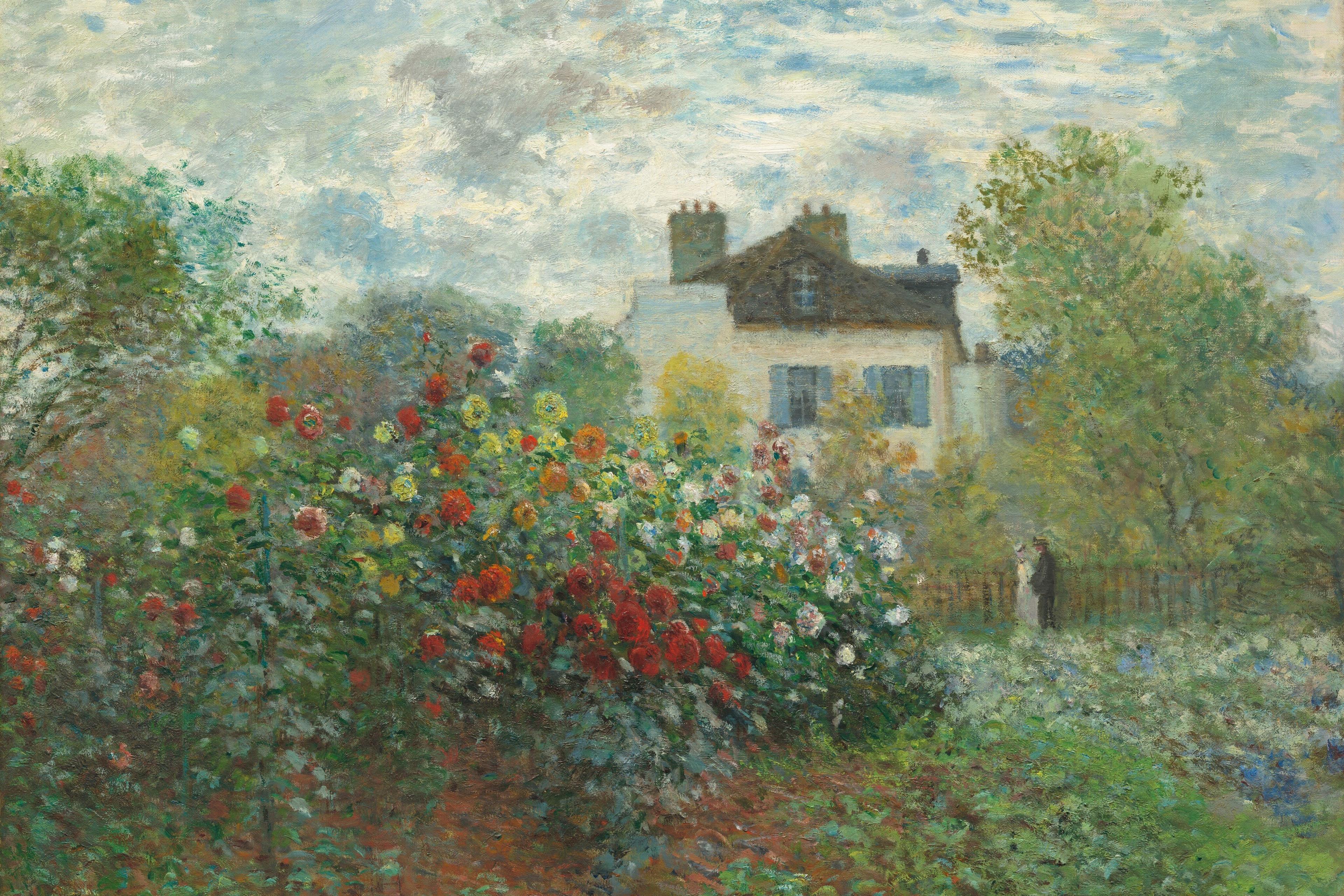

Two young men sit facing each other on a marble terrace. They are wearing elegant robes in pastel shades and delicate floral patterns, matching turbans, and finely worked daggers tucked prominently into the sashes at their waists. The one on the left, evidently the host, also boasts a light-green, gold-embroidered overcoat with a fur collar and a black aigrette adorning his turban. He reclines against a large bolster of gold fabric with a pattern of pink damask roses, and is being fanned by a younger attendant with a peacock feather fan. The two men are looking at each other intently, just a hint of a smile playing around their lips.

