In our tumultuous present, mindfulness and meditation can seem like attractive ways to process difficult feelings and emotions. Meditative practices have long been a support strategy for traditional cultures facing collective trauma, and a method for bringing individuals and communities into mutual solidarity. Tibetan refugees, who have lived through cultural genocide, use meditation and ritual to join with their spiritual ancestors. In this way, they experience their own suffering as a doorway into compassion for others.

Tibetan culture, through its resilience, kindness, intelligence and joy, has inspired millions of people in the West to take up meditation. But are the practices that many of us turn to the same in substance as the rituals that other communities have relied upon for centuries? In most cases, the answer is no: they have a profoundly different orientation and, significantly, they lack the crucial communal features that make traditional meditation so vital and nurturing for the brain and body. In fact, modern meditation can often work against us – reinforcing our separation from others, rather than strengthening the social bonds that are needed to overcome adversity and barriers to compassion.

The traditional and modern approaches to meditation are shaped by two distinct visions of the person. Those in traditional contemplative cultures typically understand persons to be constituted by their relationship to others, as the historian David McMahan notes in The Making of Buddhist Modernism (2008). As a consequence, practitioners first learn to experience themselves in meditation as empowered and supported by the care, compassion and wisdom of their spiritual ancestors and community. By contrast, citizens of the modern West often see persons as individual selves that exist prior to the community – atomistic individuals who choose whether or not to enter into relationships.

These different conceptions of the person have important consequences for meditation. In the modern view, practitioners tend to think of meditation as an autonomous project of self-help: through their own efforts, they try to foster beneficial states of mind. Socially conditioned in this way, Westerners enter into ‘lovingkindness meditation’ (metta) as a way of summoning up a sense of love for themselves and those they feel close to; then, for those they’re neutral towards; and, finally, for people they dislike.

For traditional Buddhist communities, any such meditation wouldn’t begin with an atomistic self who is trying to generate a positive mindset from scratch. In such cultures, practitioners begin meditation with rituals and prayers that remind them that they are part of a connected community, blessed and supported by a lineage of spiritual ancestors that spans many generations. This starting point is shared by contemplative and ritual forms of Buddhism, Christianity, Confucianism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism and many indigenous religions. In Tibetan Buddhism, for example, meditators envision a field of refuge that includes buddhas, bodhisattvas, spiritual teachers and other inspiring figures, who bless and sustain them and their world within qualities of unconditional love, compassion and wisdom. Practitioners’ efforts to cultivate those same qualities begin not with self-help, but with the support and empowerment of their teachers and communities. In this way, the person meditating learns to become an extension of that field of love and compassion in which they are held, by progressively extending love and compassion to others.

This kind of deeply supportive framework, found in all contemplative traditions, is mostly absent from modern meditation programmes. Because these communal dimensions of blessing and empowerment are embedded in premodern, ritualised cosmologies, they are often deemed an unneeded byproduct of ‘primitive cultures’, which can be jettisoned in order to ‘modernise’ the practice. However, these cosmologies serve a valuable function that maps directly onto attachment theory, one of the most influential approaches to developmental and social psychology.

Attachment theory is based on the idea that the care that children receive in infancy stays with them through their lifespan – for better or worse. Infants who receive sensitive and responsive care go on to develop a self that they feel is worthy of love. In turn, this supports their curiosity and courage to explore the world, because they trust that a source of security and support is available when needed. Sporadic or unreliable care, on the other hand, fosters insecurity and a distrust in support from others in times of need.

But the experience of security and insecurity is not locked in at infancy. Feelings of security and insecurity accrue throughout one’s life from relationships with peers, mentors, romantic partners and so on. This means that we all have traces of security and insecurity in different relational contexts. Through the lens of attachment theory, the ritual and devotional practices of traditional contemplative cultures, which are repeated many thousands of times throughout a person’s life, offer a powerful field of care in which practitioners experience themselves as recipients of love, compassion and wisdom. From this secure base, they are empowered to extend sustainable, inclusive and unconditional care to others.

