You may have found yourself tearing up at the movies or after hearing certain news. And you may have also found yourself discreetly wiping those tears away, lest you seem overly emotional. Cry me a river, as the jazz standard goes. But are emotional tears really a sign of being irrational?

Modern evolutionary biology suggests a new take on this question: emotional tears – similar to reasoning and other mental traits – have been relentlessly optimised by natural selection for survival and reproduction. Your tears are, in a sense, rational. As adaptations that confer advantages in certain contexts, they are ecologically rational and shot through with strategic calculation.

Working out how tears provide these benefits requires what evolutionary scientists refer to as an adaptationist analysis – a kind of cost-benefit calculation (along with Asmir Gračanin, we recently published a formal version of this analysis in the journal Evolution and Human Behavior). Evolution, like a business, operates on the basis of a strict bottom line. Developing, maintaining and running adaptations involves material and metabolic costs. If these biological machines generate benefits that exceed their costs, they persist as part of the species’ makeup. If not, selection eliminates them – just as cavefish evolved eye loss in their dark habitats.

Amphibians evolved tears about 360 million years ago to prevent eye desiccation when on land. Keeping eyes in working ophthalmic order (lubricating them and nourishing them via basal and reflex tears) seems beneficial enough. But what benefits might emotional tears produce that offset their costs?

Emotional tears seem to repurpose the ancient tears for valuable new signalling functions. They have several properties that make them good signals: they are produced non-permanently; they have a rapid onset and offset, thereby demarcating transient states or events; and they draw attention, because people tend to focus on others’ faces, particularly their eyes. As indicators of physical distress, tears may have been easier to detect than other internal or external cues. These background conditions may have led the human brain to evolve adaptations for individuals to produce tears to signal their distress, and for observers to infer others’ physical or emotional distress from their production of tears.

