Having close relationships is one of the most consistent predictors of happiness. Psychologists often recommend prioritising relationships in order to live a happier life. And yet, the data on relationships and wellbeing present a puzzle: people who live in places where relationships tend to be more stable are not necessarily happier. For example, despite the fact that countries such as the United States and Sweden have higher divorce rates than other countries, people also report being happier there than in many other places around the world. People in collectivistic cultures typically describe relationships as more important than people in the US do, but in many cases they are less happy.

What gives? For a clue, consider something that the US psychologist Glenn Adams observed while living in Ghana. He kept seeing bumper stickers that warned people to be careful about their friends. One sticker read: ‘I am afraid of my friends. Even you.’ Next to the warning was a menacing cartoon finger pointed at the reader. Adams was intrigued. Was this a fringe idea or something that many people in Ghana felt? He ran a simple study to find out. He asked college students in the US and Ghana if they had enemies in their social circle – ‘people who hate you, personally, to the extent of wishing for your downfall or trying to sabotage your progress.’ The results echoed the bumper stickers: in Ghana, 79 per cent said they had an enemy; in the US, it was just 17 per cent.

As more psychologists looked into it, they found this wasn’t just a story about Ghana. For example, students in Hong Kong were more likely than Americans to agree with statements like ‘I am the target of enemies’ and ‘People who claim they do not have enemies are naive.’ Another study found that Canadians largely disagreed with these statements, like most of the Americans did.

When Adams asked people to tell him more about perceived enemies, he found that Americans often mentioned leaving such individuals behind. One participant told him: ‘I cannot quite understand … why one would continue to interact with somebody who one did not like.’

This quote hints at a concept that we and our colleagues have explored in our own research: relational mobility. The idea is that some cultures have more flexible relationships than others. That is, people within these cultures have greater freedom to choose who they want to be around, and to leave relationships with people they don’t like. Other cultures have lower relational mobility. In these cultures, relationships are more stable and long-lasting. People’s social connections are secure, but they have less choice in those relationships. Even if they’re unhappy with their relationships, they tend to stick with them.

The freedom in relationally mobile cultures extends across different types of social connections. People in these cultures meet more acquaintances, have more romantic partners, get divorced more, and change jobs more often. The mobility is sometimes just about changing who they associate with, but sometimes it’s physically packing up and leaving town. Relationally mobile cultures have higher rates of people literally moving.

Courts in the Philippines and India do not allow a husband or wife to unilaterally file for divorce if there is no one at fault

