The word ‘economy’ evolved from the Greek root οἶκος. ‘Oikos’ had three interrelated senses in ancient Greece: the family, the family’s land, and the family’s home. These three, taken interchangeably, constituted the first or fundamental political unit in the ancient Greek world, especially in the minds of Greece’s hereditary aristocrats, for whom family mattered more than all other affiliations. The family, then and after, was viewed as the state in miniature, with its rules of order and its exemplars (of moral strength or moral incontinence).

Henry David Thoreau, knowing his Greek, loving puns and etymologies, and being a punctilious writer, was likely quite deliberate in the choice of ‘Economy’ as his title for the longest and first chapter in Walden (1854). By living in his spartan little pond house, his oikos, and getting this house in order, as it were, Thoreau meant to help others get their houses in order – and, house by house, family by family, give new life to society. The dry title hides a pun with a deep purpose, one that whispers: this is a book about a house, a simple one on a pond, but also a not-so-simple one, a disordered one, orbiting the Sun.

Thoreau’s simple furniture from the cabin at Walden. Photo courtesy the NYPL

Thoreau’s purpose at his pond house was akin to the purposes of his contemporaries. While Thoreau’s intellectual compatriots, especially the Transcendentalists, experimented with communal living – for example, George Ripley’s Brook Farm (1841-47) and Amos Bronson Alcott’s Fruitlands (1843-44) – Thoreau experimented with the opposite: solitary living. The scholar Michael Meyer notes this contrast in his introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of Walden, adding that Thoreau’s ‘two-year retreat to Walden Pond was his response to the communal efforts of the Transcendentalists’.

Why so many experiments in living at that time? Why that explosion of new forms of ‘home economics’, communal or solitary? The answer might be related to the fact that the national oikos was divided. Abraham Lincoln’s ‘House Divided’ speech, given 11 years after Thoreau’s last day in his Walden Pond home, and four years after the publication of Walden, confronts the essential fears of this period:

‘A house divided against itself cannot stand.’ I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved – I do not expect the house to fall – but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other.

An abolitionist, Thoreau felt his country becoming all one thing: a nation of slave auction blocks, driven by immoral and insatiable commercial cravings. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, enacted four years before the publication of Walden, required all slaves be returned to their owners, even if the escapee lived in a free state. Effectively, there were no more free states. The house was all one cruel thing now. The federal act, of course, saddled the federal government with its enforcement: Washington, DC became the national slave-catcher.

Thoreau spent a night in jail for refusing to pay a tax to this government; he would not bankroll slave-catchers, nor the unjust war against Mexico. From this brief incarceration, Thoreau wrote one of the most influential political essays of all time, ‘Civil Disobedience’ (1849); Leo Tolstoy, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr, were among those profoundly inspired by it.

Gandhi employed his own modified version of civil disobedience, Satyagraha, to end the British exploitation of the Indian oikos. One example, Gandhi’s powerful 24-day, 240-mile ‘Salt March’ or ‘Salt Satyagraha’ in 1930 , recalls a line in the ‘Economy’ chapter of Walden: ‘Finally, as for salt, … to obtain this might be a fit occasion for a visit to the seashore.’ Gandhi, like Thoreau, understood the potency of personal change – a change at the fundamental political unit: you. Gandhi wrote:

We but mirror the world. All the tendencies present in the outer world are to be found in the world of our body. If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change … We need not wait to see what others do.

Thoreau’s ‘Economy’ asks us to change the American house, if not the global house, by changing ourselves, putting ourselves in order. Think globally, act locally. This is home economics at all political levels. ‘Live deliberately’ – not merely a personal motto, but a social one – exhorts us to wake up, to examine clearly what everyday choices we make, in our home first and foremost, but not only there.

