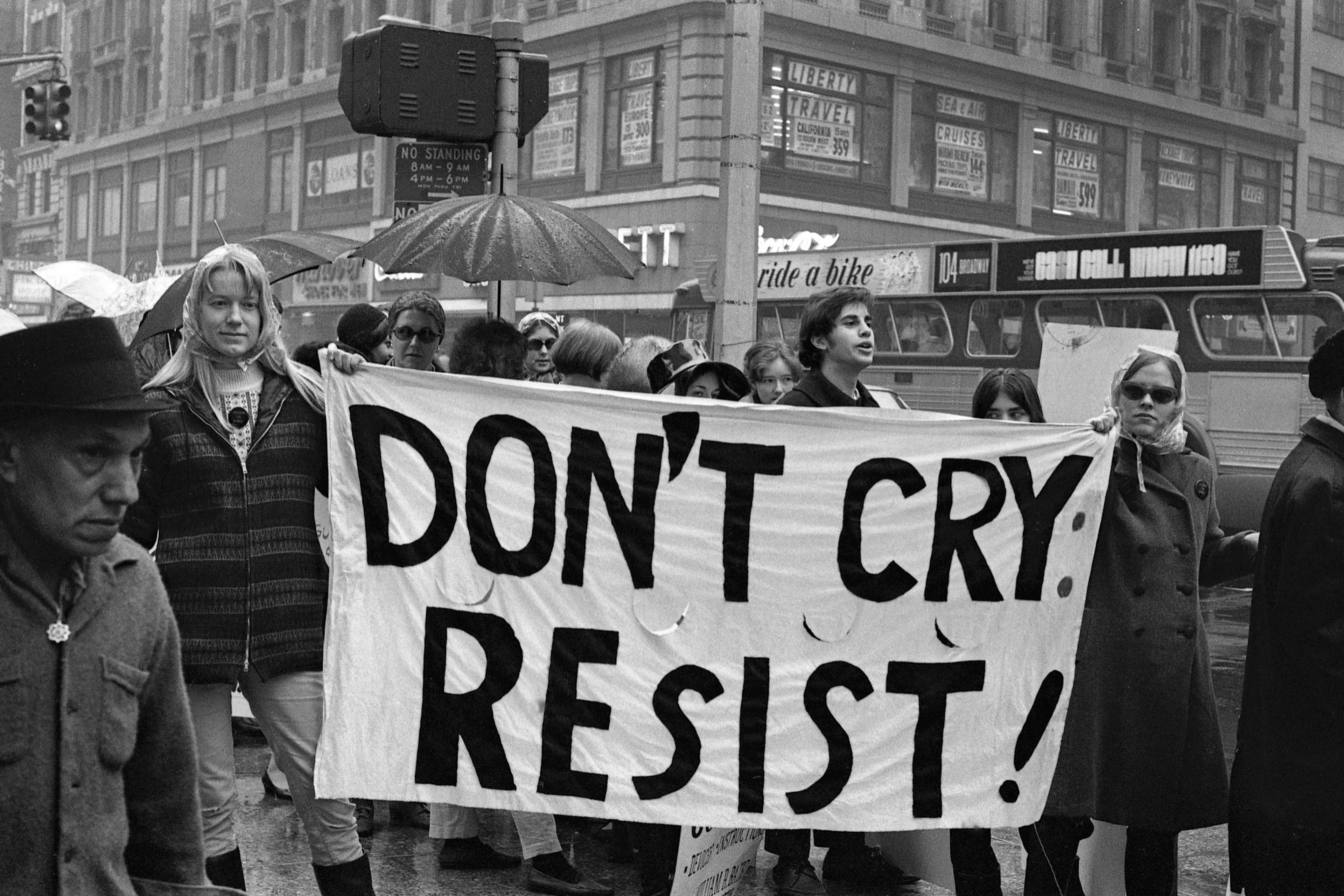

To better understand what it’s like to deal with democratic heartbreak, we would do well to pay more attention to artists such as Langston Hughes (1901-67), a committed political radical. Hughes’s poetry speaks to anyone ‘vitally concerned’ about their country’s ‘mores, its democracy, and its well-being’. He gives us an inspiring account of what a political community could look like and what a citizen might do in the face of injustice and neglect. Hughes’s advice is twofold: first, to see the community as it is, forged through material contest. Second, Hughes shows how to practise the ethics of melancholy citizenship. In doing so, he offers a style of democratic politics that taps into people’s pain to lift them to opportunity and more meaningful forms of belonging.

