The day I learned my great-grandfather was a killer, certain aspects of my own life became clear to me, snapping into focus with an almost audible click. I grew up hearing that my great-grandfather had been a powerful man who was equal parts obstinate, harsh and unlikeable. But until that day, I had no idea he had also been capable of maiming and killing thousands of people without remorse. As horrific as that realisation was, it was also revelatory. It led me to reflect on the power of addiction and the toxicity of family secrets, what counts as poison and what counts as elixir, and whether and how redemption is possible, and for whom.

Wayne B Wheeler, c1920. Courtesy Wikipedia

I am the great-granddaughter of Wayne B Wheeler, leader of the Anti-Saloon League in the era of Prohibition. While this may sound like a mundane bureaucratic position, Wayne B (as he was known in the family) was no mere bureaucrat. He was passionately, fanatically and obsessively opposed to the consumption of alcohol, and spent much of his adult years trying to eradicate this ‘poison’ from American life.

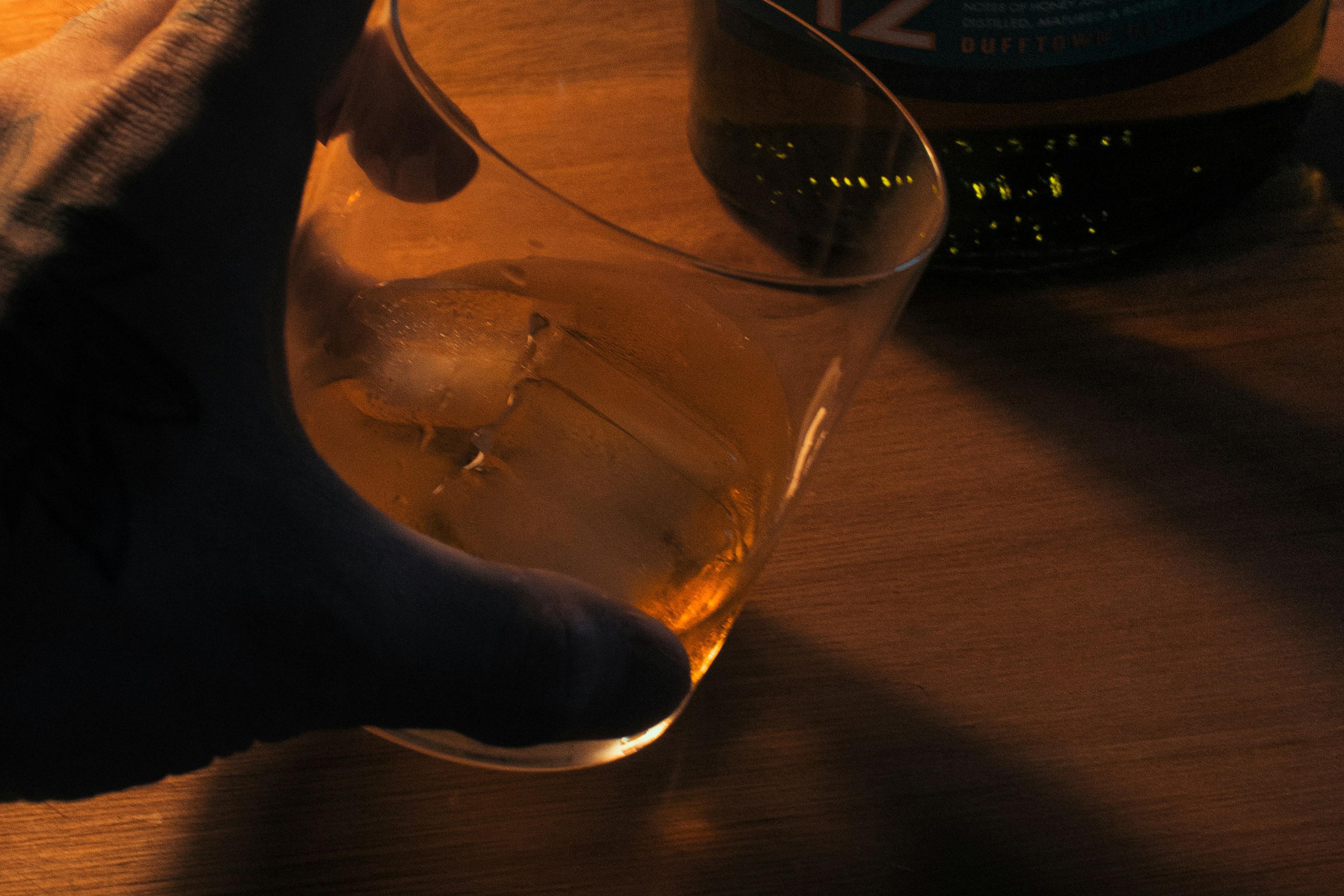

After the passage of the Eighteenth Amendment to the US Constitution banning alcohol, Wayne B, who had championed the effort, expected Americans’ cravings for alcohol to evaporate. But they did not. Bootleggers transported and sold illegal alcohol, speakeasies flourished across America, and people devised ways to distil industrial alcohol to make it drinkable.

In response, the Bureau of Prohibition, under Wayne B’s guidance, decided to try a new tactic. In 1926, they began mixing poison – yes, poison – with industrial alcohol to prevent people from distilling and drinking it. Moderate voices in the anti-saloon movement suggested using non-lethal additives like soap to achieve the same ends, but Wayne B insisted on deadly poison, reasoning that ‘the Government is under no obligation to furnish people with alcohol that is drinkable when the Constitution forbids it.’

During the next seven years, until Prohibition was repealed in 1933, between 10,000 and 50,000 Americans were blinded, crippled or died horrific, agonising deaths from drinking this poisoned alcohol. It was a national catastrophe. News outlets and social service organisations raised the alarm and desperately pleaded for people to avoid distilled alcohol; yet the deaths continued. Wayne B was gratified and unrepentant: ‘The person who drinks this industrial alcohol,’ he reasoned, ‘is a deliberate suicide.’ Wayne B washed his hands of these deaths, comfortable in the conviction that people who drank alcohol illegally and died had simply got what was coming to them.

