Have you ever noticed how someone who’s drop-dead gorgeous can also seem charming, honest and kind – even before they’ve said a word? That’s the halo effect, a common psychological bias where one trait (such as good looks) influences your impressions of someone’s other qualities. The halo effect was first systematically studied by the psychologist Edward Thorndike more than a century ago. In 1920, Thorndike reported that when he analysed the judgments of military officers evaluating their subordinates, their ratings of intelligence, leadership and physical qualities tended to blur together. If a subordinate excelled in one area, the evaluator was inclined to think he was exceptional in all of them. The effect shows up in many different fields, including social psychology, clinical psychology, child psychology, health, politics and marketing. The ‘attractiveness halo effect’ is what happens when a physically beautiful person also seems interesting, capable and good-natured. It’s as if we’re wired to judge books by their covers, even if we know we shouldn’t.

The halo effect isn’t confined to human traits, either. This cognitive shortcut shapes perceptions of everything from objects to organisations. One study examined how labelling a bottle of wine as ‘organic’ led tasters to rate its aroma and taste and their overall enjoyment more highly than the same wine without the ‘organic’ label. Marketing, politics, labels, branding and first impressions all tap into this bias, nudging us to think: ‘If one thing about this is good, or bad, then other things about it must be.’

Despite how common and powerful this bias is, scientists still don’t know exactly why it happens. Exploring this gap in understanding is crucial, because uncovering the foundations of our biases equips us with the knowledge to critically examine them and to develop better strategies to manage their impact. Early theoretical models of the halo effect attempted to frame how our evaluations get intertwined. These suggested, for instance, that having a general impression of someone shapes judgments of that person’s specific traits, or that one particularly salient trait sways judgments of other traits. While these models mapped out how the halo effect might happen, they can’t explain how to predict which traits will get lumped together.

To understand the halo effect better, we recently turned to the world of language and the power of computational models. As we’ll explain, these models offer a way to quantify the semantic association between words – including words for traits, such as ‘beauty’ or ‘intelligence’. This provides a potential method of understanding whether and why people expect two actual traits (eg, beauty, intelligence) to co-occur in the same individual. In short, we conducted two studies to explore the role language plays in generating and perpetuating the halo effect.

In our research, we employed word2vec, a word-embedding model. These models use a large amount of text – taken from books, articles and/or news sources – to analyse the context in which a word (such as ‘beauty’) tends to be used, which is then represented as a list of numbers, called a vector. The vectors we get from models like word2vec are very similar to those computed during the training of large language models such as ChatGPT.

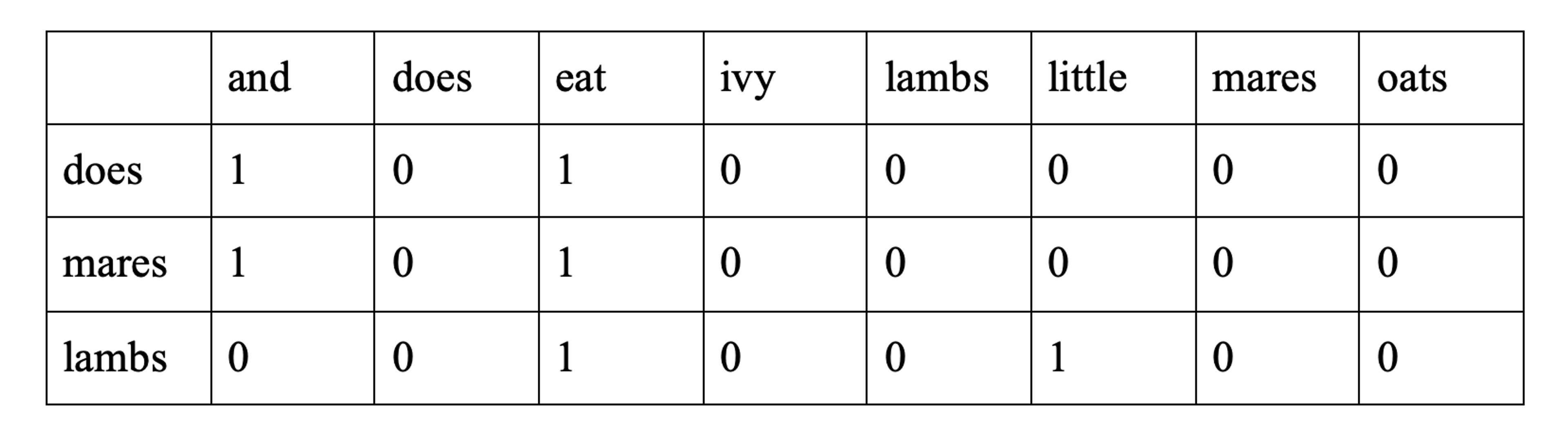

You can get an intuition for how a list of numbers can represent a word’s context by considering the sentence: ‘And mares eat oats and does eat oats and little lambs eat ivy.’ If we count how often any two words occur next to each other in this sentence, we get the following counts for the words ‘does’, ‘lambs’, and ‘mares’.

Looking at these lists of numbers, you might notice that the local context of ‘does’ is identical to that of ‘mares’, and that they are both different from the local context of the word ‘lambs’.

