An elderly couple anguish over what to buy their son, who lives in a sanatorium, for his birthday. He suffers from ‘referential mania’, believing that everything that happens is a ‘veiled reference’ back to himself. For this character in Vladimir Nabokov’s short story ‘Symbols and Signs’ (1948), the clouds in the sky, stains and pebbles all communicate messages that he has to interpret. ‘Everything is a cipher and of everything he is the theme,’ wrote Nabokov. ‘He must be always on his guard and devote every minute and module of life to the decoding of the undulation of things.’

Nabokov was describing an extreme case of apophenia, or the tendency to experience events as meaningful, even when they shouldn’t be. Also called patternicity, ‘it refers to essentially anytime that you are seeing patterns in the world that don’t exist,’ says Colin DeYoung, a professor of psychology at the University of Minnesota.

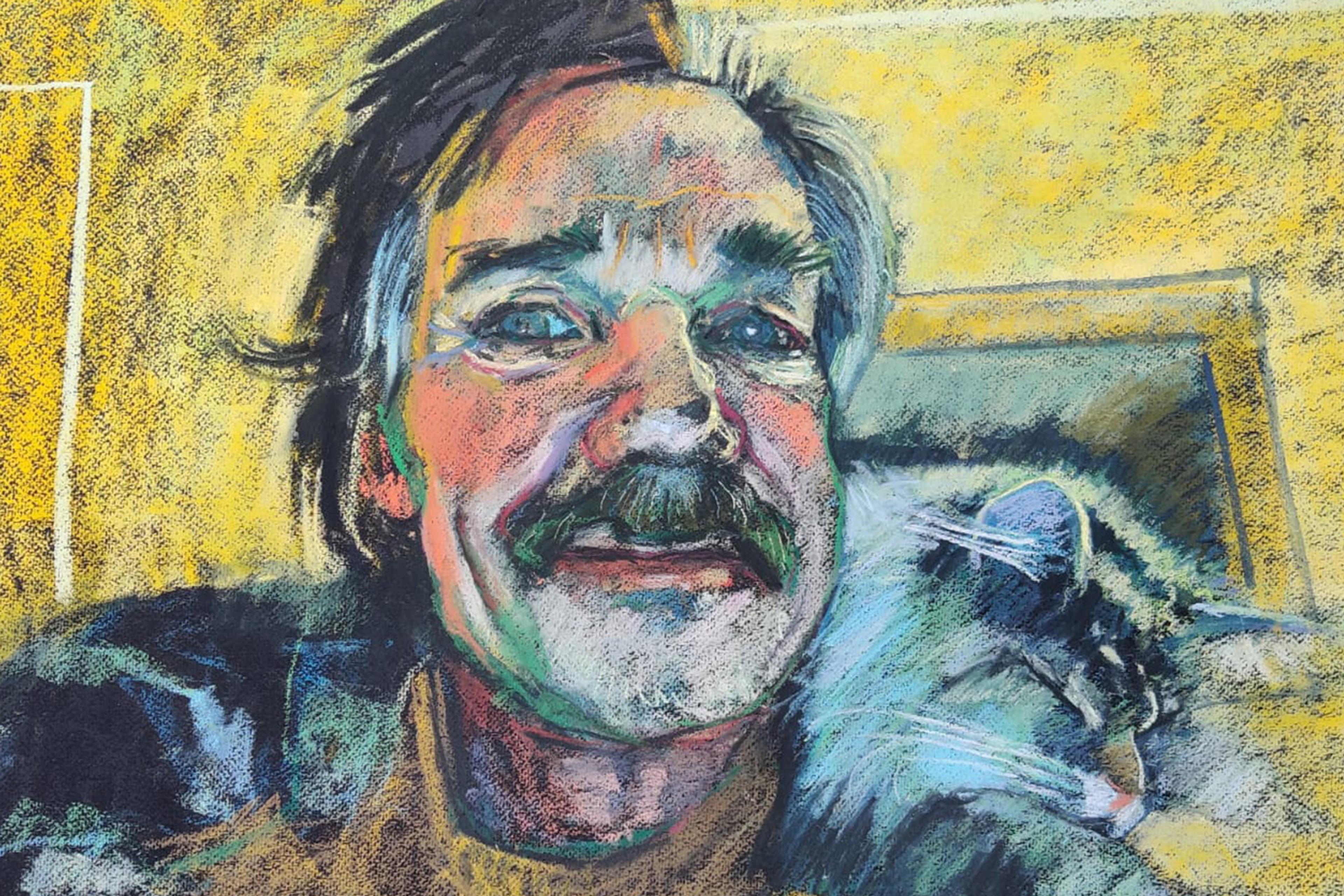

While apophenia is apparent in symptoms of psychosis – hallucinations and delusions – it is a quality we all share, to varying degrees. When someone lies on the grass and looks up at the clouds to find shapes, they are intentionally engaging in apophenia. One specific form of apophenia, based on visual perception, is pareidolia: seeing faces where there are none, in inanimate objects such as electrical outlets or bell peppers.

