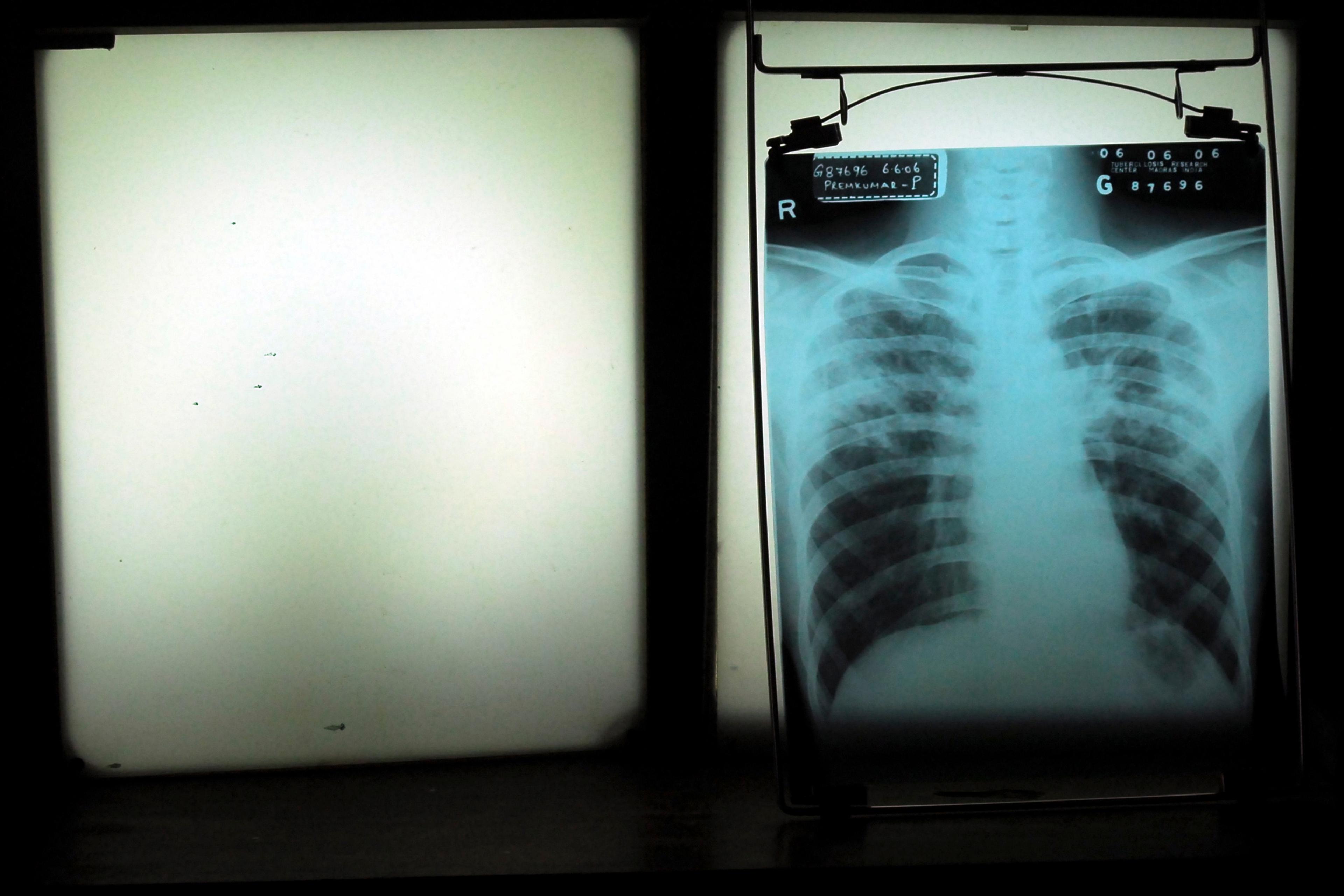

My mother was diagnosed with peritoneal cancer in May 2021. By all accounts, a terminal diagnosis. Lost and bewildered, with a deep ocean of questions, she searched for words of authority to cling on to. When she met with oncologists, she would ask how long she had. ‘How long do you have? Well, I can only tell you the average, but I’m not sure that is helpful. Everyone is different.’ Tell me when I might die, doctor, so that I might know how to live.

The words ‘three months’ were part of their reluctant speeches. They noted the difficulty with timelines, given that her cancer was rare. Still, simply presenting a possible timeline transforms an inchoate notion of death into a weed with roots, clawing deep into the subconscious. So the reality of death took root, and we housed it in our minds. It became a certainty, even as we remained uncertain about its timing – that is, how long my mother had left, and how much we could hope for.

‘Hope is the worst of evils,’ Friedrich Nietzsche wrote, ‘for it prolongs the torment of man.’ I have long viewed myself as a weathered realist educated in such schools of thought. Anything deviating from this perspective seemed like delusion or childish fantasy. But I now believe that this unrelenting view was not grounded in neutrality as much as I thought. I think it was embedded in fear – fear that separation from what was true would have devastating consequences. Eventually, I realised that this was not the separation that would devastate me.

After my mother was diagnosed, I felt conflicted. Should I encourage her to feel hopeful about her prognosis – help her believe that she would have enough time left to do all the things she wanted to? Or should I instead try to diffuse any clouds of hope that might appear, ensuring that none of us would fall prey to delusion?

As I began to grieve, I continued to think that allowing myself to feel hopeful would serve only to loosen my grip on the reality of the situation. I felt I had to take on the role of rational medical professional to balance out the spirituality that came with our cultural heritage. It seemed as though I had only two options: hope or truth. I tried to pre-emptively deny any denial, tried so hard to look my mother’s death in the face. But it ran against my instinct to comfort her.

