Among the many consequential decisions judges have to make, they weigh in on parole requests: determining whether an individual will regain freedom or remain confined to a prison cell. Several factors normally play a role in these rulings, such as the risk of recidivism, the severity of the crime and the inmate’s behaviour. However, when a group of researchers analysed the decision-making patterns of Israeli judges, more than a decade ago, they noticed something peculiar. The judges released many people at the beginning of the day. But as the hours passed, they became stricter. As lunchtime approached – and the judges presumably grew hungrier – they barely granted anyone parole. Then, after a meal, they became more lenient again. While the conclusions of this ‘hungry judge’ study have since been critiqued, it prompted further consideration of the extent to which justice might depend on extraneous factors such as food breaks.

Are judges human? This is the question posed in 1931 by Jerome Frank, one of the most prominent legal scholars of the 20th century. In the 19th century, when the modern judicial system was taking shape, it was widely assumed that well-trained judges, given the same facts and laws, would consistently arrive at the same verdicts. Anything else would be irrational and contradict the core principles of justice. For many, this belief endures even today. However, modern psychology highlights that judges and other courtroom decision-makers are all too human and might not be as objective as once thought. Factors such as the defendant’s appearance, the weather or even unexpected sports events might influence how cases are decided.

I am a lawyer, as well as a person-centred consultant and behavioural analyst. I observe that legal professionals often fail to recognise the psychological forces that could be driving their decisions. What I’ve learned from the research to date has reshaped my own thinking about the risk of irrelevant influences in legal cases – and how a lawyer might do their best for a client anyway.

Consider some of the red flags that have emerged from research on judicial decisions. One of these findings relates to a phenomenon you might be familiar with: when someone flips a coin, they expect heads and tails to balance out. If heads comes up four times in a row, people tend to believe that tails is more likely to appear next (even though it’s no more likely than it was on the first flip). Our minds, wired to understand the world through cause and effect, struggle to predict truly random events. This tendency, called the ‘gambler’s fallacy’, is something the roulette table exploits. But what does it have to do with judicial decision-making? Well, there is evidence that US judges handling asylum cases make a similar mistake. A judge’s ruling in this context determines whether an asylum seeker will be deported and potentially sent back to a life-threatening situation. Nonetheless, judges were more likely to either grant or deny asylum depending on their previous ruling. After a ‘bad’ case, they seemed to assume the next one was more likely to be ‘good’.

What people see on the television before the trial might also influence someone’s legal fate. In France, research has suggested that criminal courts, in which lay juries participate in sentencing decisions, tend to hand down longer sentences when national television broadcasts crime-related stories the night before. On average, the following day’s sentences were 26 days longer for each prime-time news story about crime. Crime stories might decrease people’s sense of security and bring criminality to the forefront of their minds. Conversely, after reports on judicial errors, sentences were shortened by 40 days, suggesting that media coverage of criminal justice issues might sway jurors to either lengthen or shorten sentences depending on the narrative presented.

High temperatures may simply increase irritability, leading some judges to be less sympathetic

Research has uncovered other odd findings. For example, a study using data from 5 million French court rulings found that judges were more lenient when delivering a verdict on the defendant’s birthday. Social norms reinforce the expectation of favourable treatment on one’s birthday, and perhaps this pressure is so strong that even judges are affected.