This quietly luxuriant scene appears in a 17th-century painting from Mughal India, now held at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston under the title ‘A Prince Having Audience’. It is just one example, though perhaps an especially fine one, representing an enormous corpus of similar South Asian genre paintings of elite figures lounging or conversing on garden terraces.

A mainstay of early modern Indian painting, such works were produced across much of the north and centre of the Indian subcontinent throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. And, like many of these pieces, the image of the young gentlemen’s meeting is endowed with a sensory dimension that goes beyond what can be physically captured by paper and paint. Though it may not be readily apparent to most present-day viewers, fragrance is in fact central to the work; multiple layers of meaning are conveyed through the strategic inclusion of key scented flowers in the picture. There are the aforementioned pink damask roses ornamenting the gold fabric covering the bolster and, on the floor between the two young men, alongside an ornate sword, sits a small blue bowl filled with white jasmine buds. More importantly, however, both of them hold finely drawn narcissi stems up to their faces, ready to inhale the blossoms’ heady perfume.

Together, this trio of flowers constitutes a sort of short-hand summary of the garden setting that is otherwise only hinted at by the marble terrace, the railing and the hazy blue background. Take, for instance, a verse by the prolific Urdu poet Valī Muḥammad ‘Naz̤īr’ Akbarābādī (1735-1830), which succinctly sketches a generic rich person’s garden as:

Narcissi, wild roses, and jasmine are blossoming in the garden beds

There are a pool, fountains, and reed screen curtains in the pavilions, too.

