Last summer, just after turning 50, I gave myself a kind of permission I’d never granted before. I rented a small cottage by a lake in southern Finland, moved in with my dog for nearly four months, and lit the wood-fired sauna each evening. Then I stepped into the heat, followed by the cool embrace of the lake, only to return to warmth again. It was the first time in more than 30 years that I spent an entire season in the country where I was born.

The first sauna I remember was in the basement of an apartment building in a small Finnish town, where my parents lived when I was about three. Every Saturday evening, each household had its own hour. Later, we moved to a single-dwelling house and, as a teenager, I began to sauna alone, experimenting with the heat, steam and duration. Sometimes, I would let the fire almost die out, then throw a bucket of water onto the rocks, filling up the room with excessive steam. I was developing my own bathing style, and the practice gave me space to unwind through the turbulent years of growing up.

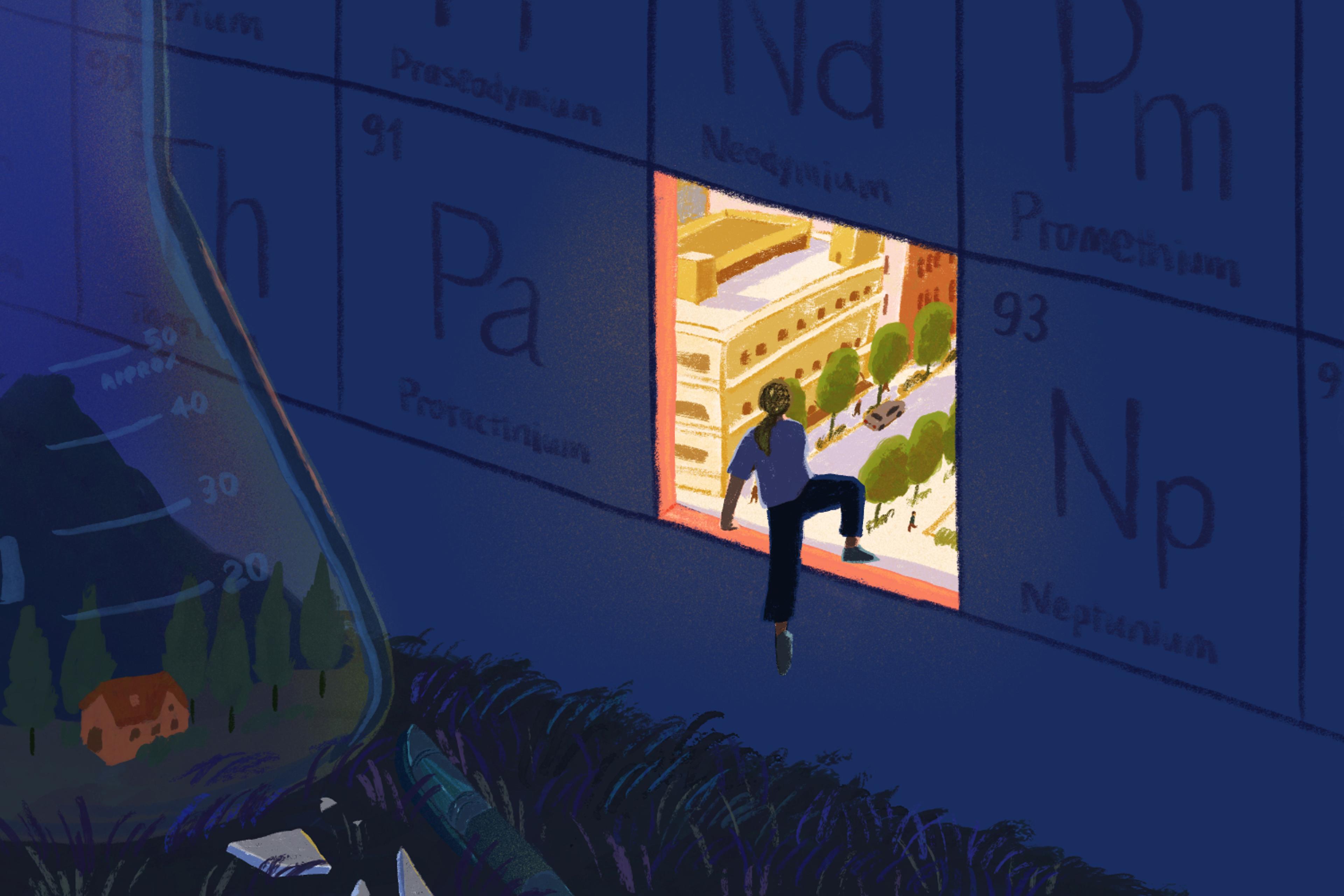

While my mother did her best to support me, I felt compelled to live on my own terms: at 20, I left Finland for the United States on an athletic scholarship. I trained for the heptathlon while studying psychology and sociology, and stayed on for graduate school, eventually earning a PhD in anthropology and settling in Canada. Through all those years in North America, my body craved the heat I had once known so intimately. I sought out saunas wherever I could – at hotels or university recreational centres. Usually, they came with an instruction posted near the electric heater: Do not throw water on the rocks. That felt senseless to me: without the steam the room felt like a hot box.

That’s because in Finnish, löyly is what happens when you throw water onto the hot rocks – there’s no such thing as ‘dry sauna’ in our tradition. Löyly envelopes your naked skin with steam. The steam may be biochemically identical to kettle vapour, but the experience is entirely different. This is what the anthropologist Paul Friedrich called linguaculture: shared experiences so fundamental they earn their own word.

In Finland, there are three main types of steam sauna: electric, wood-heated, and smoky. I’d used them all growing up, with wood-heated saunas like the one at my cottage the most common. Only on special occasions, like New Year’s at my uncle’s house, did I enter a savusauna, an ancient smoke sauna with no chimney. These are built around massive stoves and fired only before bathing; thick smoke fills the room and is ventilated before anyone enters.

