Are human lives worth living? And, if so, is life worth living unconditionally – or are there conditions attached? The philosophical debate about these profound and uncomfortable questions has a long history, going back to ancient Greek and Roman philosophy. Much of what the ancients had to say about these issues is bound to alienate a modern audience. And yet, by reckoning with their views of the life worth living, we can not only better understand how the ancients saw the world, but also find a probing angle to engage with our modern intuitions about these controversial questions.

To start with, it is useful to distinguish between two levels of philosophical discussions about the value of life. On one level, we can ask whether human life is valuable in the sense of having inviolable moral status: life is worth living always and unconditionally. The claim of there being such a status is often invoked by the opponents of abortion or capital punishment. On another level, we can ask whether, or when, a life is worth living for the person who lives it (or who is to live it): when does one feel like their own life isn’t worth continuing? These two evaluative perspectives on life are independent. They can agree or conflict with one another. One may believe that terminally ill patients ought to stay alive and yet maintain – without inconsistency – that their life is not worth living for them.

As for the latter evaluative perspective – whether a life is worth living – many people nowadays would say that the conditions of having a life that’s at least barely worth living are not particularly hard to meet. A life does not have to be great; perhaps it suffices when it is not too bad. According to an influential view in medical ethics, continued existence is worthwhile for a patient if only they desire to carry on living. The view that the criterion for a life worth living is located in the subjective preferences of the person living that life was memorably captured by William James: ‘Be not afraid of life. Believe that life is worth living and your belief will help create the fact.’