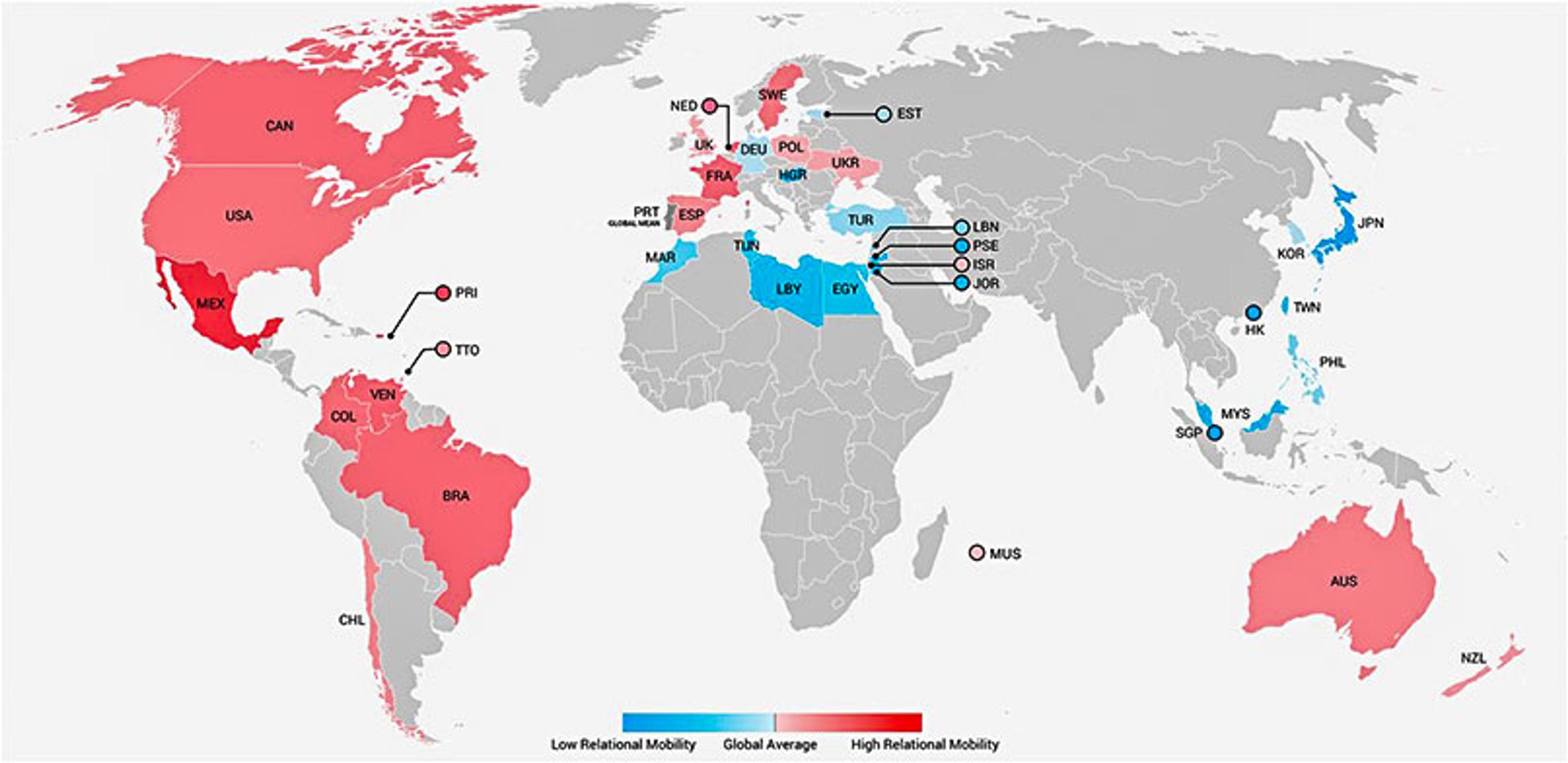

In a study that measured relational mobility in 39 cultures around the world, one of us (Thomas Talhelm) and his colleagues surveyed about 17,000 people. The participants in this research rated their levels of agreement with various statements about what it’s like to start and end relationships in their society – eg, that it’s easy for one to ‘meet new people’, or that people ‘often have no choice but to stay in groups they don’t like.’

People in certain countries, including Brazil, Mexico, Sweden and the US, indicated that relational mobility was the norm. In other countries, such as Egypt, Japan and Malaysia, people said that relationships were more fixed.

Relational mobility society-level latent means in visual format. Blue indicates societies lower in relational mobility than the midpoint (Portugal). Red indicates societies higher in relational mobility than the midpoint. Courtesy relationalmobility.org

We were measuring people’s perceptions of their social environments – the unwritten rules about relationships. But cultures also have explicit rules that shape relational mobility. For instance, courts in the Philippines and India do not allow a husband or wife to unilaterally file for divorce if there is no one at fault. Meanwhile, in Japan, renting an apartment often requires the tenant to pay fees equivalent to three months’ rent that they will never get back. This is a strong disincentive to moving apartments every year.

The previous findings on ‘enemyship’ suggested that having the flexibility to ditch relationships with certain people – especially those you don’t like, or who don’t like you – might be good for wellbeing. While people in cultures that offer such flexibility might have relationships that are less stable over time (including higher rates of divorce, as in the US and Sweden), they also have the freedom to leave unhappy relationships and a greater opportunity to meet new people.

