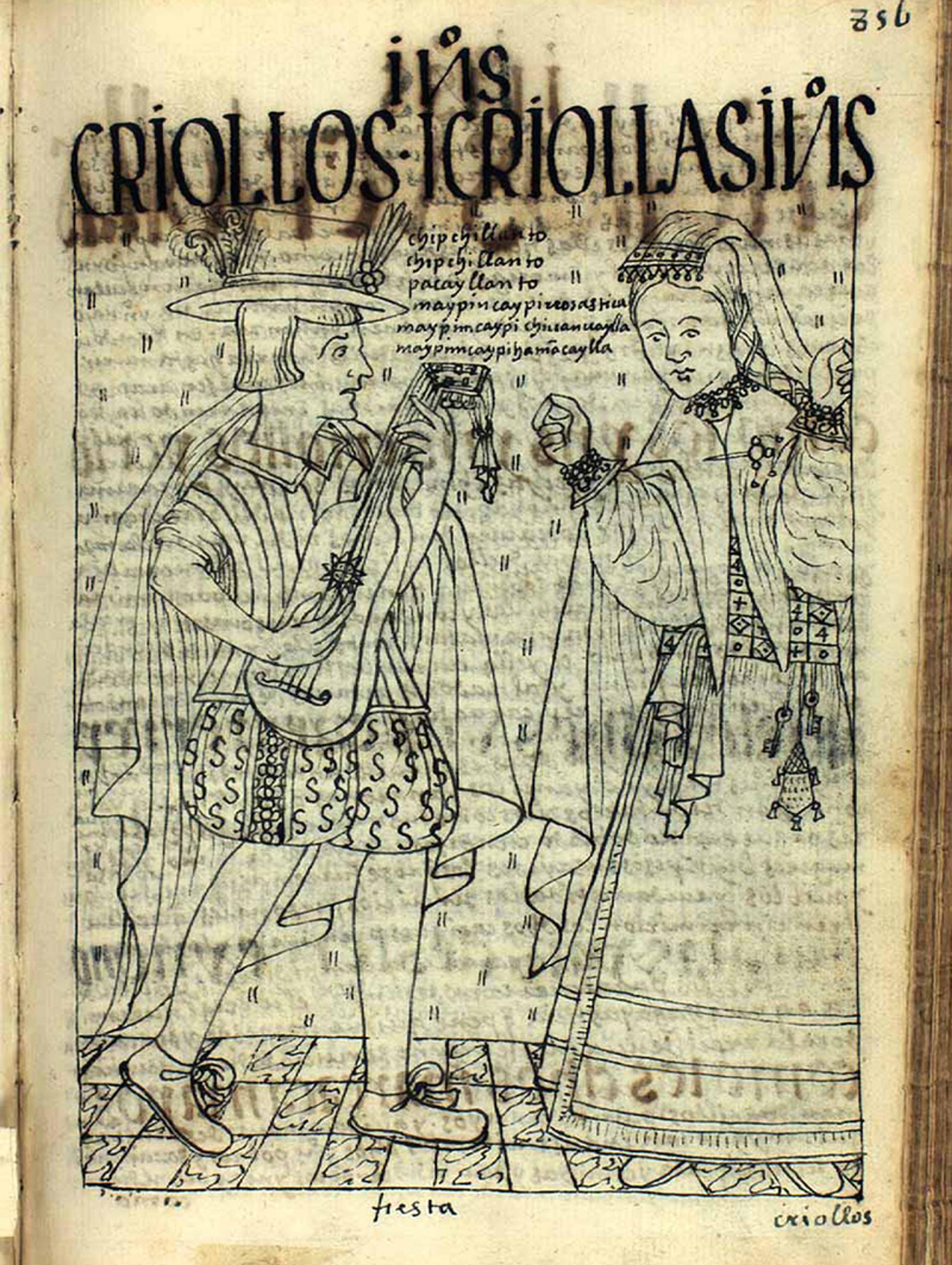

On holidays and other festive occasions, Andean peoples in the Spanish Viceroyalty of Peru liked to dress up. According to 16th-century documents, wealthy Amerindians in Lima, Quito and other colonial cities enjoyed wearing a combination of European and Andean garments, sometimes made of silk and other expensive, imported fabrics (see image below). Their sartorial exuberance annoyed local Spaniards, who issued repeated orders prohibiting Amerindians from wearing such garments. The Indigenous elite did not accept these prohibitions without protest, and launched an appeal in defence of their right to wear velvet and silk. The ban on fine fabrics, they complained, caused them ‘much trouble and vexation’. The case went all the way to Philip II.

