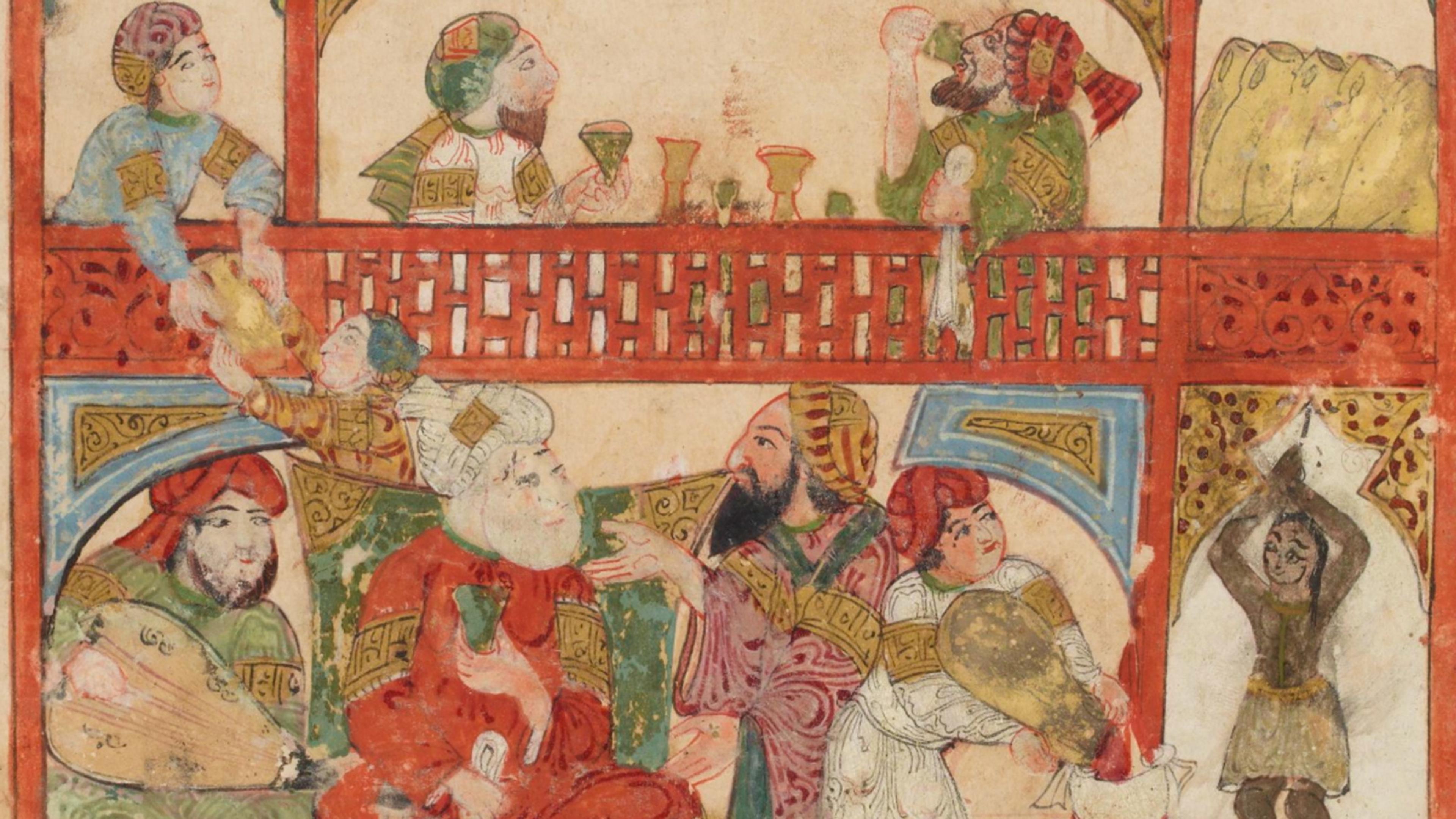

Al-Jahdami, a scholar in 9th-century Iraq, always got invited to the best parties. His neighbour knew this, and would throw on his best robes and follow close on his heels – close enough that the host would assume they were together, and the doorman would let them both in. And thus would al-Jahdami’s neighbour crash the most luxurious gatherings of the mighty Abbasid Empire, which, given the cultural and material wealth of the region, were probably some of the best parties on Earth.

One day, when al-Jahdami got invited to the prince of Basra’s feast, he decided to put an end to his neighbour’s opportunism and, in the middle of the banquet, in front of all of the other guests, implied that the prophet Muhammad looked askance at party-crashing. Uncowed, his neighbour responded at once with another quote from the prophet – a quote with a more reliable provenance than that cited by al-Jahdami: ‘Food for one is enough for two, and food for two is enough for four, and food for four is enough for eight.’ This reminder of the importance of hospitality struck al-Jahdami dumb with shame. The party-crasher triumphed.

