Eighteen years ago, I was deep in the throes of addiction to booze and benzos. At the end, every morning was the same. I’d wake up only to be greeted by the excruciating recognition that I had failed yet again in my resolution to stop using. The feeling was much more existentially profound and penetrative than the guilt I also felt for drinking oceans of vodka in the previous decade. My problem was qualitative. It was about who I was as a person, about the quality of my character. I was ashamed of myself, ashamed of being me. There was a remedy that I enacted like an automaton. I’d drive to the nearby BP station and buy several morning beers that would ease my physical distress and dull the psychic shame until the next day when the exact same script would repeat.

I was an addict in a self-sustaining double bind: I used, eventually and in part, in order to mitigate the shame of addiction. It worked. But using each day in order to dull or defeat the shame of addiction seeded further shame the next day, and thus provided a powerful reason to drink and pop pills on each new bleak morning. Huis clos, no exit.

Many compassionate people, including many clinicians, think shame can serve no useful role in recovery from addiction. There are two arguments. First, that shame is uniquely toxic because, like the shame I just described, it is often global, a negative emotional evaluation of who one is: I am a failure as a person. It makes little sense to think that such an evaluation could seed or motivate a healthy confidence that one can overcome the addiction. It makes much more sense to think that experiencing the shame of addiction provides a new reason to use. Second, the current enlightened view is that addiction is a disease, and diseases are not the kind of thing one has control over or responsibility for getting, or not getting, or un-getting. Since addicts are not responsible for having the disease of addiction, the thinking goes, they should not feel shame, nor should others make them feel ashamed or blame them. We don’t blame people for getting COVID-19, the flu or brain cancer, and feeling shame for getting these diseases seems irrational.

Both arguments need nuance. The shame of addiction often does make sense – and it can be therapeutically useful. Furthermore, addiction, if it is a disease, is not the kind of disease for which experiencing shame makes no sense. Let me explain.

According to anthropologists and cultural psychologists, every culture ever studied uses highly arousing negative emotions – anger, guilt, shame, fear, sadness – to teach its values, norms and practices. These emotions are negative in the simple sense that they have negative valence. They feel bad. This doesn’t mean they are bad. Shame (along with guilt) protects a culture’s values, and a culture builds a self-regulating conscience or a sense of appropriate shame among its members. The self-regulation is key: if one accepts certain norms but is tempted to violate them, one experiences anticipatory shame that, at its best, catches people up short of doing what they think they ought not to do.

Most kinds of shame do not involve a negative global evaluation of the self. If a parent says to a child: ‘You ought to be ashamed of yourself for not sharing the blocks with your sister,’ they aren’t inviting the child to experience global shame, to think that he is a bad person. The invitation is to abide by a norm of sharing because it makes games more fun and because that’s what good people do. There are, of course, extreme forms of shame that are weaponised to make people loathe themselves because of unchangeable characteristics – they are perceived as being the wrong colour or shape, or from the wrong place – which is cruel and never justified or helpful. These extreme kinds of global shame are fertile soil for addiction. However, ordinary, everyday shame is not so lethal.