A hundred years later, when I learned of Wayne B’s poison campaign for the first time, I couldn’t believe what I was reading. I felt sick to my stomach, not only because of the sheer callousness of Wayne B’s actions but also because of my family’s history of alcoholism.

Wayne B had a son, Joseph (Joe) Wheeler, my grandfather. Joe did well in school and later attended Oberlin College. There, he met and married Shirley, a vibrant young woman with a passion for life and a taste for drink. Joe and Shirley settled in Arlington, Virginia where they started a family while Joe’s star rose in the same business as his father: government service. Joe would eventually become consul general of Florence, after a diplomatic posting to Yugoslavia; but in the early years, he worked for the Department of Agriculture and focused on making the right kinds of connections with the right kinds of people.

As was the norm in the professional world of the 1940s and ’50s, Shirley played an important role in Joe’s professional advancement. Planning, hosting and attending social functions were key activities for a diplomat’s wife, and the stakes were high. Before long, however, Shirley’s drinking became something of a concern. Joe noticed that, by the end of a night of socialising, her speech would be slurring. She sometimes didn’t remember conversations she’d had the night before.

By the time I was old enough to form memories of my grandmother, I never knew her not to be drunk

During this time, Shirley and Joe had three children, including Linda, my mother. For many years, the family led a seemingly charmed life of travel and adventure, in several important diplomatic posts around the world. Then, the unthinkable happened. In 1970, Joe Wheeler died at his desk in Florence. Shirley was only 54 years old when she became a widow and, in the wake of her husband’s death, her drinking escalated. Within months, she was drinking every evening.

Over time, ‘cocktail hour’ creeped earlier and earlier, and lasted later and later. By the time I was old enough to form memories of my grandmother, I never knew her not to be drunk. It wasn’t until I was maybe 10 years old that I realised what was going on. It was not a secret – Grandma made no effort to hide her drinking – I just hadn’t picked up on it.

