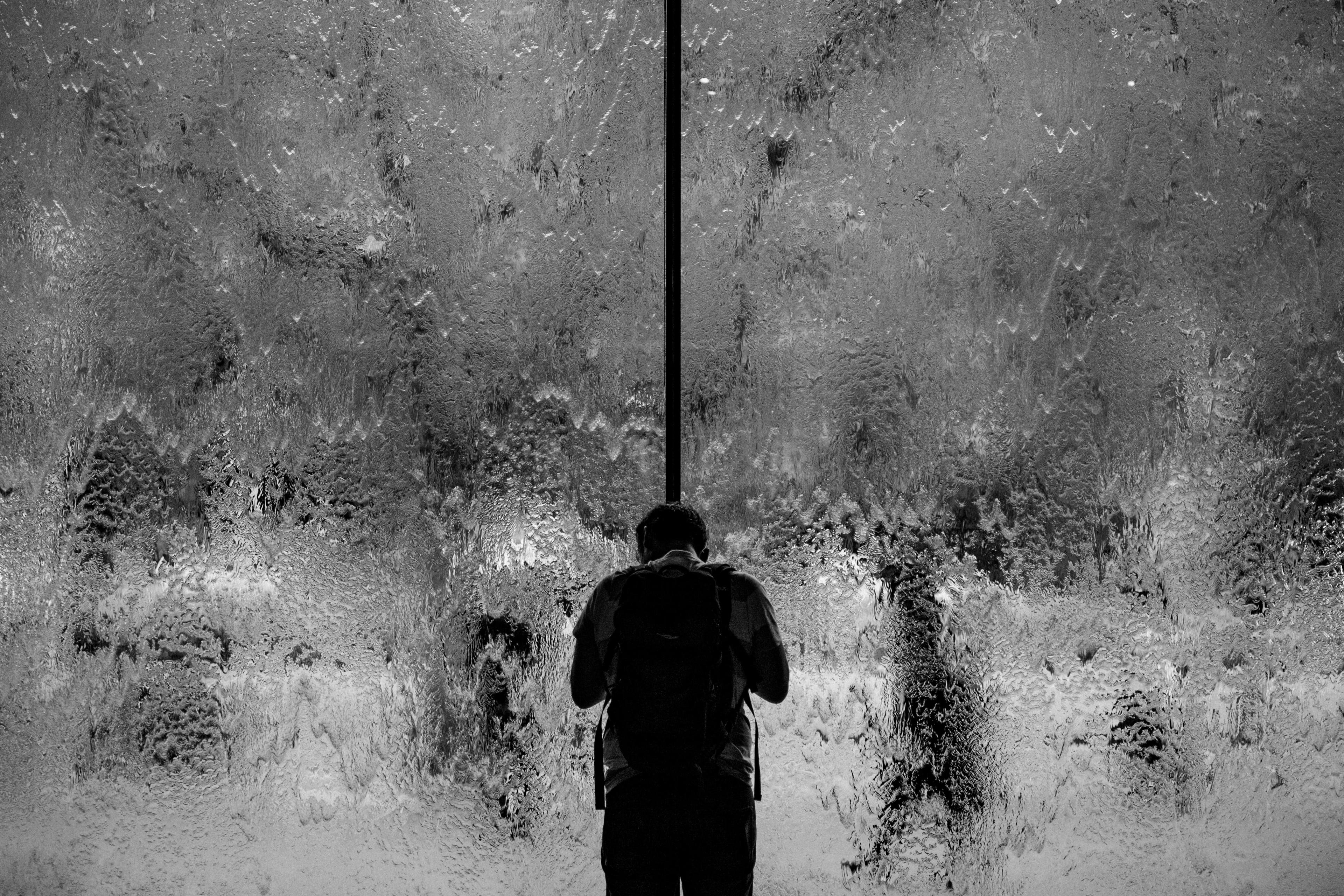

A visit to the doctor’s in a new country always offers a unique glimpse into the finer cultural mores surrounding giving and receiving care. In my native Serbia, the doctor would shake their head in exasperation, averting their gaze to spare me from the shame I should feel for having waited so long to come. When did this fever start? Two whole days ago?! Well, their whole demeanour says, who knows if there is anything we can do now? They will eventually give me one long look full of disappointment and heave a deep sigh to make sure I understand just how inexcusably irresponsible I’ve been, and then they’ll order all sorts of tests just in case. In Serbia, you never needed to look after yourself too much because others would do that for you. The function of worrying, so useful for monitoring our health, was exported into the general culture. You couldn’t push through on your own when everyone, whether you knew them or not, was constantly braced to offer remedies for whatever was or wasn’t ailing you.