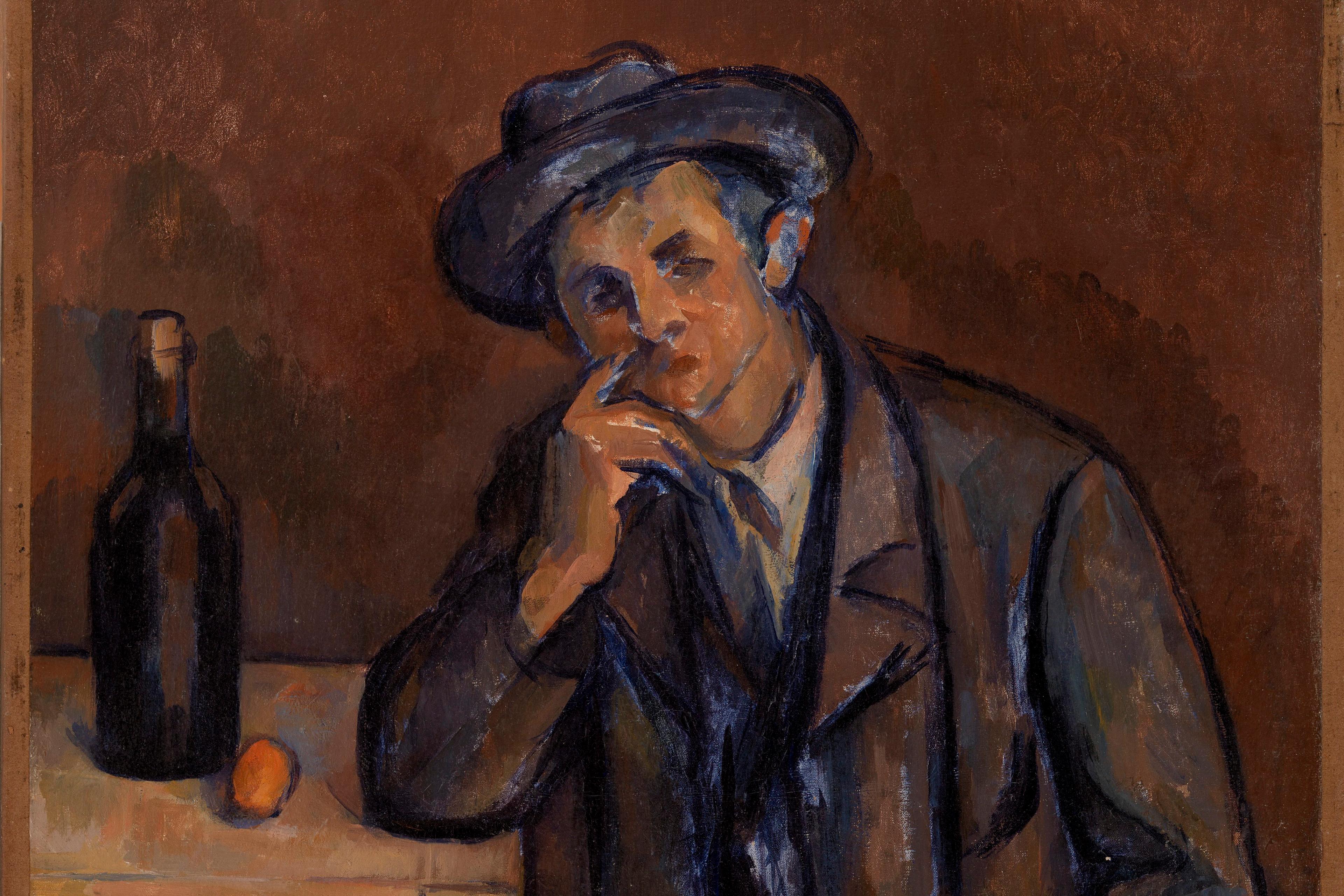

There comes a time when the costs for the addict dramatically outweigh the benefits

Ordinary shame can be informationally rich, in terms of where and how one is failing and might need to step up or change one’s game. It is common to feel shame if one detects that one is falling short of shared values and norms and is consequently perceived as lazy, unreliable, sloppy, socially awkward or dishonest. Socialisation is supposed to work this way.

Here is a very common norm that is protected by shame: do not develop a habit that undermines your ability to live a good life or achieve your goals, or that ruins your most treasured relationships. The norm is general – it could apply to habits such as shirking responsibility at work, stealing, or antagonising people – but it applies especially well to addiction, because addiction is a condition that causes personal distress. There comes a time when the costs for the addict dramatically outweigh the benefits.

The shame of addiction, properly focused, invites the addict to recognise that they were a person before they were an addict – and that they can be that person again, or some new and improved version of that person, if they can find a way to undo their addiction. Three types of failure reliably produce this kind of shame:

- Self-control failure: a loss of control over the substance. The addict tries to moderate or stop using, but can’t.

- Conventional decency failure: the addict displays some degree of difficulty in abiding by the conventional sociomoral order because of their addiction. The addict has a picture of a conventionally decent person, and they want to be one, but they aren’t measuring up. They become unreliable, dissemble and make commitments to themselves and others that they don’t keep.