Thoreau’s pond house, by the way, was an open house. ‘I would gladly tell all that I know … and never paint “No Admittance” on my gate,’ he writes in the ‘Economy’ chapter. As Robert Sullivan, in The Thoreau You Don’t Know (2009), reports:

On August 7 of the first year [of Thoreau’s Walden experiment], the Concord Freeman, a local paper, covered the annual meeting of the women in Concord who were against slavery, a meeting convened on the anniversary of the freeing of the slaves in the West Indies. The meeting was held at Thoreau’s house at Walden.

Thoreau likely learned this hospitality from his mother Cynthia, who operated the Thoreau house as a boarding house during the recessed economic period following the Panic of 1837. But Thoreau also learned good housekeeping from another woman, Lydia Maria Child, an abolitionist and an activist for the rights of women and Native Americans.

Child’s modest how-to manual, The Frugal Housewife: Dedicated to Those Who Are Not Ashamed of Economy (1829), opens with a passage that presages Thoreau’s desire to ‘improve the nick of time’:

The true economy of housekeeping is simply the art of gathering up all the fragments, so that nothing be lost. I mean fragments of time, as well as materials. Nothing should be thrown away so long as it is possible to make any use of it, however trifling that use may be; and whatever be the size of a family, every member should be employed either in earning or saving money.

This might sound miserly and profoundly out of tune with Thoreau’s supposed disregard for pecuniary matters. ‘Supposed’, however, is the right word: Thoreau was quite interested in money, in tallying the true cost of things. ‘Economy’ is comprised of lists of figures, such as food and construction costs. These accounting figures are, in part, spoofs of the house pattern books popular in Thoreau’s time, but there is a serious purpose, an aquifer, under the dry details. The messages of Thoreau and Child are in perfect chorus: ‘Waste not, want not.’ As Thoreau tallied them, the necessities of life, the things truly precious to an individual or family, actually cost preciously little.

