Since the millennium, there has been a huge increase in the visibility of philosophy, both online and off. There are, of course, books on philosophy, but also numerous popular live events, courses, podcasts, television and radio programmes, and newspaper columns. Philosophy today is as likely to be found on YouTube as it is in a bookshop or library. Just to mention a few examples of freely accessible online public philosophy initiatives: Michael Sandel’s ‘Justice’ course, the BBC’s History of Ideas animations, or the many popular philosophy podcasts, including History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps from Peter Adamson, Philosophy Bites from David Edmonds and Nigel Warburton, and the philosophy episodes of the BBC Radio 4 series In Our Time. This complex and heterogeneous phenomenon is generally called ‘public philosophy’. It’s philosophy done in public rather than behind the doors of seminar or lecture rooms, or in paywalled academic journals.

‘Public philosophy’ seems at first glance to be what Ludwig Wittgenstein dubbed a family resemblance term. He used the example of a game to illustrate this concept. Just because we call something a game doesn’t mean that it has some essential feature that all games share. Wittgenstein maintained that, often, there are simply resemblances between the things we call by the same name, just as there are shared and overlapping physical characteristics that run through a family related by blood, but no single visible defining feature. Similarly, one may think that perhaps there’s no one essential quality that all public philosophy has but, rather, there is a cluster of important features that the many examples of it have in common.

In the case of games, the philosopher Bernard Suits in his book The Grasshopper (1978) argued that Wittgenstein was wrong. There was in fact something that all games shared, namely that they are voluntary activities in which players attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles. You could simply walk and place the golf ball into the hole with your hand, but instead you have to abide by the rules of the game, which means you have to hit it there with a golf club.

Although philosophy itself is very difficult to define, it is less ambitious to look for what all public philosophy, or at least all good public philosophy, has in common. I want to argue that public philosophy can and must be identified by its purpose. We should ask the question ‘Why do we engage in public philosophy?’ in order to answer the question ‘What is public philosophy?’

