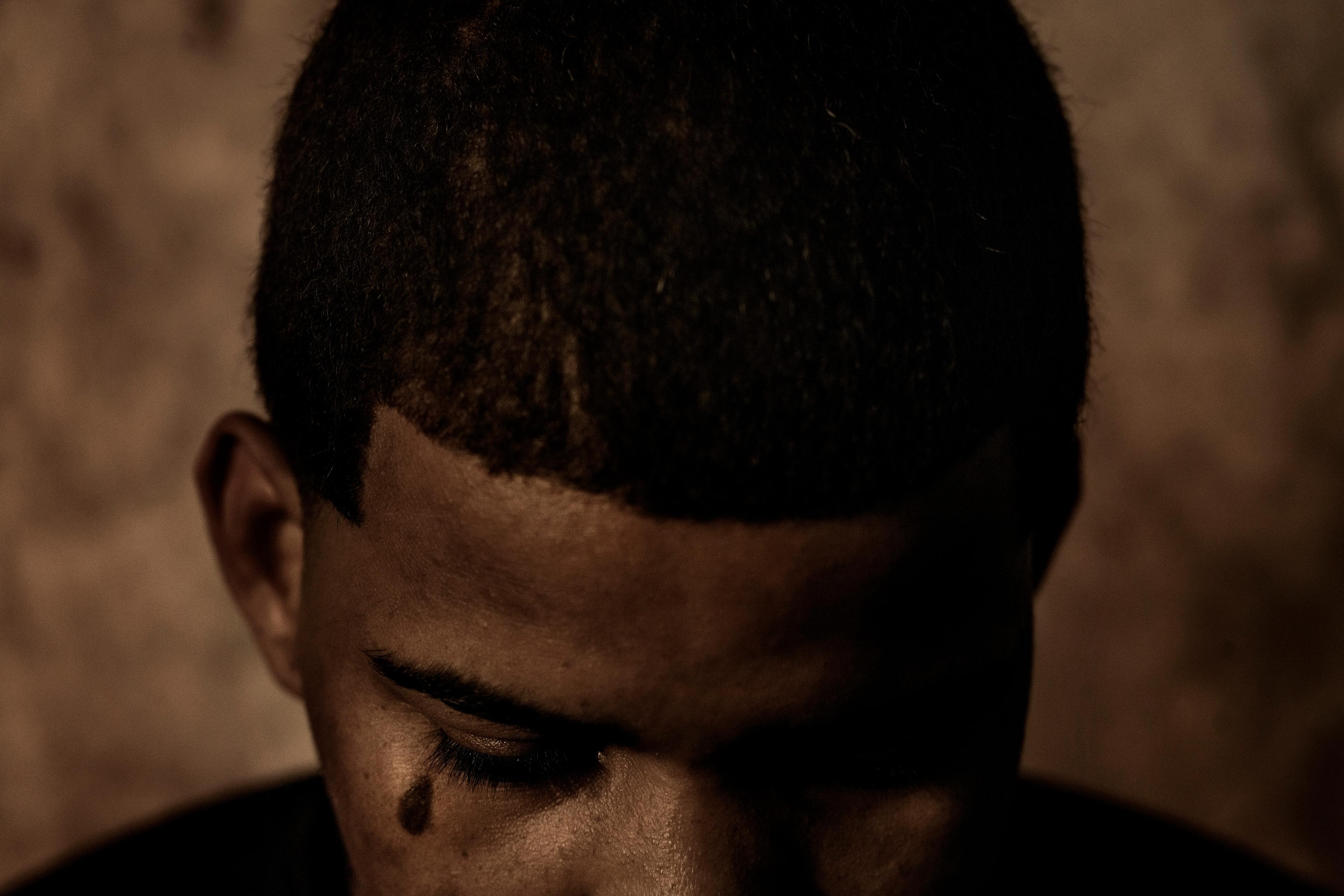

Elias can’t sleep. He lies awake at night in the small apartment he shares with his son and daughter in Australia, his thoughts racing. Images of his past experiences in Syria run through his head. His thoughts return to the night he awoke to the sound of gunfire and the smell of burning. His son and daughter were sleeping in the same room; he took hold of them and fled to the nearby forest. On the way, he saw a fleeing neighbour shot in the back by a militant. Elias’s wife and baby daughter had been staying with a relative nearby but, amid the fighting, he was not able to locate them, nor could he find them in the weeks that followed. After two months of searching, Elias and his children had the opportunity to escape the country. He was devastated to leave behind his wife and daughter, but felt he had no choice if he wanted to keep his older children safe.

In Australia, Elias finds it hard to adjust. He feels like he doesn’t deserve to start a life in a new country when he doesn’t know what happened to his wife and baby daughter. He avoids talking about them with others, fearing that he will be judged for leaving. At the same time, he is overwhelmed by the injustice of what he has seen. The image of his neighbour haunts him. He has fantasies about finding the men who did this to his family. He feels like he has lost his faith in humanity and is now cautious around strangers. He wants to create the best life he can for his children, but he’s not sure he can move on.

There are currently more than 100 million people worldwide who have been forced to flee their homes due to war or persecution. More than 32 million of these people now reside outside their country of origin and are known as refugees. Research suggests that refugees experience elevated rates of psychological disorders such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression as a result of being exposed to traumatic events like those in Elias’s story. These conditions can have profound and long-standing effects on someone’s ability to live a fulfilling life. PTSD has been traditionally conceptualised as a fear-based disorder, resulting in symptoms such as intrusive and distressing memories, recurring nightmares, and hypervigilance. Depression is characterised by pervasive feelings of hopelessness and a loss of enjoyment.