The savusauna holds special meaning for my family: just a few years after the Second World War, my mother was born in one. This was intentional. At the time, the sauna was one of the few places warm, clean and private enough for birthing. In a way, my bodily inheritance – my epigenetic grammar – was shaped in sauna. And perhaps a little by smoke, too, but always with intermittent steam rising from the rocks, gently hissing its own stories, sometimes called the spirit of the löyly (löylynhenki).

A few years ago, my mother was diagnosed with cancer. I began visiting more often. Being by her side during emergencies became easier. Emotionally, I fluctuated between duty and compassion, trying to grasp what the English word ‘grace’ might really mean.

Human bodies, too, are shaped by the ecologies they inhabit

At 50, I gave myself time and space. Several months at a cottage with my dog. No plan. Just nature’s rhythm. In the wake of career burnout and the end of a long-term relationship, I needed to recalibrate. I’d lie on a linen towel Mom found at a thrift store, feet propped against the wooden wall, letting the heat soak in. Then I’d walk barefoot over moss to swim while my dog watched from the dock. It felt like washing off layers of stress that had settled too deep.

Anthropologists speak of sense of place – attachment to a landscape shaped by memory and ecology. In French, there’s a related term: terroir, or the taste of a place. It’s about how soil, climate and tradition shape a wine, or a life. Human bodies, too, are shaped by the ecologies they inhabit. As infants, we absorb microbes, nutrients and natural cues. They become part of our embodied archive, located in a bioregion, not just a nation-state.

As an anthropologist who studies kinship and migration, I know not to romanticise returns. Human history overflows with forced displacement, cyclical migrations and shifting borders. There is no absolute rootedness. And yet connections to place remain powerful. We each carry a geography of longing: places we leave, return to or never want to abandon over the course of a lifetime. That’s ontogeny. As a species, we trace back to Africa. That’s phylogeny. But origin isn’t home.

