‘It began 12 years ago,’ Madhavi* told me. ‘My face, hands and feet would get contorted; I would get very angry.’ From her purse, she took out tablets of clonazepam and lithium prescribed for anxiety and mood disorders by psychiatrists at one of India’s leading psychiatric facilities. ‘I took these medicines regularly,’ she said. ‘But it made no difference. The psychiatrists helped as much as they could. They even asked about all kinds of things from my childhood. But then they said there was nothing wrong with me.’

This is why Madhavi and her husband Raj, both devout middle-class Hindus, had driven six hours from Delhi to a Sufi shrine called Badaun in India’s northern state of Uttar Pradesh. Through a neighbour, they had learned that the shrine was renowned for the treatment of pagalpan (madness). And it was here, through rituals of Sufi healing, that Madhavi finally began to feel better. At Badaun, her husband said, ‘the thing revealed itself fully, who did it, what it was.’ Over the next few years, the couple from Delhi would become regular visitors to the shrine.

It may be contentious to affirm a Sufi cult of saints as a treatment for mental illness in this day and age. But as I spent time with mareez (patients) like Madhavi, I began to understand why, even in the 21st century, Sufi conceptions of illness and healing have remained helpful for many people suffering from forms of schizophrenia, anxiety, depression and other maladies. What these experiences of Sufi healing reveal are the complexities of a global mental health puzzle that has remained stubbornly unresolved for the past 50 years.

Beginning in the late 1960s, a series of studies by the World Health Organization found that long-term outcomes for severe mental illnesses, including schizophrenia, were better in so-called developing countries that lacked psychiatric support systems. How could this be? In the years since, the ‘outcomes paradox’ (also known as the ‘better prognosis hypothesis’) has been debated but never fully disproved or resolved.

One explanation for the paradox is that the symptoms of severe mental illness are more common in non-Western ‘spirit-infused cultures’ and therefore perceived as less threatening. And without fear, so the argument goes, people who are hearing voices or suffering from other afflictions do not need professional psychiatric help like patients in Western contexts. But as most anthropologists who have worked in so-called spirit-infused cultures will tell you, myself included, hallucinations, disembodied voices and unexplained variations of mood do evoke fear and uncertainty. People like Madhavi often want help.

Caregivers will sometimes ‘take on’ the afflictions of those they are caring for

Another possible explanation is that people in these ‘spirit-infused cultures’ are experiencing forms of mental illness unlike those listed in the diagnostic manuals of mainstream psychiatry. On the surface, this may seem to be true. What afflicted Madhavi and many other treatment-seekers at Badaun is often called an asrat. In Hindi-Urdu, this word translates as ‘effect’, and at Hindu temples similar afflictions are called sankat, meaning ‘crisis’. An asrat is a Sufi concept of illness describing a relational disorder that can spread, like a contagion, between members of a household or between kin. Rather than being located only in an individual body or brain, an asrat is conceived as transferrable between close friends or family members.

The idea of mental contagion may sound unsettling or absurd, but even the most hardened rationalists would accept that relationships and households can have a profound impact on a person’s mental health – research has shown that caregivers will sometimes ‘take on’ the afflictions of those they are caring for. An asrat begins either with a harm done by an intimate other through ‘sorcery’, or more ordinary antagonisms such as a court case or a dispute between spouses, siblings, neighbours, kin or business associates. According to Madhavi, her asrat began because of a property dispute with her brother-in-law’s family. As her husband, Raj, put it: ‘It is always someone from home, never an outsider. The nearer they are, the more dangerous they are.’

The concept of an asrat may appear to be a purely spiritual ‘belief’, entirely irreconcilable with biomedical ideas of psychiatric illness. However, while the maladies of asrat are not described in any edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, even as ‘culture-bound syndromes’, the symptoms are relatively recognisable within biomedical idioms of mental illness. Consider some of the Hindi-Urdu words used to identify its symptoms: pagalpan (madness), shaq (suspicion), vehem (unfounded doubt), chinta (worry), udasi (sadness), tenshun (a Hindi-Urdu version of the English word ‘tension’). So why is it that Madhavi found healing in a Sufi shrine, and not in a psychiatric ward? The answer was more complicated than I expected.

Like many other parts of the ‘developing’ world, psychiatric systems appear to be severely lacking in India. According to 2021 data, there are only around 9,000 psychiatrists for India ’s population of 1.4 billion (and neighbouring Pakistan has fewer than 500 psychiatrists for its population of 230 million). In comparison, consider that the United States, with a population of 330 million, has more than 38,000 registered psychiatrists, and even this is considered a ‘shortage’. What, then, explains the better outcomes experienced by people in places without robust psychiatric systems?

