When I was 14, I learned that my father had another name. Among the Spanish speakers of the Río Grande Valley of New Mexico, whom he’d lived alongside as a young adult, he had been known, he told me, as Rafael El Manco, ‘Ralph the one-armed’. He had lost the limb to an accident as a child. The name was a sign of affection, an indicator that he was welcome in their world. To me, it was a vestige of his earlier life, a sign from some mysterious world beyond the desert in which I grew up.

We lived out on the western edge of the state, in the alkali flats they call the badlands, between the Navajo Reservation and the territory of the Utes. It was a land of wind and dust. Our town was tiny, 2,500 people, dominated by the Right-wing John Birch Society and the Baptist Church. Our place was a cramped duplex next to the trailer park. As an amputee with no real education, my old man struggled to hold down a job. But he often talked of his younger life, and his English was shot through with phrases from the Spanish-language world he had known before he went broke and moved us west. ‘Espérate,’ he would say to slow me down when I grew frustrated trying to use his carpentry tools. ‘Qué bueno,’ when the work was good.

The Spanish novelist Miguel de Cervantes had a moniker like my dad’s. He was called El Manco de Lepanto for having lost the use of one of his arms at the battle of Lepanto, in 1571. Cervantes went on to write Don Quixote, the greatest of all European novels, composed, partly, in debtor’s prison. My father never spent time in prison, but he had plenty of money problems. He was a cowboy, raised on a ranch, but because of his disability he was unable to flourish in the American West. I never saw him read a book. The blockbusters popular in those days – 800-pagers by Irving Stone and Leon Uris – were difficult for him to hold in his one hand. But like Don Quixote, he dreamed of a world beyond the badlands, where his imagination could set him free from poverty and from the phantom pain that still pulsed in his amputated arm. But he had been through high school. He read the newspaper everyday. And his written English was good. So, one day he decided to write a novel of his own. He wanted to tell a story about the Río Grande Valley where he had once lived, a true tale of ethical, laconic cowboys, Native hunters and Mexican migrants.

During one of his unemployed stretches, he got out the old black manual Royal typewriter and set it on a little grey gun-metal table, carefully threading two sheets and a slice of carbon paper into the platen with his good hand. He sat there all day, tapping away with three fingers and his thumb, like a telegraph operator along the old route of the Pony Express.

I never saw what he wrote. But after months of writing, he sent it off to a publisher in New York. He never heard back.

Most of my friends’ fathers had come to New Mexico to work in the nearby gas fields. They spoke with the scraping drawl of West Texas and Oklahoma. But I sensed that my father’s quixotic dream of another life was somehow rooted in his Spanish-inflected speech. So, when ninth grade rolled around and we got the chance to pick an elective in our studies, I chose Spanish. Our roots were over on the Río Grande, after all, and this, for me, was the real New Mexico, with its history of the Conquistadors, of Taos Pueblo, of the beautiful Santa Fe plaza and the cathedral, of the holy sanctuary at Chimayó, where the penitentes marched once a year and whipped themselves for their sins.

On the first day of Spanish class, we sat silently in a circle on folding chairs. No teacher was to be seen, but then in strode a small man in a garish orange-and-blue V-neck pullover. He walked around the room, babbling incomprehensibly at the top of his voice, then stepped up onto a folded chair. Raising his arms like an orchestra conductor, he began repeating the same two words over and over: Buenos días.

Areas of my body that I had never felt before were opened up and brought into use

By the end of the hour, we knew how to say it, and a few other phrases as well. Within a few weeks, we had all become different people. We had no labs, no book, no tapes. Just Mr G—, who gave us verbal forms to internalise and manipulate. We mimicked his gestures, laughed at our mistakes, and earnestly asked each other for directions to the nearest restaurant. The performance of Spanish took us out of ourselves. If my father was Rafael El Manco, I became Timoteo. My capacious memory swept up vocabulary and sprinkled it back out in sentences of my own devising. The thrill of mastery brought delight.