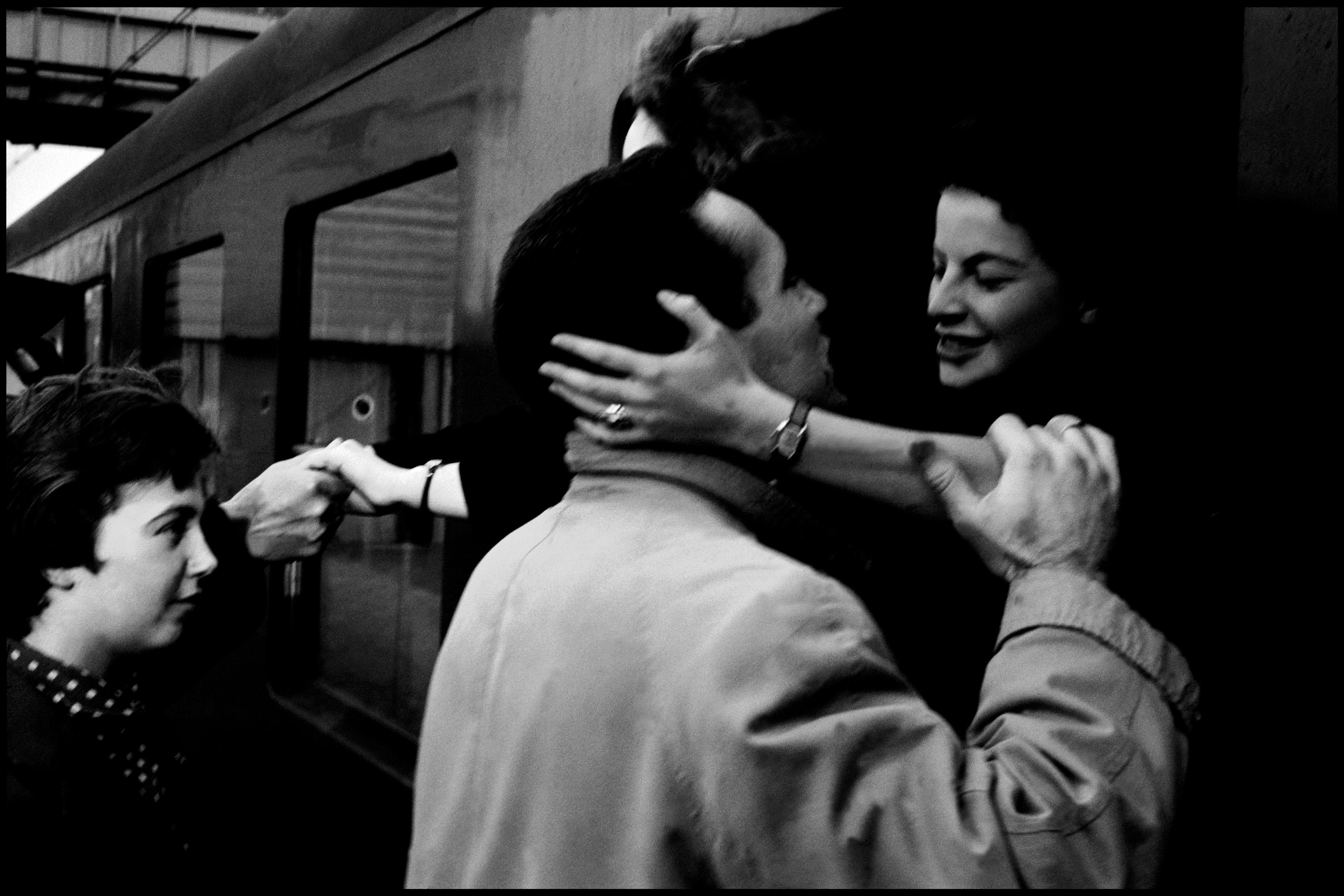

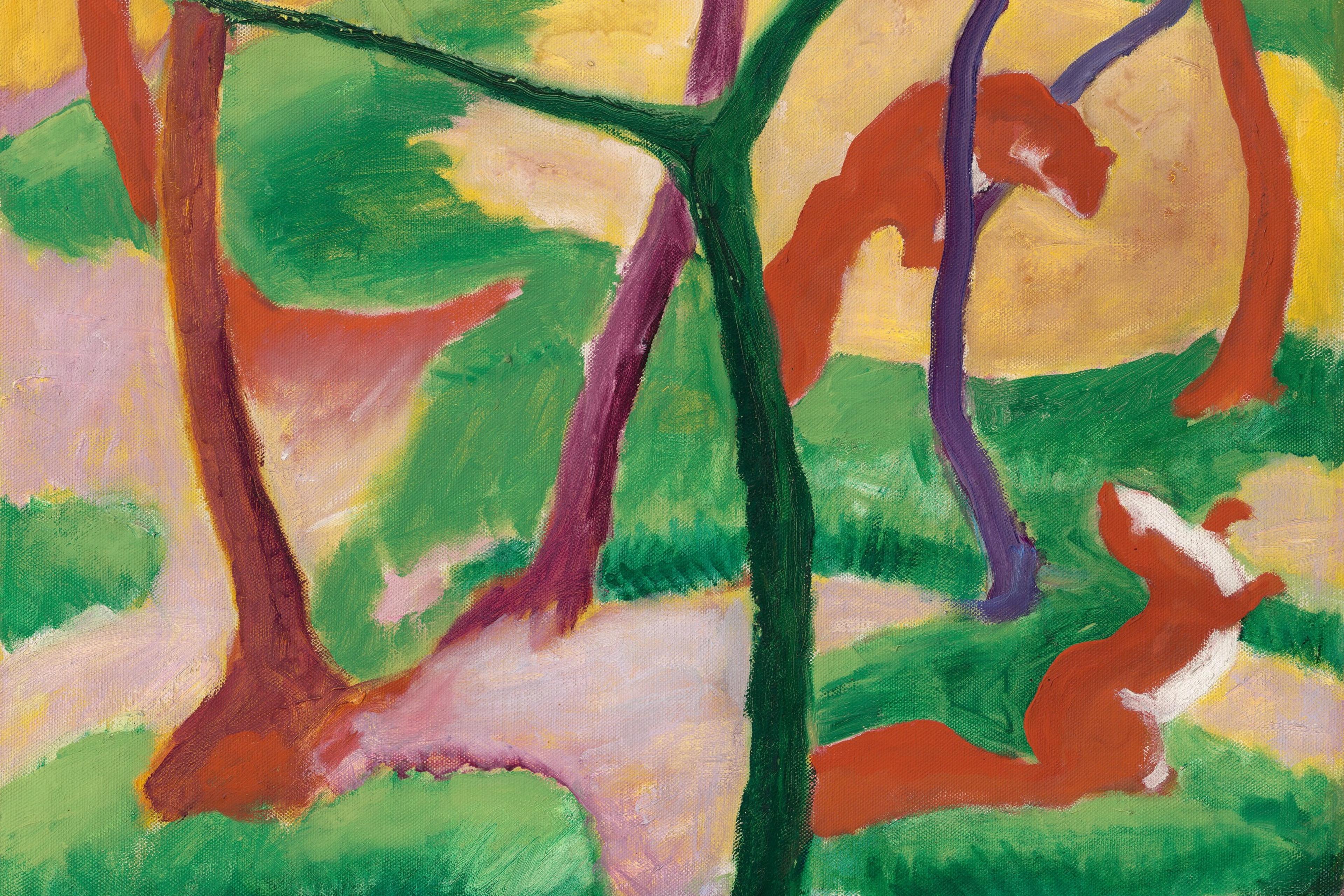

After my PhD and postdoctoral research in philosophy – I was interested in G W F Hegel’s philosophical psychology and his theory of knowledge – I felt the urge to bring philosophy to places it hadn’t yet reached. I wanted to put my expertise in the field at the disposal of those people who might be interested in philosophy and yet who hadn’t had the opportunity to study it. So I organised and promoted what I call ‘philosophical labs’ and public philosophy initiatives in northern Italy, where I live, and online. In a philosophical lab, the public is invited or, better, provoked to think, discuss and reason about a chosen issue together. You may want to use different kinds of stimulus to provoke the public to philosophise: it can be a passage from a philosophy text, or a thought experiment – like those presented in the bestseller The If Machine (2nd ed, 2019) by Peter Worley – but also a case study from the news or a work of art. Almost anything can provide the pretext of a thought exercise. After giving the public the stimulus to think about a controversial issue, and letting them express their immediate opinions regarding it, the philosopher invites everyone to think again and to think better.

Like Socrates, who walked through Athens disturbing his fellow citizens with his questions and forcing them to review their opinions in order to evaluate their consistency and possible implications, public philosophy is a practice that, as it were, ‘disturbs’. It forces the audience to reflect critically on what they thought they knew. The philosopher helps the process of investigation by demonstrating underlying distinctions and connections (conceptual analysis), by revealing implicit assumptions, and by letting possible implications of a given thesis emerge. The ideal outcome would be for everyone to actively participate in the process of rational investigation (thereby exercising some specific cognitive and argumentative abilities), and to achieve a more profound understanding of the examined issue.

By organising and hosting philosophical labs for very different audiences (from children to the elderly) and in very different contexts (from schools to prisons), I always had a sense of what I was doing and why. Whether we were discussing the notion of truth, or beauty, or happiness, I knew that I wasn’t trying to formulate a new angle or a distinctive critique. The difference compared with what I did as an academic researcher was certainly clear in my mind, and yet I would still consider both kinds of activity as ‘doing philosophy’. In both cases, I was engaged in reasoning and reflection, and yet they were not the very same action. There is something that distinguishes public philosophy from other forms of philosophical practices.

I have since then reflected on this and have come to the conclusion that public philosophy should not be defined and recognised by its object, nor by some specific employed methodology, nor even – as is often suggested – by its accessible language, but essentially and exclusively by its purpose.

Often – it is said – what distinguishes academic from public philosophy is the intended target. Public philosophy is philosophy undertaken in public venues, addressed to a nonprofessional audience. However, this definition in terms of its audience is still too general and says too little about the nature of this practice. Introductions to a philosopher or a philosophical issue are also meant for a nonprofessional audience, and yet they are not examples of public philosophy in the strict sense I’m outlining here. They differ regarding the educational purpose they want to achieve.