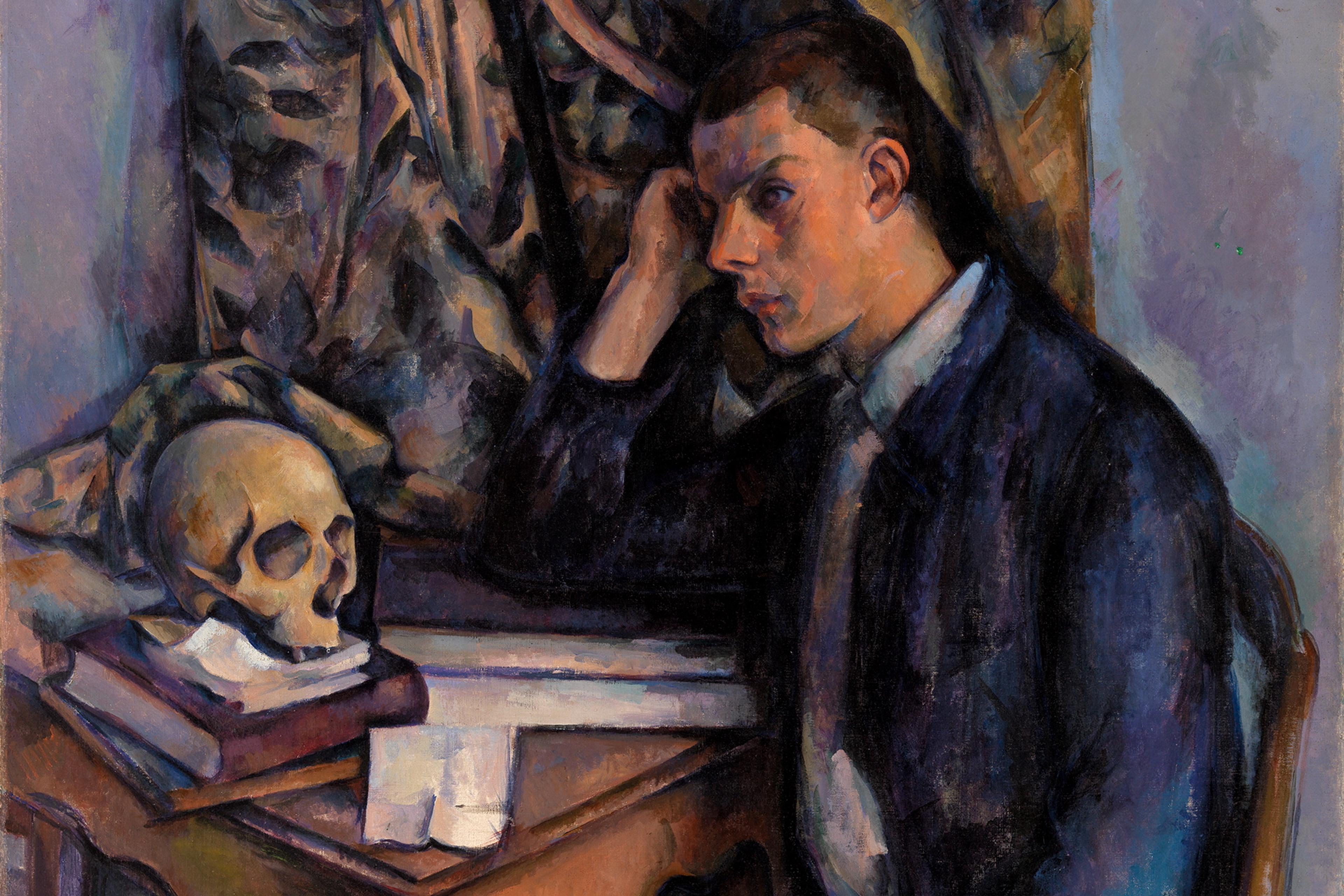

But for ancient philosophers, including Socrates, Plato, Aristotle and the Stoics, this is merely wishful thinking. What makes a life worth living, on the prevailing ancient view, is a degree of life’s objective perfection – a view that is likely anathema to modern sensibilities. This is the outlook that underlies Socrates’s dictum from the Apology that an ‘unexamined life is not worth living’. A human life doesn’t have to be excellent, and it doesn’t have to be the life of a philosopher, but it must exhibit some level of reflection on how one should live and why.

A more radical statement of the perfectionist outlook can be found in the Aristotelian view that ‘good humans should stay alive even in bad fortunes, whereas bad humans should flee life even when fortunes are good’. If your character and intellect are irreparably corrupt, you should hasten to exit life no matter what other goods, including bodily health, you may happen to enjoy. The reason is not that you do not deserve to live, from the legal or moral point of view, but that such living is bad for you – whether you are aware of it or not. Most bad humans in good fortunes no doubt do believe that their life is worth living for them. But this belief simply does not create the fact.

To the modern ear, these views and their consequences sound problematic, even deluded. Some contemporary philosophers have criticised Socrates’s claim as harsh and elitist. Why should the activity of philosophical reflection, rather than plain satisfaction with one’s life, be the decisive criterion for having a life worth living? Should we really give birth only to children who will have a decent chance to reflectively engage with the conduct of their lives? It is hard to imagine how this view could become a basis for any viable governmental policy concerning procreation. The consequences of the second claim mentioned above are even more worrisome. Imagine a medical team denying life-saving interventions to an otherwise healthy person because this person is morally corrupt. Surely, we demand, the quality of one’s character should be categorically excluded from bioethical deliberations of this sort.