Hughes calls the people ‘humble, hungry, mean … despite the dream’. Whether one is ‘the poor white, fooled and pushed apart’ or ‘the Negro bearing slavery’s scars’, ‘the red man driven from the land’ or ‘the immigrant clutching the hope I seek’, all must live in the space between abstract ideals and the bitter world. To create a world better than the one into which we are born, Hughes urges victims of colonisation and slavery to find ways to discover common ground with beneficiaries of past injustices.

In his posthumously published poem ‘Dream of Freedom’ (1994), Hughes describes the longing for universal freedom as something that ‘knows no frontier or tongue, … no class or race’. He urges listeners to not fall into the trap of insisting that liberty could be ‘kept secure / In any one locked place’. No single group’s suffering should be reified or become an insurmountable obstacle to progress. Building a just society requires toggling between particularistic pain and humanistic triumphs, just as it calls for local fights to become integrated into larger struggles.

Hughes understood that citizens are transformed and reborn through shared struggle. His poetry articulates four democratic virtues associated with a mournful style of politics: candour, pensiveness, fortitude, and self-abnegation. Together, these traits illuminate how to sustain political faith while dealing with disappointment, living in a world filled with injustice.

The first attribute is the capacity to honestly appraise democracy’s deficits. Hughes writes about the importance of seeing society ‘with clear, unprejudiced eyes’. It is no accident that the concept of justice is often represented by a blind goddess. In pointing this out, his purpose is not to recycle the platitude that justice is impartial, but instead to suggest that the ‘bandage hides two festering sores / That once perhaps were eyes’.

For Hughes, realising that legal justice suffers from disfigured eyes allows us to confront unpleasant truths. In ‘Poem to a Dead Soldier’ (1925), he highlights the ‘soft lies’ uttered by patriots to send innocent young people off to war. After their deaths, ‘we make soft speeches / And sob soft cries’.

The point of his emphasis on candour isn’t to recommend that victims of injustice wallow in misery. Rather, it is to show that the citizen’s central dilemma is holding two ideas at once: we must become better than we are alone, and it is also disappointing that we have yet fallen short of doing so. How to re-engage each other in ways that can make coalitions must be the central task of democratic politics. Without giving this crisis of faith its due, and discovering means of forging solidarity, justice remains unattainable.