The encounter with another language was a great awakening. This is what the study of languages does – it wakes people up. As the smallest and youngest boy in my class in a hardscrabble town, I spent my days being bullied. When Spanish touched my tongue, I began to see a version of myself that I wanted. I sensed that I could become someone else, and how I could become someone else. I hated the tiny town, squatting in the dust, waiting to blow away.

But there, in that language, I was no longer the clumsy, overly talkative, smart-aleck son of the town amputee, who lived near the trailer park. I left myself and that world behind.

Spanish ran through me with a strange kind of sensuality. Language is erotic. Areas of my body that I had never felt before were opened up and brought into use: the letter L slipped from the back of the mouth to the tip of the tongue, delicately, almost seductively; the rolled R imposed a straightening of the spine and a raising of the shoulders; the diphthong – soy, aire, biografía – unfolded sinuously, eliciting a twisting of the upper body. And the rhythm of sentences produced a buzz in the nervous system. I trembled at the romance of it. Spanish rippled through the flat nasality of our sound world, leaving traces of its passing in our muscles and nerves.

But the changes were not simply emotional and physical. Learning Spanish opened me, a 14-year-old kid in a desolate community, to a new way of approaching my life. In my town we were taught that what you learned in school came innately. You were either ‘smart’ or ‘not smart’. You were good at sports, or you weren’t. This is the message that is transferred tacitly to young people in conservative societies like the one I grew up in: people are born certain ways. You grow up to step into those shoes, to go to that church, to find a mate from that community. If your old man drives a Ford pickup or smokes Marlboro Reds, so will you. But now I saw that if I listened carefully and exercised my memory, if I mastered the forms, I might fly. One day I would gloriously rise above the tiny town and my father’s pain, and sail away on a torrent of words.