I was about 11 years old when I noticed something else: my mother’s drinking was escalating. Like my grandmother, my mother was a vibrant, outgoing, beautiful woman who loved socialising, dancing and laughing. And drinking. During my childhood, she kept things under control but, during my teenage years, that started to change. She went from drinking socially to drinking on occasional evenings at home. Then she was drinking every evening, like clockwork. Whether or not my dad (a busy physician) was home, at 8 pm sharp, the rum and Coke would flow. It was agonising to watch and painful to live with.

My parents would argue about my mother’s drinking, my dad accusing my mom of being just like her mother, and my mom protesting that he was making a big deal out of nothing. By the time I left for college, I spent as many evenings as I could away from home or hiding in my bedroom.

Two years into college, I got a phone call from my mother. In a shaky voice on the other end of the phone, she told me that she had stopped drinking and had joined Alcoholics Anonymous. From that day until the day she died more than 30 years later, my mother never had another drop of alcohol. She went to several weekly AA meetings and sponsored others, helping them stop drinking, too. Alcoholism, she said, is a disease. Alcohol, for my mother, became a dangerous substance which she avoided at all costs. It was poison. Two generations after Wayne B’s Anti-Saloon League crusades, the family narrative had come full circle.

Given my family history of alcoholism, I view my great-grandfather’s opposition to alcohol as rather grimly ironic. But when I learned about the poisoning and the murders, his unrepentant stance, and the hatred and cruelty he directed toward people susceptible to alcoholism, I began to reflect more deeply on how families – and societies – understand and respond to addiction, and how these responses ripple through generations.

Wayne B never met his daughter-in-law Shirley – he died while my grandfather was still a teenager – and he certainly never met my mother. What would he make of the diplomat’s wife in the neat suit and pillbox hat with her ever-flowing gin and tonics, or the sweet-natured doctor’s wife with her nightly rum and Cokes, both of whom risked their families for alcohol? Would he say they, too, deserved to die?

If I could meet Wayne B today, I would tell him that my mother and my grandmother were good women who loved their families and were doing the best they could with the tools they had. Pain, loss, grief, fear, anger, shame, loneliness and self-loathing – and the desire to lessen the weight of them – are human experiences that have nothing to do with the strength of one’s character or the rectitude of one’s morality. If only Wayne B himself had understood this. In 1927, he lost his beloved wife Ella Belle in a tragic housefire and died the following month, some say of a broken heart.

This attitude towards addiction and mental illness has done – and continues to do – at least as much damage as his poisoned alcohol

