Pools open portals. All bodies of water issue invitations, but there’s a special doorway provided by a familiar concrete rectangle, usually 25 or 50 metres long, filled with warm water. In that unnatural geometry, human bodies are buoyed up by blue-green chlorinated translucence. Solid black lines coat the out-of-reach bottom. Splash-dampening floats outline the lanes. Like other bodies of water, swimming pools structure human movement. But pools are friendlier than most wet spaces. These boxes – isolated from crashing waves, surging swells or freezing temperatures – are places constructed for swimming alone, for its stroke-by-stroke practice. They are good environments for thinking, too.

Swimming is my pastime and practice, my habit and meditation. I swim to think, to work my body, and to contemplate the place of humans in alien surroundings. I swim to practise keeping afloat in an ever-wetter world. I swim with words, too, accompanied and kept in time by poets and water-writers whose obsessions limn my own. Truths that arrive during immersion sometimes take shape in words, formed through the rhythm of arms and legs. But, as often as not, the water that envelopes me carries me to places I had not known I wanted to go.

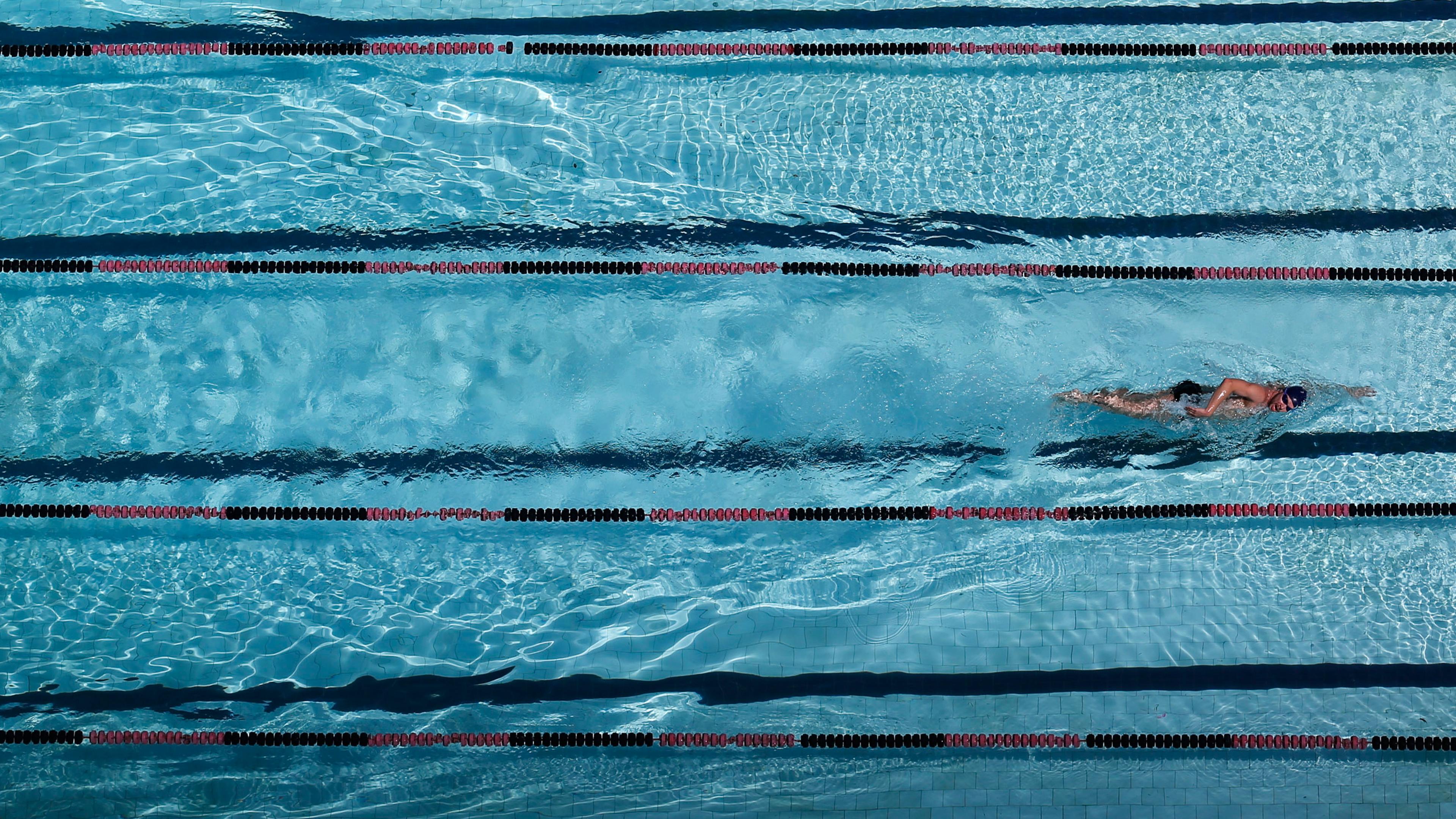

I recently paid a visit to perhaps my favourite portal of artificial water, the 50-metre outdoor pool at the Palm Springs Swim Center in the California desert. Having avoided the crowds and poor ventilation of indoor pool-swimming for two years through the COVID-19 pandemic, I walked one early morning toward the rectangle of shimmering water as if it promised me something, as if I’d find answers there. I’d managed to reserve a private lane via a confusing online system designed for the pandemic era, which involved registering my identity with the State of California. Alongside my individual strip of water stretched another 20 or so lanes, many filled with swimmers. In the distance hung the steep vertical wedge of the San Jacinto mountains, capped with snow in early spring. The desert air pinched my skin with cold but the water, heated to a comfortable 20 degrees Celsius, welcomed my body.

I cleaned my goggles with non-fogging spit, slid into the warmth, dropped my face under, and pushed out, thinking about what I like thinking about most: feeling and form. I like thinking about these things on land, but something special happens during a swim. I recognise the tangible sensations of water on working skin, and feel each feeling as it passes over and around my flesh. I observe myself turning feeling into form.