Apophenia is the cognitive tendency that helps explain Rorschach tests, sports superstitions, astrology and decisions like selecting birthday numbers for a lottery ticket. Understanding how universal it is – but also the fallacies it can lead to – can help us think more critically about the elements of the world around us and how they might (or might not) relate to each other.

The word ‘apophenia’ comes from a German neurologist, Klaus Conrad, and his 1958 book about the symptoms of schizophrenia. While an epiphany is a sudden realisation of a true connection or meaning, an ‘apophany’ is the false realisation of one.

The psychoanalyst Carl Jung used what is perhaps a better-known term, ‘synchronicity’, to describe instances of apparent connection between co-occurring events with no clear causal relationship. More than just coincidences, they take on powerful meaning in a person’s mind and appear to be a result of more than chance. In one example, Jung’s patient dreamt of a golden scarab and, as she described the beetle, Jung heard a tapping on the window of his office. There, he found a live scarab beetle, which he grabbed and handed to her.

Apophenia might make you more susceptible to what researchers call ‘pseudo-profound bullshit’

Psychologists have found an association between apophenia and openness to experience, one of the ‘big five’ personality traits. Openness to experience reflects a general tendency to be curious about the world. As a 2020 paper by DeYoung and colleagues explained, one aspect of openness to experience ‘encompasses fantasy-proneness and aesthetic interests’, whereas another aspect, sometimes called ‘intellect’, reflects ‘intellectual confidence and intellectual engagement’. In many contexts, openness is beneficial and can contribute to creativity. But the component of the trait related to aesthetic and fantasy engagement also seems to be associated with increased risk of some of the symptoms of the psychosis spectrum, such as unusual perceptual experiences, DeYoung and colleagues have found. They report evidence that apophenia could be ‘an important cognitive mechanism at the core of what is shared between openness and risk for psychosis.’

Seeing connections all around you can also be predictive of belief in conspiracy theories and the supernatural, a study from 2017 suggested. People who tend to see patterns where there are none, such as in random coin tosses or certain kinds of abstract paintings, are more likely to believe in well-known conspiracy theories, says Karen Douglas, professor of social psychology at the University of Kent. And, apophenia might make you more susceptible to what researchers call ‘pseudo-profound bullshit’: meaningless statements designed to appear profound. Timothy Bainbridge, a postdoc at the University of Melbourne, gives an example: ‘Wholeness quiets infinite phenomena.’ It’s a syntactically correct but vague and ultimately meaningless sentence. Bainbridge considers belief in pseudo-profound bullshit a particular instance of apophenia. To find it significant, one has to perceive a pattern in something that is actually made of fluff, and at the same time lack the ability to notice that it is actually not meaningful.

Apophenia could even negatively affect decision-making: a 2017 study found that some people began to detect illusory patterns when guessing what colour light would shine in an experiment. Those same people started to think that the lights flashing weren’t a product of chance, but were determined by their previous guesses, even when told otherwise. This pushed them to make guesses that ended up having lower probabilities of being right.

Still, people everywhere exhibit apophenia, every day: they see shapes and faces on the Moon, the image of Jesus Christ on a piece of toast, and the Virgin Mary on a grilled cheese sandwich (which sold for $28,000 on eBay). And, of course, gazing at clouds or relishing small coincidences doesn’t, in itself, mean you’re at risk for psychosis, DeYoung says.

In statistics, there are errors called Type I, or false positives, and Type II, false negatives. People who are high in apophenia make more Type I compared with Type II errors, DeYoung explains: they’re more likely to detect a connection when there isn’t one.

Humans make predictions about the world in part by picking up on patterns

Events that appear unusual may occur more often than we might think, as the statistician David Hand wrote in The Improbability Principle (2014). ‘If you told me beforehand that you would regard seeing a cloud that looked like Einstein as unusual, and then one appeared, that would be remarkable,’ Hand tells me. But just happening to observe a cloud that resembles any shape, including a man with unruly hair, would not actually be that rare – even if it feels that way.

When confronting the feeling of apophenia, these are important nuances to remember: both that seemingly unlikely events are often more common than we assume them to be, and also that we’re primed to notice apparent connections. ‘We are alert for configurations which are meaningful to us,’ Hand says. ‘This is a natural and necessary consequence of our evolutionary history.’ Humans make predictions about the world in part by picking up on patterns; it’s just that some of them are real, while others are illusory.

Nabokov’s short story is filled with details of various events that occur as the parents travel to meet their son and then return home. Their train is delayed, a tiny bird falls from its nest into a puddle, a young girl calls their house, but has dialled the wrong number. The reader is being invited, or challenged, to confront the symbols in the story – while also being told that the son, with his delusions, has been over-reading such signs.

There is always a trade-off. People need to be able to detect important connections in the world, rather than missing them, and being sensitive to patterns helps with that. People who are high in openness and more prone to perceiving patterns ‘might see things that other people might not notice’, DeYoung says. But sometimes, a sensitivity to patterns can fool us. Minimising the risk of the false positives would inevitably lead to more false negatives, DeYoung notes: ‘You’re always stuck with some kind of balance.’