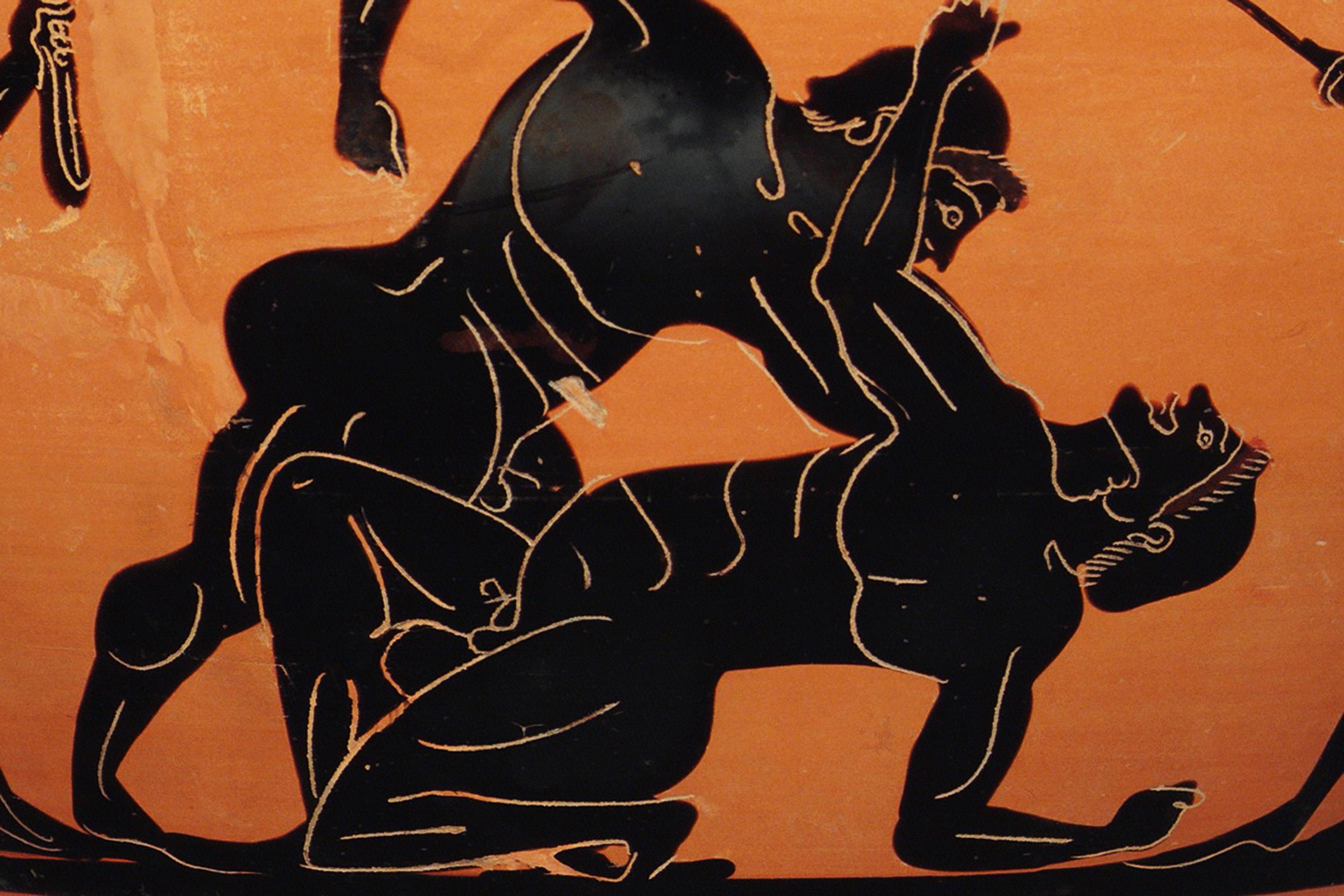

So, according to the ancient philosophers, it takes more to have a life worth living than most people nowadays, including philosophers, are inclined to grant. A possible response to the ancient outlook is to dismiss it as a function of cultural and social idiosyncrasies. One can point to a general life-pessimism characteristic of ancient Greek culture, as exemplified by Sophocles:

Not to be born is, beyond all estimation, best; but when a man has seen the light of day, this is next best by far, that with utmost speed he should go back from where he came.

This pessimism, in turn, may reflect prevailing religious views or healthcare available at that time. Do these idiosyncrasies not seriously limit the extent to which ancient views can be philosophically viable options for us today? But there is also a more attractive line of response: to focus on the arguments of ancient theories that do have a more universal philosophical validity. In the ideal case, these arguments enable us to draw important lessons from ancient philosophy that may encourage healthy σκέψις (scepticism) towards some entrenched modern intuitions.