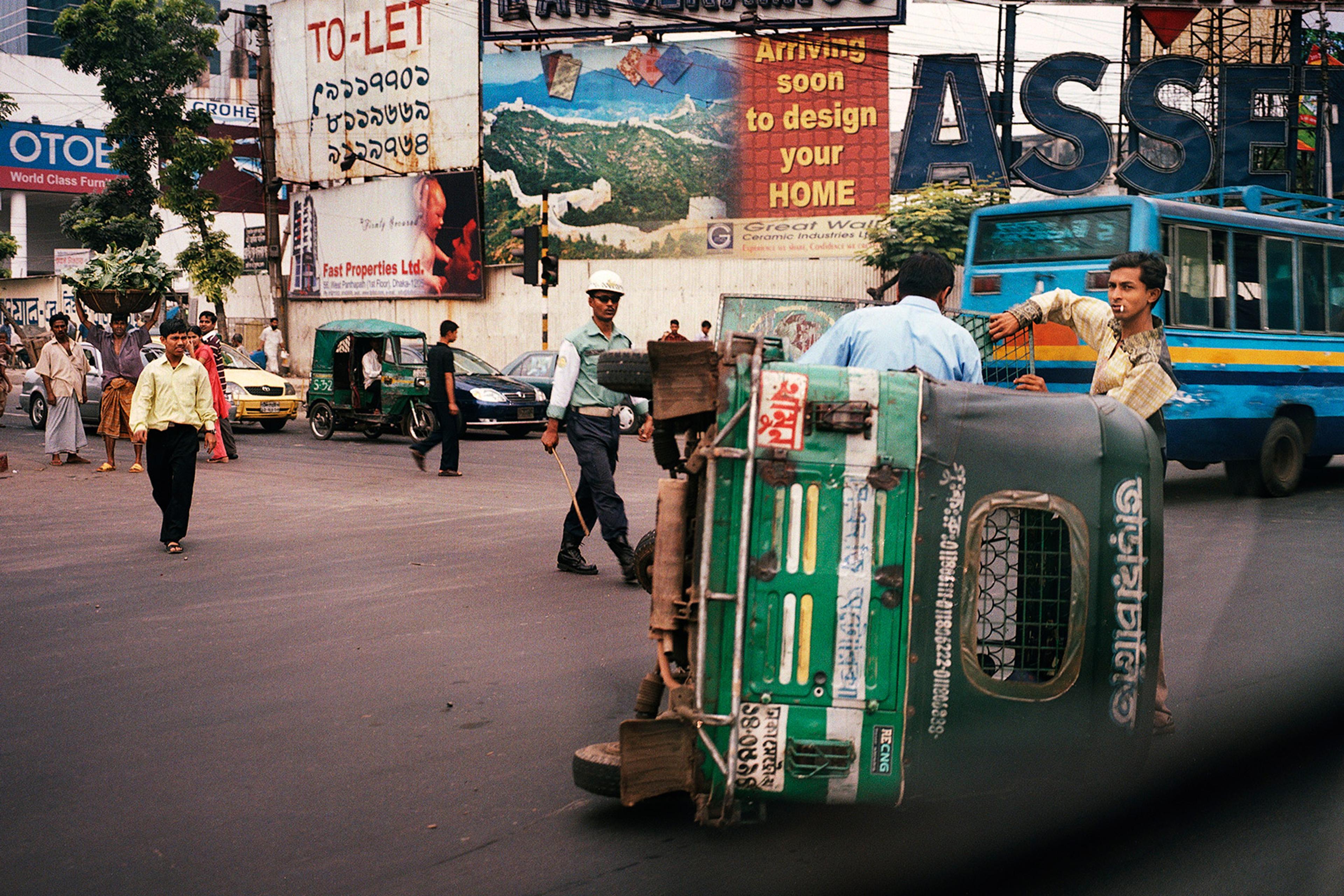

Weather undeniably influences psychological processes. Everyone has experienced it: sunshine can lift your mood, bad weather can bring you down. Surprisingly, studies in both India and the US have found a relationship between warmer weather and harsher court rulings. Researchers are still exploring possible psychological mechanisms behind this phenomenon. High temperatures may simply increase irritability, leading some judges to be less sympathetic toward petitioners. Alternatively, hot weather might result in behavioural patterns that differ from cold days, in turn affecting judicial performance. For example, judges may be less inclined to take breaks in fresh air during hot days.

Findings such as these suggest that even highly trained legal actors cannot entirely detach their decision-making from trivial influences unrelated to the case at hand. Upon further reflection, these may not even be considered very significant distractions in the grand scheme of life. It is likely that other random factors – such as family issues, personal joys or fluctuations in health – have an even greater effect on a legal professional’s state of mind, subsequently influencing the outcomes of cases. If there were data on these aspects as well, the workings of the justice system might reveal itself to be more chaotic than it currently appears.

Lawyers and defendants cannot change the weather, but they can attempt to understand the psychological forces at play that are potentially more under their control.

