Here is the challenge before me: to explain death and dying and the past five years of my life in approximately 1,500 words. I opened my book Technologies of the Human Corpse (2020) with the following line: ‘I needed to finish this book before my entire family died.’ Now, in 2023, all of my family is, in fact, entirely dead.

My younger sister Julie Troyer died on 29 July 2018 from brain cancer. Age 43.

My mother Jean Troyer died on 28 May 2022 from colon cancer. Age 76.

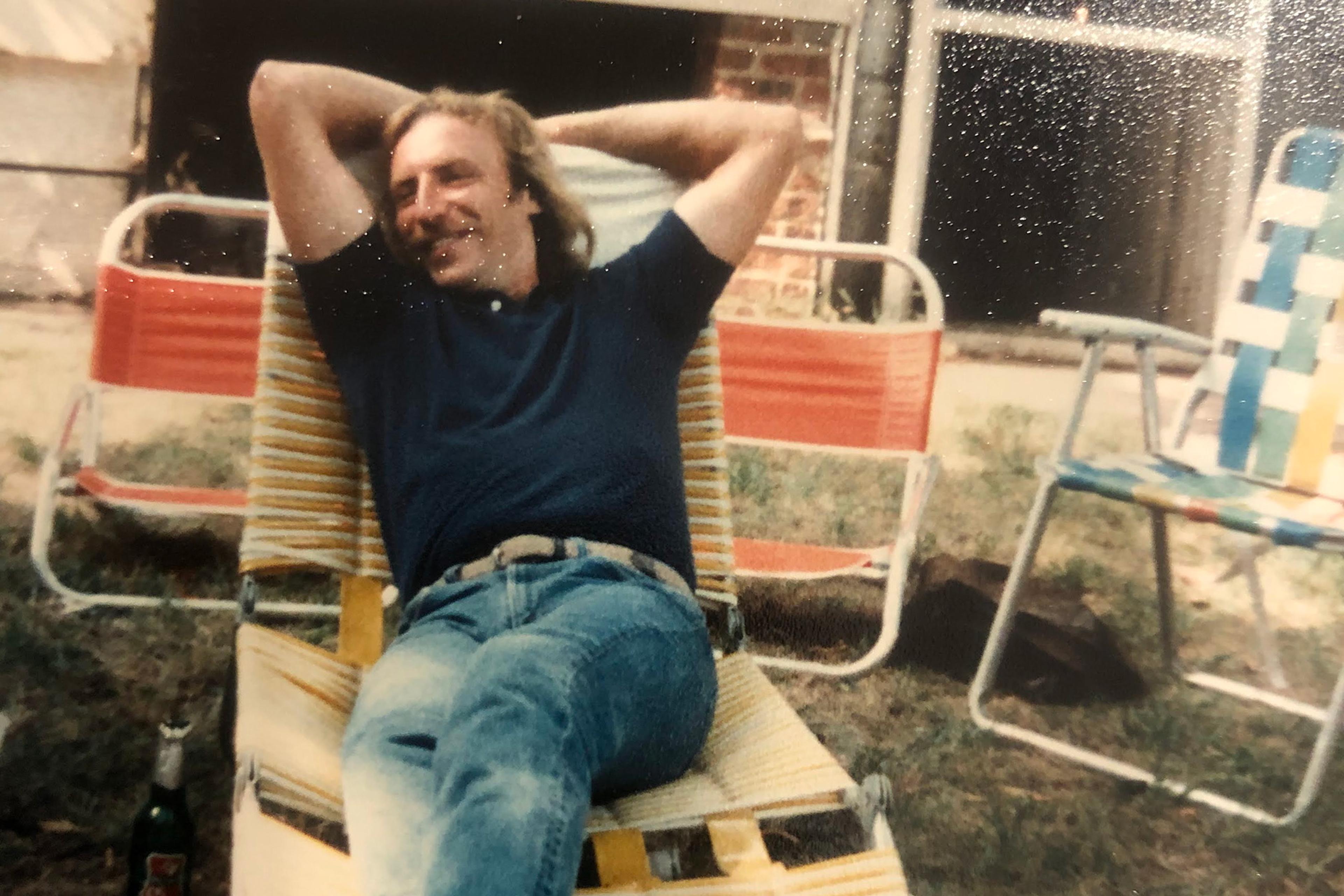

My father Ron Troyer died on 21 November 2022 from heart failure. Age 76.

And it has already taken more than 100 words to just explain all this and grab the reader’s attention.

Mom and Julie were already dead when Psyche approached me about writing this Idea exploring my work on the dead body and technology, but Dad was alive. My father would die two months later. I asked the editors at that time if writing about Mom’s death would be OK, and was assured it was fine since death remains a deeply personal experience alongside any postmortem technologies we might also encounter. Little did I know then that I would soon be contemplating how to also write about my father’s death, only six months and far too soon after Mom’s, and what being classified the sole surviving family member means. I always thought using expressions such as ‘sole surviving family member’ to be somewhat overly dramatic until I found myself writing it down on all the different forms I needed to complete after Dad died.

