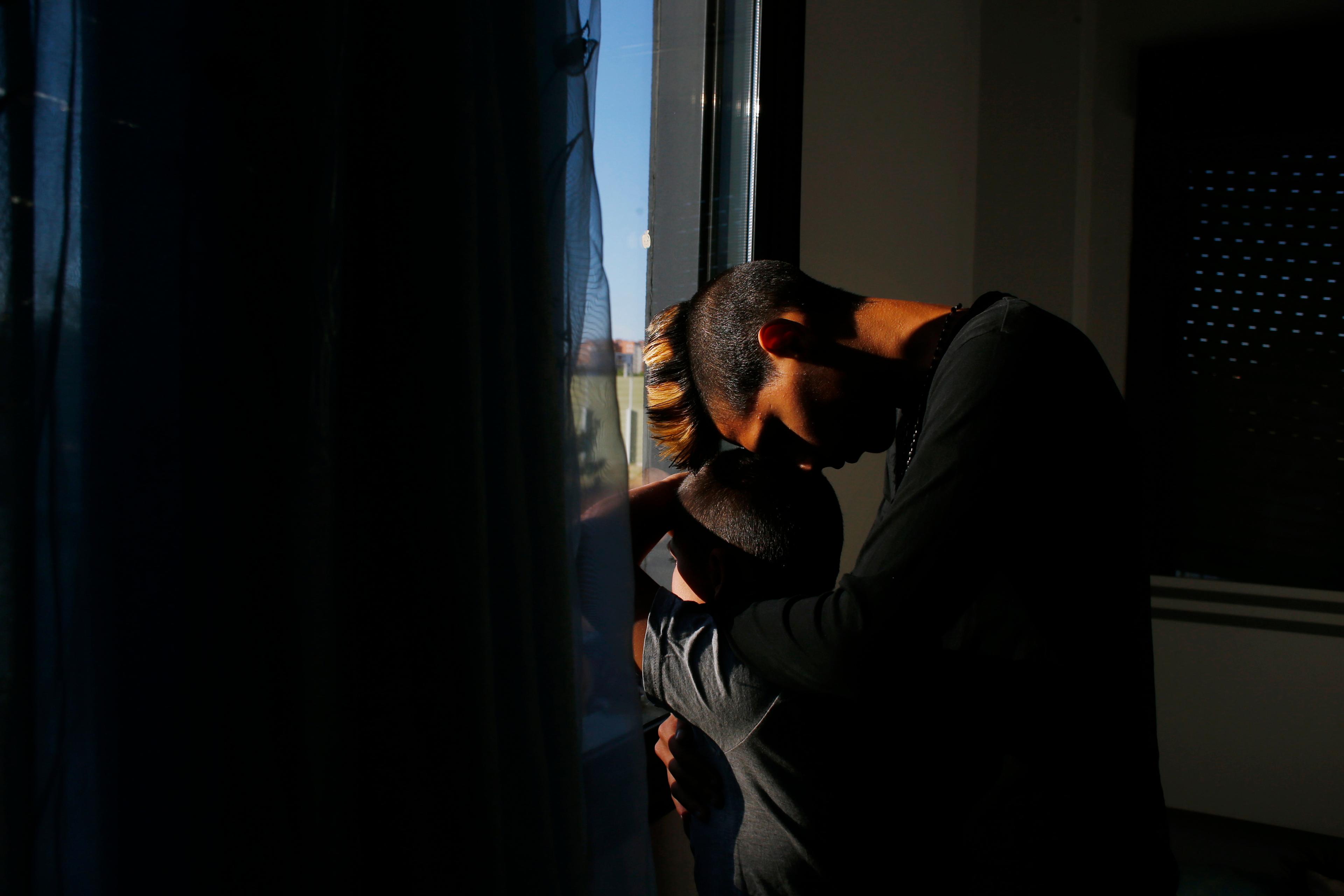

When an important person in my life was arrested for online offences it was [as] if a bomb went off in my life (followed by countless grenades). At the same time, I was immediately and automatically transported to another place … I quickly discovered that [this] is primarily a place of grieving. Alongside this grief are immense loss, fear, shock, confusion, betrayal, and seething anger … A black tattoo appeared across my forehead. It says: ‘The man I chose to father my children is a convicted sex offender.’

– from a public, online family support forum

Sexual offences impact the lives of many people. While attention understandably goes primarily to the victim/survivor, there are others who are also profoundly affected and often overlooked. Among these are the family members who come to realise that their loved one has harmed someone sexually. This may be especially difficult when the harm is against a child. The families of individuals in sex-offender registries often experience shame, social isolation and property damage, and may even be forced to move house.

People often expect that these family members will respond to the situation with immediate revulsion and rejection, and sever ties with the wrongdoer in their midst. Perhaps you have this expectation as well. However, for family members who have undergone this harrowing experience, it is far from a straightforward process.

