Imagine you are planning to learn about the solar system but, before you start, your teacher gives you a multiple-choice quiz on the topic. You haven’t learned a single fact about the solar system yet, so the questions, such as ‘Which of our dwarf planets is not a plutoid?’ or ‘Which planet is the least dense in the solar system?’, leave you staring blankly. Naturally, you are bound to make mistakes. You might understandably feel that this guessing in the dark is a complete waste of time. In fact, it’s not – a growing body of research shows this early test can significantly enhance your later learning.

The potential of tests, not just for assessment, but also for learning, dates back at least as far as the 1920s when the psychologist Sidney Pressey developed his innovative typewriter-turned-testing machine. The machine presented a question with several possible answers, requiring students to press a key to submit their response. Pressey’s innovation was a feature that held the question in place until the correct answer was chosen, transforming the test into a learning experience. Although it wasn’t widely adopted, his work anticipated what is now known about the huge benefits of testing for improving learning.

The virtues of testing for improving recall and deepening learning have been widely researched, but the vast majority of studies have focused on the benefit of tests taken after studying. Research from the 1960s was among the earliest to highlight the benefits of testing before learning – what is now called the ‘pretesting effect’ – and in recent years there has been a surge of interest in this counterintuitive effect.

Here’s what experiments into the pretesting effect typically look like. All participants eventually study the same new information, but half are asked to answer anywhere from one to several dozen questions about the material before they have had a chance to study it – usually without feedback on their largely incorrect guesses. After all of the participants have studied the material, everyone then takes a final test to assess how well they’ve learned. Even though that pretest might seem pointless (why spend valuable learning time making wrong guesses?), over and over again, experiments suggest that it is time well spent. The pretest group typically outperforms the control group. Even incorrect guessing followed by studying benefits learning.

Pretesting acts as a metacognitive ‘reality check’, highlighting what you do and do not know

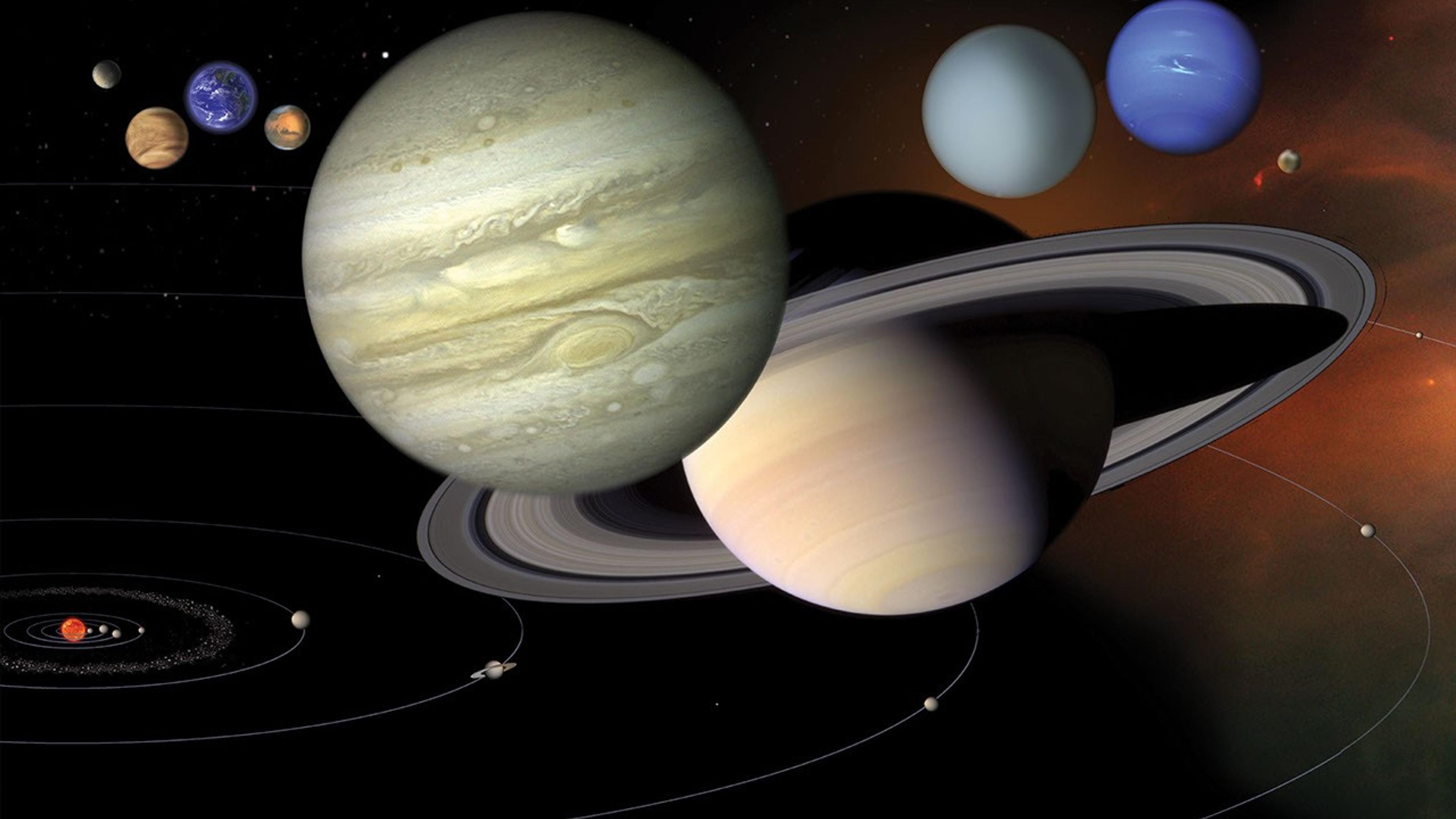

These benefits apply to simple materials, such as word pairs, and more complex ones, such as reading passages about physics or oceanography, watching videos on history or information theory, or attending live research-methods lectures. And this holds true for children learning about space exploration and undergraduates studying psychology; in the laboratory and in the classroom; and whether answers are scribbled with a pen on paper or guessed on one’s laptop.