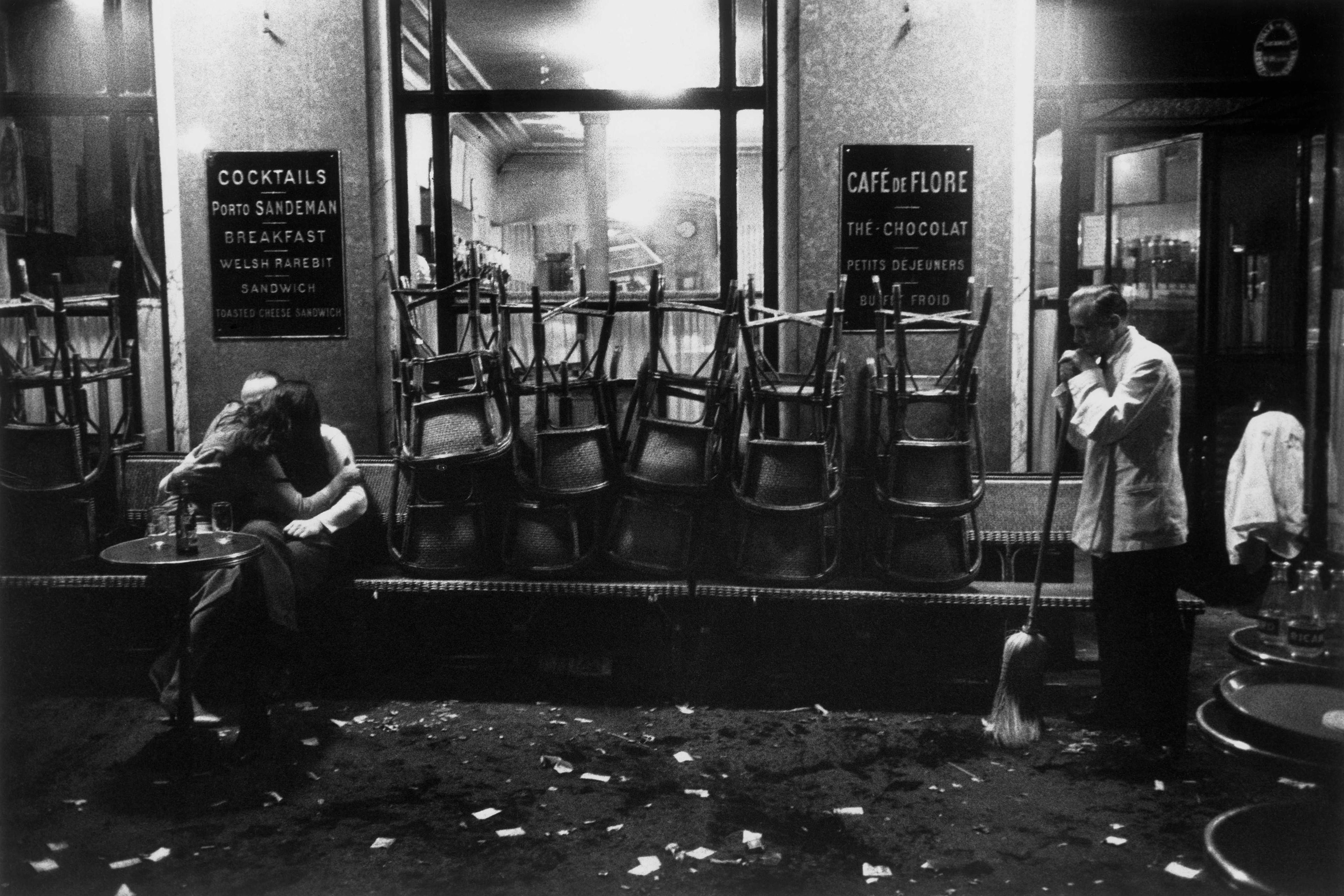

Importantly, confronting social misery can increase the risk of demoralisation. Noticing what was previously easy to ignore – the evidence of inequality, degradation and hypocrisy – could deepen the crisis of democratic faith. Most do not do well with this discomfort, once we give up telling each other soft lies. The temptation is great to retreat to an overly tidy revision of the past to assuage our disquiet or nurse our wounds with abstract promises. Hughes suggests an alternative disposition: that a pensive approach may open us to the gap between perfection and damnation. As the poem ‘Call to Creation’ (1931) instructs: ‘Give up beauty for a moment.’ Instead: ‘Look at harshness, look at pain / Look at life again.’ Dispensing with fantasies, at least for the moment, allows us to recognise the humanity of all who suffer.

For Hughes, a constructive politics can’t devolve into merely lashing out; it cannot consist of haranguing and ostracising those who don’t fall in line. It must move beyond the alienating politics of recognition for recognition’s sake. Instead, it must be focused on promoting broad appreciation for the entirety of ‘life again’.

A melancholy disposition offers an alternative to the belligerent, often empty, patriotic stance demanded by nationalists and traditionalists. It avoids the haughty posture of intellectuals who have given up on the possibility of peace and justice, and are content with managing appearances over expanding material opportunity. Hughes never wants anyone to forget that falling short of ideals is not proof that ideals should be abandoned. For, after noticing ‘there are stains / On the beauty of my democracy’, one ‘want[s] to be clean’.