- Telos failure: the addict has various plans and goals that they want to achieve: finishing high school, becoming a professional basketball player, comedian, firefighter, partner, parent. Besides all the normal obstacles humans face in achieving their ends, addicts often self-undermine due to their addiction.

Shame as a response to these three failures is not global. It is not a negative evaluation of every aspect of one’s being. Rather, it is a perfectly sensible emotional response to failing to abide by norms for a good life that the addict accepts. It warrants shame rather than guilt because addiction involves a habit, a set of dispositions, not only a set of proscribed acts (such as drinking too much).

Some addicts are charmed by their addiction, and experience it as identity-constitutive

Many addicts who experience shame for these three failures are motivated to seek help. In my own case, friends, family and various professionals helped me understand that, despite the way my shame felt at first – like a global indictment of who I was – it made sense for me to feel ashamed only for having perfected a very unhealthy, self-undermining habit. I was a person before my addiction, and the task now was to eliminate the habit without giving up on myself, the person with the addiction. The wisdom in AA and NA meetings often comes around to addicts helping each other experience their shame in this way, in order to keep their eyes on the prize of undoing their habit, without needing to entirely redo themselves as people. We do not tell each other that our shame has no basis, although we often tell each other that global shame and self-loathing are unwarranted and counterproductive.

This process is not always easy. Some addicts started young – early starting age is, sadly, a strong predictor of eventual addiction. They started before they were a fully developed person. These individuals cannot simply be invited to become again who they once were. Other addicts are charmed by their addiction, and experience it as identity-constitutive. They were a person before they were a person with an addiction, but they have trouble seeing how to be that person again and understanding why they should want to. Cases such as these require delicacy, compassion (including self-compassion), sensitivity and wise guidance. In combination with these qualities, addicts and clinicians can still work profitably with shame.

At its best, the shame of addiction is a healing shame. It is focused, not immobilising, and does not embed a desire to punish oneself. It calls the addict to account, but does not involve a negative evaluation of the whole self. The shame of addiction is not normally like the theatrical shame of Greek tragedy. Oedipus can never escape his shame. He did, after all, kill his father, and marry and sleep with his mother. The shame of addiction is different. The addict can normally undo the cause of their shame – the addiction.

Ethically speaking, one should feel shame only for what one can control. This brings us to the second argument against shame in addiction, which relates not to the toxicity and globality of shame but to the fact that diseases are not the kind of thing one ought to feel ashamed about.

Here’s the rub. Every effective treatment of addiction requires the addict to judge their addiction as harmful and to take responsibility for their addiction. Cognitive behavioural therapy assists addicts in identifying patterns in their situations, feelings, thoughts and behaviour that sustain the addiction, and working to undo them. In contingency management, small rewards are earned for abstinence or moderation. Motivational interviewing helps the addict gain insight into their most important aims and how the addiction undermines them. Other approaches include therapeutic communities – often cohousing communities with practices designed to heal the addiction – and group therapy, such as AA and NA. Addicts can also take medications to treat co-occurring mental health conditions, to diminish their cravings or to substitute a safer substance for the addictive one.

Most people who experience shame for their addictions judge it to be a warranted response

When addicts speak of the disease or disorder of addiction, the analogy is almost always to diseases such as type-2 diabetes, where the individual participates to a certain extent (sometimes unwittingly) in the development of the disease. The individual bears some responsibility for developing the condition, and every way out – to remission or recovery – requires a reassertion of responsibility.

Telling addicts they ought not to feel shame for their addiction is a form of gaslighting. The shame is inevitable, given the constant social messages they receive that addiction is not a sensible or worthy lifestyle choice. Again, shame is what you are supposed to feel if you have a trait or habit that is socially disapproved and that undermines your aims for a good life. In my experience, most people who experience shame for their addictions judge it to be a warranted, authentic response to their predicament, and find that that recognition motivates healing.

The upshot is this. Beware of glib statements to the effect that, because addiction is a disease, feelings of shame should have no place in how an addict or anyone else conceives the addict’s plight or way to recovery. Addicts have a host of emotional responses to their plight, and people do them no service by telling them that their shame is baseless. Successful treatments use the addict’s own emotional responses to what ails them to provide reasons and motive for recovery. Insofar as addiction is a disease, it is the kind that one must take responsibility in undoing.