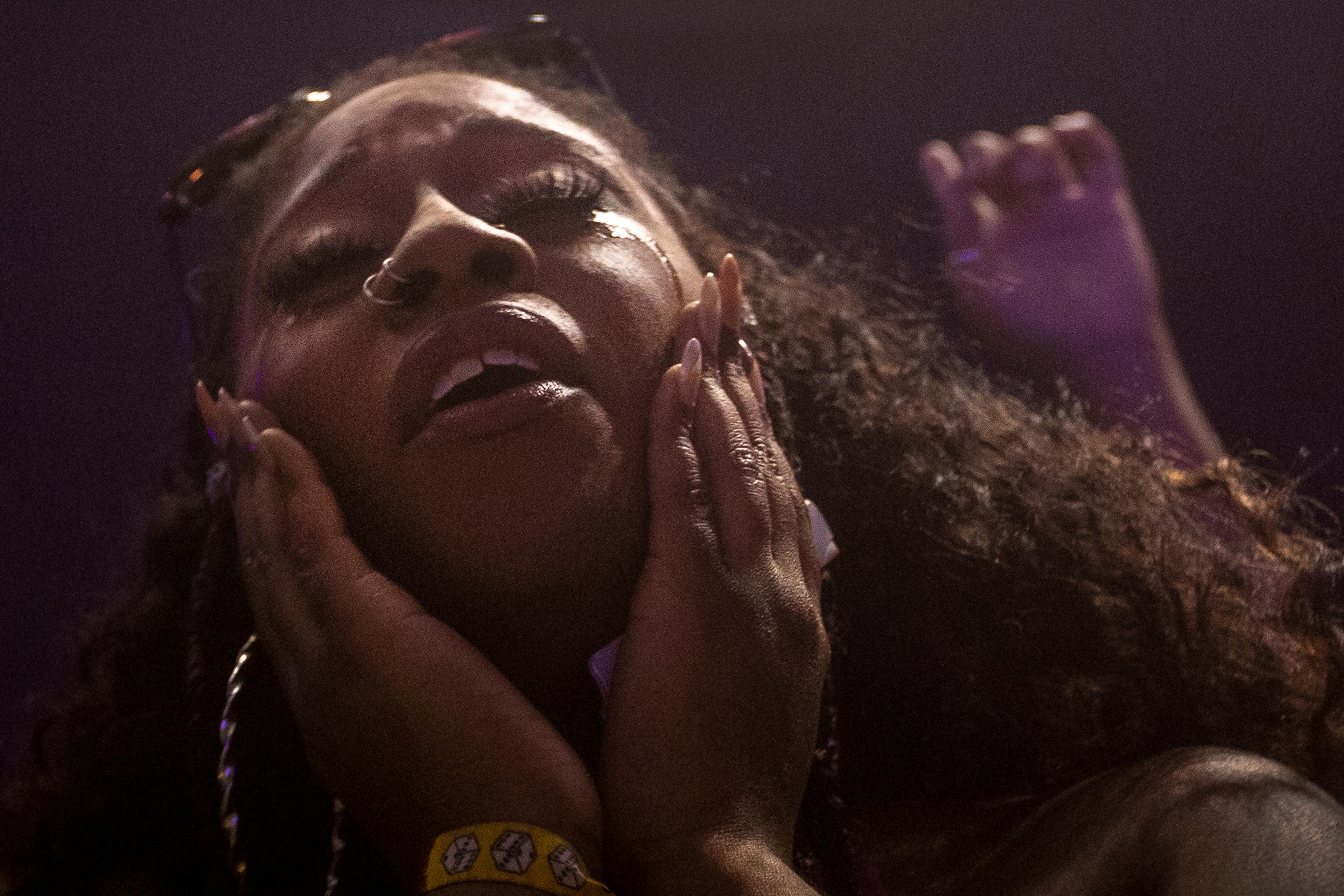

A baby sits quietly on his mother’s lap. Suddenly, their calm moment together is interrupted by a shrill and arresting sound – another baby is nearby, crying out in distress. The seated infant frowns and turns toward the crying, looking for its source. A moment later, his own face crumples, and he begins to cry too. His mother looks down at her previously comfy, recently fed infant, concerned and a little puzzled about why he’s started crying as well.

For adults, of course, hearing a baby’s cry is one of the most powerful social signals there is. It cuts through everything and is almost impossible to ignore. That’s no coincidence – rather, crying is the product of millions of years of evolution, adapted to signal need and elicit a caregiver’s response. Its acoustic properties activate the nervous system and compel us to take action. It also taps into one the most evolutionarily ancient forms of social connection: emotional contagion.