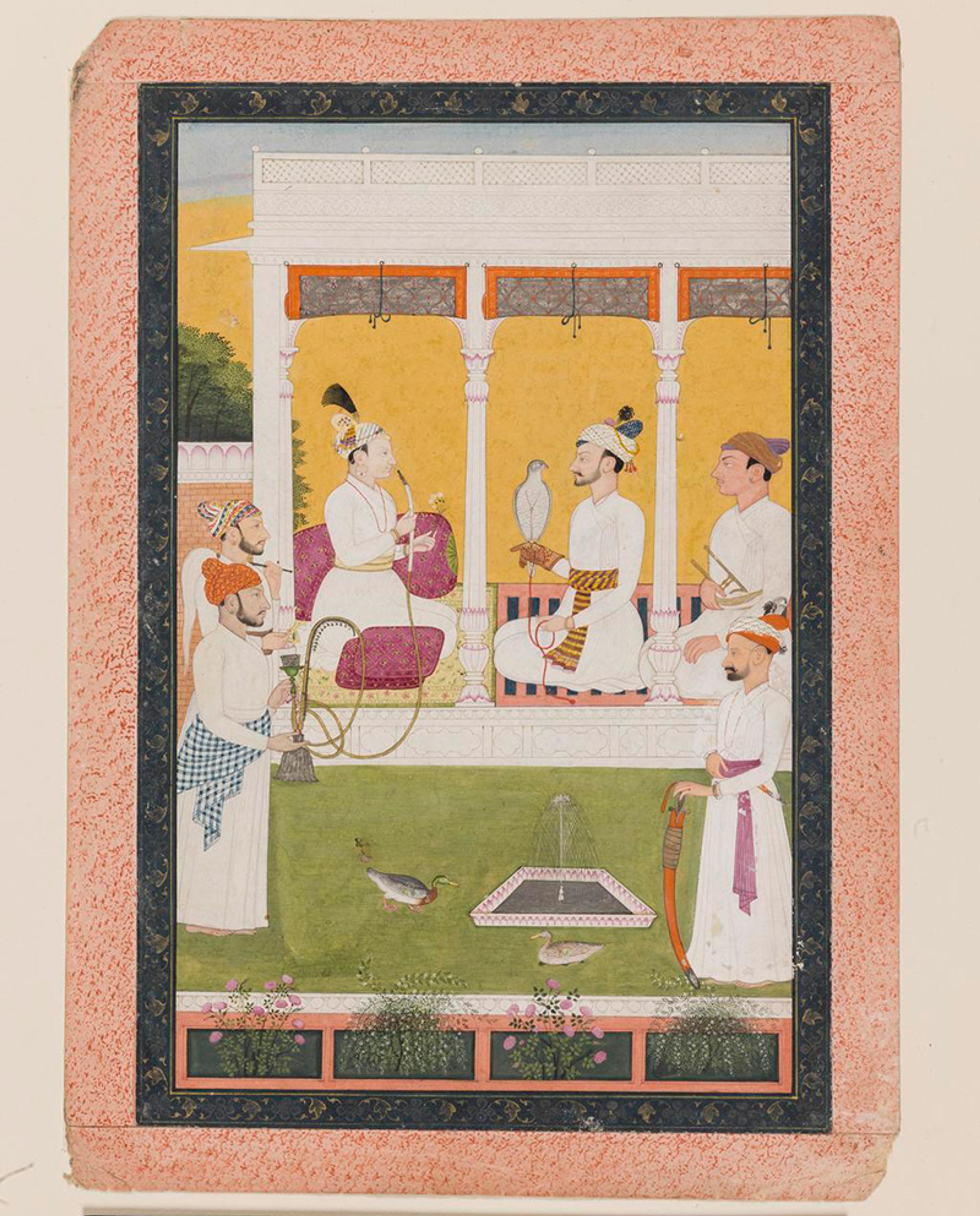

Notably, the flowers here are the same that accompany the young men; they are also the same as those featured in another painting produced in the Himalayan foothills and dated to around 1785, now at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. It shows Raja Bhup Chand of Bhadrawah (Bhaderwah) seated in an arched veranda overlooking a garden, surrounded by courtiers. Like the two gentlemen in the painting at the MFA, he is holding a narcissus sprig, while pink-flowered damask rose-bushes and delicate, vining jasmine shrubs alternate in a flowerbed that runs across the bottom of the image.

Raja Bhup Chand of Bhadrawah, Pahari (Chamba) (c1785) © Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, UK

Yet beyond this culturally conditioned evocation of an intensely fragrant garden, the narcissi in particular carry additional associations that sophisticated viewers were meant to pick up on. Narcissi, specifically varieties of the Mediterranean species Narcissus tazetta, long cultivated and naturalised across much of Asia, are traditionally likened to eyes in Persian literature, due to their circle of white outer petals surrounding a round inner cup reminiscent of a pupil. By extension, they allude to vision more broadly, representing flirtatious looks and amorous glances. Countless verses in Persian and Persian-influenced languages such as Urdu play on this; take, for instance, this couplet evoking the sexual tension in a lovers’ quarrel by the Delhi poet Shaikh Muḥammad Ibrāhīm ‘Zauq’ (1790-1854):

Hamen nargis kā dastah ghair ke hāthon se kyon bhejā

Jo ānkhen hī dikhānī thīn dikhāte apnī naz̤ron se

Why would you send me a bouquet of narcissi at the hands of my rival?

Whatever fight you had to pick with me, you could have done so with your glances!

The poetic conceit here hinges not only on the equation of the narcissi with eyes, but also on the Urdu idiom rendered here as ‘to pick a fight’ since it literally translates as ‘displaying eyes’. Narcissi as cut flowers were part of the politics of social and romantic exchange. In about 1745, the scholar and courtier Ānand Rām Mukhliṣ (1699-1750) wrote the following about the double-flowered ‘Constantinople’ or ‘Double Roman’ cultivar of N tazetta that:

it is like a [regular] narcissus except that it has less scent … The yellow of it, which ought to be like the pupil of an eye, was hidden in the petals and not expanded properly. Due to its rarity, it may be given as a gift.

In other words, the aesthetic value and cultural significance of the narcissus derived from its canonical eye-like appearance, its use as a fancy gift, and its scent. People considered the sweet-yet-sharp fragrance of N tazetta a natural mufarriḥ or ‘exhilarant’. Ṭibb-i yūnānī or ‘Greek medicine’, as the traditional Indo-Persian system of humoral medicine is commonly called, posits that such exhilarants ‘open up’ and strengthen heart and mind, and thus act as antidepressants and even aphrodisiacs, primarily on account of their aromatic qualities. The fresh, spicy, quintessentially spring-like scent of the narcissus constitutes a natural version of this – and as such appears in the painting of the two elegant youths. As a poetic reference to eyes and the act of seeing, the narcissi they hold reinforce the expectant gaze with which the two regard each other. At the same time, the implied act of smelling the blooms’ powerful fragrance suggests a quiet exhilaration, anticipating the romantic possibilities and additional sensual pleasures that lie ahead.

