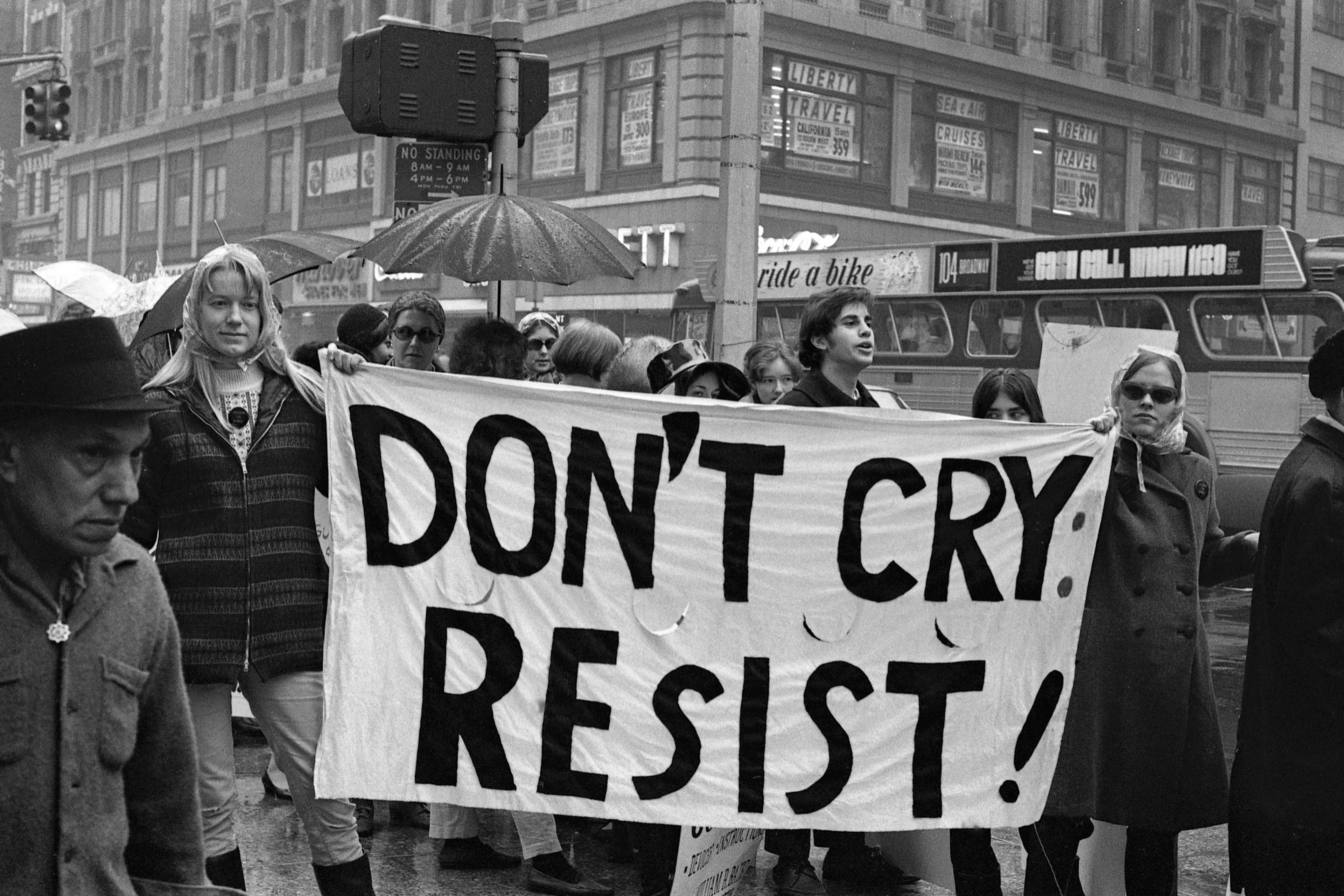

Stöcker seems never to have doubted that she could claim Nietzsche’s vision of freedom for herself and for all women. As early as 1892, she began using Nietzsche to argue that tearing down society’s restrictions would allow women to become free and powerful. She credited him with destroying the ascetic morals that claimed to find ‘something debased and impure’ in women. She praised his hatred of meekness and complacency, exhorting her readers that ‘the time is ripe for a fresh, joyful struggle.’ In place of conventional restrictions, Stöcker envisioned a ‘New Ethic’ of strength and joy. This New Ethic promised nothing less than a ‘new humanity – men and women – Nietzsche’s higher humans, who are permitted to say yes to life and to themselves,’ she wrote. ‘That the time has come also for women to become more conscious of this highest happiness which humans alone are worthy of, is my unshakeable belief.’ She knew this was audacious. ‘You say we demand too much?’ she challenged her readers. ‘Oh, we’re not demanding it,’ she assured them. ‘We are taking it for ourselves – the only sensible method of legitimation in the world.’