Stories of party-crashing (tatfil) were a popular theme of medieval Arabic literature, and this particular story inspired al-Khatib al-Baghdadi, a historian in 11th-century Baghdad, to compile a collection of such tales. These stories were more than just light-hearted forms of entertainment. As is clear from the anecdote above, with its reference to the prophet and the value of hospitality, the medieval Arabic party-crasher had layers. I will uncover these layers for you here, one by one.

The first layer is the person you already know: as in movies such as Wedding Crashers (2005), this person goes to the party uninvited, usually in search of love or food, and hijinks ensue. He has tricks up his sleeve – he might pretend to be a caterer or blend in with a group of invited guests. This happened mostly in medieval Baghdad, and the carefully referenced stories of his antics are presented as true. We might learn something from these stories about, for example, how to behave at a party, but we are, above all, entertained. This is the layer that first drew me in. I was a student, looking for laughs, and al-Khatib al-Baghdadi’s Kitab al-Tatfil (‘Book of Party-Crashing’) did not disappoint. Jokes and witty poems appear side by side with advice on how to make the most of a good party. (Here’s a hot tip: ‘If your place at the table is too small, say to whoever’s sitting beside you: “Excuse me, perhaps I’m crowding you a little?” and he’ll move back a bit and say: “No, praise God, I’ve got plenty of room,” thus giving you more space!’)

The second layer of the party-crasher is a comment on the value of hospitality. A good host would never act the miser and turn away a hungry reveller, whether the unexpected guest is known to him or not. True, this value of hospitality fit more easily in the ‘good old days’, when the harsh and simple life of the desert demanded that the Arabs help and feed one another to survive. It was a less comfortable fit in the multi-religious, multi-ethnic, trickster-and-thief-ridden party city of Baghdad. But, after all, the prophet Muhammad himself helped hungry uninvited guests gain entry to a feast. So the moral imperative is clear: the host must be generous and open-handed.