Some of my earliest memories are of sitting on sun-warmed rocks in the forest, barely able to walk, while my mother and aunts picked wild berries. I gathered birch twigs, pretending to have a sauna, summoning imaginary steam. Those were early scripts of the embodied grammar I was only now relearning. The syntax was simple: work hard to forage, then sauna to ease insect bites with heat and cold.

Food is one way terroir enters the body. Imported cornflakes mean nothing here. But when I pick wild bilberries, gather chanterelles, or catch perch from the lake for lunch, I enter a dialogue with the mineral profile, the microbes and the seasons of the place.

Each cycle of heat and cold was like a sentence, a punctuation mark, sorting out my anxiety

At the start of the summer, I feasted on wild strawberries during my morning runs – stopping to eat while watching butterflies. Every few weeks, something new to forage: lingonberries, wild cranberries, raspberries. In the fall, the woods filled with mushrooms – edible, poisonous, bitter. I didn’t need a guidebook to sort them. The knowledge came down to me through generations, and the lessons of kin.

As the weeks passed, sauna became a daily grammar – a ritual through which my body began to speak again. Each cycle of heat and cold was like a sentence, a punctuation mark, sorting out my anxiety. I wasn’t returning to the past. I was being translated into a different mode of being. One that is less linear and more cyclical, attuned to seasonal rhythms and environmental cues. This wasn’t about becoming Finnish again, or reclaiming some idealised origin. Rather, I was aligning with the pace of this place – the land, the air, the water, the stone, even with family.

In early August, after several hours of mushroom harvesting in the nearby woods, scratched and full of bug bites, I again heated the sauna. Then, as I stepped into the icy water of the lake, my body still glowing from heat, time slowed. I swam out while suspended between two worlds: the warmth of fire and the slight unease of the dark, cool water. Mist rose on the horizon. For a moment, I was no longer a bounded individual. I was a node in a web of land, memory, body and breath. Disoriented. And finally clear. This is who I am. This is where I belong.

There’s uncertainty in the air, in Finland and elsewhere. The war might spread. The economy may not recover. Maybe human progress has peaked – and was never equally shared. In times like these, many of us turn to consumption for comfort: buying, scrolling, seeking quick relief. I’ve done plenty of that myself. But by spending that summer at the cottage, I found something more grounded. A way of living not about acquiring or advancing, but sustaining. I began to re-root myself in the webs of land and kinship I’d once left behind to become myself.

Chopping wood, carrying water, lighting a fire – these acts reveal my future: I would move back to Finland. I know the price of summer here is a long, dark, bitter winter while I’ve grown used to the grandeur of the Canadian Rockies, where winters, though cold, remain surprisingly bright. Finland’s dark season will be harder. Still, when I step into the sauna, I return to something shared – warmth carried across generations, through war and peace, silence and song.

For me, this time in nature was a gift: space to listen, slow down, feel where the current pulls

And now, I share that space with my mother. I’m learning to see her as a full person, not just ‘Mom’. Sometimes I call her by name.

There’s a lot to learn, and to unlearn, and an overseas move is daunting. I sometimes find speaking Finnish awkward – there is no word for ‘excuse’ in Finnish – and I worry I can’t express all parts of myself I’ve cultivated through English. I know that small talk is superficial but it can also be a lovely way to connect in Canada, while in Finland the default tends toward silence.

Despite the worries, my direction feels clear – though much remains in the liminal. A friend tells me: as long as one isn’t running from but moving towards, things tend to work out. It’s difficult to sort what guides the deeper movements of our lives. My anthropological mentor believes we rarely make decisions at all – not in the way we imagine. For me, this time in nature was a gift: space to listen, slow down, feel where the current pulls. I don’t know if I’m following reason or instinct. But I know this: by relocating what sauna wrote into my body long ago, I found my way home.