Time magazine named ‘The Protester’ its 2011 Person of the Year amid Occupy Wall Street, the Arab Spring, and anti-austerity protests in Europe. This was before the Gezi Park demonstrations in Turkey, Hong Kong’s Umbrella movement, the Women’s March in Washington, DC, the Yellow Vests movement in France, Indian farmers’ protests, and Black Lives Matter, to name just a few historic uprisings since then. Globally, protests more than tripled between 2006 and 2020. Gauging by current turmoil surrounding the war in Gaza, our ‘age of mass protests’, as it’s been called, is not about to end any time soon.

But to truly change history, it is not enough for the masses to rise up; they must subsequently win concessions such as ceasefires, fair elections, environmental protections, or new policies that promote racial justice. While protests continue erupting with remarkable frequency, they are also failing, at historic rates, to achieve protesters’ stated goals. As Time hailed the power of the protester, the rate at which mass protests succeeded in meeting their objectives was plummeting, from two in three during the early 2000s to just one in six by the early 2020s.

Activists are now reaping less fruit from their labour, while many would-be activists never take the plunge in the first place because they reasonably doubt that their participation will make any difference. Why aren’t protesters winning like they once did, and what would make protests more effective?

Some scholars pin declining protest success rates on social media, which allows huge crowds to assemble without building the organisational structures and strong networks necessary to effect meaningful change. Others blame dictators’ use of ‘smart repression’ techniques, including censorship, propaganda and misinformation. As the political scientist Kurt Weyland points out, counterrevolutionaries have historically held an advantage over revolutionaries because they are willing to bide their time, heed advisors, and do their research on which repressive methods have worked in the past. Revolutionaries, in contrast, tend to leap into action, sometimes miscalculating their odds of success and choosing misguided strategies.