From an evolutionary perspective, humans come prepared with capacities for care and compassion. But without the experience of actually receiving care, people can develop inner psychological blocks to compassion – including a lack of inner security, courage and confidence. Lack of security can foster aversion to others’ suffering, a sense of isolation and biases against others. These psychological barriers interact with and are reinforced by systemic inequities such as racism, classism, sexism and homophobia.

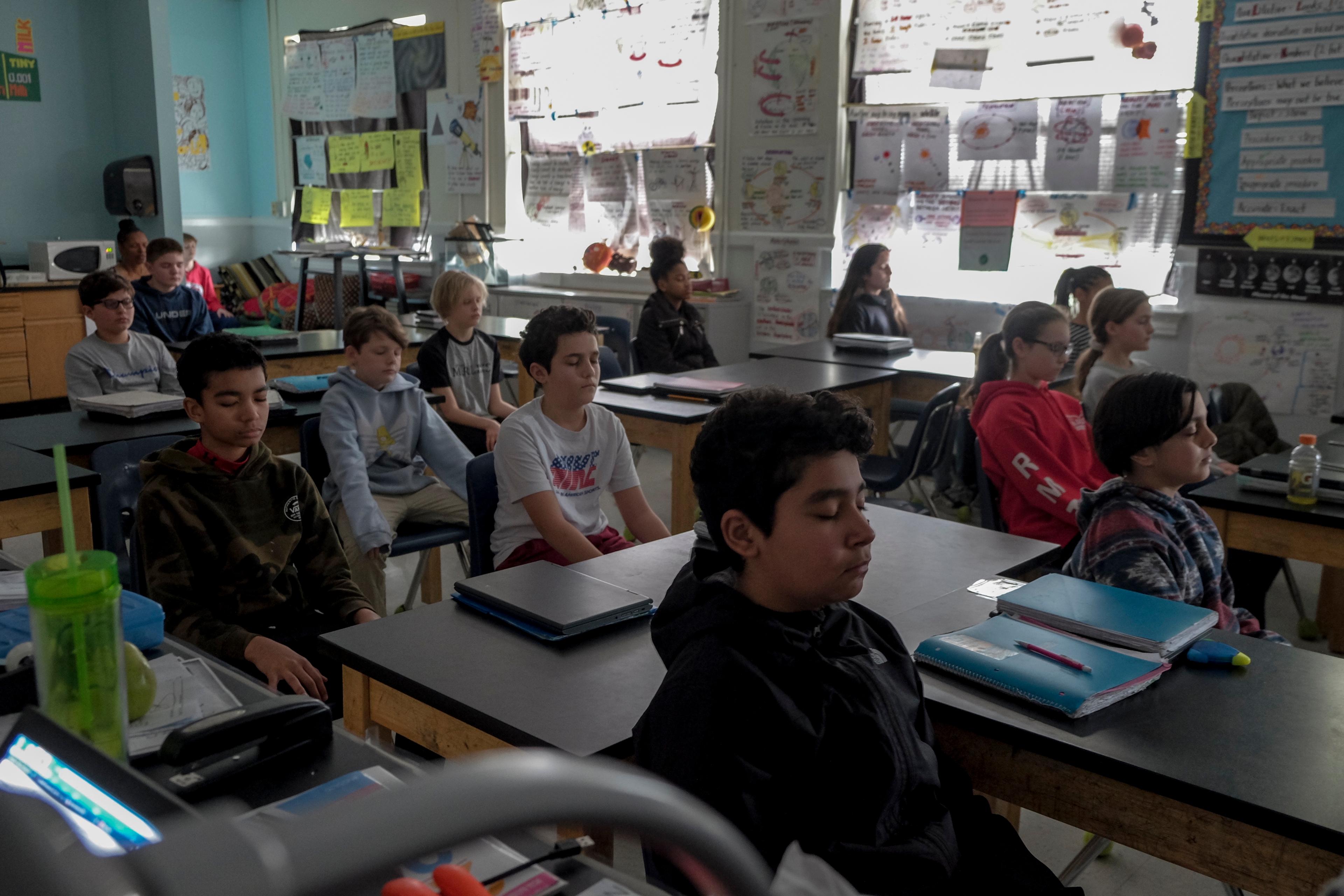

Modern meditation and mindfulness, by beginning with an atomistic sense of self, can increase an individual’s sense of disconnection. They can present meditation as a passive source of comfort for the self, instead of a practice that uses discomfort to create solidarity with other sufferers. In her book American Dharma (2019), the Buddhist scholar Ann Gleig documents how communally oriented meditation can help people to become conscious of socially conditioned traumas, to heal internalised racism, and to tolerate the discomfort that conversations about race and privilege can generate.

Traditional cultures of compassion training strive to dismantle barriers to compassion by bringing to mind a field of care in which practitioners are held and supported, and from which they can learn to hold and support others. This relational starting point promotes resilience and connectivity, and bolsters the psychological and social resources we need today to confront systemic injustice. But how might secular people in modern individualistic cultures gain access to such communal benefits?

Research findings in psychology show that feelings of security can be temporarily increased, including among people who have predominantly insecure attachment histories. Social psychologists developed a method called attachment security priming, in which participants are asked to visualise a moment of receiving care from a loving figure, a trusted friend, or simply by thinking of words such as ‘love’, ‘safety’ or ‘care’ for a moment. These simple priming exercises temporarily increase feelings of security, safety and courage. In turn, participants are more likely to offer help to others, have more patience listening to others’ difficult emotions, and possess less bias against other groups. This research suggests that attachment security priming could be integrated into meditation to recover the relational basis of the practice.

In an article forthcoming in the journal Perspectives on Psychological Science, we introduce a relational starting point of support for meditation, derived from traditional Tibetan practice, and informed by research on attachment security priming. There are various ways to engage a relational starting point for meditation, depending on one’s own life experience, background and worldview:

- You can recall a simple moment of supportive caring connection with another person, from any time in your life, and re-inhabit that caring moment as if it’s happening now – evoking a rich experience of loving qualities and energies in mind and body. For example, Paul can call to mind playing cards with his loving grandmother at her kitchen counter, and John can recall a moment visiting a joyfully welcoming aunt as a young child.

- A second option is to bring to mind someone to whom you feel grateful for their impact on your life, and experience the uplifting quality of imagining that person as present with you now.

- A third option, if you practise in any spiritual tradition, is to bring to mind a saint, divine figure or field of spiritual ancestors, with whom you feel a deep connection.

- If none of those options resonate, you might recall a time you spent somewhere special to you in the natural world – a place that felt deeply welcoming or peaceful. Or recall a loving moment with a pet. Or bring vividly to mind a moment when you were a loving presence to another person.

According to theories of embodied cognition, when we recall any such caring moment, it is simulated and re-enacted in multiple systems of the brain and body, including perceptual, motor, visual and affective systems. During the caring moment practice, we can visualise and simulate a felt sense of security, by experiencing that moment as if it were happening now, along with its attendant qualities of care, love, warmth, acceptance, peace and wellbeing.

The ability to simulate experiences in our minds is a remarkable feature of the human brain. Mental simulation has helped athletes establish the skills necessary to perform at their peak under the most challenging circumstances. Similarly, by repeatedly simulating and re-inhabiting moments of supportive caring connection, we can establish a core of inner safety and compassion that can be returned to again and again. This inner core can serve as a secure base to process our painful feelings in a healing way, and to generate a more sustaining power of care and compassion for others. It can also provide the emotional resources needed to courageously challenge painful and oppressive social systems.

The social distancing required by the pandemic has made us newly conscious of many simple caring moments in our pre-pandemic lives – greetings from co-workers, visiting a friend, pushing a child’s swing, or joining friends on a beautiful day. The relational starting point of meditation shows us that we can continue to recall and reinhabit those moments. That helps us to build and access an inner font of security and compassion that we then draw upon to become a more stable, caring presence to ourselves and others. This core of security can assist us to notice the ways that we have been conditioned by systems of oppression and individualism – and, hopefully, to rise above them.