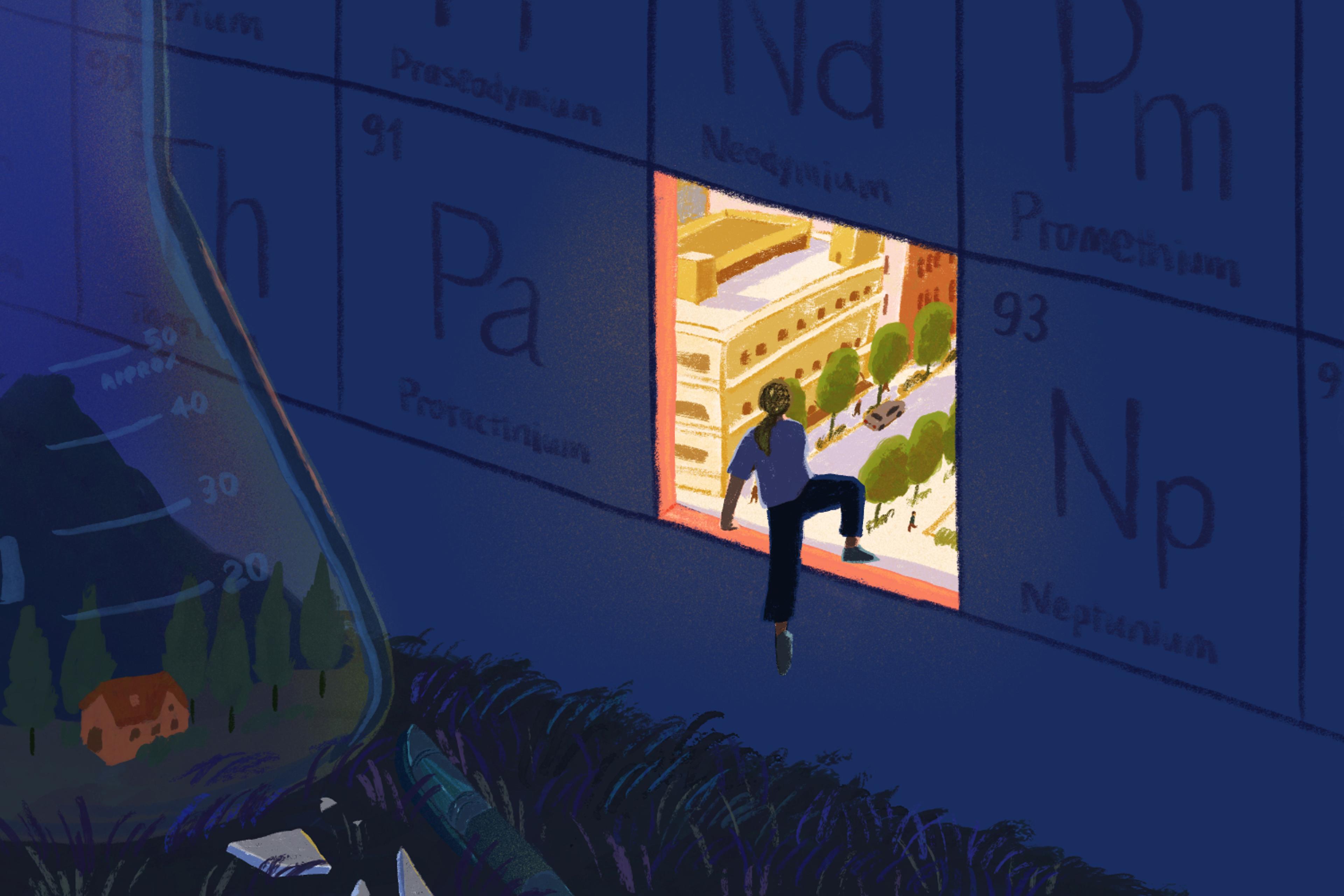

So, for the first time, I became an active learner. I realised that my job was not to sit in class and write down what I was told. That part was easy. My job, the hard work, was to take into myself something new, to seize forms of knowledge that would make me a different person and give me a new life. Language frees you, after all, and it is free to all.

This is why universities, which claim to want to open doors for their students, are foolish to shut down language programmes. Between 2016 and 2021, more than 900 college language programmes closed in the United States alone – an astonishing eclipse of opportunity for poor students. Languages are one of the transformative tools of the liberal arts, and they prepare the mind for all kinds of learning, in all kinds of disciplines. They put students, by virtue of their very structures, in the shoes of someone else. They teach empathy, inscribing it on the body. In my case, they broke open the conservative monolingual world in which I grew up and led me to meaningful work in public education, where I have the good fortune to teach Don Quixote.

Like any emissary from the gods, Mr G— delivered his message and went on his way

I only ever heard one song about learning another language, an old border ballad called ‘Spanish Is the Loving Tongue’:

Spanish is the loving tongue

Soft as music, light as spray,

’Twas a girl I learned it from

Living down Sonora way.

It’s about a cowboy, like my dad, who rides south to Mexico and falls in love with a beautiful Mexican girl. She teaches him a bit of Spanish, so that when he is forced to leave town after a bad poker game, he can bid her farewell by moonlight in her own tongue, Adiós, mi corazón. It’s an old story, mysterious and beautiful – like the novel I imagine my father tried to write.

My dad never left the little town, but Mr G—, the Spanish teacher, moved on. He had ambition. He wanted to earn a certificate to teach bilingual education and for that he needed to return to university. He transferred out, and was replaced by an Anglo woman who could barely speak the language. Like any emissary from the gods, Mr G— delivered his message and went on his way.

But life on the frontier is dangerous. Five years later, when a bilingual teacher was killed in a town down by the Mexican border, we knew who it was even before he was named in the papers. He was shot by the husband of a female colleague in the school, just before class. The killer fired six bullets into his body.

Now, you can’t know what motivates one man to shoot another man, out of the blue, one day, before school, in the room where his own wife works. But no one puts six bullets into another man’s body because of a bent fender or an outstanding loan. One bullet, maybe; not six. There’s only one explanation that makes any sense. Spanish is the loving tongue.