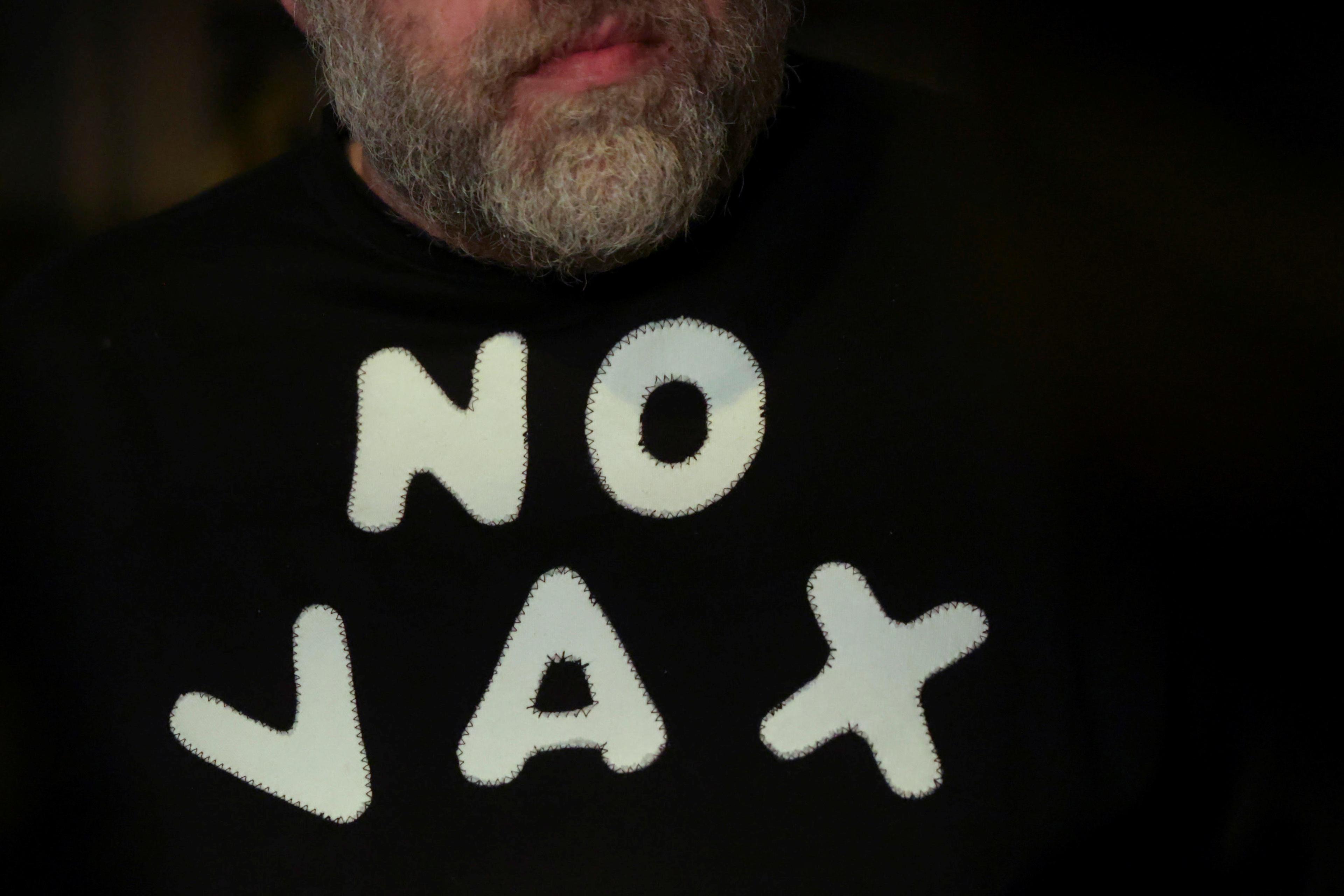

By following their instincts, protesters risk adopting tactics, such as shouting the most incendiary slogans that come to mind or throwing rocks at police officers, that not only fail to help them meet their goals, but even backfire. For example, there is evidence that, in contrast to nonviolent civil rights protests of the same era, violent protests in 1968 fuelled voter support for law-and-order Republicans – tipping the US presidential election toward Richard Nixon and away from the Democrat Hubert Humphrey, the lead sponsor of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Protesters today have an opportunity. They can claim more victories if they take better advantage of what I call, in my recent book, ‘the new science of social change’ – the latest scientific evidence on what protest tactics tend to produce the best results. In terms of positive outcomes such as building public support for a cause, pressuring officeholders to implement favourable policies, or spurring desired institutional reforms, some approaches have been shown to work better than others.

The evidence that scientists have uncovered might confirm the prior intuitions of some seasoned activists and challenge the assumptions of others. Among the key insights into what tends to be (in)effective, researchers have found that:

- Violence seldom pays. From 1900 to 2006, nonviolent resistance campaigns were more than twice as effective as violent ones (though even nonviolent campaigns have struggled to achieve their goals in more recent years). One reason why violence backfires is that it discourages new activists from joining or otherwise supporting a movement. I ran an experiment in which I randomised whether social movements were described as violent or nonviolent, and asked people how willing they were to join and donate. Subjects were significantly less eager to participate in violent movements than peaceful ones, and donated between $15 and $20 less to violent movements on average. One survey respondent stressed: ‘I WOULD NOT WANT TO BE A PART OF ANY MOVEMENT THAT SANCTIONS VIOLENCE.’ Nonviolent protest can still be misrepresented, of course. Some experiments suggest that nonviolent protesters from racial minority groups are viewed as more violent and more deserving of repression than protesters from racial majority groups.