I’m a practised swimmer, though by no means a champion. I’m neither Aquaman nor Lynne Cox, and I don’t slice through water like a dolphin. But usually I can slide my exertions into a form that’s efficient enough to provide a taste of smoothness. I swim accommodatingly, matching terrestrial body to alien environment. I attend to how the water feels, and I form my strokes in repeated efforts to bring unlike things – a human body, chlorinated water, desert air, a view of snow – into temporary harmony. These physical patterns also shape my thoughts into order, usually. An integration of body, mind and water was what I was seeking, stroke by stroke.

Mechanics should be the easy part.

Settling into rhythm, I reach my right arm forward to cup the water. As my arm extends, my torso twists, angling my weight over my ribcage, which rolls itself into alignment with the black line on the bottom of the pool. In this way, I fashion myself into a trim boat, parting the water on both sides, gliding over the ribs of the right half of my torso. Pulling the water back and in toward my chest with my right arm, I let my weight roll down off that supporting rib and slough onto my stomach. Reaching now with my left arm, my torso angles opposite-ways to stretch and ease my body up onto the other ribcage. Stretch, pull, roll, repeat. The pattern continues, with my face turning across my direction of travel to gulp air on every third stroke. Like twin canoes or hidden outriggers, my lungs form themselves into momentary pontoons inside their rib-frames. First one side, then the other.

Many long-distance swimmers have individual mnemonics to keep in form. The marathon swimmer Diana Nyad has tried subvocalising the Beatles songbook, but prefers the constant rhythms of ‘Frère Jacques’ and ‘Row, Row, Row Your Boat’. I’ve got a less catchy tune in my head this morning, a jumble of obsession from the 17th-century English broadside writer Richard Younge, who imagined himself, in 1636, as consubstantial with a sailing ship:

My Body is the Hull; the Keele my Back; my Neck the Stem; the Sides are my Ribbes; the Beames my Bones; my flesh the plankes …

In the water, I begin to unlearn habits of dominion and fantasies of control

Younge’s glorious fantasia goes on for a full printed page, mixing human body parts, Christian souls and nautical terms. I don’t have the whole page memorised, but the two-beat pattern of the first half-dozen parts – my body, my back, my neck, my ribs, my bones, my flesh – carries me through the water. I swim into Younge’s imagined unity. I seek to form myself hydrodynamically, to surge through water with practised exertion, to feel the fluid moving against me and know that it is my own flesh and bones, ribs and neck, back and body moving forward. I don’t want to be on a ship but to move ship-like. And I want to recall that the water is always moving too, even in the contained space of a concrete pool. It’s all in motion, sloshing, shifting, moving, and moved – an unsteady portal inside which I come to feel my body in the form of a ship.