Emotional contagion is what happens when one individual’s emotions automatically trigger similar feelings in someone else. Think of contagious laughter: when you hear someone laugh, it can be hard to stop your own giggles bubbling up. Likewise, just hearing someone else sobbing might be enough to trigger a transfer of their emotions to you. This kind of emotional spreading helps humans and many other social animals respond effectively to their physical and social worlds.

Emotional contagion is thought to represent the foundation of human empathy. In his ‘Russian doll’ model, the primatologist Frans de Waal saw empathy as a richly layered process, a bit like a stacking doll or an onion. At the core of empathy sits emotional contagion – the automatic sharing of feelings – which combines with other cognitive and emotional skills to activate more complex, outer layers of empathy. With the combination of these abilities, rooted in an emotional core, a developing human can move from ‘feeling with’ the other toward ‘feeling for’ them, such as by comforting someone in distress or offering targeted help to someone in need. In other words, to show empathy for others’ experiences and feelings, we first need to be able to feel what they feel.

When and how does that begin? By studying infants like the one who was startled while sitting on his mother’s lap, scientists like us are finding out more about how complex abilities such as empathy emerge in early life, what they look like before they are fully formed, and what shapes their emergence.

The study of ‘contagious crying’ – where a baby cries after hearing another baby crying – goes back to at least the 1970s, when the psychologist Marvin Simner conducted a seminal experiment. Simner played different sounds to three-day-old newborns, including the cry of another newborn as well as artificial sounds. The sound most likely to cause a crying response was that of another baby in distress, which has been interpreted as evidence of early emotional contagion.

The contagious crying response has since been shown across multiple studies and infant ages. But researchers have questioned some of the methods used in this and similar studies, leading to renewed debate about what drives the phenomenon. Are infants reacting to the distress of another baby? Or do they just find the sound of another baby’s crying unpleasant?

Acoustically, crying is harsh, and other unpleasant sounds – like fingernails on a chalkboard or an alarm siren – can also trigger emotional reactions. It could be that crying simply has the same effect on babies. In a 2019 study comparing how toddlers reacted to real crying versus artificial crying (white noise that mimicked the rhythm and pitch of crying), toddlers responded negatively to both, frowning and showing signs of discomfort. While it’s possible that genuine crying causes stronger emotional responses than artificial crying sounds, we might not see that based on an infant’s behaviour alone.

Sudden emotional changes lead to changes in blood flow under the skin, which can be measured as temperature changes on the skin’s surface

The other big problem is that, as with much of psychology to date, most research on early childhood has been conducted in Western, high-resource settings, particularly in Europe and North America. Babies in these places represent only a fraction of the global population and are not representative of how most babies live in the world today, nor historically. Infants around the world grow up in vastly different cultures, each with their own social norms, including norms about expressing emotions. That might lead to differences in how emotional contagion manifests, even early in life. To understand how emotional skills develop and whether they are shaped by culture, scientists need to study babies from different backgrounds.