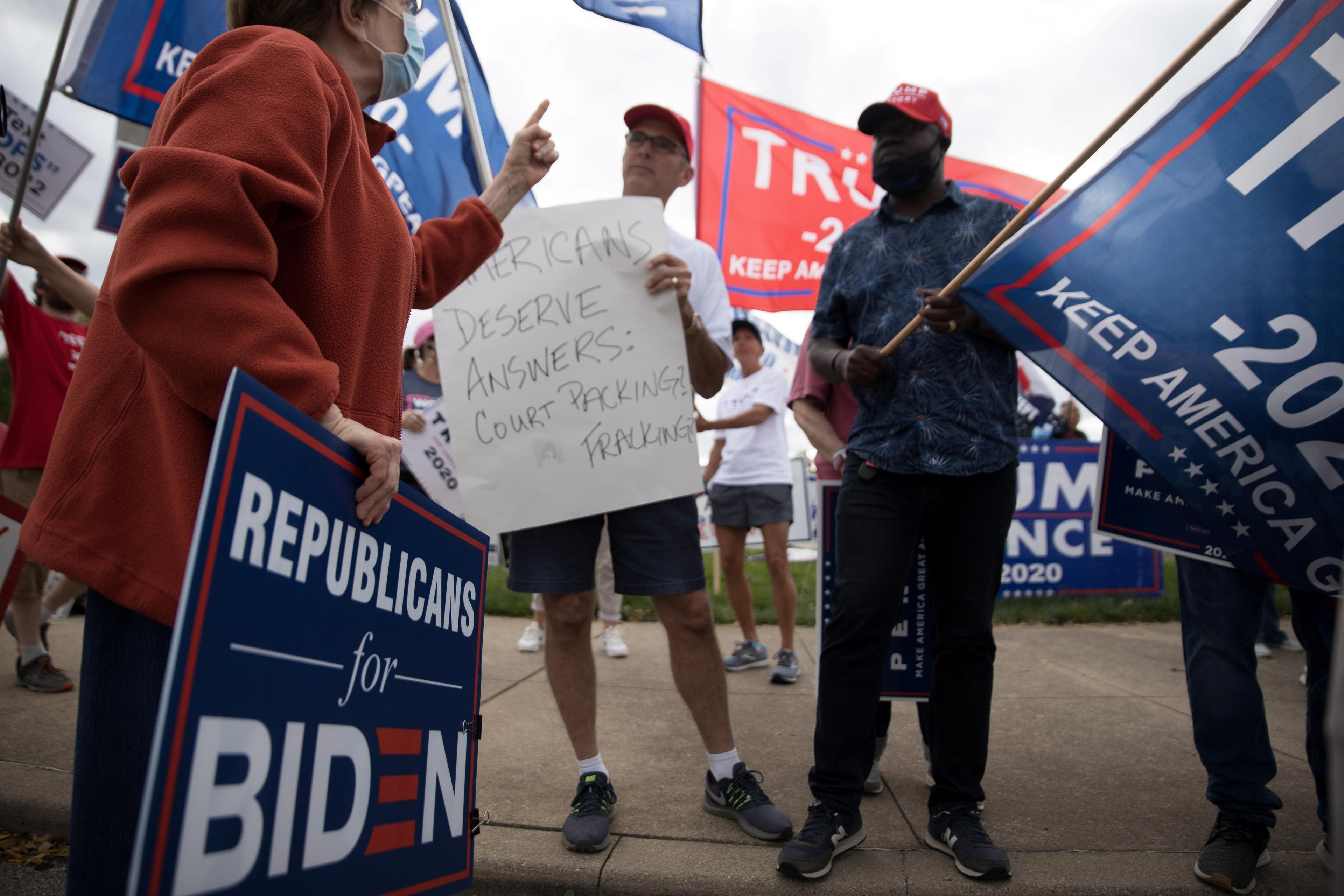

- Cohesive demands are more persuasive than mixed demands. This may be one reason why the 2017 Women’s March in the United States, which featured a hodgepodge of progressive demands – from reproductive rights and social welfare to environmental safeguards and racial justice – won few concrete policy concessions, whereas the March for Life, with a singular message about banning abortion, contributed to the historic reversal of Roe v Wade in 2022.

- Diverse coalitions signal that a movement is more than a radical fringe. When students at universities protest the war in Gaza, it is easy for some observers to write them off as the ‘usual suspects’; students have staged anti-war demonstrations for generations. But when their professors or other allies join them, people take notice – and might also take the protests more seriously.