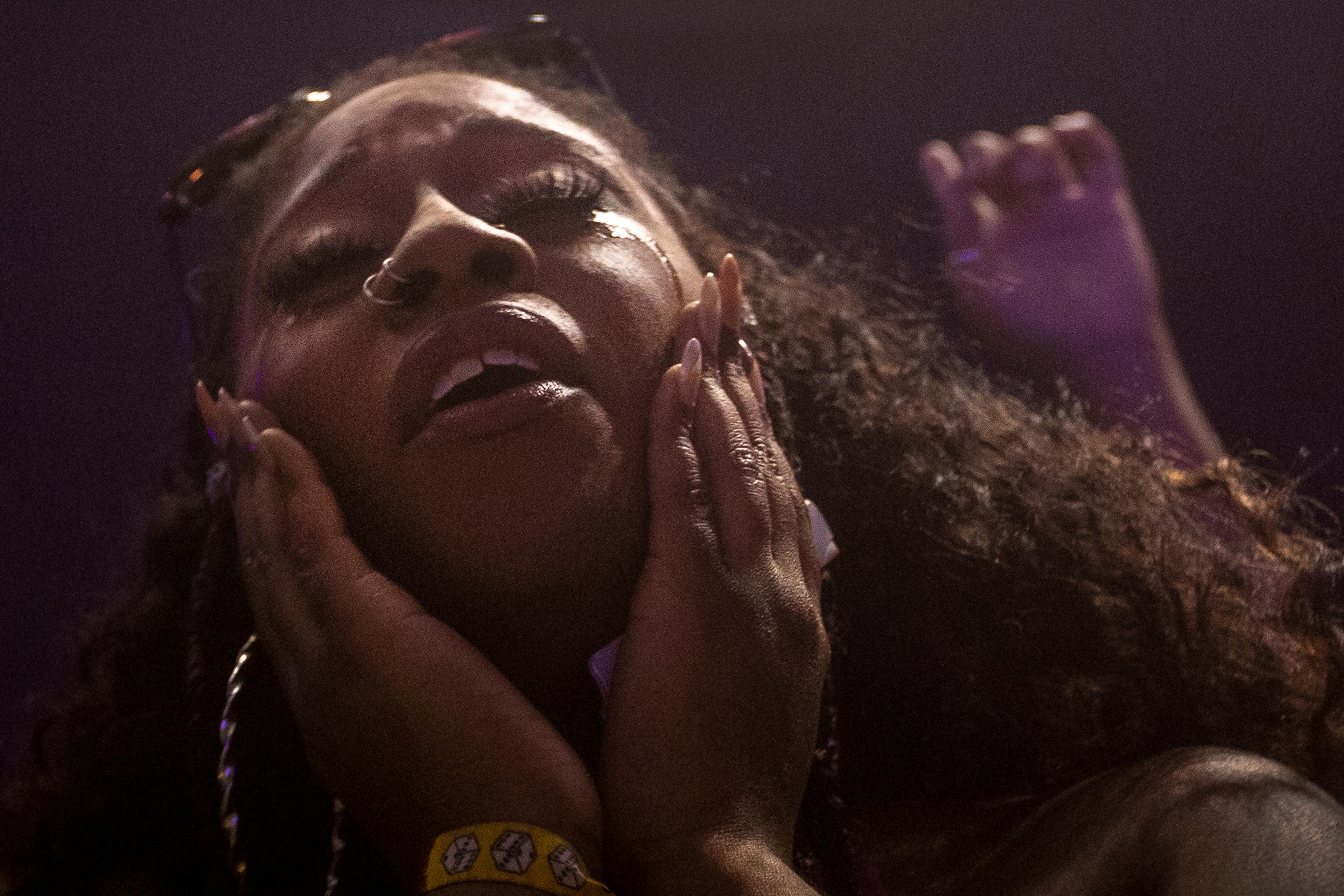

That emotional tears serve as non-verbal signals of distress is suggested by what elicits them: current, anticipated, recalled or imagined negative events – death, separation, rejection, injury and hunger. (Of course, tearing can also occur in response to positive events such as weddings, childbirth, celebrations, acts of kindness, achievements and artistic performances – we’ll return to this phenomenon shortly.)

Another indication that emotional tears serve communicative functions is that they occur more often in the presence of others. For instance, as parents know, people often delay crying until a supportive person is nearby. Additionally, those with romantic partners cry more than singles. Lonely individuals – despite reporting lower wellbeing – cry less than those who feel socially connected. These facts suggest that emotional tears are non-verbal requests for help rather than mere reflections of distress. Causing others to stop mistreating you, or to give you food, assistance or support in a conflict with third parties may be some of the ways in which emotional tears pay for themselves.

Droplets running down your child’s cheeks are meaningful but droplets running down your car’s windshield are a non-event

To persist across generations, signals must also pass muster with their recipients. If receivers hadn’t come to see emotional tears as credible indicators of what the signaller was trying to communicate (eg, suffering), tears would have failed to generate net benefits and would have likely been selected out. Emotional tears may have remained mostly credible because faking them is difficult (though well-trained actors and people with manipulative tendencies can do it). Moreover, while crying may get you help, chronic crying makes others see you as weak and ineffectual – a less desirable social partner, especially in adulthood. English speakers aren’t kind to cry-babies, drama queens, wimps, snowflakes, waterworks, softies, wets and namby-pambies. So there’s an in-built incentive not to overdo it. Also, tears blur vision, making it harder to fight or flee during conflict – this may act as a built-in cost, or ‘handicap’ in biological terms. All these factors would have helped to keep emotional tears credible.

The messages that tears communicate are fundamentally about value – more specifically, the tearer’s evaluations of internal or external events affecting them. Consider again what people tear up about. You might cry if your spouse abandons you (but not if they leave home to run an errand), or if a blackout ruins $800 worth of frozen food (but not $2 worth), or if you fracture your femur (but not if you scratch your thigh). The negative evaluations that trigger crying surpass a certain threshold. The same goes for positive evaluations. You might cry if your child reaches a culturally meaningful developmental milestone (but not for a minor one like learning a new word).

Much of this might seem obvious, but only because humans have complex evaluative and communicative machinery – and because we assume that this is true about humans in general. Because of this, you view droplets running down your child’s cheeks as meaningful but droplets running down your car’s windshield as a non-event.

Tears convey the tearer’s internal evaluations not for their own sake, but as means to an end – to tweak the mental states and behaviour of others in ways that favour the tearer. For example, tearing up may cause your boyfriend to stop doing something that bothers you. And when and to whom we cry involves its own set of delicate calculations.

Many conditions must be in place for the tearer to actually receive help

To be clear, these calculations are not carried out consciously or deliberately, like solving a calculus problem. But the brain performs them automatically all the same – much like how the visual system uses binocular disparity to compute the depth of objects from two-dimensional retinal projections, without any effort or volition on the part of the observer.