People thought the traits of friendliness and helpfulness were very likely to occur together

This example might not seem especially interesting. But if we take a much longer input text containing many more different words (say, 50,000 unique words) and use much longer vectors, then we can draw more detailed conclusions about how similar the typical contexts of any two words are.

It turns out that similarity of context gives us a great deal of information about word meanings. For example, we immediately learn something about the sad fate of a little lamb in our world by noting that the five words with the most similar vectors to the word ‘lamb’ are ‘veal’, ‘tenderloin’, ‘meat’, ‘roasted’ and ‘roast’. Note, importantly, that words with similar vectors are not necessarily synonyms. The word ‘roasted’ does not mean the same thing as the word ‘lamb’, though their vector similarity tells us that the words tend to occur in similar contexts. So, we can mathematically measure how much two words ‘hang out’ together in linguistic space – and use that as a clue to how people might perceive the corresponding concepts in the real world.

In our studies, we asked people to estimate how likely it is for someone who has one trait (say, intelligence) to also have another trait (such as honesty). Then we checked if those judgments could be predicted based on the similarity of the vectors for each term. If the judgments were predictable in this way, it would support the idea that people are judging the co-occurrence of character traits based on common patterns of word usage.

We found evidence that this is happening. For example, people thought the traits of friendliness and helpfulness were very likely to occur together, and their word vectors were also similar. In contrast, the traits of agility and genuineness were judged to be unlikely to co-occur, and their word vectors were also dissimilar.

We wanted to ensure, however, that these judgements were not just based on whether the words had similar meanings. After all, a person who is courageous is also surely brave. So, we asked a different set of participants to judge how similar each pair of words was in terms of their meanings. As we had intended in selecting our word pairs, their meanings were rated as not very similar. For example, a person with the trait of kindheartedness was judged likely to also have the trait of consistency, but the meanings of these words were rated as very different. Similarly, approachability was judged to have a high likelihood of co-occurring with the trait of loyalty, despite different meanings. The key thing was that the words for these traits are used in similar contexts.

One potential criticism of our analysis is that linguistic context might only reflect the halo effect, not explain it. That is, if a person with one desirable trait is commonly assumed to have other desirable traits, then the words for these traits might end up being expressed in similar contexts as a result. However, context similarity in language is influenced by a broad range of factors, such as cultural norms and personal experiences, and these factors interact in complex and often unpredictable ways. It’s impossible to attribute the context similarity of words such as ‘consistent’ and ‘kindhearted’ to any single factor or mechanism. We argue that the ways trait words are used in language don’t merely reflect our mental associations but also help to create and reinforce those associations over time.

It is possible that some traits, such as intelligence and honesty, may be actually associated to a degree in some individuals. But research on personality psychology suggests that the correlation between traits such as intelligence and honesty is typically weak, and certainly not universally consistent. Thus, while some overlap may occur, it does not fully explain the erroneous associations involved in the halo effect.

Our brains soak up associations between concepts and spit them out as quick, automatic judgments

If these traits are not inherently linked in individuals, one possible explanation for their co-occurrence in language – and their association in people’s minds – is the influence of cultural narratives and societal norms. Many cultures tend to connect intellectual ability with moral virtue, reinforcing the stereotype that intelligent people are also honest, kind or trustworthy. These cultural beliefs are reflected in language, where the traits are often used together in discourse, further perpetuating the assumption that they are linked. Over time, these linguistic patterns become ingrained in the way people speak and think, influencing not only how we describe others but also how we unconsciously evaluate them – leading to the halo effect.

Our brains are language-hungry sponges, soaking up associations between concepts and later spitting them out as quick, automatic judgments about people. If you interview a job applicant who is courteous, for example, you might assume that they will also be helpful – an assumption that could turn out to be false. Your assumption may be underlain in part by the fact that the words ‘courteous’ and ‘helpful’ often appear in similar contexts in the language you’ve been consuming throughout your life.

Unpacking the halo effect using language patterns could have many practical applications. By quantifying the context similarity of two words, it may be possible to account for some of the variance in how individuals perceive and evaluate people, products, or ideas. For instance, in mental health, there have been growing concerns about incorrectly diagnosing people with two different conditions. This has been attributed in part to the halo effect: one diagnosis may influence the likelihood that another disorder is perceived. However, if we can spot which diagnostic labels are used in similar contexts, that might help clinicians guard against bias.

There could be another practical application related to marketing and advertising. Questions have been raised about the ethics of using language that misleads consumers into believing products are healthier than they truly are. For example, some research found that using the term ‘natural’ in advertising cigarettes led consumers to mistakenly believe that the cigarettes were healthier and had less potential to cause disease. A calculable measure that indicates how likely one word (such as ‘natural’) is to evoke others in the minds of consumers might help policymakers judge the acceptability of certain terms in marketing.

Then there are the judgments people make about each other in everyday life. Let this article serve as a reminder that the next time you find yourself thinking that someone has a delightful personality or a bright mind just because they have a dazzling smile, you might be under the spell of the halo effect. However, the more we understand how and why people mentally link certain traits together, the better we can guard against quick, unfounded judgments.