Back then, eight years ago, as I stand in the living room of my childhood home on top of three-foot piles of musty clothing, used tissues, empty yoghurt containers and plastic Barnes and Noble bags full of actual shit, it doesn’t occur to me immediately that this all adds up to a story. A story that explores how this could have happened in my family, about how I grew up and saved myself and, later, untangled my guilt and self-recrimination, a story about loss and redemption. What emerges from the clean-out of my mother’s hoarding creation is not only a book, but a metaphor for the writing process itself.

Like the disorder necessary in a writer’s rough first draft, objects from my mother’s life, our family’s life, are thrown around in the tsunami inside her 1970-era, split-level home. Her preoccupations are evident in what she’d saved: empty sea shells, thousands of pennies that might be valuable to a coin dealer if they turned out to have a rare defect, books about places she’d visited – Scotland, China – or would like to go to, framed pictures of some people (but not all the people) she cared about, gifts for her children and grandchildren she’d purchased but that, by the time the holiday or event happened, couldn’t be found in the sea of garbage she was adrift in.

Rough drafts are about accumulation, about preserving things without fully understanding what might be useful to create a world for the reader: bits of dialogue, witnessed scenes, stray memories that emerge into consciousness. All the lost things washed up and needing to be picked through to find only what is most meaningful to help the reader connect to the plot. As I shovel down, with a real shovel, through detritus layered like a dirty torte, damp with mould and pressed together, at the bottom was lost jewellery. An antique ruby ring my mother used to wear that had been my grandmother’s, a pin stuck to a torn sweater I almost tossed before seeing the gold glimmer. I saved these valuable objects that would become metaphors for my family saga, deepening the story.

After the rough draft comes the story’s structural scaffolding that’s necessary for the reader: descriptive information about a character, historical facts, a timeline of events, motivations. A second draft is about deciding what to keep. It’s writer’s intuition, but also, in my case, having trust in my own process born from years of writing in my journals. I find an old turn-off notice, evidence there had likely been no water in my mother’s house for at least six years. I hold on to this as evidence of the truth, although I would likely never need it. There are practical items I think my mother would want that help me make sense of the emerging story – the old green datebook with her important phone numbers, tax forms for the various nursing jobs she held, and every photograph, even if the picture is damaged. Wet corners curled from the flood coming through the kitchen ceiling where the roof had been left unrepaired. For how many years? Five? Twenty-five? Maybe for the whole 30 years that I had not been inside, while she was accumulating this mess.