Narcissus tazetta ‘Avalanche’. Photo by Getty

Our research project and online exhibition Bagh-e Hind (2021) presents complex sensory stories such as these, which are encoded in the sumptuous yet far-too-often ignored minutiae of material culture in 17th- and 18th-century Indian painting. The title translates to ‘Garden of India’, and the virtual exhibit features a large array of Mughal and Rajput garden scenes from collections around the world, organised according to their genre conventions, as well as the flowers and other olfactants they highlight. The exhibition pairs these galleries of primarily 17th- and 18th-century paintings with photographic documentation of the specific types of plants, as well as the kinds of luxury objects they feature.

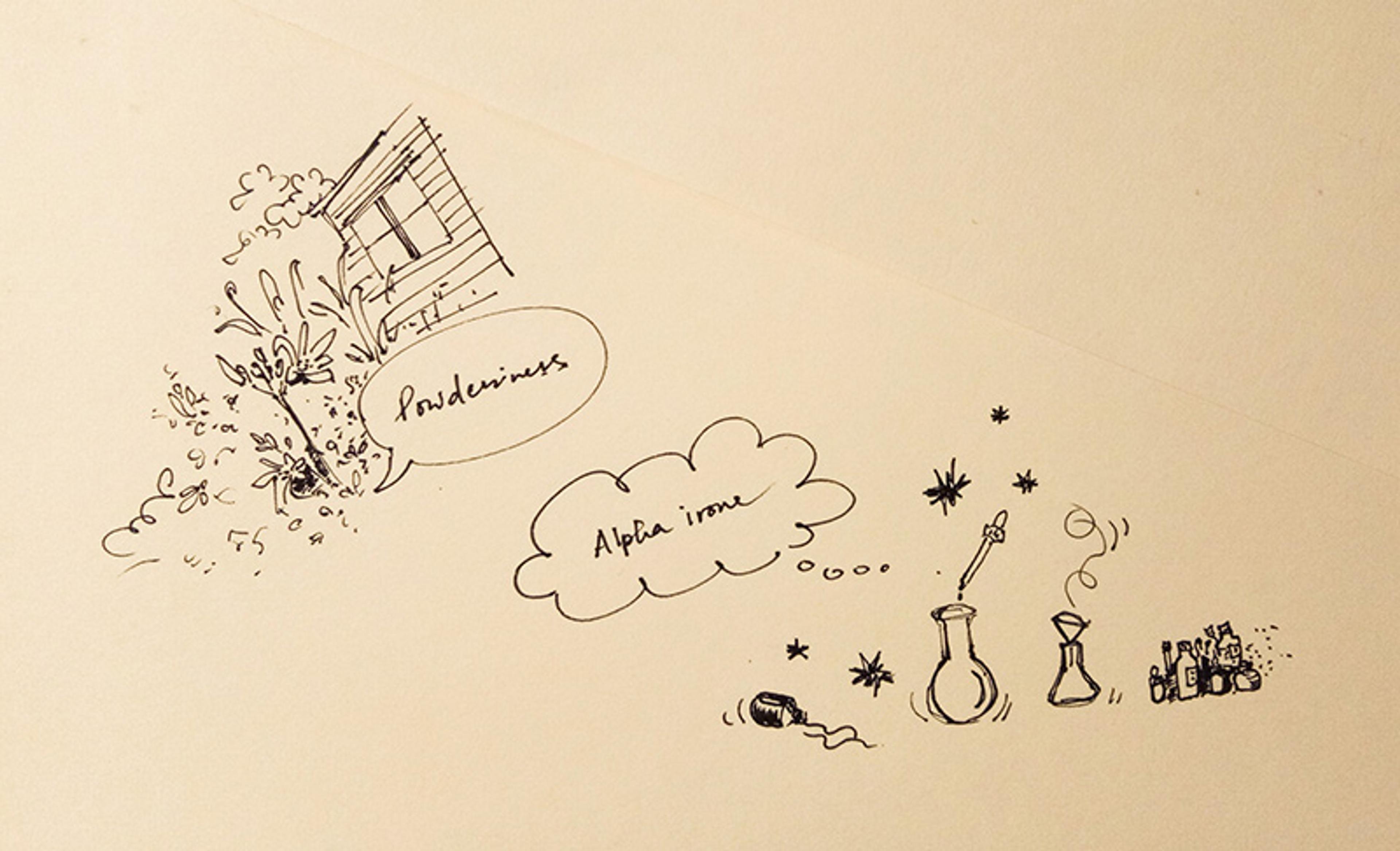

The process between the historian and the perfumer (2021), sketch by Bharti Lalwani, ink on paper