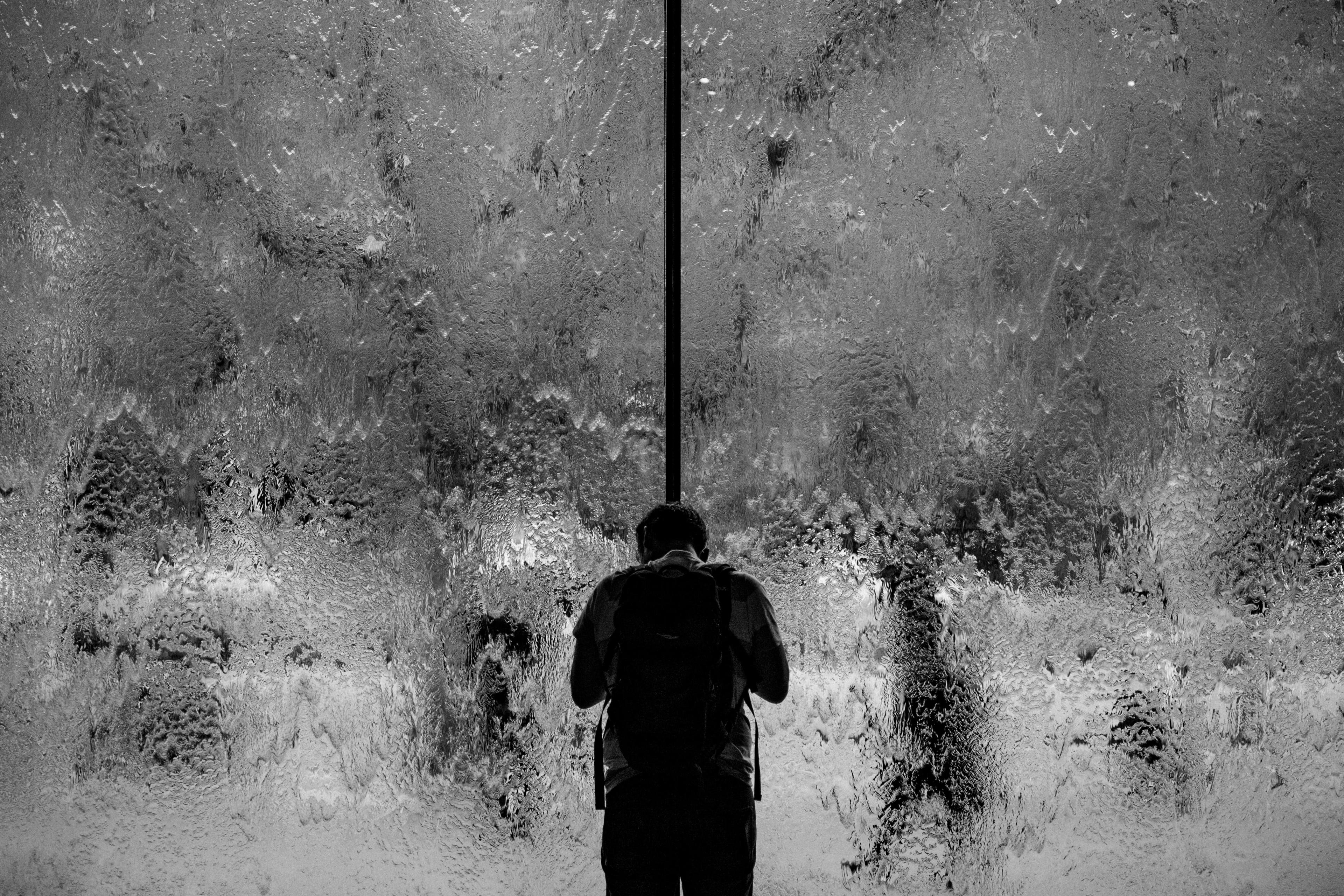

For most Americans, the legacy of Prohibition evokes images of speakeasies, gangsters, rum runners and illegal distilleries. For me, it hits in a more raw, intimate way. It is the story of my family, and how ‘respectability’ and a clean public image offered no protection from private suffering. Wayne B’s story shows that we cannot legislate away people’s pain. We cannot ‘motivate’ people out of addiction or mental illness by withholding empathy, compassion and treatment; if we could, we would have far better outcomes than we currently do.

Recovery from addiction does not follow a predictable path. It is not usually a ‘one and done’ sort of endeavour. Relapse is common, making insurance companies reluctant to fund care for these conditions. Because of this, sufferers are continually challenged to prove their worthiness to receive care – that they have the will, fortitude and desire to transform their characters to become more comfortably predictable and manageable.

My great-grandfather had a hand in legitimising and normalising this attitude towards addiction and mental illness, and it has done – and continues to do – at least as much damage as his poisoned alcohol. Our cultural attitudes toward mental illness and addiction remain as much about moralising the person as they are about targeting a disease.

In recent years, advocates have worked to reframe these conditions as biological afflictions, thereby hoping to transform sufferers into innocent victims so they can be seen as worthy of empathy and care. But this is simply rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic. The problem is more systemic, involving the entanglements of moralised understandings of mental illness and addiction and the for-profit healthcare industry that together benefit from offloading the responsibility for care onto individuals who are most in need of help.