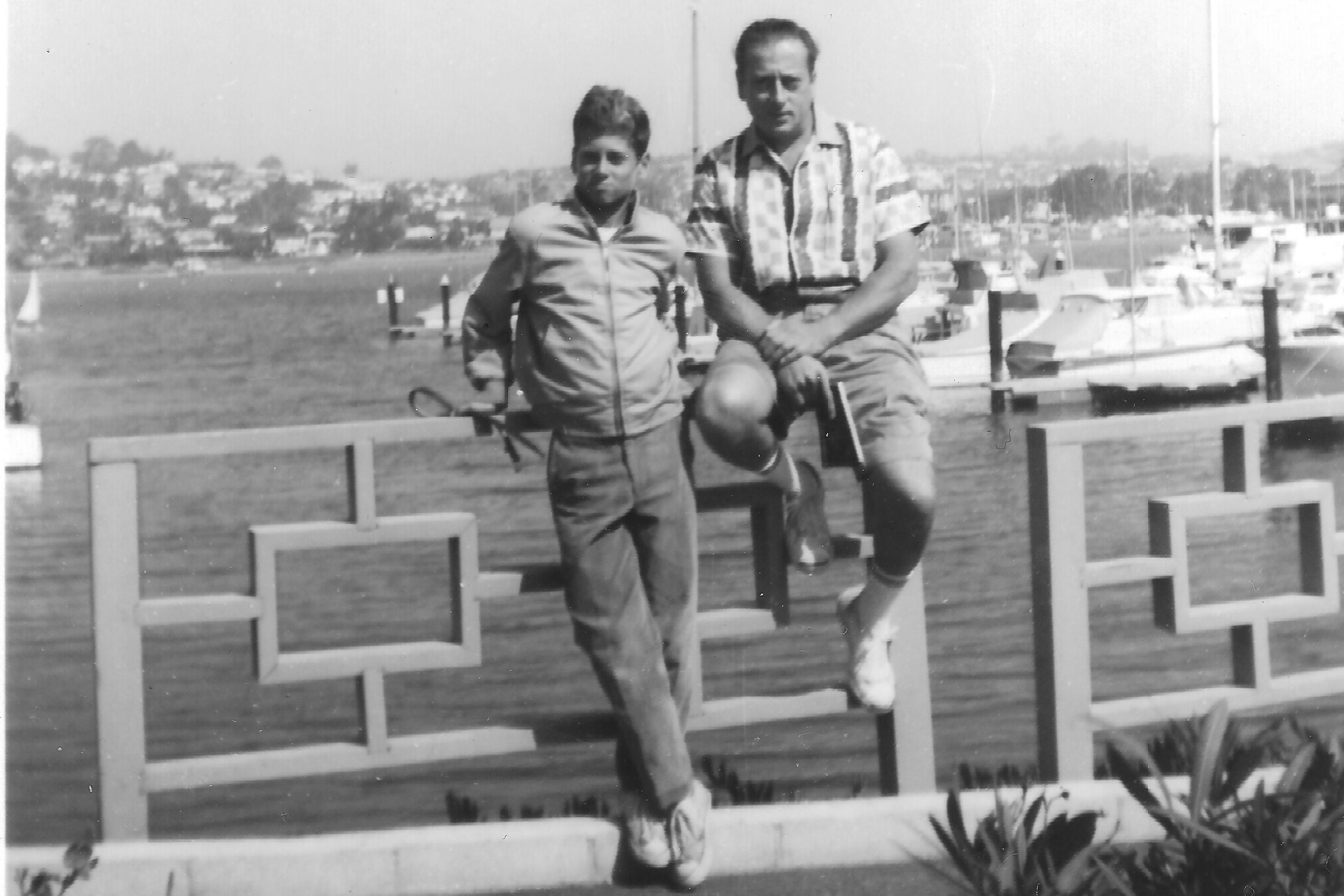

I rescue every photograph, even if I don’t know the people pictured, but especially if I do.

I am salvaging all my family history. Even if it seems irrelevant. Even if my mother seems to have stopped caring about it. I tuck quotes she’s scribbled in her cramped handwriting on scrap paper into a bag for safekeeping. Perhaps these are key themes for this story. I discover them like pottery shards from an archaeological dig – lines of poetry she liked from T S Eliot, a description of space from Einstein, the same Louise Penny quote that also struck me as meaningful from the book I loaned to her and she never returned: ‘There are four things that lead to wisdom … I don’t know. I need help. I’m sorry. I was wrong.’

As I empty each area of the hoarding house, the task becomes making meaning by connecting things in a linear way. Themes and stories are linked one to another like the long spaghetti tangle of clothes and trash and hangers I pull up from the floor. Here are childhood books I read, the stuffed tiger I played with, now eaten by mice. Here’s the tableau of little gifts for my sister’s birthday, evidence of my mother’s thoughtfulness. Here is the purple silk dress my mother wore to my wedding, happy that I’d found a husband with whom I shared a career and intellectual interests, and who had a wicked sense of humour. Here are some things my mother bought for herself to use once she was ‘organised’ – the decorative lamp for the home office where she would write in the mostly blank journals I found, the never-used suitcases for those dreamed-of future travels. Her story and my family’s story emerge, one excavated room at a time.

There are also good memories in these cleared-out spaces. Remembering my high-school graduation party in the backyard, dancing to Saturday Night Fever and going to sleep afterwards in the antique bed she’s strewn with dirty clothing I’ve now bagged to throw away. These too are segments of the narrative.

I’m editing my mother’s shame into 325 black contractor bags

The plot unfolds. First, she picked a house. She had a husband, a daughter, another husband, another daughter. Then she decorated her home with care and with the objects she wanted – a sofa in her favourite colour of light blue, the ‘good’ Danish dining room table that she saved to purchase when she first married my stepfather, her mother’s silver to use for holiday meals, real artwork on the walls. But then things got lost. My grandfather dies, she and my stepfather divorce, my sister and I grow up and leave the house. There’s more room in her story, but she found herself filling the space with other things – loneliness, paranoia, fearful thoughts inside old imaginings, old holiday decorations, more books, the garbage that became the physical evidence she existed. Then her critical and difficult mother dies. My mother neglects the house. There’s the leaky roof, the overgrown yard, the paragraphs that go nowhere until she is trapped in her recliner with a phone that works only sometimes when her children try to reach her.

It’s me, my sister and our husbands who deal with the mess in my mother’s house. I make chapters from the chaos, understanding how my own story makes even more sense than it did before, knowing all this. I’m stacking each page with my memories, some of them triggered by the objects I’ve rediscovered that will now fill my own house. I’m editing my mother’s shame into 325 black contractor bags containing parts of her life, my adolescent life, so heavy the sanitation department sends three men and a special highway trash truck to pick them up. I’m cutting and shaping the story to fill a 30-yard dumpster and a 20-yard dumpster with my old art projects, drawings, hammered-tin flowers, sewn needlepoint things that smell and are ruined. In draft after draft, I try to make sense of all of this, making it whole.

We move my mother to a studio apartment in an assisted living complex, too small for her to hoard much. She’s angry, ashamed and won’t explain any of it. All she wants to know is whether I threw out her favourite family picture of my grandmother with the goat, her most loved artwork that hung askew in her old living room, and the antique Chinese porcelain urn that meant so much to her. My mother never asks me if I am writing about her creation – what she ended up neglecting, the house, herself, me, by leaving me with everything she claimed to care about. But she is my ideal reader, asking about the details of the objects, wanting to understand the things that resonate for her. She is the one who I want most to understand my story, to connect with me through my writing about what all of this means.

But, seven years after we clean out the house, she will die suddenly, two months before my book on the excavation finally sees light of day. I can only go back and forth between what I remember and what I held on to from the clean-out. This is what I lost, what you lost, Mom, and what I found. You are the story I kept.