Amerindians wearing a combination of European and Andean garments. The man wears a Spanish hat, breeches and shoes with an Indigenous tunic. His companion blends European clothing techniques such as sleeves with Indigenous fashions such as the tupu, or shawl pin, that fastens her tunic. Drawing 321 from El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno (1615-16) by Felipe de Guamán Poma de Ayala. Courtesy Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen

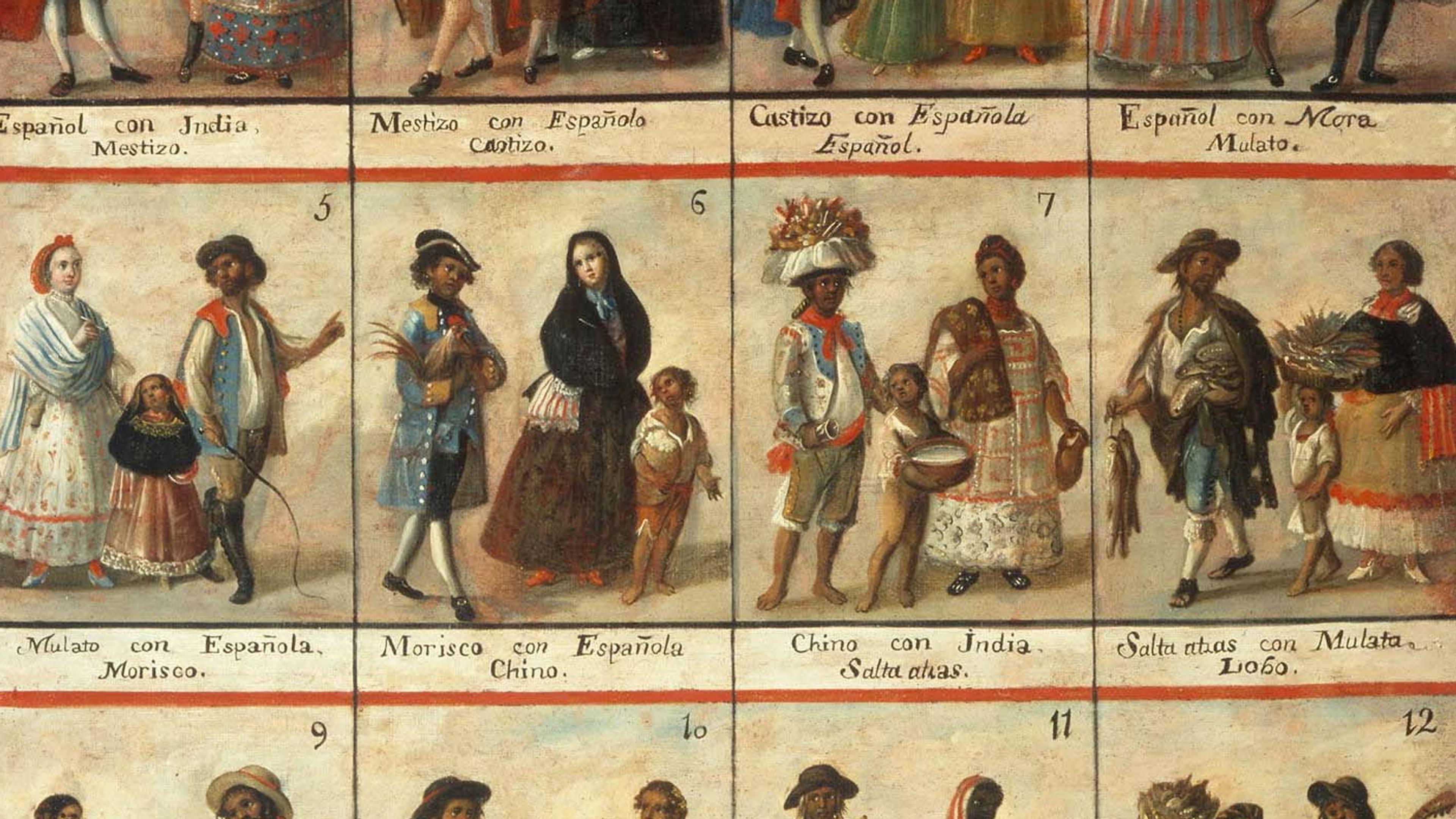

Spain’s American colonies were established in the decades after Christopher Columbus’s inadvertent arrival in the Caribbean in 1492 and endured into the 19th century. From Mexico City to Lima, colonists and locals alike paid close attention to what they and everyone else wore. ‘The lowest class of Spaniards are very ambitious of distinguishing themselves from [people of mixed race], either by the colour or fashion of the clothes,’ observed two Spanish travellers in the 18th century, who went on to detail the ways in which clothing helped differentiate between ‘Spaniards’ and those they called mestizos. Many other observers echoed their comments about the importance of dress in marking out the hierarchies that shaped colonial society.

By their very nature, colonial projects require the construction of sharp distinctions between the governed and the governing. In Spanish America, these distinctions were framed within the language of race, or caste (scholars argue over what term best captures the features of these early modern societies). The territories governed by Spain were home not only to millions of Indigenous people and a much smaller number of Europeans, but also millions of Africans taken against their will to labour in the sugar plantations, mines and other enterprises that for centuries made its American empire a source of profit to the Spanish state. They and their descendants were joined by smaller numbers of merchants, traders and other folk from Asia, Europe and Africa, creating complex and multiethnic societies.

These societies were organised along ethnic lines; innumerable laws regulated whether Spaniards could reside in Indigenous villages (generally not), whether Amerindians were subject to the Inquisition (no), whether men of mixed African and European heritage could attend university (no), and other matters.