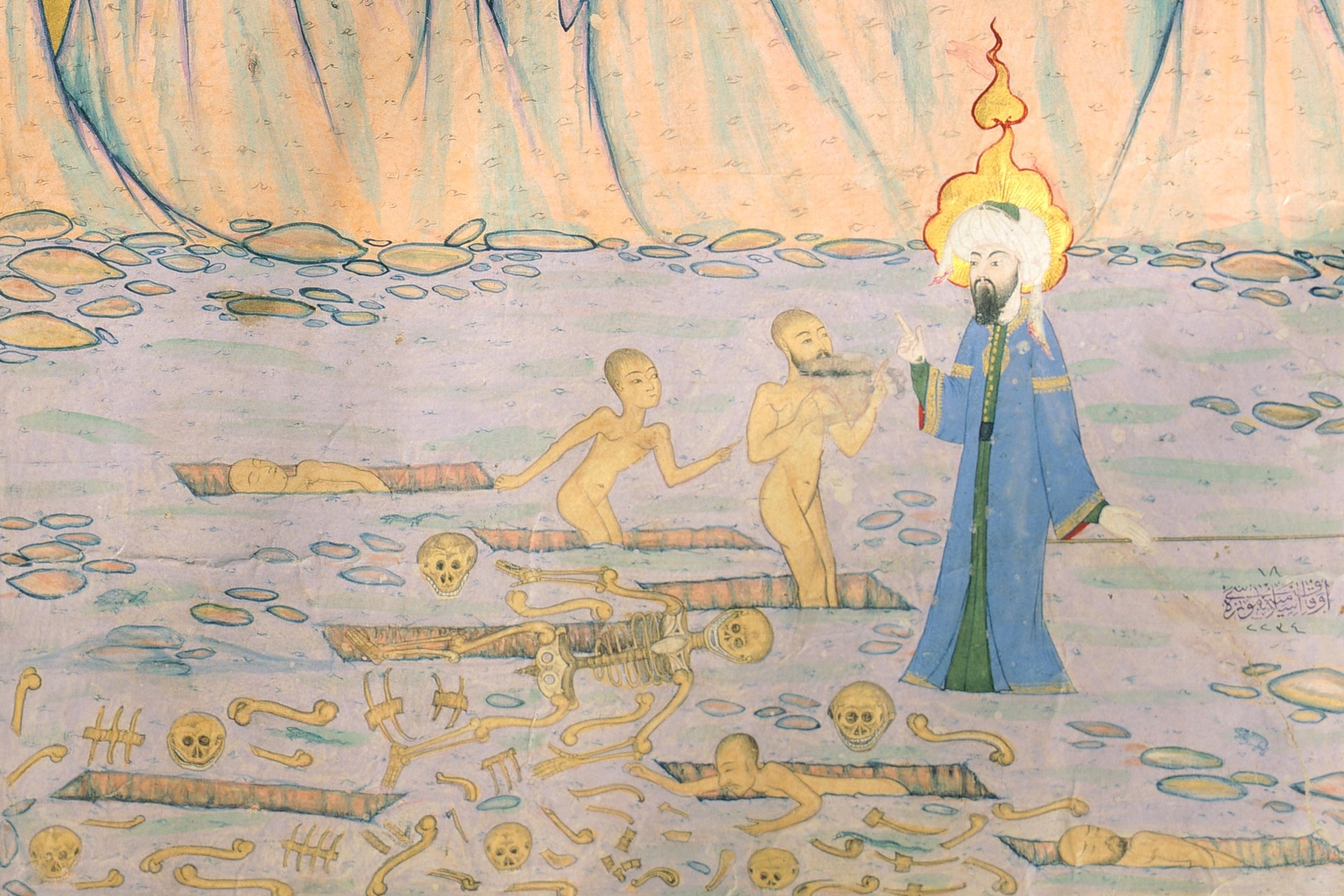

One possible explanation for this apparent paradox, at least in South Asia, may be the continuing significance of Sufi shrine-based healing for mental illnesses. Sufism is sometimes described as a mystical form of Islam, and its shrines are organised around the graves of saints (pirs). Badaun, for instance, is the shrine of two brothers, displaced kings said to have come from Yemen in the 12th century: Sultan Arifin (known as Bade Sarkar) and Badruddin (Chote Sarkar).

Such shrines, when they appear in international media, are often depicted as archaic and barbaric. In contrast, a first-time visitor to a shrine like Badaun may be simultaneously intrigued and disoriented. Unlike India’s often dismal and claustrophobic state-run asylums, Sufi shrines are sprawling, colourful, incense-infused complexes. Most shrines typically have rooms that can be rented by long-term treatment-seekers, and communal spaces for those with no income. They are homes for the homeless. First-time visitors might also find some aspects of the shrine disorienting or troubling. Debates continue about controversial methods used to ‘pacify’ a small minority of violent patients without sedatives or straitjackets, such as chaining them to trees. It may also be disorienting to see patients circumambulating saintly graves by day and, at sunset, ritually self-flagellating while whirling to the hypnotic devotional sounds of qawwali. Among the crowds, patients seeking treatment pay for the services of neighbourhood healers (who are sometimes labelled as charlatans by displeased customers, rivals or shrine-keepers). And whirling patients often express themselves through unsettling screams and wailing. It can all seem hopelessly arcane and superstitious, which make the effectiveness of these spaces even more baffling to outsiders.