But these are not necessarily the only traumatic reactions a refugee experiences. Elias – a fictional person whose story is based on real cases – is plagued by anger (towards the people who harmed his family and friends), guilt (for believing he abandoned his family) and shame (for believing he has failed as a father and husband). These ‘moral emotions’ are common among people with refugee backgrounds and can undermine a person’s sense of worth, hope for the future, and ability to connect with others. While a number of psychological treatments for PTSD are effective in reducing fear-based symptoms, it is unclear how effective they are in redressing reactions such as anger, guilt and shame. There is some evidence to suggest that these feelings may be less responsive to, or even interfere with, the effectiveness of traditional PTSD treatments.

One framework that can help with understanding these responses – and with developing ways to alleviate them – is moral injury. Moral injury has been defined as the psychological impact of witnessing, enacting or failing to prevent acts that transgress moral values. It was initially conceptualised as a way to understand the psychological impact of ethical dilemmas in warfare. Clinicians and religious providers observed that active-duty military personnel and veterans struggled with the consequences of killing others in battle, as well as with instances of perceived institutional betrayal – for example, being ordered by a commanding officer to do something they felt was wrong, such as killing a civilian.

Moral injury has thus been described as arising from two types of experiences. The first involves others acting in ways that transgress one’s morals. For Elias, this includes witnessing the attack on his village. The second type involves oneself acting in ways that transgress one’s own morals. Elias experiences this, too: even though he thought he had no choice, leaving part of his family behind felt like a moral transgression. Both of these types of experiences are associated with a constellation of psychological changes, including increases in negative emotions and decreased trust in others. Typically, this phenomenon is understood as ‘moral injury’ when the changes are pervasive, uncontrollable and incapacitating.

Many refugees have been exposed to moral transgressions carried out by others, such as the murder of loved ones or being the target of persecution, imprisonment or violence. Many too have faced ethical dilemmas such as being forced to separate from family or friends. And psychological reactions such as those described above have been repeatedly documented in refugees and conflict-affected populations. Therefore, the concept of moral injury may offer some important insights into the psychological consequences of the refugee experience.

To understand how moral injury manifests in refugees, our research team has conducted a series of studies investigating whether the strength of ‘moral injury appraisals’ – that is, the extent to which someone is troubled by past behaviours that they consider morally wrong – underlies some of the adverse mental health outcomes that refugees experience.

We have found substantial evidence among refugee communities from Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq and Sri Lanka that stronger moral injury appraisals are associated with greater PTSD and depression symptoms – even when we control for the effects of each individual’s amount of trauma exposure. This suggests that the morally transgressive nature of certain events experienced by refugees causes an added degree of distress. We have also found unique associations with mental health depending on the type of moral transgression. Specifically, people who are haunted by the moral transgressions of others tend to report elevated PTSD symptoms, depression, anger and suicidal ideation, while people who are consumed by their own perceived moral violations report elevated depression and anger. In research yet to be published, we found that being troubled by one’s own and/or others’ moral transgressions was associated with increased negative beliefs about the self, difficulty with managing strong negative emotions, and difficulties with trusting, and connecting with, others.

Importantly, moral injury may not just be linked to traumatic events that occurred in one’s home country, but also trauma and stressors encountered while residing in transit and resettlement countries. For instance, we found that individuals encountering more daily stressors in their resettlement country, such as financial hardship, discrimination, visa uncertainty and lack of work rights, also had stronger moral injury appraisals. Significant hardships in the resettlement country may be perceived as moral transgressions enacted by others (eg, via government policies) or by the self (eg, ‘failing’ to deliver their family to the safe haven they had promised).

The identification of moral injury as a potential factor in the emergence of psychiatric symptoms after trauma represents an important step in developing interventions that can help reduce the burden that many refugees feel. A number of promising interventions have been created to target moral injury, including a form of psychotherapy called ‘adaptive disclosure’ and another approach called the ‘impact of killing’. However, most existing treatments for moral injury have been designed for military or veteran populations. They may be less directly applicable to many refugees due to their focus on moral transgressions in warfare and military institutions. There are some interventions, including cognitive processing therapy and cognitive therapy for PTSD, that have been investigated with a handful of refugee and conflict-affected groups, but there is a need for more rigorous evaluation of their effectiveness in reducing moral injury-related responses in refugees.

It may be beneficial to develop a comprehensive intervention that targets the specific types of moral injury experiences reported by refugees, connecting these to past events and focusing on their social as well as their emotional impact. For example, a mental health professional may help an individual who has difficulty trusting others to first understand how their belief about people’s trustworthiness has been shaped by a traumatic event they experienced, before considering how applicable this belief is now that they no longer live in a warzone. The individual may also be supported in initiating, and restoring, friendships and other social connections in their new country.

There are millions of people around the world who have had experiences similar to those of Elias. These experiences are multi-layered and complex, and often involve multiple types of violations and losses. Refugees may not be able to reclaim all that has been lost as a result of persecution, war and displacement. But new insights on moral injury could open viable avenues for supporting their psychological recovery, with the hope of helping refugees move forward with their lives.