At the same time, the colonial state’s racial taxonomies proved inadequate to their intended task. Individuals simply did not stay put in a single caste. One study from late 18th-century Chile found that, over a 12-year period, nearly half the male heads of household in Valparaiso were ascribed different caste statuses in different official documents. Sometimes changes were noted explicitly, as when individuals claimed that their birth had mistakenly been recorded in the wrong register, but sometimes people silently moved (or were moved) from one classification to another. Scholars debate the degree of agency that individuals exercised in these transformations. But it is clear that, as a person made their way through life, it was possible for their ethnicity to change.

Women’s ethnic status was particularly changeable. For example, although marriage records often omitted the bride’s caste altogether, when it was listed, it might be different from that given in her baptismal record. Often the priest who compiled the marriage register chose to accord the bride the same caste as her new husband. In other words, despite their ostensibly genealogical nature, ‘Indian’, or ‘Spaniard’, or any of the other categories into which colonial society was divided, were at root social, reflecting the relationships that shaped the colonial world. In legal disputes, for example, witnesses might be asked whether the defendant was ‘held and reputed’ to be white, not whether they were white. In reply, witnesses might affirm that they considered an individual to be Spanish because they had ‘heard it said’ that they were. Caste was the result of a complex interplay between ancestry, appearance, reputation, lifestyle and social standing, none of which had much meaning when taken in isolation. Clothing mattered too.

The importance of clothing emerges in a court case from 1578 Colombia. When asked to describe a young woman, a witness stated that, because she was always treated respectfully and wore Spanish dress, ‘she did not look like the daughter of an African’. Two centuries later, when a witness in another trial was asked to describe a certain Clara Reina, he responded that ‘from her appearance she didn’t seem to him to be a mulatta and because she wore a particular type of skirt and a little shawl he didn’t think she was white but rather a mestiza’. Clothing could shape how a person was seen, and therefore who they were. Identity was never a fact but rather the outcome of these sorts of social assessments and evaluations by others.