Bagh-e Hind offers perfume translations of one painting from each of our five scent genres: rose, narcissus, smoke, iris and kewra. Certain olfactive prompts in the paintings were not as straightforward as one might expect. As we communicated through virtual platforms between India and the United States, our olfactive vocabulary had to be precise. A painting depicting poppies meant ‘narcotic powderiness’ to the gardener-historian and ‘ionones’ (a group of synthetic aroma molecules) to the perfumer. If narcissus was described as having a ‘sweet spicy’ note, it was agreed that saffron extract could represent that facet well.

The perfume for ‘A Prince Having Audience’ burns particularly bright and hot. The painting possesses an atmosphere redolent with fragrant yet subdued tension, a moment heightened with possibilities – to enter it is to inhale its anticipation, love, desire. Its perfume-translation centres the narcissus, and we let the flower’s green, vegetal, sweet-spice and floral-faecal profile dominate. Narcissus fused with psychoactive blue lotus extract and heady jasmine represents the stillness between the gaze of the two men. Below the surface of propriety, etiquette and restraint, however, lurks the restless olfactory facet of lust supplanted by castoreum, civet and ambergris that attune the nose, eye and brain to the sensual details in this composition – the fur collar worn by the prince, the slow movement of the peacock feather fan, the feather in the aigrette.