From that collectivist culture I moved to one where not relying on my own individual robustness caused dismay. In the Netherlands, when I was unwell, people would wish me strength (not blankets and soup, not care and comfort) and then they would ‘give me my privacy’. Illness and recovery were a personal matter, and the doctor was a representative of his culture, ready to send me away before I even entered the clinic. Whether I clearly needed surgery or had a common bug, every interaction followed the same pattern, reminiscent of a Middle Eastern bazaar. I’d state my symptoms and the doctor would react with surprise as to why I’m telling him all that. What does that have to do with him? What is my question? (There had to be a question.) Then I’d ask for a specific treatment or a diagnostic test, and he would respond as if I’m requesting something extravagant. Instead, he would suggest that we do nothing. The starting positions would thus be set, and the bargaining for care could begin.

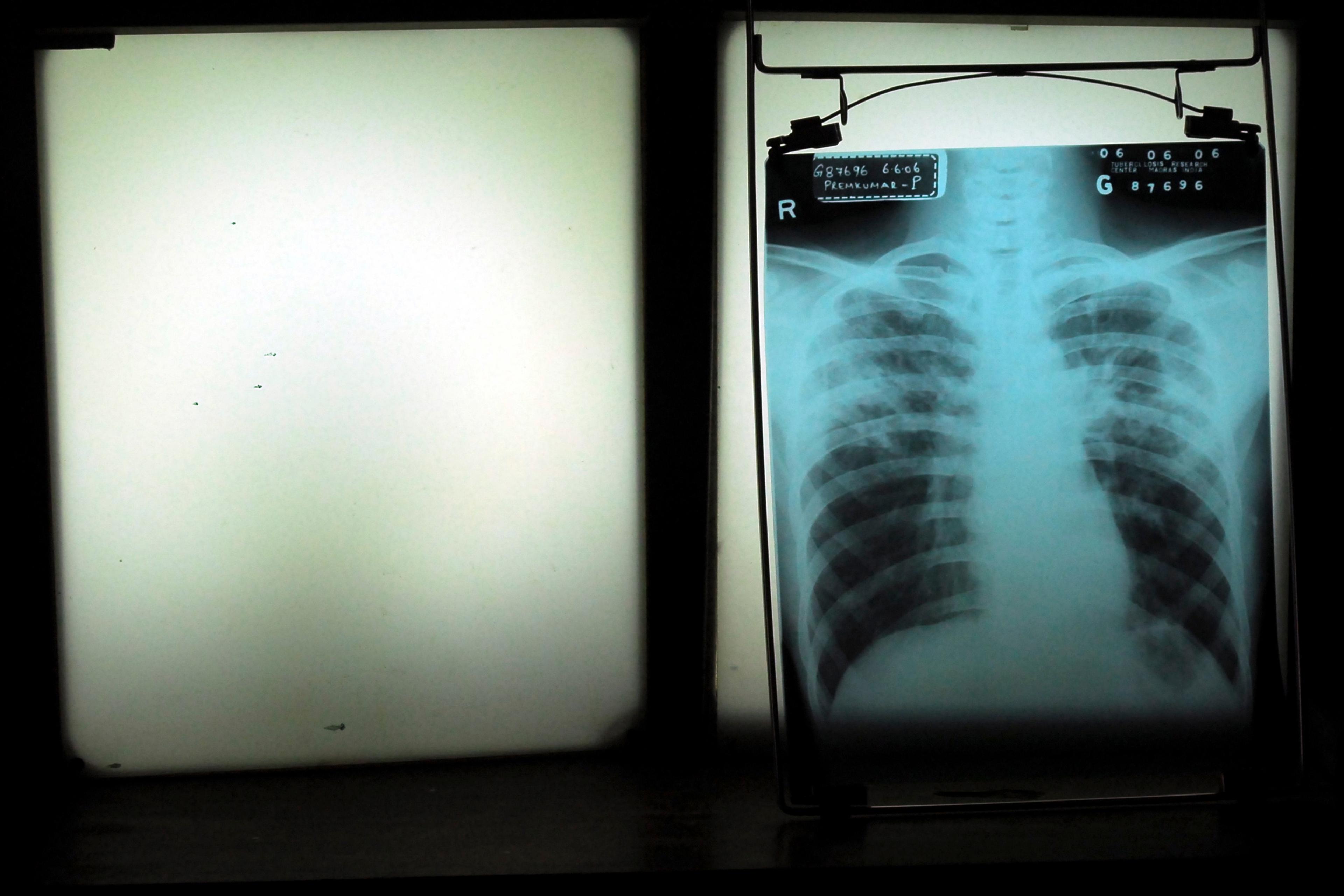

The UK offered a different sort of surprise. I went in with a particularly persistent cough, only to be told by the doctor that she doesn’t recommend cough syrup because all that does is make you feel better. And with that, I was jolted from the gentle familiarity that came from a sense of belonging in this culture where I speak the language and am part of the privileged majority on a wide set of demographics. I was, without a doubt, in foreign territory.

The British doctor was following a gold-standard, evidence-based policy that combines treatment outcomes with costs and availability. My understanding is that studies found that people who take cough syrup report that the illness clears their system more or less in the same amount of time as people who do not take cough syrup. Another way of putting this is that the syrup does not attack the bug that causes the illness, all it does is temporarily ease discomfort, perhaps no better or worse than other remedies. A great deal of precision and skill goes into formulating care pathways based on the best available evidence. My experience, however, underscores that something fundamental can be missed: feeling better is what most of us want from a visit to the doctor.

Empiricism is an enlightened, progressive tradition. Under this framework, only observable facts are considered reliable enough to form part of any research study, and only research studies such as randomised controlled trials provide a reliable-enough backbone for formulating policy. On the face of it, empiricism fits the needs of a healthcare system like a glove. On the flip side, it has to be a self-reflective and philosophically literate empiricism in order to be sound. If we do not consider which elements of life it overlooks, we can slip from a stance of genuine scientific curiosity into one where we apply it prescriptively. From that point on, it can become a box to shut people into rather than a sophisticated approach to helping them.

