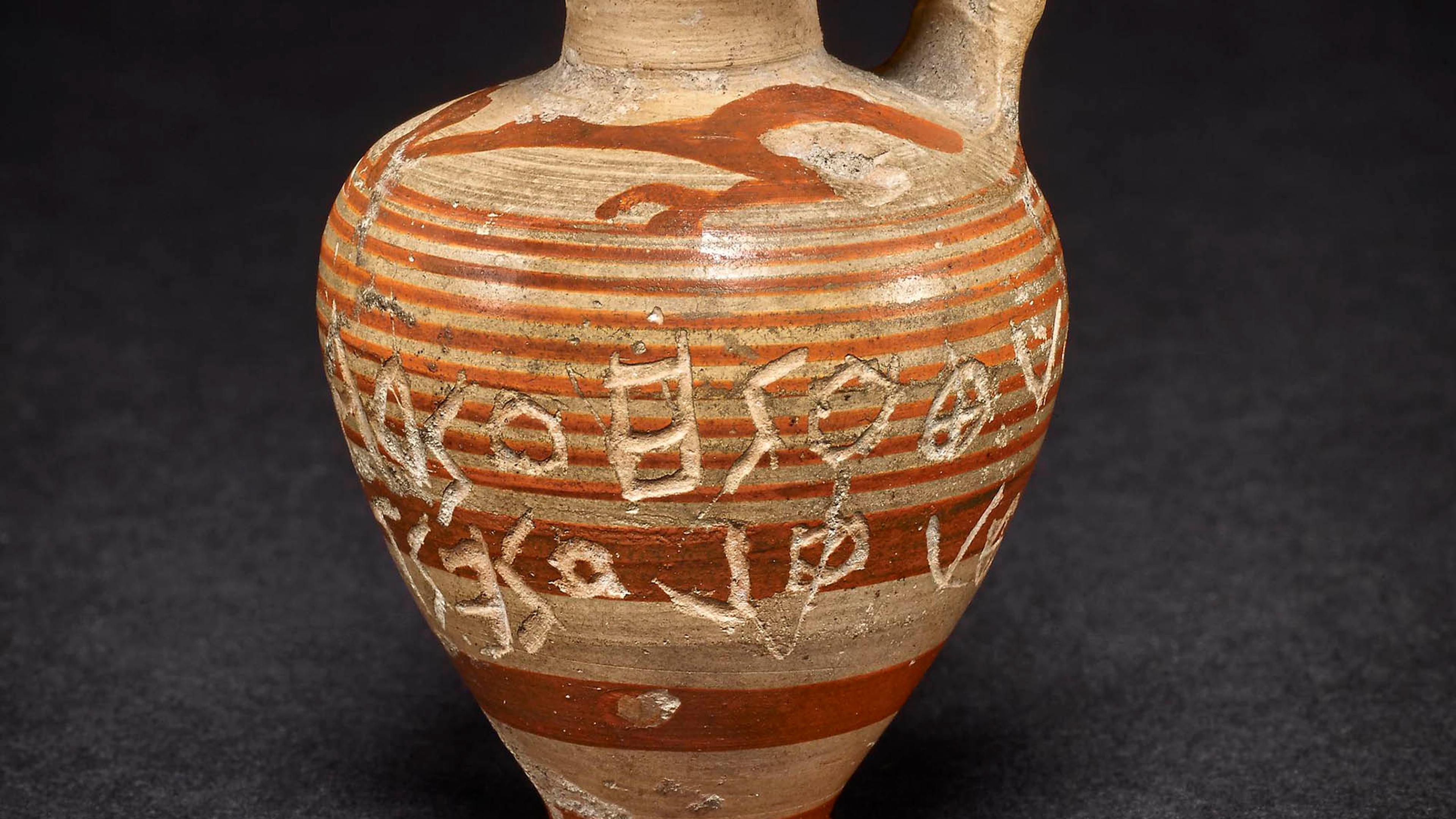

‘I am the kylix of Korax’ – so read the Greek letters, proceeding from right to left, which are inscribed on a shallow cup used to sip wine. It was found on the Mediterranean island of Rhodes and dated to the late 8th century BCE. Ancient Greeks had only recently adopted the Semitic writing system used by seafaring Phoenicians and adapted it to their own language. Certain aspects of this new technology were still being worked out – they had not yet settled on the direction in which they wrote, as our kylix shows – but one remarkable feature of this early specimen of Greek writing was already a convention: it spoke for itself, in the first person.

Among the earliest Greek inscriptions, such speaking objects, as they are known, bulk large: ‘Nikandrê dedicated me to the far-shooting goddess who rains arrows,’ declares a statue on the island of Naxos; ‘I am the lekythos of Tataie,’ an oil flask from a Greek colony near modern Naples asserts (issuing a warning to boot: ‘whosoever steals me will go blind’); and a shelf of rock in the Attic countryside proclaims: ‘I am the remembrance of Ergotimos.’ Surprisingly, no such convention is to be found among the Phoenicians or other Semitic cultures with which Greeks came in contact in the Mediterranean. The fact that it is nevertheless attested throughout the far-flung Greek-speaking world at the dawn of alphabetic literacy suggests that its interpretation requires us to situate it within the culture in which it took root.