An early draft of the Narcissus perfume-translation, composed by Lalwani

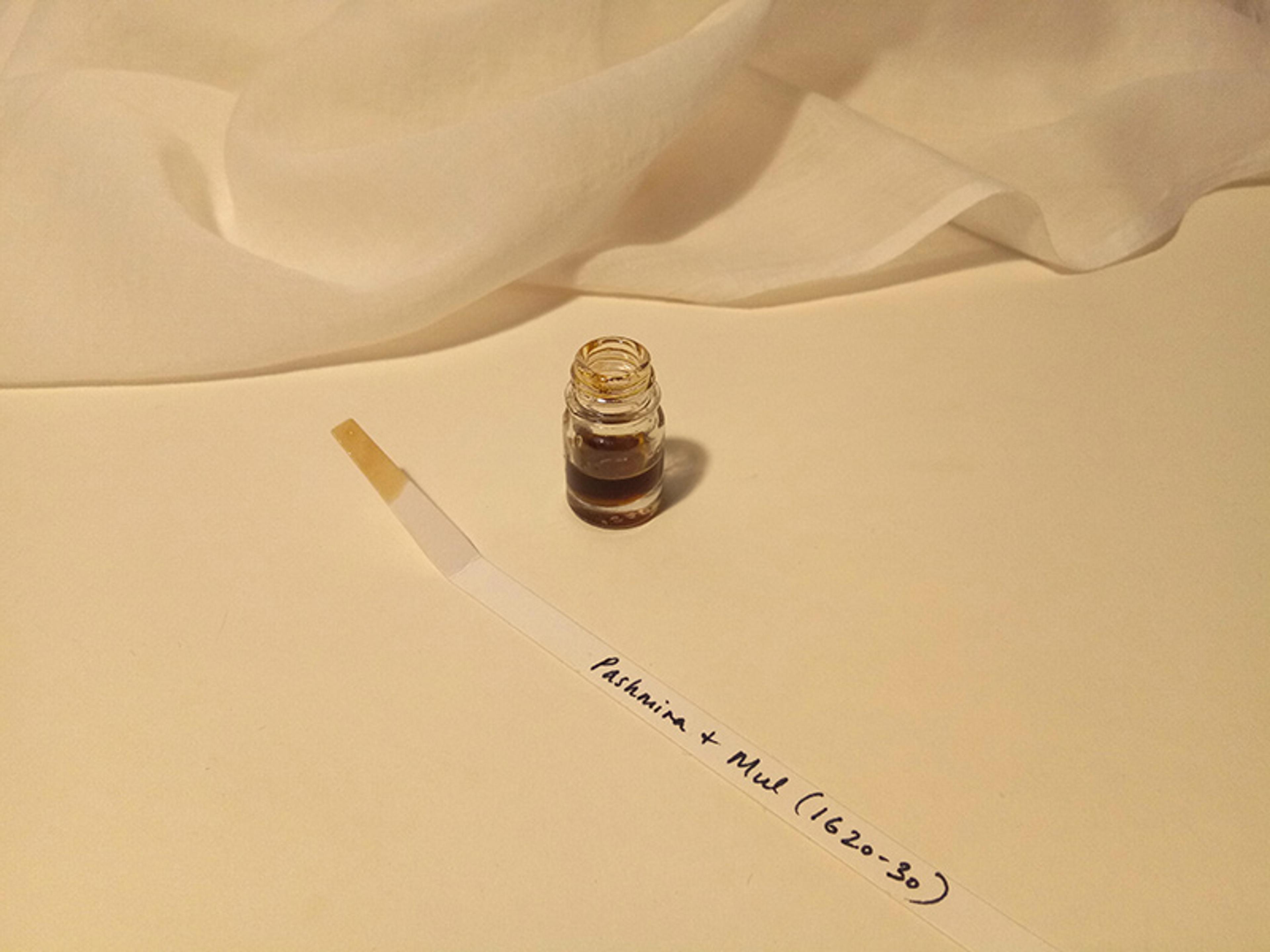

A pashmina and mul (cotton) accord that constitutes the olfactory core of the Narcissus perfume

The cashmere musk-accord in this perfume (musty, camphorous and metallic) also reinforces the sensuality of luxurious textiles that cover the bolsters, floor covering, and the garments – silks, cotton and wool embroidered with fine gold metal thread – adorning the men’s perfumed bodies, and the flash of lustrous daggers tucked in their sashes. Cool nuances of lotus, violets, lilies and jasmine yield to the hot-narcotic accords that hint at expectations of intimacy. We pair this painting with 18th-century Urdu poetry to add to the fantasy that evokes fragrant-floral seduction. Sirāj Aurangābādī (1712-64) declares in one couplet that the narcissus does not compare to the bashful glances of his lover. Another, Mīr Shākir Nājī (1690-1744), composes a verse to describe the beauty of a young boy – a red turban on his head, just like our prince, lips akin to a floral bud, he is perceived as the very embodiment of spring.

Formulating the edible perfume momentarily recreates a visual of the narcissus, with drops of yellow-ochre tuberose extract in jasmine-infused sugar, before thorough mixing. This perfumed sugar is then blended in with apricot compote and dried apricot pieces

Crafting the edible perfume recreates the delicate scent of narcissus flowers on the palate

Quiet scenes such as our two young men sniffing narcissi carried visceral and complex scents. One may look upon this painting and intellectually recognise its fragrant prompts, but it is the perfume – experienced in combination with the poetry, classical Hindustani music and other synaesthesic elements in our exhibition – that unleashes the full extent of its eroticism for the viewer. The edible perfume, one of the key components of our translations, entices with the possibility of tasting desire-as-floral-moonlight. To make it tenable to taste narcissus-as-lust, we combined extracts of tuberose, saffron and jasmine to blend into dried apricots. The gem-toned pieces of fruit simultaneously play with sight, taste and smell. One tastes the fleshy fruit – tangy, sour, sweet – but smells narcissus, amounting to a vision in their minds, of the yellow eye amid a cloud of floral lightness.

The Bagh-e Hind online exhibition seeks to take viewers into a garden of opulence, abundance and beauty by reuniting sensual, botanical, musical and intellectual culture of the time that expands one’s experience of South Asian art history that was not thought possible before. In our exhibition, we have made available not just the English translations of obscure Urdu poetry, but also our collaborative working notes and list of perfumery raw materials. As curator-gardeners, we continue to build a world of botanical and aromatic resources and reading lists for the general public who may want to recreate our fragrance and flavour translations, or reconstruct a garden and experience Bagh-e Hind even as the multisensory project lives and grows online.

‘Bagh-i Babur’ garden water feature reimagined by Lalwani as an octagonal shell and ‘water’, both composed of soap with the perfume of pashmina and mul