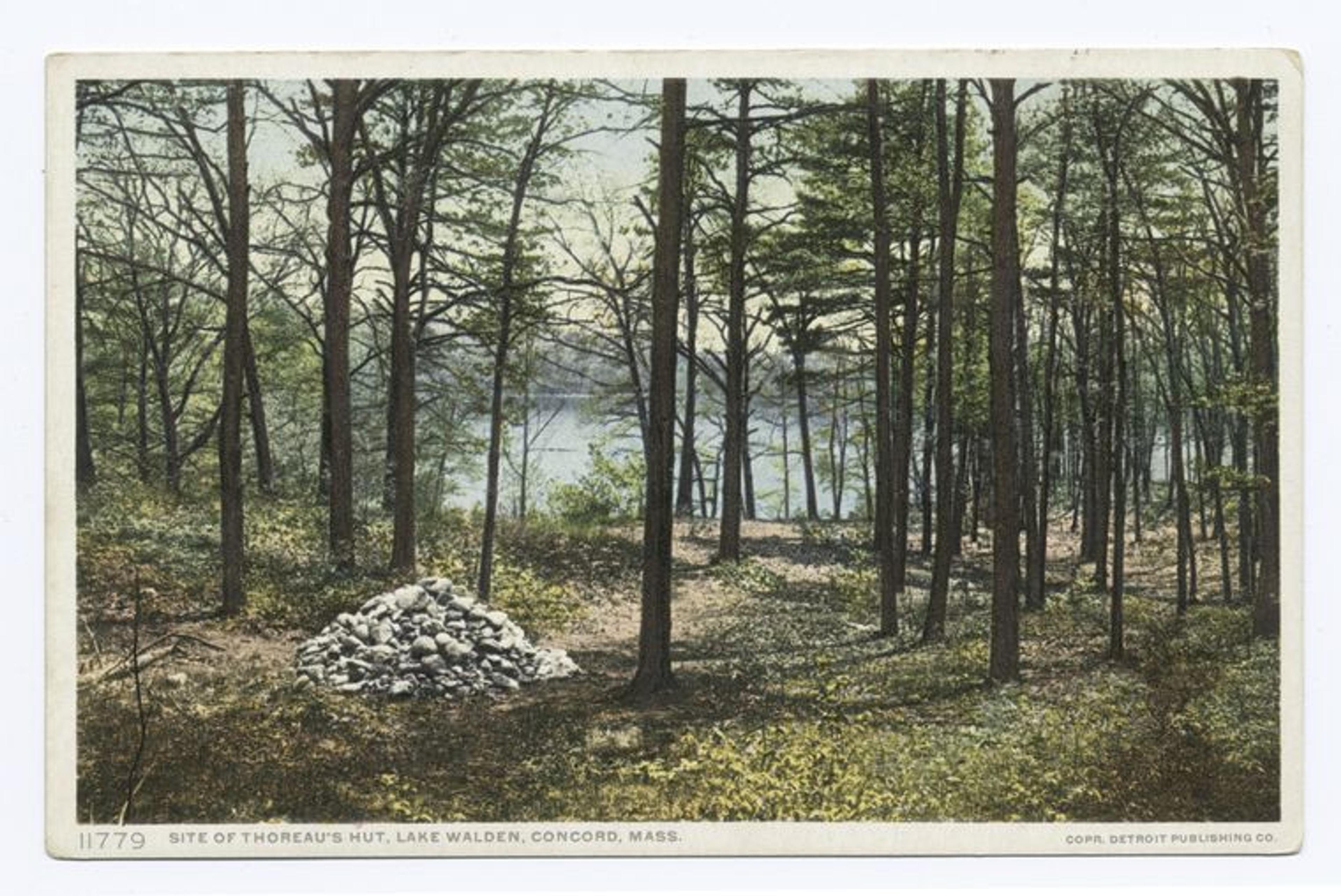

A postcard from 1907-08 showing the cairn location of Thoreau’s hut on Walden Pond, Concord, Massachusetts. Photo courtesy the New York Public Library

Being ‘at home’ with these necessities is key to a meaningful life. As Child put it in an often-overlooked section of the Frugal Housewife centring explicitly on philosophy:

All of us covet some neighbour’s possession, and think our lot would have been happier, had it been different from what it is. Yet most of us could obtain worldly distinctions, if our habits and inclinations allowed us to pay the immense price at which they must be purchased. True wisdom lies in finding out all the advantages of a situation in which we are placed, instead of imagining the enjoyments of one in which we are not placed.

True wisdom indeed, and painfully difficult to gain. One of the ways to achieve this wisdom is to slowly, intentionally, methodically, work with what you already have. ‘The most characteristic mark of a great mind,’ Child wrote, ‘is to choose some one object, which it considers important, and pursue that object through life.’ Marie Kondo’s The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up (2010) reached blockbuster status by way of a similar intuition. There is a reason why the expression ‘paying attention’ makes sense: when we give our attention to our homes, the places where we immediately live, we find that they are worth much more than the places we are not. In ‘Economy’, Thoreau made this point, more pointedly, more than a century and a half earlier.

Why do we say ‘more pointedly’? Because Thoreau never valorised sheer drudgery. He didn’t encourage us to ‘be zen’ about chores that should bore us to death. He encouraged us to live deliberately in light of economic forces, of the forces that will make a house a home – and genuinely our own. Quarantine recently put new emphasis on that home life. Now, in what some call ‘The Great Resignation’, we are, en masse, not returning to the office. We’re staying remote or simply resigning if remote is not an option; we’ve staked our pond houses and now, perhaps, we mean to live deliberately.

So let’s not squander that which is absolutely precious, the time that we still have. Make decisions about how and where to tap meaning. That is the paramount economic skill. Do not covet the farms and mansions owned by the Joneses of your neighbourhood; acknowledge the prices they have paid for owning them. And notice that you have friends at your modest fire, and a roof over your head, and stars above, and say a little prayer to the minor deities of home-economy.