We must imagine a world in which writing is new, in which it is unclear what kind of conventions govern written communication. In such a world, the use of the first person would have allowed the novel technology of writing to simulate the most fundamental form of communication in an oral society: conversation. Numerous epitaphs, through their use of the second person too, suggest that this was their author’s intent. Consider an epitaph composed by the poet Simonides in honour of the celebrated 300 Spartans slain in the battle of Thermopylae in 480 BCE:

O stranger, report to the Lakedaimonians that here

we lie, obedient to their words.

While this inscription seeks to engage passersby in conversation, a different 5th-century BCE inscription presents itself as answering their questions:

To all people I answer the same, whoever asks

which man dedicated me: Antiphanes, as a tithe.

Objects employing the first person to identify humans with whom they were associated would easily be interpreted, then, as messengers, ventriloquising them in their absence.

Such a posture can be found in the earliest extant Greek letter, a lead sheet from Berezan in present-day Ukraine, an island in the Black Sea which was colonised by the Greeks in the 7th century BCE. A century later, a man named Achillodorus sent his son an urgent missive, which may be translated as follows:

Protagoras, your father sends instructions to you. He is being wronged by Matasys, for he is enslaving him and has deprived him of his cargo-carrier. Go to Anaxagoras and tell him the story, for he [Matasys] asserts that he [Achillodorus] is the slave of Anaxagoras … (translation by Paola Ceccarelli)

Here too we find the author constructing his message in such a way as to simulate the speech of a messenger. Interestingly, the model of messenger underlies much of early Greek literature. Take the opening of the Iliad: ‘Sing, goddess, the anger of Peleus’ son Achilleus.’

The story of Achilles is not presented here as Homer’s; Homer is merely the mouthpiece of the Muse. The Odyssey is similarly set in motion by the singer’s appeal to the Muse to tell him of ‘a man of many devices’. The 5th-century lyric poet Pindar sings: ‘me, as her chosen herald of wise words, the Muse has appointed for Greece.’

But there is a problem. Pindar’s staggering skill would have convinced his audience that, indeed, he was blessed by the gods, but why should anyone believe an Italian oil flask that it belongs to a woman named Tataie, not to mention the threat that its thief would go blind? On what authority could the flask make a legal claim, even if we should not imagine it to be made entirely seriously?

As we might expect in view of its novelty, the authority of writing was a problem in Greek culture. Nowadays written documents are usually understood as more dependable than fickle humans, but, for centuries after writing’s inception, it was the other way around: oral testimony was considered more reliable than a written record. In contemporary literature, writing was likened to a helpless child. In Aristophanes’ comedy Clouds, the figure of the author speaks of a play he composed but didn’t produce as being like a child he was forced to abandon. In Plato’s dialogue Phaedrus, Socrates warns his eponymous interlocutor that a written text ‘needs the support of its father’. If it is criticised, he explains, it will not be able to stand up for itself.

No one was better placed to speak of the legal status of the oil flask or kylix than the objects themselves

In order to understand how these early texts set out to establish their authority, it is instructive to return to the beginning of the Iliad, which we have seen to be unexpectedly related to Tataie’s humble oil flask:

Sing, goddess, the anger of Peleus’ son Achilleus

and its devastation, which put pains thousandfold upon the Achaians,

hurled in their multitudes to the house of Hades strong souls

of heroes, but gave their bodies to be the delicate feasting

of dogs, of all birds, and the will of Zeus was accomplished

since that time when first there stood in division of conflict

Atreus’ son the lord of men and brilliant Achilleus.

What god was it then set them together in bitter collision? (translation by Richmond Lattimore)

Homer assumes the role of a messenger because he presumes to tell his audience a story from a long-ago past, one in which gods and goddesses mixed with humans, far removed from their own reality. It is only with the help of the Muses that he can answer the question posed above (the answer: Apollo), or later recite a lengthy catalogue, more than 250 hexameters long, of all the ships that set sail for Troy:

Tell me now, you Muses who have your homes on Olympus.

For you, who are goddesses, are there, and you know all things,

and we have heard only the rumour of it and know nothing.

Who then of those were the chief men and lords of the Danaans? (translation by Lattimore)

Homer worked to establish his authority in other ways, too. Narrating the apparently dry catalogue of ships was, in fact, a delicate affair; the Athenians were later accused of tampering with the text in an attempt to establish their historical claim to the neighbouring island of Salamis. It is therefore important – and not incidental – that nothing about Homer’s personal circumstances can be gleaned from his poetry. He is a man without qualities, which allowed multiple Greek cities to lay claim to him, and all of them to identify with his work. It is because he achieved Panhellenic status that the catalogue was used as historical evidence in the dispute over Salamis.

Homeric poetry drew on venerable oral traditions, and certainly was not designed for readers, but the strategies of authorisation he employed offered themselves to early writers faced with the problem of crafting messages which did not require ‘paternal’ support. Like Homer, the authors of our speaking objects put their words in the mouths of more commanding authorities: the objects themselves. As the expertise of the Muses, daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne (‘Memory’), with regard to the past was unquestionable, so too no one was better placed to speak of the legal status of the oil flask or kylix than the objects themselves. Korax’s kylix was not, after all, simply the medium of its owner’s message, but also its subject. They were able to inspire greater confidence because, like Homer and other messengers of the Muse, they were reliably impartial. It is no mere pun to say that their object-ivity granted them the authority that interested human parties could never have.