At the height of the thing, I’d gone half a decade without eating fruit. I passed by bins of berries and apples at the grocery store – piles of produce radiating with juicy, sugary danger, wild and immeasurable. I turned instead to the safety of my low-carb protein bars: rectangular and exact, comforting handholds on control. I fuelled the machinery of my body on polydextrose and erythritol, sweetness empty of energy; I tallied my life in grams of protein and net carbohydrates, little pencil-strokes in the margins of my books.

It was the logical conclusion of a process that had started years before, and in good faith. I’d been a new adult of 21, still living in my native Florida. It had been my boyfriend’s idea – a skinny nerd I’d met on an app before it was common to do so, holding my sharp wit out in front of my round body like a weapon. When I told him I’d been counting calories on and off since I was eight years old, he insisted I was doing something wrong. Over the cache of Mountain Dew cans crowding his gaming desk, he showed me the r/keto subreddit. Butter and steak on a diet? I was sceptical, but I had nothing to lose.

And then, I lost it.

The weight fell off like water. In a year, I was unrecognisable – and so was my life. I could walk into any shop and watch size-small clothes fall gracefully over my body in the dressing room mirror. Where I’d once been overlooked – or even jeered at – I now received smiles from strangers. Men were suddenly approaching me, asking for my time – which I offered. In thrall to the turning heads I’d begun collecting, like the achievement points in my boyfriend’s video games, I unilaterally made the call to open our relationship.

You can leave if you want, I told him, but I’m going to sleep with other people. At the time, it was easy for me to dismiss this cruelty of mine: he’d given me the key, after all, to this novel influx of attention.