This sort of relationship ‘free market’ might allow people to sort into more emotionally satisfying relationships, bringing out more positive relationship habits. For example, people in relationally mobile cultures are more likely to say that they tell their close friends their secrets, like their failures and their worries. Studies have found that this sort of self-disclosure tends to bring people closer together. People in relationally mobile cultures also tend to say that their interests and hobbies are more similar to those of their friends, and that they trust people more. These findings on trust fit with the suspicion that people reported in Ghana, and with how many US participants found it hard to even understand how someone could have an enemy in their life.

Our research team – which also included Alexander Scott English, Yan Zhang, Xuyun Tan, Jiong Zhu and Junxiu Wang – recently tested this idea, comparing relational mobility scores around the world with surveys of happiness. Sure enough, people in cultures where relational mobility was higher also tended to report higher levels of wellbeing.

We found that people in the more relationally mobile Chinese prefectures tended to be happier

Of course, one difficulty with comparing countries around the world is that there are lots of other differences between places like Sweden and Japan. Relational mobility is one difference, but Sweden also has a different religious history, climate and culture of work-life balance. We can – and did – use statistical methods to account for potential confounding factors such as economic development, inequality and education. But we’re limited to the factors for which we have good statistics.

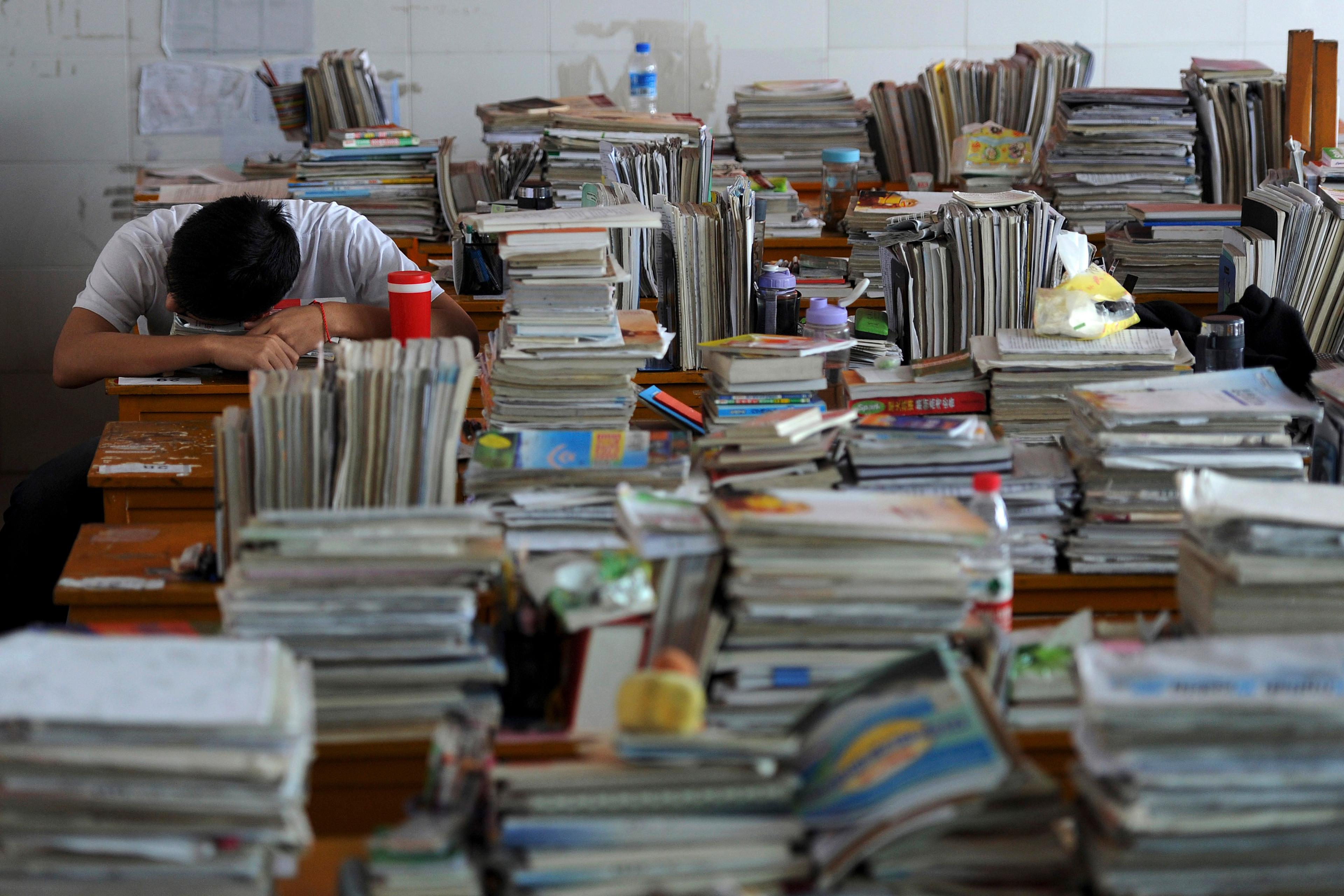

One way to get around all the factors that differ between countries is to compare regions within the same country. To do that, we teamed up with researchers at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences in Beijing to survey more than 22,000 people across 328 prefectures in China. Participants told us about the relational mobility where they live, as well as personal details such as income and education. They also told us how happy they were by indicating their level of agreement with a few simple statements, like: ‘On the whole, I am a happy person’ and ‘In most ways my life is close to my ideal.’ As with the findings from around the world, we found that people in the more relationally mobile Chinese prefectures tended to be happier.

What about the question of cause and effect? We want to know whether relational mobility actually makes people happier, but we can’t wave a magic wand to change cultures around the world and see what happens. The world isn’t our lab. As a next-best option, however, we can track people over time and see if changes in relational mobility precede changes in happiness. There’s a parallel to the limits on smoking research. It’s unethical to force people to smoke to see if they get lung cancer, so epidemiologists have relied on tracking people’s smoking and health over time to see if smoking tends to precede cancer diagnoses.

We did this with relational mobility, surveying college students at 13 universities around China. Some of these students moved to universities in prefectures with high relational mobility. Some moved to prefectures with low mobility. Moving to college is a time of adjustment: people are trying to fit in, and it’s common for students to experience depression and anxiety. We suspected that the adjustment would be easier for students who moved to more relationally mobile communities.

When they had just arrived at their university, students in more mobile prefectures were slightly happier than students in less-mobile ones. But over the next three years, we found, this happiness gap widened significantly. The study also gave us insight into one reason people are likely to be happier if they move to places where there is greater relational mobility. Students in these environments said it was easier to make friends – and their reports of making new friends predicted increases in happiness. Short of a magic-wand experiment, this study gives us compelling evidence for the idea that relational mobility makes people happier.