Sometimes, I use the portal to swim-think with Hamlet, who calls his body a machine, and other times with Emily Dickinson or Joseph Conrad. Today, I seek Younge’s mad company. To be a ship-body, all its parts and entanglements, moving through a moving fluid. Falling back into that form isn’t like coming home because there’s no home for land mammals in water. Instead, it’s like carving out slight continuities within changes, balancing in an unsteady space, feeling an uneven push of stability inside disequilibrium.

In the water, I begin to unlearn habits of dominion and fantasies of control – it’s about not-knowing and feeling out of place. It’s never about mastery. That’s what I love about swimming. In the water, I’m always partially enabled, never certain, always at risk. If meditation requires an exploration of impermanence, swimming-meditation activates transience on the skin. Its embodied teaching flashes me into a fragile, tangible, barely hopeful body. It’s the best way I know to understand being a physical form in an unstable world.

That’s the way it started, as I pushed off in the Palm Springs desert, but not the way it went. Maybe 20 minutes in, having settled into a slow sloshing rhythm, something gurgled up inside to unsettle me. Sea sickness feels familiar to anyone who’s spent time with boats, and I’ve felt its wiry green tendrils grip my swimming bowels before, especially in choppy water. I’d never felt it so strongly in a pool, but there it was, wrenching my stomach in its tightening vice. I recalled, too late, the old rule about not eating before swimming. That’s the thing about portals, you’re sometimes different once you’ve entered them.

Swimming surfaces the biggest questions. How can our bodies endure immersion? What recourse can we fashion for ourselves when we feel sick, impaired or unable? How will an increasingly watery environment, an age of rising seas and torrential storms, shape or break human ideas of order? Once we’re forced into the transformations of high water, can we keep swimming and surviving?

I didn’t want to pull an Aeneas in a pool full of winter-tanned Californians

I mulled my nausea while struggling to stay in form and in motion. Is this, I wondered, the universal response of land-mammals to water? My strokes grew asymmetrical. I needed help. I turned to my primary personal flotation device: poetry.

Seeking connection, I clutched at David Hadbawnik’s new version of Virgil’s Aeneid, which features the hero retching over the side of a ship:

Aeneas gets scared.

Limbs loosened in fear, he

groans, bends over and

pukes over the boat’s

edge.

I didn’t want to pull an Aeneas in a pool full of winter-tanned Californians. But my body recognised the nausea of the hero who was forced into an imperial dream that he didn’t really want. I kept swimming. I felt dragged down by the cannonball in my belly, pulling me deeper and lurching from side to side. I struggled to keep my strokes even. My rib-to-rib oscillation scattered. My thoughts lost coherence.

I cut my swim short and walked unsteadily to my car.

The door to the Palm Springs Swim Center opened early for me the next day. My bare feet burned from the touch of cold concrete as I walked across the deck to the glowing rectangle. Morning light cast geometric shadows down the faces of the San Jacintos.

After the second swim, I returned to my car on steadier feet, and left the desert feeling that I’d swum-thought my way into something new about feeling and form. The poets always arrive before us. Walking back to the car, I repurposed T S Eliot’s line about how ‘human kind cannot bear very much reality’; water seemed to me to displace reality: Human bodies cannot bear very much fluidity. No matter how much I love water, how I crave its embrace, seek its touch, my terrestrial body cannot bear very much immersion.

Though I did not puke over the boat’s rail, the pool’s portal churned me more than I had expected. Two end-of-winter days under dry desert air reminded me that pools are little oceans, that even human-designed rectangles can wrench my body from its rhythms. Once through the door, bodies change, and thoughts change. But absolute transformations? They hover beyond my grasp as I stretch, pull, roll, repeat. In the pool I find new alignments – water as warm embrace, the thin taste of cold dry air, solid daggers of snow on the peaks – and disarray, too. In that rectangle of light, I feel the weakness of my body, its partial abilities, a baseline of risk. Swimming’s an inadequate response to the Earth’s watery future. Do we, I wonder, have the forms, and practices, to face what’s coming?

Back home, on land, I find myself thinking about the feeling of immersion, visualising the form that enables me to endure it, and silently vocalising the words to an impossible dream: ‘My body is the hull; the Keele my Back; my Neck the Stem; the Sides are my Ribbes; the Beames my Bones; my flesh the plankes …’