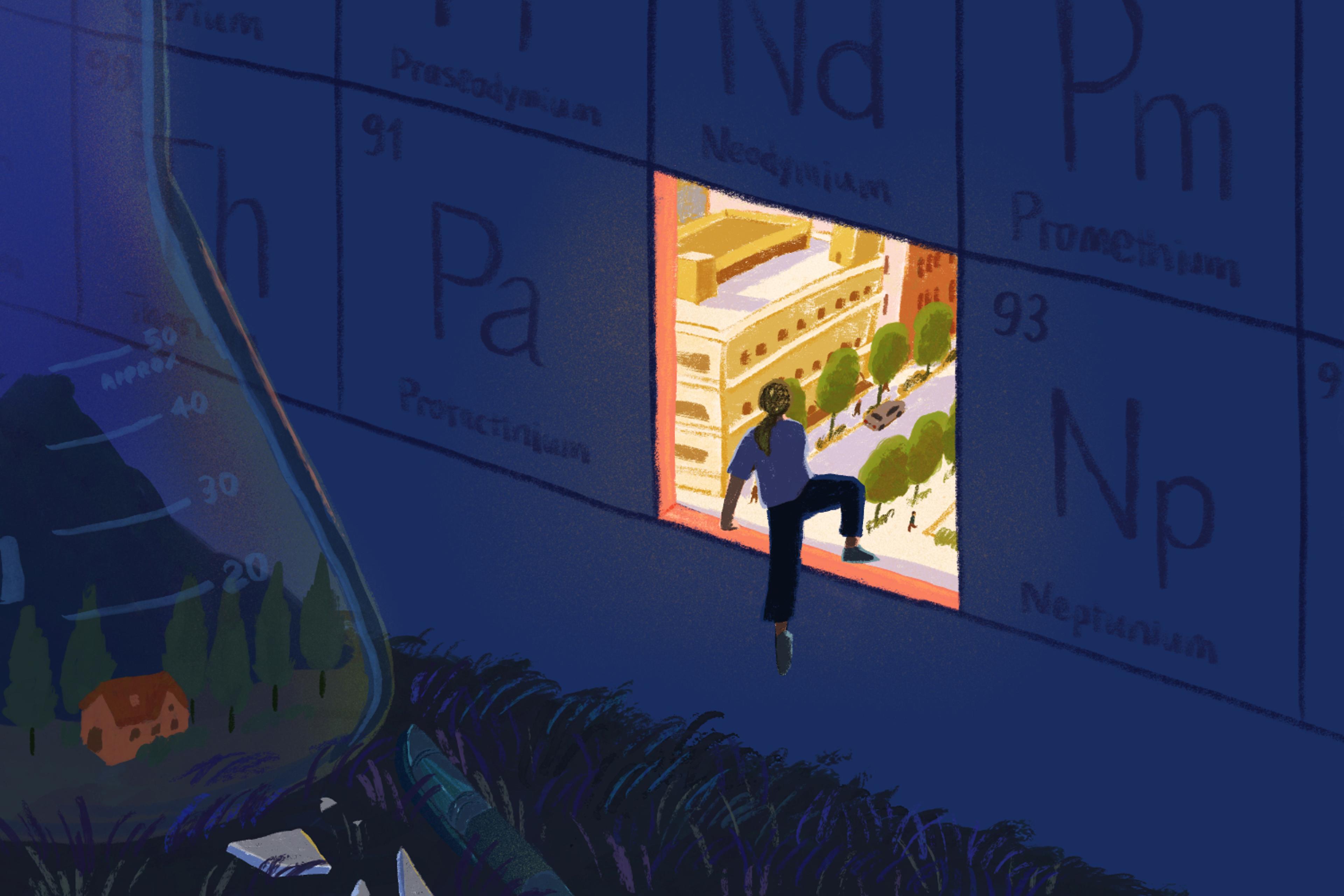

I had always imagined beauty as a locked door. Once I narrowed my body to the proper dimensions, it would swing open, offer me ingress into the bright room beyond. In many ways, I was proven right. Doors were, literally, held open; places in line offered up. The world unfurls itself at the feet of beautiful women, I wrote one night in my journal, after the beautiful man who’d been waiting my table invited me to a beachside birthday party, propping me on the back of his motorcycle to get there.

Maintaining this new life was a matter of survival. I had to keep the door open at any cost.

Growing up fat, I’d always fantasised about being elsewhere – and not just to escape the swampy air and bikini-tops-and-cutoffs culture of South Florida. Being the fat girl at school marked me with an unwanted and un-wash-offable identity. My body was a sandwich board that told those around me everything they needed to know before I could open my mouth.

In being elsewhere, I thought, I would be automatically elsewise: a new self in a new place with a new body – or at least a new chance to better position and inhabit this one. As a child, I soothed myself on the promise that things would get better: once I got to middle school, once I got to high school, once I got to college. But everywhere I went, I brought the albatross of my body. There was no reinvention – until there was.

By the time my relationship fell apart entirely, I was working as a freelancer – which meant I could be anywhere. My window to elsewise had finally arrived. I put remaking myself into high gear: tucking the newly legible words remote nomad into my Twitter bio, I set off alone, arriving at each new place a new woman – one who had never been anything but beautiful.

I dismissed his comment as misogyny to make myself impermeable

It was a privilege to see so much of the world. I drove across the US seven times, taking dirt-smeared selfies at national parks from the Badlands to Glacier to Saguaro. I took a one-way flight to Europe and lived for a month in Spain, another in Athens. But, in the meantime, my dieting devolved into full-blown disorder: my period stuttered, then disappeared. I survived on my chalky bars and iceberg lettuce, on undressed plastic-package salads eaten surreptitiously in my car in grocery-store parking lots. I worked out two hours a day, every day, even with shin splints or strep throat. Sweat-salt collected on my gym clothes, a white crust I took pride in as I fed my stiffened wardrobe into laundromat machines.

At a nail salon in Louisville, Kentucky – making myself ready between more exciting stops at the coasts – the man doing my pedicure asked after my story. I told him a little: solo adventuring around the world; putting experience first; trying to see everything.

He chuckled and shook his head.

What? I asked, a little annoyed.

No friends? No boyfriend? He responded. Boring.

I leaned back in the chair, rolled my eyes, stopped talking. I dismissed his comment as misogyny to make myself impermeable. My ire, I see now, made plain the truth in his words. I never for a second would have admitted I was looking for somewhere – someone with whom – to stay.

Malnutrition harms the body in myriad ways. In the absence of nutrition, muscle is cannibalised for energy. The immune system grows sluggish. The heart can shrink and slow.