- Marginalised protesters influence lawmakers more than privileged protesters. Low-income and BIPOC protesters pay higher costs – in terms of repression, foregone income and psychological distress – than more privileged protesters. Knowing this, lawmakers may be more responsive to marginalised protesters, who must mean business if they are willing to incur such costs to voice their grievances. For more privileged protesters, talk is cheap.

- Visible repression boosts sympathy for demonstrators. For example, when police in the US used violence against peaceful civil rights demonstrators in the 1960s, the media were more likely to frame protests in terms of ‘rights’ rather than ‘riots’. While repression is not desirable, if it does happen, activists can bounce back by calling it out and cultivating public sympathy.

There are plenty of scientific studies revealing other noteworthy aspects of how people respond to protests. For instance, the public tolerates protests by some women more than others: ‘patriarchy-defiant’ feminists are judged more harshly than ‘patriarchy-compliant’ women protesters who accentuate their roles as mothers and wives. Larger crowds are not necessarily better than smaller crowds if they provide no new information to powerholders about people’s concerns. And ‘slacktivism’, a low-cost, online form of activism, can actually boost overall participation in a campaign, providing a gateway to deeper activism and making once-fringe ideas (such as universal healthcare or gay marriage, in the US) seem more mainstream.

We live in a golden age for rigorous research on effective activism, thanks to improved data availability, statistical innovations and the increased use of randomised experiments in the social sciences. Meanwhile, the ‘evidence revolution’ has transformed decision-making in areas ranging from medicine to sports. When navigating high-stakes situations, many people increasingly rely on empirical evidence rather than gut instinct: patients expect clinical trials proving the safety and efficacy of vaccines; political candidates hire armies of pollsters to guide their campaigns; athletic managers pore over data to draft the most promising rookies. The evidence revolution is based on the principle that real impact matters as much as, and perhaps more than, good intentions.

But the evidence revolution has not yet taken root in actual revolutions. Protesting remains a largely emotional experience rather than a calculated one. While there is nothing wrong with protesting to express emotions, protests have the potential to accomplish much more than catharsis. The philosopher William MacAskill emphasises that legalised slavery probably would not have fizzled out on its own; abolition was contingent on ‘moral weirdos’ launching an international movement and ultimately triumphing. Protests shape the lives and livelihoods of millions, provided that they can effectively tackle weighty issues such as slavery, poverty, tyranny or the climate crisis. So why haven’t activists widely embraced scientific evidence that could give their movements a boost and tilt the odds back in their favour?

Some colleges and universities are revising their tenure and promotion standards to recognise socially engaged scholarship

The answer lies in the growing rift between activists and scientists. Academia in the 21st century rewards hours in the lab or office, not hours marching in the streets. This incentive system alienates protest scholars from protesters and can make academic prescriptions sound arcane, condescending or inauthentic. A common protest chant goes: ‘People power, not ivory tower!’

Fortunately, there are ways to bridge the divide between activists and scientists. One way is for universities to hire professors with backgrounds in social movements, which was more common in the 1960s and ’70s, but might be politically delicate today. Another is for academic and philanthropic organisations to encourage scholars to partner with community changemakers. Some colleges and universities, including mine, have recently revised or are considering revising their tenure and promotion standards to recognise socially engaged scholarship.

Social scientists can listen to protesters’ concerns and tailor their work accordingly without compromising rigour. And activists could consider outside experts as potential allies in their struggles for a better world. Here’s a recent, personal example: my students were planning a walkout to protest the war in Gaza, and they sought some feedback. As part of their planning, the student protesters had asked faculty to cancel classes during the walkout so that they would not miss any coursework. When some of the students asked what I thought about their plans, I referred them to the research showing that costlier protest sends stronger signals than lower-cost protest. That suggests that organisers of walkouts might want to consider staging them without asking for class cancellations – or even walking out in the middle of an exam to show how serious they are by risking their grades for a cause.

While much of the latest research on effective activism remains quite technical, other social scientists and I are doing what we can to translate our findings for activists to use on the ground. If the trend of sagging protest success rates is ever going to be reversed, it will require innovation and open-mindedness from scholars and activists alike.