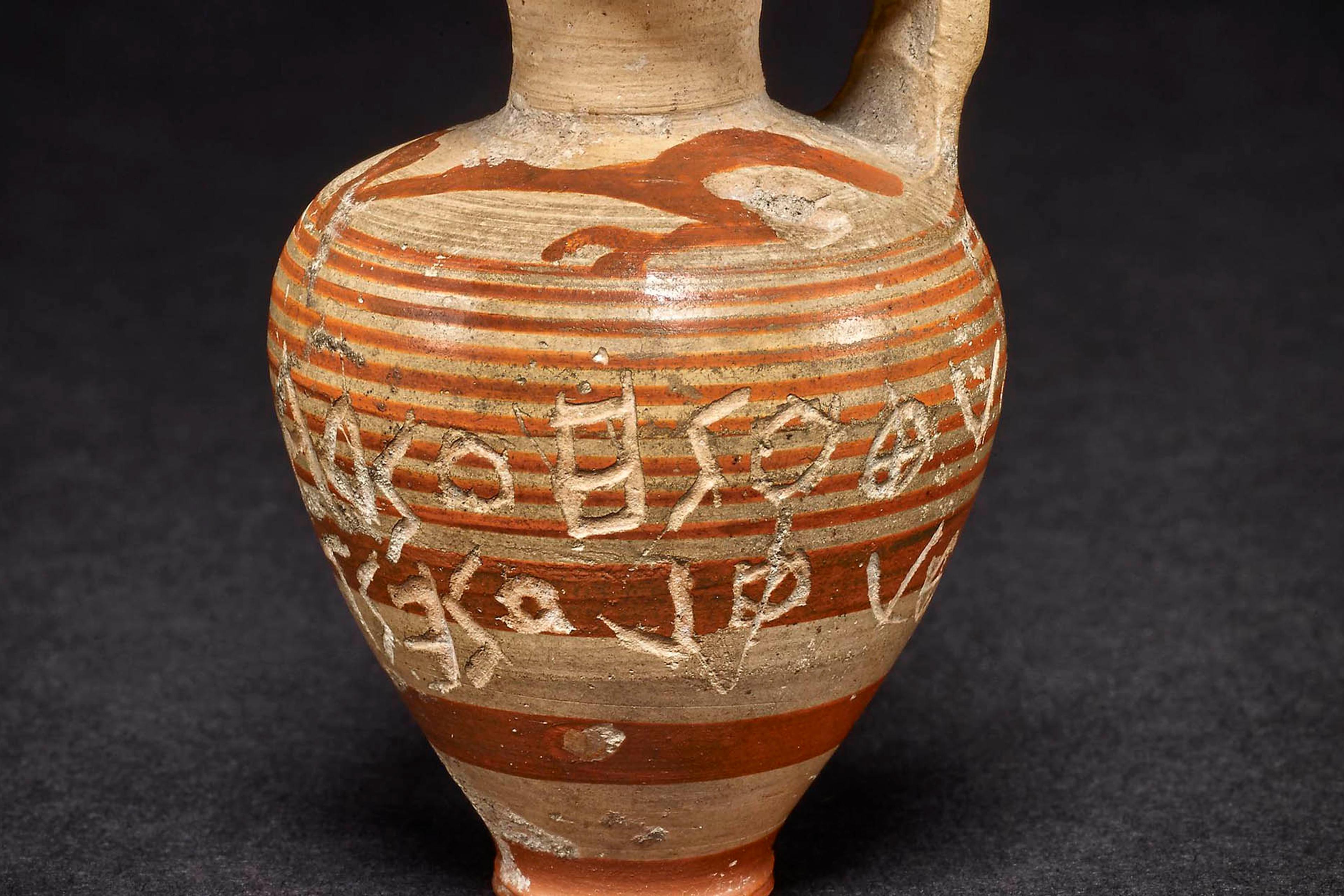

In fact, al-Khatib al-Baghdadi (whose name means ‘the Baghdadi preacher’) is famous not for his efforts compiling party-crashing anecdotes, but as a scholar of the transmission of hadith (the deeds and sayings of the prophet Muhammad). Before he gets into the really silly stuff in his book of party-crashing, he relates hadith reports in which the prophet proves himself a friend to the uninvited guest. Well before the arrival of Islam, moreover, cultures around the Mediterranean highly valued hospitality. The party-crasher exploits the privileged place of the guest in Greek literature as well; Plato’s Symposium is partly narrated by a party-crasher. Medieval Arabic literary banquets develop and play with many of the themes dear to their ancient predecessors – and they are just as wine-soaked as the Greek symposium.

The third layer makes the party-crasher into a metaphor for a varied range of purposes. For example, he might represent ‘new money’: someone who uses their eloquence to rise up from the gutter and talk their way into the most luxurious of feasts. Or the party-crasher might represent one whose beliefs you judge to be beyond the pale, and whom you might therefore exclude from your definition of orthodoxy. But, it is implied, really who are you to judge? I discovered this layer along with the realisation that one of the anecdotes in al-Khatib al-Baghdadi’s Tatfil, implausibly presented there as a true story, reappears as pure fiction in the collection One Thousand and One Nights.

Both tales tell of a party-crasher who, mistaking a prison boat for a pleasure cruise, sneaks on board looking for a good time, only to find himself threatened with execution alongside the criminals he has foolishly joined. In al-Khatib al-Baghdadi’s version, these ‘criminals’ are heretics, but the presence of a party-crasher among them is meant to suggest that excluding people from the ‘party’ of orthodoxy is an act of spiritual miserliness. In the One Thousand and One Nights, it is a nosey, over-talkative barber who acts as the party-boat crasher, and finds himself chained to a group of condemned bandits. But he talks his way out of his punishment, and eventually into the court of the caliph himself. This demonstrates the ‘new money’ theme, since a barber is of a lowly profession, but with pretensions to the lofty status of a qualified doctor. An eloquent barber is therefore well positioned to talk his way into high society, at least according to the logic of medieval Arabic literature.

The fourth layer is mystical; the party-crasher is a Sufi. In the stories, Sufis are (perhaps mockingly) credited with knowledge of the unseen:

If deep beneath the Byzantinian soil

pots are hot or dinner’s on the boil

you, from China, quickly come a-riding …

You always could divine where pots are hiding!

Some critics of the Sufis satirised them as spongers and tricksters – the kind of people who might weasel their way into a party for a free meal. On the other hand, a holy man might willingly adopt such a guise for his own mysterious purposes. Is the conflation of the Sufi with the party-crasher the result of the ‘Sufi’s’ dishonesty when he pretends to be on a holy path so that you are more inclined to feed him treats? Or does his apparent hedonism mask a deeper spirituality, a knowledge of the unknown, that allows him to cross over boundaries and walls, and to divine, impossibly, what you dreamed last night of having for breakfast today? This kind of party-crasher has the aura of a ritual clown.

This layer became clear to me as I dived deeply into another 11th-century Arabic work of party-crashing, Hikayat Abi l-Qasim (‘The Portrait of Abu l-Qasim’). This tells the tale of the Baghdadi party-crasher named Abu l-Qasim, who arrives uninvited at a party in Isfahan dressed and behaving like a holy man, but who goes on to drink to excess, dance, vituperate and flirt with male and female servers alike, before resuming his pious demeanour and garb at the break of the following day. An uncharitable reading of this character would paint him as a simple hypocrite or conman, whose holy appearance is only a flimsy disguise. A deeper reading might acknowledge him as a holy man and a sinner all in one, for the tale is meant to demonstrate that man as microcosm contains many contradictions.

And, finally, paradise itself is like a party: and you, perhaps, the party-crasher. Our sinful debaucheries on Earth are its mirror image. The caliph ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab, the prophet’s father-in-law, is said to have remarked that wedding banquets have ‘a pinch of the food of Paradise mixed in’. In paradise, you drink and eat, lounging in beautiful company in lush gardens. But do you really deserve to be there, or is it only that God is truly the most generous of hosts? So the fifth layer is the stuff of gods. Might this ragged wanderer knocking at your door be God himself calling in the guise of a beggar? You should let him in, if you wish him to return the favour someday. And then, as with Philemon and Baucis – pagan forebears of the generous Muslim host – your house might be transformed into a temple, if only you open your poor heart to those two tramps, Zeus and Hermes, the divinity in disguise.