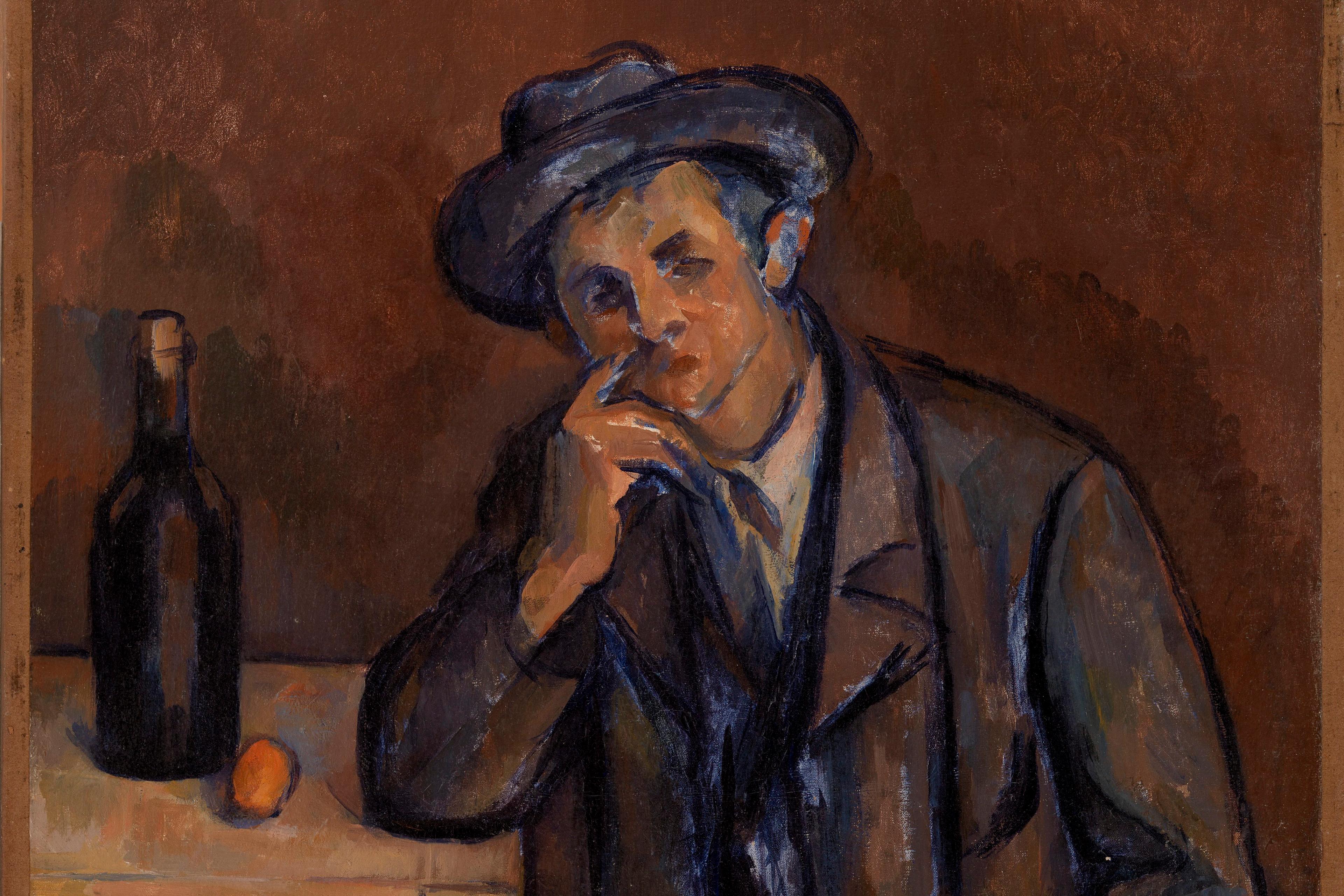

To outsiders, an individual who has committed a sexual offence becomes defined solely by that reprehensible act: they are nothing but a ‘sex offender’. Other aspects of the perpetrator’s character are overshadowed by the worst action they have taken. These evaluations make the person easily disposable to those who do not know them. But, from the perspective of the people closest to them, the individual in question may have been a loving parent, a caring child or a devoted spouse. They see the perpetrator with all of their humanity: a mixture of positive and negative traits.

The experience endured by family members can lead to a complicated form of grief. Suddenly, they are confronted with a version of their loved one that they no longer recognise. The disparity between the image they held of their cherished family member (someone trustworthy and caring) and the harsh reality (someone who has inflicted harm) is often shocking. The incident can be extremely difficult to process. In the case of a wife whose husband has committed child sexual abuse, for example, she not only grapples with the shame and stigma associated with his crime but also with a sense of betrayal and loss. Even though her husband is still alive, she might feel that she has lost the man she knew and loved.

Disenfranchised grief is a term used for certain types of grief that society does not recognise and validate. Some forms of mourning not only don’t attract sympathy from others but may also bring disapproval, humiliation or blame upon those who bear the burden of loss. Another example of disenfranchised grief occurs when someone mourns the loss of a pet for a longer duration than society expects. The significance of losing an animal compared with losing a human loved one is often underestimated, resulting in the trivialisation of the mourner’s grief.