Public philosophy is best understood as an activity that aims to promote rational thinking in anyone it can reach. Public philosophy is a catalyst to thought. Its goal is not to disclose the results of the philosophical tradition or research. At least not exclusively, and not primarily. Its main aim is to introduce the audience to the philosophical practice of thinking critically: that is, to the problematisation of the given, the critique and analysis of a question, and to a dialectical confrontation. The purpose of a public philosophy initiative is to show thinking and dialectical strategies, along with the results they produce. As the philosopher Jack Russell Weinstein put it in 2014: ‘My first rule of public philosophy then, is “let them see you think”.’

If we understand and conceive of public philosophy in this didactical function, we can also better understand its relationship with academic philosophy.

One of the main objections to public philosophy is that it makes philosophical theories and concepts banal and simplified, and thereby betrays the professional and scientific status of the discipline. Every scientific discipline – it is argued – has its degree of necessary specialisation and complexity. No one pretends to make virology or molecular biology perfectly accessible to everybody (at least that was true before COVID-19 in the social media era); why insist on doing the same with philosophy?

Hegel, annoyed by the presumption that everyone could philosophise, took much the same line. He didn’t want to defend an elitist vision of philosophy; instead, he emphasised the need for a proper training course in order to exercise a rational, philosophical way of thinking. What Hegel, along with many contemporary critics, meant is that the activity of doing philosophy is not something we are immediately capable of – it demands training and rigour.

Good public philosophy actually accepts and implements this very vision of philosophy as a rigorous practice of thinking. Precisely because it does not take it for granted that certain cognitive capacities (such as the ability to analyse, conceptualise or criticise, etc) are naturally and equally developed by everyone, one of its aims is to stimulate, guide and exercise them.

Academic research is primarily devoted to reaching a better understanding of its subject of investigation. The purpose of public philosophy is different. While I engage in a discussion about truth and falsehood with a nonprofessional audience, I do not aim to produce a brand-new more exhaustive definition of ‘truth’. My purpose is to guide the public to better understand their conception of truth, to permit some unreflected assumptions to emerge, and possibly point to how some philosophical research impacts on the topic. Public philosophy does not compete with academic philosophy, and it doesn’t vulgarise the subject. It is, rather, an invitation to think philosophically. By making conceptual and operational tools available to all, philosophy becomes public in the full sense of the term.

Taking this approach answers the question of why philosophers engage in the practice of public philosophy. And yet, someone may still ask: why do you do that? Why should philosophy aim to introduce people of every age and occupation to the practice of rational thinking?

The ultimate legitimation of public philosophy is based on a metaphilosophical assumption that cannot be taken for granted and isn’t universally accepted: the belief that thinking philosophically or rationally has a value in itself.

This is a very ancient idea epitomised by Socrates and Plato before many others. It is the conviction that promoting rational thinking will allow people to read reality better, both in terms of understanding themselves (their aspirations, desires, limits and potential), and the world they inhabit. This improved awareness will affect people’s personal lives, but also the whole community, insofar as rationality, argumentation, constructive disagreement and continuous research are understood to be prerequisites of a participative citizenship in a liberal democracy. This is a strong assumption on which not everybody agrees. It maintains that rationality can overpower prejudices, misinformation, fallacious reasoning and gut attitudes, ultimately supporting a pacific, well-informed dialogue and conflict management.

Today we are aware of the role played by cognitive bias in our judgment to trust philosophy to produce a miracle. We see how public opinion is more and more polarised, misinformed, influenced by irrational beliefs, and how public dialogue can be dominated and silenced by poorly argued slogans. These phenomena have always existed but have been recently sharpened by the contemporary dynamics of information. They inevitably raise the question whether our societies are still grounded in a rational exchange of ideas, and whether the mission of public philosophy is vain and naive after all.

Few public philosophers are under the illusion that their activity will transform the general population into lucid, rational and well-informed citizens. Public philosophy is not some kind of panacea. But I do believe that, despite all contingent and historical difficulties or our personal weaknesses, rational thinking has a key role to play in society, and that philosophers can stimulate meaningful public conversations about what really matters.