Being part of Death World (a term describing the wide spectrum of individuals and groups working on death, dying, and dead bodies) can give a person a certain kind of false assuredness verging on outright hubris that, when your entire family dies, you will know what is headed your direction in terms of grief and bereavement. You don’t know.

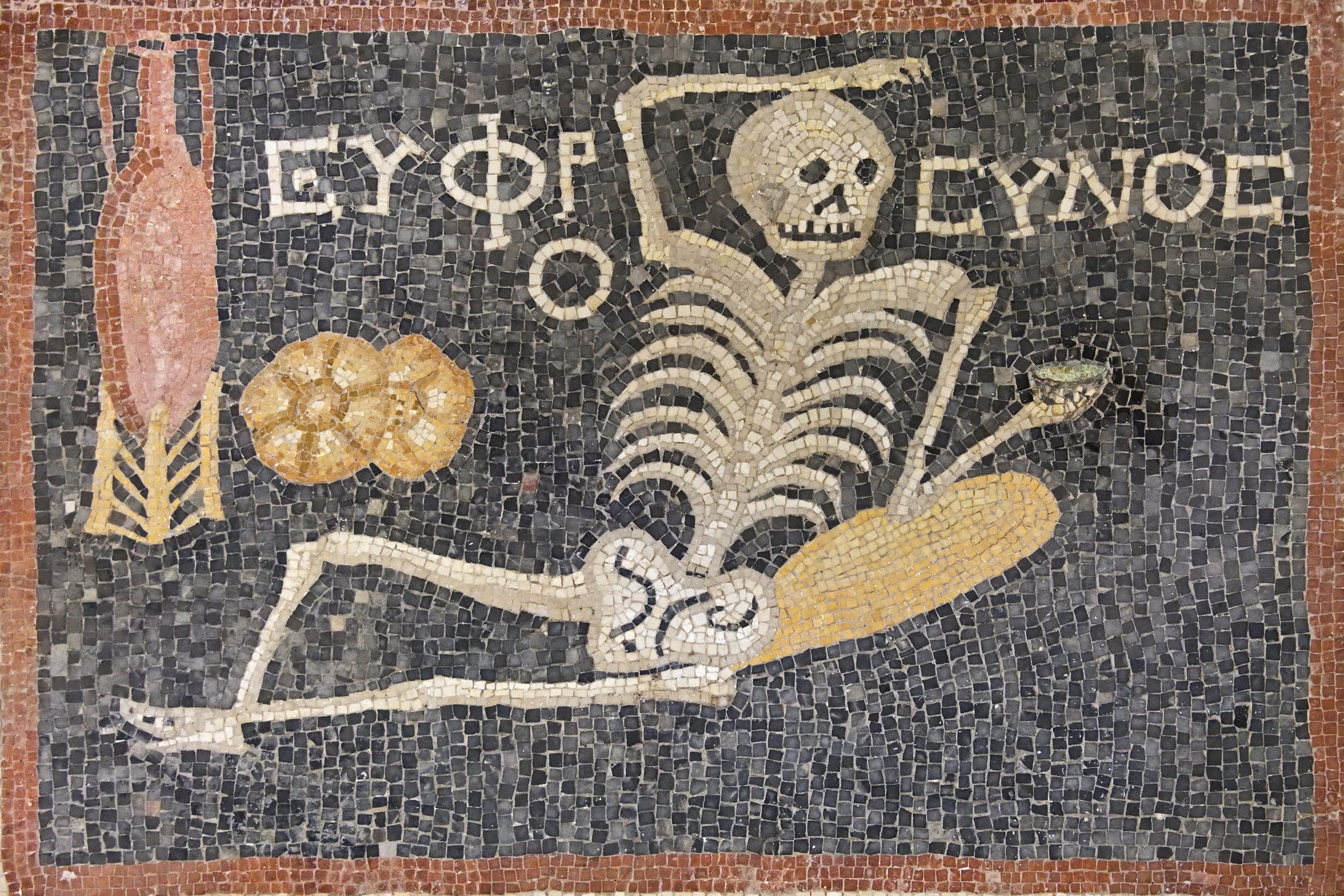

A good friend of mine, who is also a hospice nurse, fully captured my situation in an email after Dad died: ‘I am so sorry John – you have had a torrid time with successive bereavements of your family who are so dear to you. I always think the irony for those of us who study loss and death is that we still have to go through the process of grieving … it cannot be diverted by knowledge.’ When my book came out in 2020, I discussed my sister’s death in the preface and how I came to understand that death wins. Death always wins. I now more fully appreciate how this knowledge does not protect or shield those of us in Death World, nor should it, from acute loss. I am also, it turns out, not so different or special when it comes to every single grief and bereavement challenge I have confronted.