The importance of clothing in creating caste helps explain why people in colonial Spanish America were so attuned to nuances of dress, as the 18th-century Spanish travellers observed. The colonial archive is full of complaints about individuals who changed their clothing or living habits, and thereby ‘became’ a different race. A priest for instance lamented in late 17th-century Mexico City that when an Amerindian put on a cloak, shoes and stockings, and grew his hair, he quickly became a mestizo, ‘and in a few days a Spaniard’. As the anthropologist Joanne Rappaport put it in her book The Disappearing Mestizo (2014), ‘clothing had a “transnaturing power” that did not just reflect identity, but helped constitute it’.

Clothing’s transnaturing power also helps explain why the colonial state consistently issued legislation seeking to regulate the dress worn by different racial groups. European sumptuary laws – legislation stipulating who was allowed to wear particular garments, fabrics or styles of dress, or the occasions on which such items could be worn – often sought to control the cost and type of clothing worn by different classes. Spanish American legislation likewise aimed to constrain ‘common people who without having sufficient wealth wish to dress like the wealthy’.

Spanish American sumptuary laws however were not confined to matters of wealth. Such legislation also stipulated which castes were allowed to wear what. Restrictions on the clothing permitted to specific castes were issued from the 16th century, when people of colour in Lima were for instance banned from wearing silk, jewels and other adornments, and endured to the end of the colonial era. Laws barring non-whites from carrying swords or similar accoutrements were issued repeatedly from the 1530s to the end of the 17th century. Legislation regulating the dress of non-Spanish women was also common. Black and ‘mulatta’ women in 17th-century Mexico were for example prohibited from wearing ‘any gold, silver, or pearl jewellery, nor any Castilian garments, nor silk shawls, nor gold or silver passementerie’.

Some of these laws explicitly reflected the reality that marriage materially altered a woman’s caste. For instance, in 16th-century Mexico, colonial officials barred Black women from wearing gold, pearls, silk or other luxurious goods, unless they were married to a Spaniard – precisely the circumstances that were likely to result in a readjustment of their ‘quality’ to better match that of their husband’s, as noted earlier. They were similarly prohibited from wearing Indigenous garb unless married to an Amerindian man. Most Amerindian women were at the same time banned from adopting Spanish dress. Other legislation contradictorily insisted that sartorial restrictions applied even to women married to Spaniards, in vain attempts to halt the transformative potential of such marriages.

At the same time, dressing as a powerful Spaniard was not the only route employed by those who wished to rise within the colonial hierarchy. Some ‘mestiza’ women for instance chose to adopt Indigenous dress, in ways that proved equally disruptive to the colonial state, which issued repeated ordinances that prohibited women of mixed heritage from dressing as Amerindians unless married to Indigenous men. This mattered because, once dressed in Indigenous garb, these women would more easily become Indigenous themselves, which would entitle them to legal protections such as exemption from paying certain taxes. For a market trader, exemptions from sales tax might offer greater concrete benefits than being considered Spanish.

Settlers in 18th-century Brazil repeatedly asked the Portuguese crown to legislate against the perceived excesses of the clothing worn by non-whites, and the metropolis obliged. In the French colony of Saint Domingue (the future Haiti) sumptuary legislation specifically banned free people of colour from the ‘reprehensible imitation’ of the clothing, jewellery and hairstyles worn by whites. They were instead required to dress in accordance with ‘the simplicity of their condition’. Comparable legislation affecting enslaved people was issued in South Carolina and the Dutch Antilles.

The widespread recourse to such legislation suggests a broader recognition of clothing’s transformative potential, and its ability to transport the wearer across the frontiers of race. Then as now, clothing helped to produce identity, and sumptuary legislation shows us how. To the enduring consternation of legislators and officials, who sought, Canute-like, to control the disruptive potential of a change of clothes, the body and its garments merged smoothly into one.