For example, although it may seem superficial to appeal to appearance, the sad truth is that first impressions based on looks significantly impact the workings of the justice system. Individuals with baby-faced features receive lighter sentences, and attractive defendants tend to fare better. Quick, appearance-based intuitions seem to prompt legal actors to assimilate later evidence based on their initial impressions. If someone’s appearance is deemed trustworthy, a judge might disregard questionable evidence as a result. In my research involving Hungarian lawyers and law students, two-thirds agreed that court hearings often turn into a sort of credibility contest, where the perceived reliability of opposing witnesses and narratives becomes the deciding factor. Unfortunately, individuals will often be judged by their covers, so the way they present themselves could make a difference.

Narrative anchoring is another crucial factor. People naturally organise information into stories, often without realising that this is just one way of processing information. As a result, information becomes more or less credible based on its ability to fit into a coherent narrative. For instance, a witness may be deemed credible if their testimony aligns with the narrative framework already established in the judge’s and jurors’ minds; otherwise, their weight diminishes. Conversely, even a weaker piece of evidence may be elevated simply because it fits into the story. Therefore, it is essential for each side to present a coherent story of what happened that works in their favour from the outset of the trial. In a murder case, for instance, there might be two competing narratives: one about the defendant’s malevolence, plotting and guilt, and another about the bias of investigators and prosecutors – with each side trying to make its story highly compelling and believable early on, to enhance the resonance of later arguments and evidence.

Loss aversion creates an asymmetry: my concession seems more painful than a similar concession from the other party

In other legal contexts, numerical anchoring is key. Imagine that a judge is deciding on a compensation claim. If they are first presented with a relatively low settlement figure, like $750,000, their judgment will likely anchor around that number. In a hypothetical case, this judge might award $882,000 in damages. However, if they are anchored by a higher proposed figure, like $2,249,000, their judgment might align more closely with this larger number. That’s why parties often try to introduce ridiculously high or low figures during legal negotiations. This might be advantageous in the short term – though it can also prevent the possibility of peaceful settlement, bringing on the high emotional and social costs of court proceedings.

One more pertinent concept is the simple but revolutionary idea, introduced by the psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, that a unit of loss (say, losing $100) hurts more than a unit of gain (gaining $100) feels good. Unfortunately, this loss aversion presents a complication in cases that involve, for example, contract renegotiations, a rearrangement of parental custody rights, or changes in child support. Loss aversion creates an asymmetry: my concession seems more painful than a similar concession from the other party; and the other party tends to value their concession more highly than they value mine.

To address this, people on one side of the dispute often send exaggerated messages that attempt to reframe reference points in the negotiation process, since concessions presented as really painful should be met with commensurate concessions from the other side. But these messages do not always facilitate a successful settlement. In my experience, person-centred psychological principles such as active listening, understanding and convergent communication can help to mediate these cases far better. Empathy creates a unique perceptual field that can dissolve boundaries between people, promoting shared meditative experiences and deactivating heuristic, fast-thinking pathways.

Western thought has long depicted humans as primarily rational beings. However, empirical research has fundamentally challenged this traditional view, demonstrating that humans are not rational decision-makers, but rationalising ones. Decisions are often made through ‘irrational’, fast and unconscious processes, which can be biased. Hence the apparent influence of random numbers, the appearance of witnesses and defendants, the order of evidence, or the framing of information on legal decision-making.

Legal decisions are not totally arbitrary, like a lottery. However, they still fall short of the expected standards. I don’t blame legal practitioners; they simply suffer from the same errors that affect everyone else. Lawyers, however, are more vulnerable in one particular way: they undergo rigorous rational training, which makes them more likely than the average person to develop overconfidence in their thinking abilities. I teach psychology to lawyers, and I see that they are very receptive to the behavioural sciences. But I often feel they see only how others struggle to make rational decisions. This might not be so problematic in everyday life, but for those who create and enforce laws, it could lead to serious errors – ranging from the waste of limited social resources to the wrongful imprisonment of innocent people.

Both law and its application rely on implicit mental models of individual and social behaviour. Today, law is designed for a rational, enlightened view of humans, and works with a sort of legal Homo economicus. This understanding must evolve as behavioural science advances. What’s more, the psychological challenges of the law are a concern not only for lawyers; they should matter to anyone who passes through a courtroom, and especially those who make decisions there. We are all human and, before the laws of the psyche, everyone is equal.