I write not as a believer, but as an anthropologist. I arrived at Badaun by a secular route. In 2015, I began an ethnographic project studying mental illness at one of India’s largest public hospitals, the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS) in Delhi. As I followed patients moving between different forms of treatment, I found myself journeying with Hindu and Muslim patients from the hospital to neighbourhood healers and shrines. In India, as in many other parts of the world, receiving medical help does not stop someone from also seeking other forms of healing.

Neighbourhood-based Sufi healers need not be charismatic or have large followings. They can be ordinary men and women, living in poor neighbourhoods or villages. One such healer with whom I have worked closely for the past eight years, popularly known as Sufi-ji, lives in a one-room dwelling in a lower-income neighbourhood in East Delhi. Sufi-ji, who claims to draw his healing powers from Badaun, sometimes meets patients at his home, which is arranged like a miniature version of a Sufi shrine with icons and incense. At other times, he ferries patients back and forth between Delhi and Badaun.

There are more patients visiting Sufi shrines than psychiatrists in India and elsewhere in South Asia

As I followed some of these patients, I was in for a few surprises. The first was the sheer number of shrine visitors, especially at a time when the Hindu Right is on the rise in India. As Sufi-ji put it when I first visited Badaun with him in 2016:

Imagine if all the asylums and psychiatry wards in India were full. How many patients do you think could be accommodated? 30,000 at most? Badaun has more visitors than that on a single day. And then think of how many dargahs [Sufi shrines] there are all over India.

Whether or not these numbers are an exaggeration, there are undeniably more patients visiting Sufi shrines than psychiatrists in India and elsewhere in South Asia. My second surprise was that, without any holy book or theological formula, treatment practices are replicated in both Sufi shrines and Hindu temples across India. Shared treatments include the use of ‘cooling’ water, amulets, sacred ash, daily circumambulations, forms of trance and the ‘expulsion’ of harmful spirits, and also more ordinary social interactions between visiting families and healers.

One further surprise was that psychiatrists were not necessarily against shrine- or temple-based healing. In fact, in 2000, a team of psychiatrists from one of India’s leading institutions for mental health research followed a cohort of treatment-seekers over a three-month period at a temple in Tamil Nadu. The results of their study, published in 2002 in the British Medical Journal, showed significant improvements as measured by psychiatric rating scales.

So how do Sufi shrines like Badaun heal an asrat? A ‘rational’ explanation is that, within the relapsing-remitting tempos of mental illnesses, shrines work as a space of refuge and supportive sociality during the phase when symptoms are, in psychiatric terms, ‘florid’. Once symptoms recede, patients and caregivers return home (or, if they have nowhere else to go, they might find a safe haven in the space of the shrine). This may indeed be the tempo of illness for some people, but it is an explanation that misses out on what is most important about the healing that takes place in Sufi shrines.

Understanding this form of healing requires a clearer conception of what animates an asrat. This form of mental illness often begins with a shaq (a suspicion) about intimate others, which may turn into forms of suspicion and rumination that are not entirely foreign to Western ideas of mental illness. How are these suspicions or anxieties put to rest? According to the philosopher Stanley Cavell, the antidote to self-negating doubt or relational toxicity is not necessarily truth or certainty – finding out what is really going on – but finding forms of resonance with oneself or with others. Cavell calls this attunement.

Restorative ritual actions can be as ordinary as an amulet worn to ‘cool’ an anxious spiral

For those with either serious mental illnesses or more common disorders like depression and anxiety, Badaun and other Sufi shrines offer different forms of attunement. As the psychiatrist Pratap Sharan and I followed patients journeying between hospitals, homes and shrines, we found two forms of attunement that helped us understand the better outcomes paradox: one is subjective, relating to how a person attunes with their own feelings and thought processes; the other is inter-subjective, relating to how close friends and families attune with each other in damaging or healing ways.

Ritual objects such as amulets or incense and repetitive actions such as circumambulations may at times be aiming for similar ends to those of biomedicine and psychiatry, such as containing the tempo of a rumination to prevent it from spiralling into more dangerous or self-negating forms. Restorative ritual actions can be as ordinary as an amulet worn to ‘cool’ an anxious spiral, or an incense said to be charged with keeping voices (‘auditory hallucinations’ in psychiatric terms) at bay. In other cases, the transfer of symptoms between people can serve as a binding force for an injured family unit. These methods are not infallible, and dissatisfied patients may seek out other shrines or psychiatrists for treatment. But for patients such as Madhavi and her husband Raj, the mood-shifting techniques and protection offered by Badaun and its healers allowed them to strengthen their subjective and inter-subjective attunement.

Analysts have often called these forms of spiritual healing ‘folk’ psychotherapy. Last year, the Badaun shrine celebrated its 812th Urs, an annual event commemorating the death of its saints, which suggests that the shrine has been in operation as a healing space for more than 800 years. Viewed from Badaun, we might say that psychotherapy and psychiatry have a relatively emergent and folk understanding of how to treat an asrat.

* Pseudonyms have been used for reasons of security and privacy.

This essay is derived in part from the article ‘The Contagion of Mental Illness: Insights from a Sufi Shrine’ (2022) by Bhrigupati Singh and Pratap Sharan from the journal Transcultural Psychiatry published by Sage.