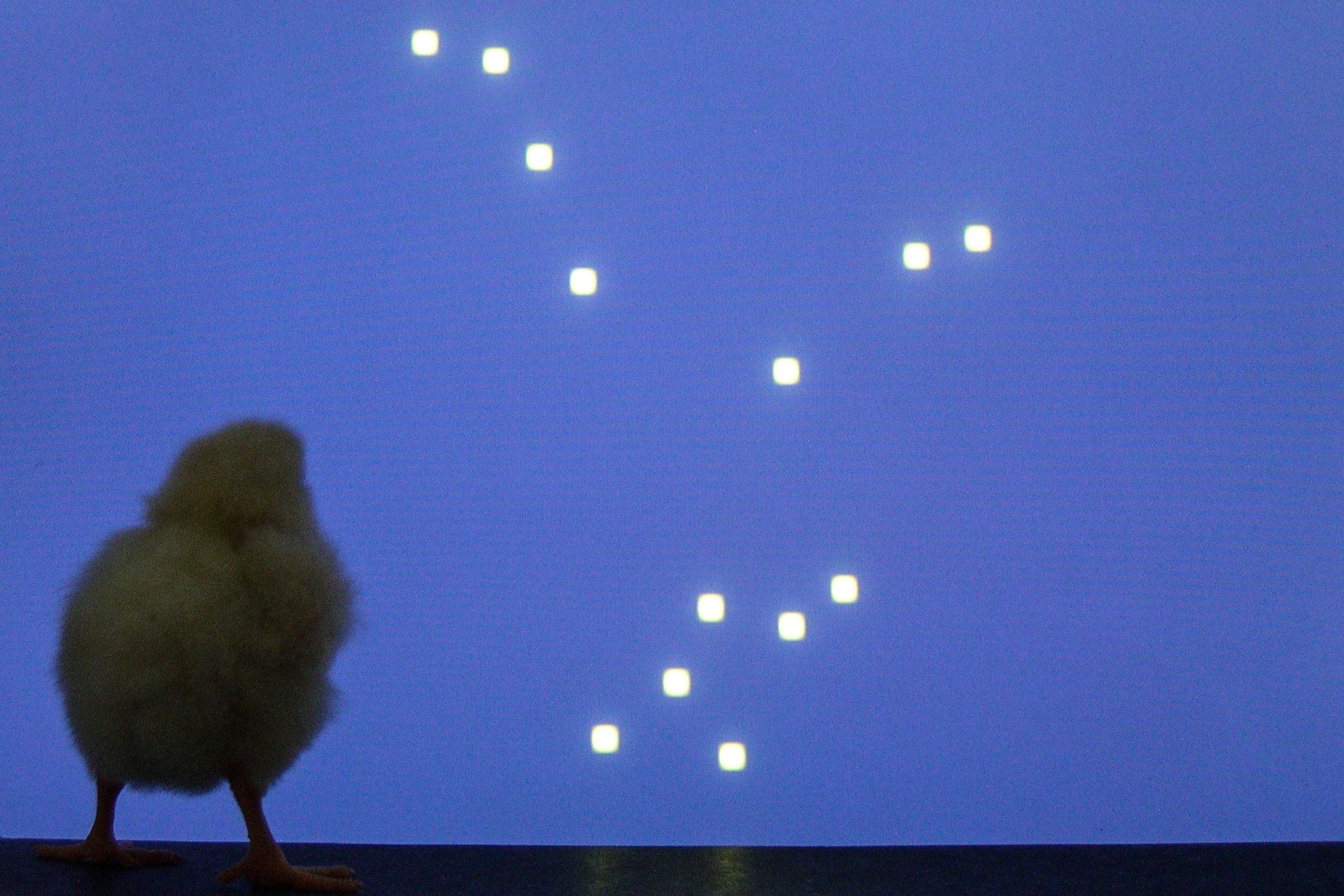

That’s what we did in a recent study, comparing how 10-month-old infants from three distinct cultural settings responded to hearing the emotional cries of their peers. These included infants in a rural region of Uganda (in a village near a rainforest reserve), an urban Ugandan region, and an urban part of the UK. In total, more than 300 babies sat on their mothers’ laps and listened to four different sounds from a hidden speaker: another baby’s crying, laughing or babbling, or an artificial sound that acoustically mimicked the features of crying.

Since a baby’s external behaviour gives only a partial picture of what their emotional experiences might be, we also brought in an important tool: infrared thermal imaging. Often used in airport health screenings or to detect dampness in buildings, infrared thermal imaging is now being harnessed by scientists to explore the inner workings of emotion, not only in humans but in other animals too. Sudden emotional changes – such as might happen when one hears a scream or a cry – lead to changes in blood flow under the skin, which can be measured as temperature changes on the skin’s surface. The tip of the nose is one of the best places on the body to reliably measure this.

So, we used a thermal imaging camera to measure changes in each baby’s nose temperature after they had heard another baby’s crying (or one of the other kinds of sounds). We also observed how the infants responded: did they frown or cry, smile or laugh?

Thermal imaging measures changes in facial skin temperature, which can tell scientists about underlying emotional states. (Image provided by authors)

We found that, across all three groups – rural Uganda, urban Uganda, and urban UK – babies showed the biggest changes in nose temperature and the strongest negative reactions to hearing another baby crying. They sometimes cried in response, though more muted responses like frowning were more common, suggesting that the infants coped better with our stimuli than those of some previous studies. As we expected, they reacted more strongly to real crying than to unpleasant artificial sounds. This suggests that infants in vastly different cultural settings are sensitive to the emotional nature of crying itself – a signal of distress that they can recognise and mirror in their own emotional state.

It seems that, from the first year of life, humans are tuning in to others’ emotions, even those of other infants. While this aligns with a general consensus that this component of empathy is likely innate and universal, there has been debate about the timing of its emergence in a person’s development, and there are unanswered questions about how and when it develops into more complex forms of empathy, and the role of cultural learning.

Our findings suggest that the building blocks of empathy are in place earlier than some may assume. In other research we are doing with these communities, we have found evidence that the same babies can also already perceive others’ needs and even try to comfort others in distress. For example, in a not-yet-published experiment using eye-tracking, we found that 10-month-old babies looked more at a character who needed help and were surprised when a different character (who didn’t need help) received it instead. In another study looking at the development of sympathetic concern, we found that, by nine months, some babies in Uganda and the UK tried to comfort their mothers following a (feigned) injury, such as by giving her a hug or a toy. Together, this suggests that long before they can walk or talk, infants possess a powerful capacity for empathy.

As babies grow and develop, this sensitivity can blossom into a deeper understanding of others’ emotions and motivation to care for them. And while sharing emotions is probably innate, research suggests there is still plenty of room for learning to foster the more cognitive components of empathy, including compassion.