One example where empiricism can ever so slightly reformulate reality is when a researcher opts for an easily accessible quantity to enhance measurement precision, but that quantity might not be the most important feature of a phenomenon. Say when our body mass index is used as a proxy measure for health risk. A leap from BMI as a statistical correlate to BMI as a semantic representative doesn’t follow from within the confines of narrow empiricism but, in reality, the outcome was that bearing weight began to be perceived as bearing illness. So, does the siloed empiricist bear responsibility for this turn of events? To my mind, that researcher was working with variables but aiming to represent people, whether they pondered this or not.

Psychology is similarly abundant with examples where, in the process of measurement, something is gained – the possibility of controlled experimentation and statistical testing – but some of the essence of an intuitive concept becomes inevitably lost as well. Take the resonance of a metaphor that induces a shared feeling-state in a multitude of readers. Being moved by words is such a powerful way to absorb a message. Boiling this down to ‘How moved does this make you feel, on a scale from one to five?’ just lacks a certain je ne sais quoi. Every time we try to pare down a mental phenomenon to its bare essence, every time we reduce a feature that comes to life in interaction between people, in a complex, constantly flickering network of human contact, to a series of static statements, something of the phenomenon flits away from us. And, yet, we will use short questionnaires to measure traits. We can measure patterns of observable behaviours and intercorrelations of self-report statements – and reliably so.

Sometimes we display a palpable lack of respect for non-empirical thought

But plugging that finding back into a broader question of interest requires infinitely careful consideration of how well we captured the phenomenon we set out to study. That trait should never remain ossified into the questionnaire statements representing it. And yet, another psychologist once told me that they don’t believe in personality – it’s just patterns, they said. There is nothing behind them. In this blinkered version of empiricism, only that which could be directly measured was real, and the rest simply vanished from existence. There was no broader phenomenon to begin with!