This internal tension felt most urgent when I witnessed the difference in bedside manner between UK and Egyptian medics. My mother, a Coptic Egyptian woman, sought to arrange her affairs in Egypt and, while doing so, she became unwell. I sat at her side as the medical men cited God in their discussions: Inshallah, all will be well. Until, one day, I heard them dispose of these faithful words after we stepped away from her bedside. My father and I asked for a hushed, out-of-sight clarification of something they had said to her that suggested there was more that could be done to improve her condition. ‘Could we really do something?’ we asked. ‘No, of course not,’ they answered. It felt as if their words of comfort were untruths, and sometimes I came away from those ‘hopeful’ conversations with a feeling that I had let her be lied to, that I’d let her down. I saw their attempt to imbue hope as a façade, somehow cowardly. It evoked a sense of injustice in me.

The certainty of denial can make one incapable of finding middle ground

And yet: what harm did she suffer? I saw the joy on my mother’s face when a doctor was willing to give her another round of chemotherapy. It meant that she was no longer a thing to be given up on (Well, Mrs Boules, we had a good run…) Hope returned her sense of agency. She was worthy of fighting for, so it made her fight. A lot of people don’t like analogising having cancer to being in a fight, but what I witnessed my mother do could really only be characterised as fighting – and ‘winning’ such a fight need not be defined in terms of additional years of life.

What I realised, in time, is that there is an important distinction to be made between hope and denial. The psyche doesn’t always have space for reality’s sharp edges, but denial as a general approach is not helpful, especially if it interferes with someone’s ability to make decisions about medical treatment or sorting their affairs. To me, denial involves a misplaced certainty: ‘I’m sure it’s nothing.’ ‘No, of course you’re not going to die.’ It is a rebound from one assaultive thing to its opposite.

In some cases, what sounds like hope might actually be better described as denial – as when someone who has received a serious diagnosis confidently ignores medical advice under the guise of ‘hoping’ that it will all go away, or feels sure that it’s something a natural home remedy will fix. If there’s a tone of certainty, then it might be denial. Whereas, if someone thinks that an alternative treatment might work, they probably won’t put all their eggs in that one basket. They won’t allow denial to obscure their chances of survival with other approaches. The certainty of denial can make one incapable of finding middle ground, reducing things to deceptive binaries.

Hope is more ambiguous than that. Hope is a thing uncertain, and I think this uncertainty is what makes it the perfect antidote to the certainty of death. Melanie Klein, a key figure in psychoanalysis, observed that infants find it hard to integrate two opposing values into one object: my mother is good when she provides milk, or she is bad when I want milk and I do not get it immediately. It is hard to imagine that she is not an either/or entity because if she were both, it would make for a very uncomfortable psychic space. With maturity, we learn to integrate opposites into one thing. This is a lifelong process, and this integration is known as the ‘depressive position’: it is the realisation that a thing can be both bad and good, so it can be hard to know how to feel about it.

Ironically, we can repurpose the ‘depressive’ challenge of uncertainty into something hopeful. It is hard to be certain about the nature of a thing – or, in my mother’s case, the timing of a thing. We can fixate on the certainty of death, or we can learn to sit in the discomfort that we do not and will not know when this inconsiderate dinner guest will show up, so we might as well just get on and eat.

When hope is present, it encourages health-promoting behaviours such as eating well and exercising

As long as hope is not being used as a façade for denial, one can see how it could be safely introduced at the start of a person’s cancer journey. It might sound something like: ‘Based on the literature, average life expectancy is short. But if you look after your diet and mental health, then you’ll be more likely to tolerate the treatment and maintain a healthy lifestyle. Then you might have a better chance, and I encourage you to aim for that.’ Of course, it takes more than one conversation to communicate this kind of nuanced message; in our initial discussion with my mother’s doctor, all we could take away was that there was an attack on her life.

Hope protects us from an all-or-nothing mentality. In the absence of hope, one might think it pointless to nurture a life that seems to be approaching its end. But there is evidence that when hope is present, it encourages health-promoting behaviours such as eating well and exercising, which themselves might improve outcomes. A nutritious diet promotes immunity and helps recovery between treatments; cardiovascular fitness and muscle mass improve treatment tolerability; hope can modify pain perception, and might make a person more likely to want to adhere to treatment; and so on. Granted, the evidence for better survival rates among people with greater hope is not particularly compelling. However, a single statistical value cannot encompass the complex journeys of each patient and the ways in which their post-diagnosis experience might be lightened by hope.

We should encourage hope in those with other forms of serious illness, too, though it should not be done in a rigid way. As a psychiatrist, I’m conscious that, for people with mental health conditions, simply applying the word ‘hope’ could come across as banal and condescending. In depression, for example, hope is fundamentally missing; it might be nice to hear that ‘things can get better, even if you don’t see it,’ or it might be highly irritating and isolating, making you feel that the person saying it has no idea about the depths of despair someone can fall into. Explicit discussions of the concept of hope might not always be appropriate while a person is at the heights of a psychiatric episode. But I and other clinicians would not engage in our work at all if we didn’t believe there is hope for our patients. If someone can provide hope when others can’t, it can keep the wheels turning until they begin to move on their own again.

When my mother passed away, it was nearly three years after her diagnosis. Was it her hope that gave her more time than expected? Maybe. Regardless, I don’t want to sell hope as a means to a longer life. I want to promote it, instead, as a foundational aspect of humanity, as a necessity for living, whatever the length of one’s life might be. There is nothing untruthful, I have learned, about embracing hope. The only irrefutable fact is that nobody knows what will happen with complete certainty.