The key to a sound assessment of ancient views is to appreciate that perfection is understood in terms of fulfilment of function. The insistence that a life must have a degree of intellectual and moral perfection amounts to the view that a life cannot be worth living unless it enables us to fulfil our natural functions, both biological and social, and in that sense allow us to live up to who or what we are. From this perspective, humans are not at all different from other living things. Imagine a caged eagle that is well fed but cannot freely fly and hunt. Many would agree that a life is not worth living for this bird, given how impoverished, even humiliating, its existence is. The eagle may wish to stay alive, as long as it is well fed; but that just does not make its life worth living.

What flying and hunting are for the eagle, reflection and morality are for humans. What is distinctive for humans as a biological species is a wide range of psychological capacities under the ambit of ‘rationality’, ranging from the capacity for speech to the capacity for intellectual reflection or for doing good things for the sake of their goodness. And so those humans who do not ever reflect on their way of life, or those who are corrupt, are like caged eagles: having such impoverished lives, they are a pitiable lot. The fact that they are not aware of their misery does not diminish but rather exacerbates our pity for them. The assessment of a life’s value is always relative to the natural function. The captive life is not worth living for an eagle, but it might be worth living for two caged love-birds. Similarly, Socrates says, an unexamined life is not worth living for humans, but perhaps it might be worth living for a jellyfish.

Is this emphasis on function precisely what we nowadays find unattractive? From the functionalist perspective, the value of life seems to be unduly instrumentalised. This concern becomes more pressing when we move from biological to social functions. In the ancient context, the latter functions were often regarded as extensions of the former: by nature, we are social beings, and hence it is natural for us to adopt social roles and contribute to a wider community. In the Republic, Plato exemplifies this approach towards a life’s worth through the attitude of a sick carpenter. This carpenter would see a doctor only to recover and resume his work as quickly as possible. But if the treatment makes him unfit for work, he would rather say goodbye to the doctor than prolong his life. In assessing the value of his life, the carpenter prioritises his capacity to be of use to the polis. As a general principle, this is worrisome: should we measure the value of our life by our capacity to be an efficient producer?

It is easy to dismiss the implications of Plato’s view as cynical, inhuman or life-denying. But perhaps the lesson is not so much that a human life lacks unconditional value, but rather that there are things in life that are more important than life itself. For the carpenter, it is his work – a vocation – that is a major source of life’s meaning. He loves his work and does it well; it has defined his life to the extent that further existence is not even conceivable without it. His role as a carpenter is also the way that his life is embedded in social structures, and the contribution to these structures is what makes his life meaningful. So functions can be regarded not as vehicles of instrumentalisation but of integration. They define how an individual life fits into the fabric of reality, and thus make a life meaningful. Just as the social functions integrate us into the social context, so the biological functions integrate us with the broader context of nature and cosmos. Similar to plants and animals, which contribute in their peculiar way to the cosmic order, humans, too, have a role to play.

For the ancients, it is the quality of life – in the sense of the ability to fulfil one’s biological and social functions – that determines whether a life is worth living. Some aspects of the ancient outlook can seem to us extreme. But compared with the range of positions in the contemporary philosophical discourse, the ancient philosophers were in fact moderate. On the one hand, no ancient philosopher was committed to the view that every human life has unconditional value. The ancients would regard unconditional life-affirmation as an expression of the unhealthy human tendency to cling to their lives at all costs. On the other hand, and despite the prominent life-denying strands in Greek literature, ancient philosophers did not develop an anti-natalist agenda. Human lives have a decent chance to be meaningful, and thus worth living. To be worth living, a human life need not be either agreeable or perfect: it suffices that it does not blatantly betray one’s station in society and the Universe at large.