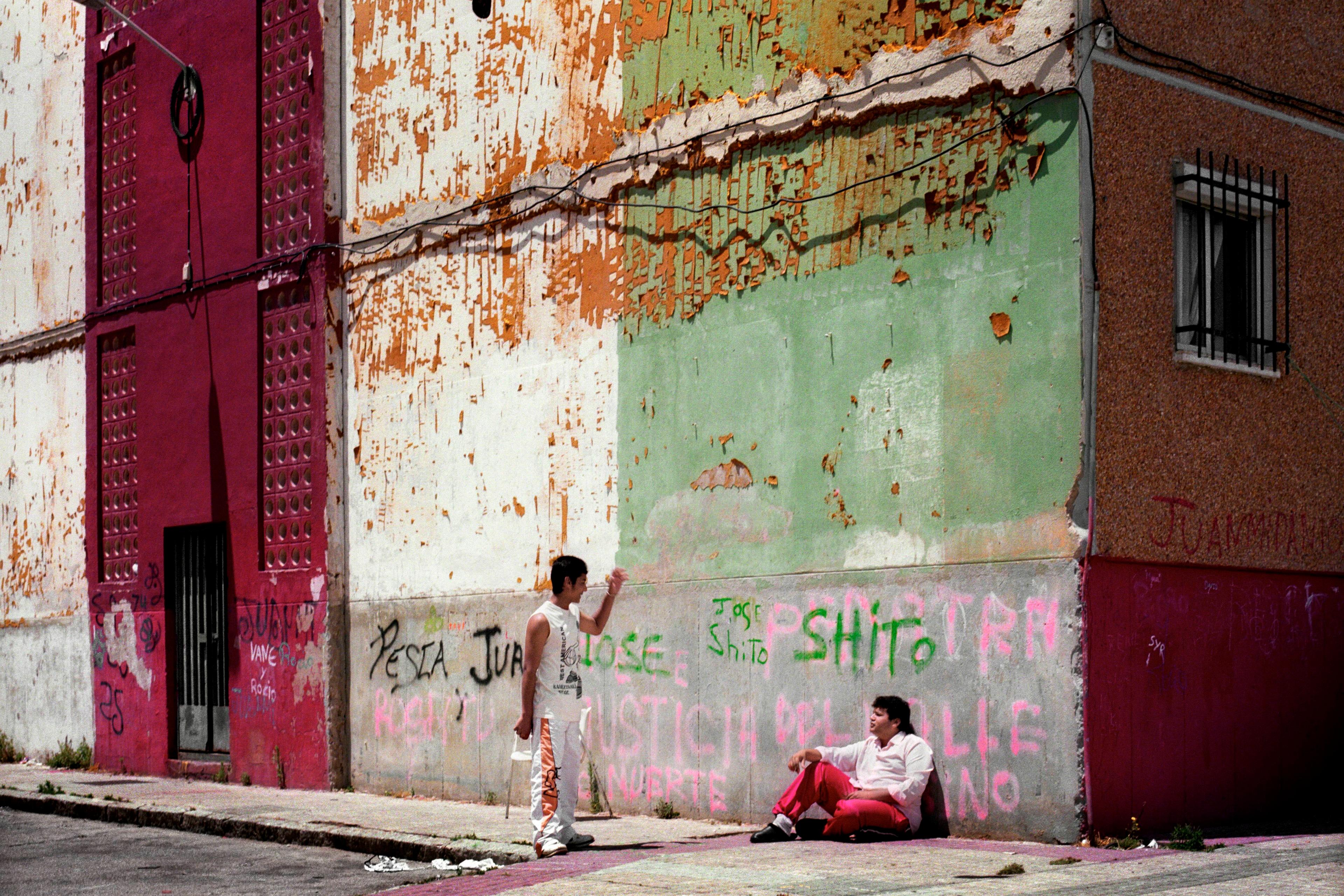

If relational mobility does increase wellbeing, that raises the question of why there are low-mobility cultures in the first place – and whether low mobility is some kind of cultural defect.

We think not. Cultures with lower relational mobility tend to appear in environments that are more threatening. For example, they have higher rates of disease, warfare and natural disasters. This suggests that having fixed, stable relationships might help people get through challenging times.

Low relational mobility seems to be adaptive for linking people together to overcome challenges

Another finding that suggests a functional side of relational fixedness is that it’s common in cultures with a history of rice farming, as in Korea and the Philippines. Rice farming isn’t a threat, like an earthquake or war. But it has historically required more labour and coordination than farming crops like wheat and corn. Paddy rice farming was built around irrigation networks that farmers had to manage together. In that sort of system, people needed to rely on each other to put food on the table. The fixed relationships of low-mobility cultures probably helped farmers cope with the demands of rice farming. A culture in which relationships were more fixed would mean that farmers knew they had people to rely on, even if they didn’t always like or even choose their social ties.

Our research suggests that low relational mobility is not a disorder; it seems to be adaptive for linking people together to overcome challenges. But its function is not to make people feel happy, at least not in times of safety.

What we’re learning about relational mobility and wellbeing might prompt you to consider your own experience: do you feel stuck with social ties that make those pessimistic bumper stickers in Ghana seem like useful advice? Cultural differences in relational mobility are partly objective reality – mobile places have more people moving homes and more Meetup.com groups. But the differences are partly in our heads. They’re in our beliefs about whether we could leave, and how it would go if we tried to meet new people.

Those beliefs about meeting new people aren’t always accurate. One study, for example, found that encouraging riders on a commuter train to talk to a stranger made them feel happier – contrary to their expectations. For those of us who are interested in adding a bit more mobility to our social lives, it could begin simply with believing that it’ll probably make us happier.