One especially interesting case is when the intended target of the tear signal is also the source of the tearer’s suffering. The sufferer may not be able to compel the target to stop if they are weaker or less capable. But all is not lost for a sufferer with lower leverage because they can coax the target with a tearful, indirect threat that tacitly communicates: ‘Impose fewer costs on me (or provide more benefits) or, because your fate is tied to mine, you’ll suffer indirectly through my continued suffering.’

This is a peculiar bid, and many conditions must be in place for the tearer to actually receive help. The target of one’s tears must interpret the tears as sincere, see the tearer as truly lacking the means to solve their problem, be capable of helping and, most importantly, value the tearer’s welfare. In addition, the target of one’s tears must think that helping will somehow benefit them more than not helping.

There is now a substantial research literature on tearing and crying, and the findings show that people cry precisely in these situations. For example, research shows that people are more likely to tear up when they feel they’re bearing heavier costs. Among nurses in Thailand, for instance, crying occurs more often when they are feeling overwhelmed by their caring responsibilities. Correspondingly, observers infer greater suffering from the presence of tears. In courtroom settings, for example, people are more likely to believe that tearful children – compared with non-tearful children – were sexually assaulted. Other research demonstrates the effect of interpersonal value. For instance, people tend to offer more support to tearful friends than to tearful strangers. Tearful individuals implicitly recognise this and tend not to cry as much in front of unresponsive audiences. For example, children are more likely to express sadness, including through tears, when they are near their parents than when they are with peers, regardless of how much time they spend with each group.

And what about tears of joy? These make up a nontrivial minority of tear episodes. These tears may function less to prompt immediate action and more to prompt observers to register what the tearer positively values. Thus, tears can express not only distress but also gratitude, pride and emotional connection. Tears of joy may also serve as signals that yield benefits for the tearer himself. By marking an experience as deeply meaningful, such tears can guide observers toward a more accurate understanding of the tearer’s values and priorities. In turn, this can elicit responsive behaviours – such as personalised gifts, increased support or affirmations of closeness – that benefit the tearer and strengthen social bonds.

Perceivers can often distinguish between positive and negative tears based on the context. For example, if you see a friend tearing up during an artistic performance or while gazing at the Grand Canyon, chances are those tears reflect positive evaluations.

We can use an adaptationist approach to answer further questions about tears. For example, why do some people cry more readily than others? Adaptationist thinking suggests that those with relatively lower aggressive formidability and wherewithal will tend to cry more. Indeed, women across cultures are much more likely to cry than men, and children cry more than adults.

It could be that suppressed tears paradoxically elicit more support than unbidden crying

What about the vocalisations people make when tearing up? Upon observing tears, observers seem to probe the situation to assess how much cost the tearer is bearing, how much cost it would take them to help, etc. But tearers conduct their own audits as well. For example, the tearer wants to know whether the intended target detected their tears and recognised them as signals of suffering. If not, the appeal for help may need to be adjusted or intensified. Sobs, whimpers, sniffles and other vocalisations may function to intensify the signalling.

If tearing and crying have the social functions that we’re proposing, you might be wondering why people sometimes cry when alone? In fact, many adaptations that are believed to serve social functions, such as language, and emotions like anger and shame, can likewise be activated when the individual is alone. Simulation, planning and recalibration are possible reasons why these adaptations, including emotional tears, sometimes activate in solo mode. For example, a vivid simulation of a catastrophic event may elicit sadness and tears.

The social function of crying also raises the question of why we sometimes try to suppress our tears. Our answer to this is that humans are complex, and while tears can elicit help, they can also lead others to view the tearer as weak and ineffectual. Also, tearing can elicit help from observers, but those observers may try to rule out exploitative appeals before helping. And as our colleague David Pinsof noted, suppressing tears may help the tearer conceal any intentions he may have to exploit the goodwill of others. While we are not aware of data on this point, it could be that suppressed tears paradoxically elicit more support than unbidden crying.

So, next time you tear up at a movie or see someone crying over bad news, take a moment to appreciate the cognitive complexity behind those tears. They reflect the outcome of evolutionarily ancient evaluative and emotional systems that guide our behaviour adaptively. On a purely physical level, they are water-based mixtures containing electrolytes, mucins, oils and enzymes. But, at the same time, they are so much more – part of a sophisticated signalling process that is vital to the success of our social relationships.