So, for example, trying to stay focused on finishing the task at hand is one of my biggest challenges, which I do know from the grief and bereavement literature is a key issue for many people. The home-based hospice group that took care of Mom assigned me an amazing grief counsellor who is now also talking with me about Dad’s death, a kind of double duty that I deeply appreciate. In one of our many conversations, I kept apologising for rambling and not getting to the point of anything I was trying to say since I just could not focus. Case in point, I’m now at approximately 600 words.

I should explain how I entered Death World in the first place. My father was a funeral director in the United States for more than 35 years so I grew up in the funeral business. We lived in a few states, but the bulk of this time was in Wisconsin. I would later pursue a PhD that enabled me to create a project that studied death and the dead body, which, for me, was a landscape I had known my entire life. I grew up around death – it is a physically tangible reality I have always known. After completing my doctorate at the University of Minnesota, I began a career as a Death Studies scholar working in Bioethics and Science and Technology Studies, eventually landing in the Centre for Death and Society (CDAS) at the University of Bath in the UK. CDAS was then and remains now one of the world’s only interdisciplinary research centres dedicated to studying death, dying, and the dead body. I built a home in Death World.

Only now, however, do I fully appreciate my hospice nurse friend’s wisdom per the non-protectiveness offered by the encyclopaedic knowledge we Death Studies scholars accrue and, for me at least, through the lived experiences of the same topics in my funeral-home youth. There are situations I am perhaps better at negotiating than some people, such as holding my sister’s, Mom’s and Dad’s dead hand after each of them died (which meant a lot to me) and then spending even more time with their dead bodies and talking with each of them before their respective cremations. I have always been comfortable around dead bodies, and thank my parents for normalising that experience before the time arrived for me to sit with their dead bodies. Still, other things caught me off guard, and that is how I want to finish this article.

And it took me only around 900 words to finally get to the point of it all.

Here are the things I knew to do before my parents died since I live in Death World. We spent time organising their financial affairs, funeral wishes, wills, advance directives for medical care (especially my Dad’s do-not-resuscitate order, which the hospital where he died followed 100 per cent, and, in my capacity as a bioethicist, I thanked the care team for doing), writing down all their logins and passwords, and generally making sure that (as the sole surviving family member) I knew where everything is/was located. Not everyone has the luxury of time or family support to make these things happen, but you should absolutely get these things done if you can. It can make the grieving a bit more manageable even if it is not any less numbing or painful. If you’re looking for a list of all the areas to cover, then the Coda to my book covers the key topics and gives you space to write things down.

Here is what I did not anticipate – the overall antsyness that made it impossible to sit still for any prolonged period, especially after Dad died. I already felt a compulsion to keep moving after Mom’s death, which meant I spent an inordinate amount of time at the gym and on the bicycle commuting to work. I am talking hours at a time for these activities. Then, when Dad died, I became really restless, which morphed into the need to always be moving and caused me to critically reflect on how and why Forrest Gump (of all film characters?!) felt the need to keep running. I also developed an out-of-character extreme lack of patience with legitimate questions that I deemed unimportant, all of which translated into a hyperactive malaise-based ability to achieve new levels of procrastination. Indeed – you need only ask the Psyche editors about said procrastination.

I had experienced elements of these personality traits in the past (I did complete a PhD after all) but never all at once and with such ferocity. I also knew from almost every single academic and popular press article and essay I read about grief and bereavement that this was normal. But even knowing it was normal felt a lot different when I was feeling all this happen – not just teaching these ideas to my students.

It was ultimately my students, I think, who helped me make it through everything that happened to me after both my parents died so close together. I teach a final-year undergraduate Sociology of Death course, and this year’s class coincided with Dad’s death. In fact, I was in the US when he died on Monday 21 November, and that Thursday 24 November I was on Zoom telling my students about my father’s death and how it was affecting me. I didn’t have to teach that class, and my head of department had already made it clear she thought I should not be teaching that day, but I wanted to do it. My family would want me to do it.

The students listened to me talk for 90 minutes straight, and I remain overwhelmed by the support they showed me and continue to offer me today. Oddly, I do not actually remember what I said during those 90 minutes. But I do know it saved my life. My students saved my life. Zoom saved my life, which, as a Science and Technology Studies scholar gives me some pause. Yet the one unexpected effect of me talking about what I was going through was that it also helped many of my students with their own death and dying concerns. One student explained it to me this way: ‘I know you are simply covering your work and passion; but I did want to say thank you. I have even had discussions with my parents about going into the industry. Anyway, what I’m trying to say is that I’m not as afraid of death any more.’

What that student said put me in tears, since I know that both my parents and my sister would absolutely want their deaths and how I discuss them to help other people. So, keep talking when someone dies. That is some of my key advice. Talk as much or as little as you want – but talk the way you want to talk. And keep talking.

More than anything, I am sad that my sister, Mom and Dad will never read this Idea even though I know each of them would fully approve of what I am saying here. They would also collectively point out that I have now written close to 1,700 words, which more or less says it all about the past five years of my life: grasping for all the words I can to describe the borrowed time I had with each of them, even though none of us knew it then.