But the true mechanism of dysfunction in an eating disorder is isolation. The word companion literally means ‘bread friend’.

To avoid eating is, necessarily, to avoid human relating.

I’d narrowed myself into a perfectly curated depiction of a woman who lived nowhere – my constant self-vigilance at odds with the unfettered experience I said was my aim. I floated above the earth rather than on it. So with my relationships, too. Again and again, I presented a hollowed-out version of myself to men who would never have otherwise looked. When the sex was over, I asked them to leave. Anorexia demanded loyalty, wanted to get me alone.

When I gained three pounds, I imagined people would instantly recognise the truth of me: that I was a failure

Only years later could I see that I had gotten it all wrong, reaching toward love in exactly the ways in which I was sure not to find it. The truest form of love I could have had – the friendships I had already – I denigrated and distanced myself from. When childhood friends sent a check-in text or commented on an Instagram photo, I largely ignored them. Those people had known a version of me I was trying to bury. Their love threatened to revive her.

By this time, I’d landed in Santa Fe – a city I stayed in for a whole year and was desperate to call home forever. But the well was poisoned from the start. I was dogged by the tension of trying to be that new, beautiful woman on a full-time basis. When I slipped and gained three pounds, I imagined the people around me – the people I saw every day – would instantly recognise the truth of me: that I was a failure.

Then came the high-desert winter with its rind of flaking frost, its bitter gusts, nights dipping to single Fahrenheit digits. I found myself waking up and ambulating to the kitchen as if in a fugue state, spooning nut butter helplessly into my mouth. I tromped out in the snow to my car, where I’d stashed my protein bars to disincentivise myself from eating them. I devoured them with animal hunger, four at a time.

Three pounds became five, became 15 – the illusion of me falling apart.

The pendulum had started to swing without my consent or intention. In just six months, I gained back half the weight I’d lost eight years before, and remained there. My body had won: more than I wanted to be thin, it wanted to live. For the first time in a decade, I was eating whatever I wanted: granola swimming in whole milk, a bag of pretzels, the heel of a fresh baguette ripped toothwise from the loaf.

Still, to allow it, I displaced myself once more. I couldn’t stomach the idea of my desert acquaintances seeing it happen in real time: my softening, my reveal. In Portland, I had an older friend – one who had known me as a frightened, fat 14-year-old. I was finally ready to turn away from reinvention, back toward the stable story of self.

I return to stain my hands purple. I lose the tempo of time. I feel utterly found

That summer, she took me berry-picking – a joyful July tradition she’d partaken in with her partner since they’d moved to Portland years before. We laughed on the drive out to Sauvie Island, watching the urban Portland landscape fading into quiet agrarian stripes. She taught me how to find the densest clusters of the sweetest fruit: to walk further down into the rows where fewer people go, to reach my hand back into the foliage. She ate as she went, holding half the harvest in the box she carried and half in her belly. I followed her lead, each fruit sparkling with the sweetness I’d so long foregone.

I let her be again – after a long lapse – my companion.

It has become a tradition, part of what it means to be at home, here. Each summer – five, so far, and soon six – I return to stain my hands purple, to pull blue- and black- and marionberries, one by one, from their vines. I do it again and again until the half-flat in my other arm is overflowing. I lose the tempo of time. I feel utterly found.

I bring my old friend – or one of the new ones I’ve made. Real friends, the kind who’ve seen me weep, seen me eat. I’ve brought lovers, ones I’ve actually slept with after sleeping with them. I do go alone sometimes, but the timbre of it is different. I am not self-isolating, but enjoying a moment of solitude. When I get back to town, I share the bounty with my neighbours. The fruit goes fast, but all the better: a reason to go back again.

And I feed myself – even as I’m picking. It is an immediate kind of nourishment to pluck fruit from where it grows, to remember this larger order from which I was never, in fact, separate. As I press each sun-warmed berry – and the dirt that survives a precursory brushing-off – into my mouth, I am tying myself to this place, to my body. I pull it into myself, this fleeting light that’s been alchemised into sweetness.