Stöcker argued that only in fully realised love could women reach their Nietzschean potential

Still, Nietzsche’s contempt for women was an embarrassment. Stöcker addressed the problem head on. In a 1901 essay entitled ‘Nietzsche’s Misogyny’, she admits that he often railed against women, especially intelligent ones, and threatened to bring a whip when he paid them a visit. But only a fool, she claims, could fail to see that Nietzsche meant this ironically. She acknowledges that Nietzsche defined men’s happiness as pure willing and women’s happiness, by contrast, as subjugating themselves to men’s will. She insists, however, that this is true only of the women deformed by the corrupt society that Nietzsche deplored. She points to passages where Nietzsche imagines ‘noble, free-minded’ women who ‘strive for the elevation of their gender.’ She assures herself that Nietzsche ‘spoke such earnest, wonderful words about women … that we might call ourselves happy, if all men were such enemies of women.’ With her exoneration of Nietzsche’s reputation complete, Stöcker returned to articulating Nietzsche’s ‘religion of joy … that transforms everything earthly into engoldened [and] divine’ and to breathless speculation about ‘what kind of humans will thus be made possible!’

In pursuit of this intoxicating potential, Stöcker did what seems to be the least Nietzschean thing possible: she went to work helping the weak. She became one of her generation’s leading feminists, dedicating her life to eradicating the wretched conditions that kept women needy and dependent. She fought for access to abortion, paid maternity leave, and legal protection for single mothers. She published powerful objections to norms that allowed men to visit prostitutes but demanded chastity of women, then ostracised women for the sexually transmitted diseases they contracted from their husbands. She became an internationally known lecturer, using her vision of liberated womanhood to argue for better working conditions for women as well as their access to higher education. To the horror of her more conservative allies, Stöcker also advocated for sexual freedom and fulfilment, arguing that only in fully realised love – physical as well as spiritual – could women reach their Nietzschean potential. She helped found the League for the Protection of Mothers and Sexual Reform and edited journals expressing the society’s views. In one article after another, she argued that women should be allowed to choose when and with whom to have children and should be provided with health care that would allow children to thrive. ‘Followers of New Ethics demand that every German mother should be able to nourish her own child,’ she wrote. To that end, she added, ‘there must be basic legal conditions’ for women’s flourishing.

Despite Stöcker’s progressive feminism, her worldview was infected by a darker Nietzschean theme that is also echoed in Alamariu’s writings. Stöcker was part of the ‘social-radical’ wing of the eugenics movement: a group that included feminists who wanted to ensure that women could have healthy, ‘normal’ children. This, too, was part of the idea of a Nietzschean ‘new humanity’ that would be free from illness and deformity. Stöcker did not explicitly advocate for forced sterilisation or euthanasia. She was not, to my knowledge, a racial eugenicist. But she gave space in her journal to others who were, and she herself suggested that ‘society should prevent conception’ among those with hereditary illnesses. In a world created by her New Ethic, she also imagined it would be necessary ‘to find means of preventing the incurably ill or degenerate from reproducing.’ Stöcker’s use of Nietzschean terms later appropriated by the Nazis, such as Übermensch and Weltanschauung, has also tainted her reputation. Her lifelong friendship with Nietzsche’s sister, the Aryan nationalist Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, should also give us serious pause.

Some Nietzsche scholars will be quick to respond that all this is unfair to Nietzsche. But Nietzsche often gets a free pass. Philosophers I admire write movingly about how Nietzsche can help you achieve self-fulfilment, cope with depression, or be a better collaborator at work. Nietzsche so portrayed can seem like nothing more than a friendly self-help coach, encouraging you to be true to yourself, whatever your boss or partner or society says. It’s true that this kind of inspiration can be found in Nietzsche. It’s also true that the philosophical canon would be poorer for his absence. We must, however, also acknowledge that his philosophy provides fertile ground for the kind of authoritarian hero-worship Alamariu represents and that far-Right conservative activists and bloggers are actively spreading to a growing audience.

Her international reputation as a feminist meant that she knew her arrest was imminent

As part of his analysis of Alamariu and his place among Right-wing intellectuals in The New York Times, the journalist Damon Linker cautions that ‘[i]t’s hard to know how seriously to take all of this.’ Alamariu is apparently sometimes deliberately cartoonish and ironic, breaking the rules of argument just as he wants to break the social order. This, too, he might have learned from Nietzsche, whose mix of mythology, irony and levity has endeared him to legions of undergraduates – especially, in my experience, male undergraduates.

Stöcker herself, it is important to note, did not take the risks evident in Nietzsche’s vision of elitist hegemony seriously enough. As she continued to work for women’s liberation after the First World War, German fascists began using Nietzsche to argue for a ‘postliberal’ age. They named ‘natural aristocrats’ like Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler Nietzsche’s ‘spiritual descendants’. Alfred Bäumler, the Third Reich’s official Nietzsche scholar and a professor of philosophy in Berlin, began to advocate for what Steven Aschheim describes as a Nietzschean ‘reassertion of warlike, heroic male values and community’. This kind of argument made Stöcker, who had dared to apply Nietzsche’s liberationist philosophy to women, a pariah. Her international reputation as a feminist meant that when the Nazis came to power in 1933, she knew her arrest was imminent. From one day to the next, she fled: first to Switzerland, then to England, then to Sweden. As Nazi armies drew ever closer, she finally took the Trans-Siberian Railway across Russia and a steamship from Japan to San Francisco. After a decade of exile, she died an impoverished refugee in New York City. An ocean away, Nietzsche-inspired elites continued to pursue a version of ‘new humanity’ that almost destroyed a civilisation: not within 100 years, as Alamariu’s accusation against women’s power alleges, but within the last short decade of Helene Stöcker’s passionate, Nietzsche-inspired life.