The family members of people who have caused sexual harm are wounded and ashamed because of the crime committed by their loved ones. But because they often retain, in their minds, the humane part of their loved ones – who, for many others, embody evil – people outside the family may refuse to sympathise, and direct blame and hatred toward them as well.

A family member may remain silent because they, too, have been victimised by the perpetrator

The family members may face questions such as: ‘How can you continue to live with him?’ ‘Why don’t you disown your son?’ ‘How can you possibly still love that person?’ These questions put pressure on family members to maintain a distance from their loved one. They may start to blame themselves because of their inability to meet such expectations, or because they placed trust in the perpetrator, or for not having recognised the abuse.

In many instances, family members had no awareness of what was happening; this is often the case when child sexual abuse occurs online. Nevertheless, even in these situations, they might unjustly be seen as complicit. In some cases – in particular, when child sexual abuse occurs within the family – one or more family members other than the perpetrator might have known about the abuse, or become suspicious, yet remained silent or passive. There are various reasons why people remain bystanders of sexual abuse: denial, fear of dishonour and consequent social judgment, unwavering support and belief in the perpetrator, disbelief or blame directed at the victim. Sometimes, a family member may remain silent because they, too, have been victimised by the perpetrator. In such cases, breaking the silence requires them to confront their own unspoken trauma. Some might be trapped in a cycle of abuse and fear that speaking up could make the situation worse. These individuals might wrestle with self-doubt resulting from years of being gaslighted. Each case is unique, and the presumption that all family members are complicit is an oversimplified generalisation.

Unfortunately, a lack of public understanding about the complicated nature of sex crimes may lead people to blame parents for nurturing a ‘sex offender’, or blame a partner (usually the female partner of a male perpetrator) for failing to satiate the perpetrator’s sexual needs, which some people perceive as a primary reason for the crime.

While some psychological problems can be linked in direct and indirect ways to the nuclear family and the childhood environment, the factors involved are intricate and, often, risks arise from the complex interplay of numerous biological, developmental and social factors. Although it is true that some individuals who sexually harm may come from dysfunctional families characterised by violence, poor sexual boundaries, addiction and maltreatment, others have not experienced significant familial dysfunction. Therefore, just as it is incorrect to assume that the negligence of parents or caregivers is always responsible for a child’s sexual victimisation, family members of perpetrators cannot automatically be presumed worthy of blame.

What about those who continue supporting someone who has committed a sexual crime, even after the offence has been exposed? Does offering support mean enabling the perpetrator to pose further harm? Is it impossible to disapprove of someone’s act while still accepting them as a human being and supporting their rehabilitation?

In most well-known rehabilitation programmes for people who have committed sex offences (eg, the Good Lives Model), improving personal relationships is an integral part of the treatment plan, along with cognitive, emotional and behavioural issues, education and employment. Family can contribute to the development of strong moral foundations and social bonds. It is also an informal source of social control and supervision. Healthy communication with family members plays a crucial role in a person’s sense of belonging and responsibility towards others, which discourages criminal conduct. A supportive family environment can actually serve as a protective factor, helping to reduce the risk of re-offending. Conversely, family rejection and social exclusion have been well documented as risk factors for all sorts of crimes, including sexual crimes. Hence, pressuring the family to cut ties does not seem to benefit anyone.

If you know a family in this situation, there are things you can do to provide support. It’s valuable to maintain a sense of connection with them rather than cutting off relationships or avoiding them. Do not assume that every family member is complicit in the individual’s offence. Think about the unfortunate circumstances they have faced – the possible shock, anger, grief and shame. Interact with them as you normally would. If you are part of the immediate family’s circle of relatives or close friends, you can offer simple greetings or reach out with a brief, non-intrusive phone call. Consider asking open-ended questions like ‘Is there anything I can do for you?’ and offer whatever assistance you can give. This shows your willingness to support them and allows them to express their needs or concerns if they wish to do so.

Children in a perpetrator’s family are particularly vulnerable to emotional harm. Their everyday lives might be disrupted, with a loved one (eg, a parent or sibling) leaving the household or being arrested for reasons they may not fully comprehend. They might also witness other family members’ anger and despair. Understanding and processing these incidents can be immensely challenging, especially for younger children. Age-appropriate information about the incident should be shared only by a parent, a trusted adult close to the child, or a mental health professional.

If you have children, it is advisable not to involve them in what has happened. Efforts like keeping your child away from the perpetrator’s child at school or telling your child that ‘Tom’s father is a criminal’, ‘a bad person’ or ‘a paedophile’ are not relevant to your child’s safety. Let children be children. Such reactions may unnecessarily make your child feel anxious and insecure, or make the perpetrator’s child a target of bullying at school when word gets spread. Instead, explore the best ways of providing age-appropriate information that helps your child recognise and navigate potentially unsafe situations (eg, teach them to avoid accepting rides from strangers, including parents of their classmates).

Sexual offending inflicts harm and triggers intense emotions. The temptation to yield to anger, hatred and judgment, and not just toward the perpetrator, can be strong. But by refraining from judgment and considering the wellbeing of affected family members – especially the ones who are most vulnerable – the people around them can take proactive steps to mitigate the extent of the harm.