This state of affairs is partly a consequence of training academic psychologists exclusively in an empirical tradition. Sometimes we display a palpable lack of respect for non-empirical thought. We’ve been seduced into believing that every other way of thinking is foolish, because we were never encouraged to immerse ourselves in, and learn from, these other ways. For instance, many of my colleagues snort with derision at Sigmund Freud’s Oedipus complex, as though it is a factual statement about a child wanting to sleep with one parent and kill the other. In fact, it is part of a conversation about the psychological damage a child takes if they grow up in a family where they do not play the role of a child. Not quite so absurd, now? Stories can broaden our understanding with more than their bare content. Something vaguely reminds us of something else, something previously elusive clicks into place, and emotional clarity ensues – and, from there, our thoughts can take us in new directions.

Psychology is in dire need of a post-empiricist stance. One where careful and objective fact-collection is relegated back to being a piece in the greater puzzle of exploring who we are, and where other sources of knowledge are valued for bringing something different to the table.

The lessons from psychology might not readily apply to all of medical research, but they resonate in the field of mental health. Complex states of being such as anxiety and depression have become trimmed to a small set of statements on a questionnaire about thoughts related to worry, completely overlooking the more universally familiar, salient sense of persistent existential unease. Even worse, some types of treatment have then become focused on directly decreasing those thoughts or other easily measurable symptoms, while ignoring that these are just a small selection of expressions of the core phenomenon. The researcher and analyst Jonathan Shedler has delved into what we know about this widespread approach to treatment, only to find that research consistently shows that most patients do not get better with it. (They do, of course, ‘improve’ on the questionnaires.) It is easy for a dogmatic empiricist to miss this entirely, and to consider the patients recovered: the universe of possibilities became confined to that which could be straightforwardly turned into variables.

There is a great deal of cultural specificity in what it means to be well

Sometimes, stepping back from narrow empiricism means taking a result and daring to build on it. One of the most consistent findings in research on psychotherapy, for instance, is that the best indicator of whether psychological treatment will be effective is the not the techniques applied or the scientific rigour of the underlying theories but, rather, the relationship between a patient and their therapist. Relationships are vehicles of change. For better or worse, we are most affected by the people closest to us, and when a new person shows a special kind of benevolent curiosity about how we respond to the world, we expand our blueprint of how to comfortably be with ourselves. Perhaps it is time to apply this knowledge more broadly.

If we look beyond the directly accessible variables of experimental research, we can allow ourselves to notice that we also enter into relationships with the social structures relevant to our lives, and that they configure us in subtle ways. My relationship with the cultures in Serbia and the Netherlands played a role in shaping my own concern about myself when I was ill. In Serbia, I’d shrug off symptoms to rebalance the ever-present societal concern about my imminent demise from the sniffles. In the Netherlands, I had to advocate for myself, and to take on the function of worrying completely, because nobody was going to do that for me. I changed.

Similarly, as the anthropologist and psychotherapist James Davies argues in his book Sedated (2021), living in a neoliberal economy can lead us to believe that the end point of psychological recovery is to be functional enough to be productive at work. For me, living in this type of social structure is reminiscent of living with a narcissistic mother who wants only those children who can give her something: we must continuously prove our worthiness; those who fail to satisfy her might be tolerated, but never respected. It is a relationship in which we are not sufficiently recognised beyond our productivity, and so we also stop recognising various aspects of ourselves as valuable. Our ability to be vulnerable, open to leaning on others instead of our personal resourcefulness, to seek comfort instead of merit – they all fade into the background. There is a great deal of cultural specificity in what it means to be well.

Finally, as patients, we enter into a relationship with the medical system, and this relationship can add to our healing or, in some cases, cause us harm. Vulnerable patients especially need the scaffolding offered by regular meetings and partings with a known clinician. They also need living conditions that allow for thriving or, in the absence of that, to be seen by healthcare workers who have been trained to understand the fine-grained influence of social stressors on mental health. Patients need to be helped up by others, by not being processed like a series of disjointed (but easily measurable) symptoms, but rather, as people held in their doctors’ minds with fondness and concern, and with proactive interventions that go beyond offering medication. Relationships do heal, and the workings of the medical system can shift in response to this evidence-based knowledge – but in a world with tunnel vision for unidimensional research variables, I doubt it will.