Researchers believe pretesting is beneficial because it improves the way that we process the to-be-learned material. ‘We could talk for hours about the mechanism,’ says Steven Pan, a cognitive scientist at the National University of Singapore, who recently co-authored a review of the pretesting effect. ‘Making a guess might trigger things. Make you more curious.’

Increased attention to the to-be-learned material could be another factor. Pan and his colleagues have observed reduced mind-wandering after pretesting, and other researchers have shown that participants’ eyes focus more on sentences related to the questions they received in advance. Other potential mechanisms include an improved motivation to learn and that pretesting acts as a metacognitive ‘reality check’, highlighting what you do and do not know and encouraging you to fill in knowledge gaps.

Whatever the mechanism is, when you later need that information, you’re more likely to recall it after a pretest than if you had simply read it. As Pan explains: ‘If you have only read [the learning material], your chance of recalling that information is not zero, but it’s typically going to be less than if you had to make a guess first.’

Studies show that the benefits of pretesting can persist from one day to one week to several weeks, indicating that the advantages of a pretest extend well beyond the initial minutes following studying and that true learning is taking place. What’s more, newer research suggests that the effect may actually grow stronger over time, meaning its potency could have been underestimated in the many studies that only measured learning shortly after the study session.

If you want to try pretesting for yourself, keep in mind that it works best when the questions are focused on information that will be covered in what you’re about to learn. Though access to correct answers isn’t necessary for pretesting, feedback can still shape your learning experience and might be especially helpful when engaging with more complex learning materials. Faria Sana, a cognitive scientist at Athabasca University, explains that, in these cases, ‘feedback can scaffold learning and ensure that learners don’t reinforce errors.’

Also, note that the benefits of pretesting can diminish when there is a delay between the test and the learning session. So make sure you take the pre-quiz shortly before engaging with the learning material. For example, if you’re about to watch a video, take a moment to answer a few pretest questions right before hitting that play button. For longer or more complex materials – such as an entire book chapter or a lengthier video – try guessing the answers to a few questions before each chapter section or video segment. This way, your guesses will be made shortly before you encounter the answers.

As for where to source your questions, you could consider using the questions that are often found at the end of textbook chapters or provided at the end of a lecture (be that online, or at a learning institution). Another approach, if you’re studying from a book, is to ‘glance through and try to guess from the headings what information will be there. And then read and discover what’s actually in there,’ recommends Pan. Alternatively, Sana suggests that you can ‘turn learning objectives into questions and attempt to answer them before exploring the content’ or you could generate your own questions based on what you expect to learn. Pan adds: ‘You can even ask an artificial intelligence agent to help generate practice questions for you, then engage in pretesting with those questions.’

We often fail to recognise just how helpful pretesting can be, even after experiencing its benefits firsthand

The types of questions you choose can also influence the benefits you reap. Pretesting has been shown to work with a variety of question types, including multiple-choice, short-answer and fill-in-the-blank questions. However, when learning similar and therefore easily confused material, such as distinguishing between the eight wrist bones or the various moons of Saturn, question type can make a difference. A 2016 study found that including incorrect but closely related answer options in a multiple-choice test format can help direct your attention more broadly – both to the information necessary to answer the specific pretest questions and to the information related to the incorrect alternatives. Then, when you begin studying the learning material, this brief exposure to related information will help you notice and remember it better.

For example, before reading a study text about Saturn, you might first answer a multiple-choice pretest that included a question about its moons (‘What is Saturn’s largest moon? a. Titan, b. Rhea, c. Mimas; answer: Titan). This would prompt you to pay more attention to information about the largest moon (ie, Titan) and also to information about the other moons. ‘Then, if you were asked about the second-largest moon later, you would be better equipped to answer “Rhea”,’ explains Jeri Little, a cognitive scientist at California State University, East Bay and co-author of the study. In contrast, it would be less effective to take a pretest that required only short-answer questions. This would focus your attention solely on the specific question and its answer, making those questions less effective for promoting the learning of related material. For example, if your pretest included the question ‘What is Saturn’s largest moon?’ in a short-answer format, the pretesting effect would be limited to the correct answer (ie, Titan) without broadening your attention to think about Mimas or Rhea.

Scientists see pretesting as particularly useful for learning concrete concepts or facts, such as ‘Titan is Saturn’s largest moon.’ Although research has shown that pretesting can extend to procedural knowledge – such as the recent study in which individuals who attempted a medical procedure before watching a training video subsequently performed the procedure more quickly and with fewer errors than those who only watched the video – this area of research is in its early stages. Another guessing-based strategy that has proven effective, often in group learning, is known as ‘productive failure’. In subjects like mathematics, it involves encouraging learners to attempt solving problems before receiving formal instruction – and again there’s evidence that this form of guessing can result in better outcomes than instruction alone.

Pretesting, a strategy with almost no downsides, is unlikely to detract from any traditional post-learning tests you take and will likely improve your overall learning process. Given all the evidence for pretesting, you might wonder why it isn’t more commonly used. The truth is, we often fail to recognise just how helpful pretesting can be, even after experiencing its benefits firsthand. That’s why Pan calls it a ‘secret strategy’. In his teaching, he likes to open with a thoughtful question to ‘spark thinking about the lesson that is to follow’. With growing evidence in its favour, why not join Pan and others and give this secret strategy a try?