Hughes insists that a blues-like state is the antidote to watching elites overpromise and underdeliver. ‘I got the Weary Blues’, Hughes intones, ‘And I can’t be satisfied.’ To reach across experiences, he implies, one need muster ‘a deep song voice with a melancholy tone’.

Hughes alludes to fortitude as the third facet of melancholy citizenship when he says, in ‘Let America Be America Again’ (1936): ‘Sure, call me any ugly name you choose – / The steel of freedom does not stain.’

Fortitude is critical to progress because, as Hughes put it in the poem ‘Freedom’ (1968): ‘Some folks think / By killing a man / They kill / Freedom.’ To the contrary, Hughes insists, ‘Freedom / Stands up and laughs / In their faces’. Steeling oneself against the debilitating effects of self-doubt, ridicule and threats makes it possible to muster the will to remake the world: ‘To smash the old dead dogmas of the past – / To kill the lies of colour / That keep the rich enthroned’ (from ‘A Letter to the South’, 1931).

Dark humour runs through several poems. As Hughes explains in ‘I, Too’ (1926):

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

The table metaphor shows there is a place for all to be nourished, and reinforces the importance of welcoming strangers.

The fourth virtue of melancholy politics is subordinating the self to a greater cause. If a just society is the goal, then solidarity must be forged through service to others. Humility, putting oneself in another’s shoes, a willingness to forgive must all be part of the democratic relationships. ‘Alone, I know, no one is free.’ In ‘Alabama Earth’ (1932), he proclaims: ‘Serve – and hate will die unborn. / Love – and chains are broken.’

These are valuable lessons today, as it has become popular among many to cut ties with family members, friends and colleagues over political disagreements. Politics relying on relentless disaffiliation and ostracism are incompatible with the ethics of charity and community-building, and ultimately corrode democratic ties.

Hughes suggests that labels are meant to be subverted, not turned into orthodoxy. In ‘Good Morning Revolution’ (1932), Hughes personifies political transformation as someone those in power have labelled ‘a trouble maker, a alien-enemy’, but is actually ‘the very best friend / I ever had.’ After, he says:

But me, I ain’t never had enough to eat

…

Me, I ain’t never known security –

…

Together,

We can take everything

…

And turn ’em over to the people who work

Rule and run ’em for us people who work.

Hughes is interested in how others label him, but is neither obsessed with how to label others nor does he insist on particular names or titles for himself. Indeed, oppressors themselves are often preoccupied with labelling, sorting and controlling. The lesson for us is obvious: whether antiracist or racist, democratic socialist or capitalist, anyone can join ‘the people who work’. Demanding ideological purity can undermine the coalitions that are necessary to help everyone get ‘enough to eat’ and some economic security.

In another posthumously published poem, ‘In Explanation of Our Times’ (1994), Hughes playfully runs together the insulting names oppressors use to denigrate the oppressed in order to create a form of rhetorical solidarity. The combination is jangly and nonsensical, yet models the impulse to create something fresh: ‘George Sallie Coolie Boy gets tired sometimes.’ His aim isn’t to police individual labels or names or affiliations, but to leverage others’ perceptions of outsiders to create solidarity and power. Only then can practitioners of melancholy politics knit together people from different nations in a mighty wave of revolutionary action:

So all over the world today

folks with not even Mister in front of their names

are raring up and talking back

to those called Mister.

From Harlem past Hong Kong talking back.

Poetry can reach people where they are, using the grammar of the streets rather than the alienating terminology of academics or ideologues. It can repair and rejuvenate, provoke and motivate.

Of course, a melancholy style alone cannot fulfil the ends of justice. It doesn’t necessarily help us make hard choices between short-term gains and long-term advances. Despite these limitations, melancholy citizenship is a potent supplement to our democratic soul and a safeguard against counterproductive politics.