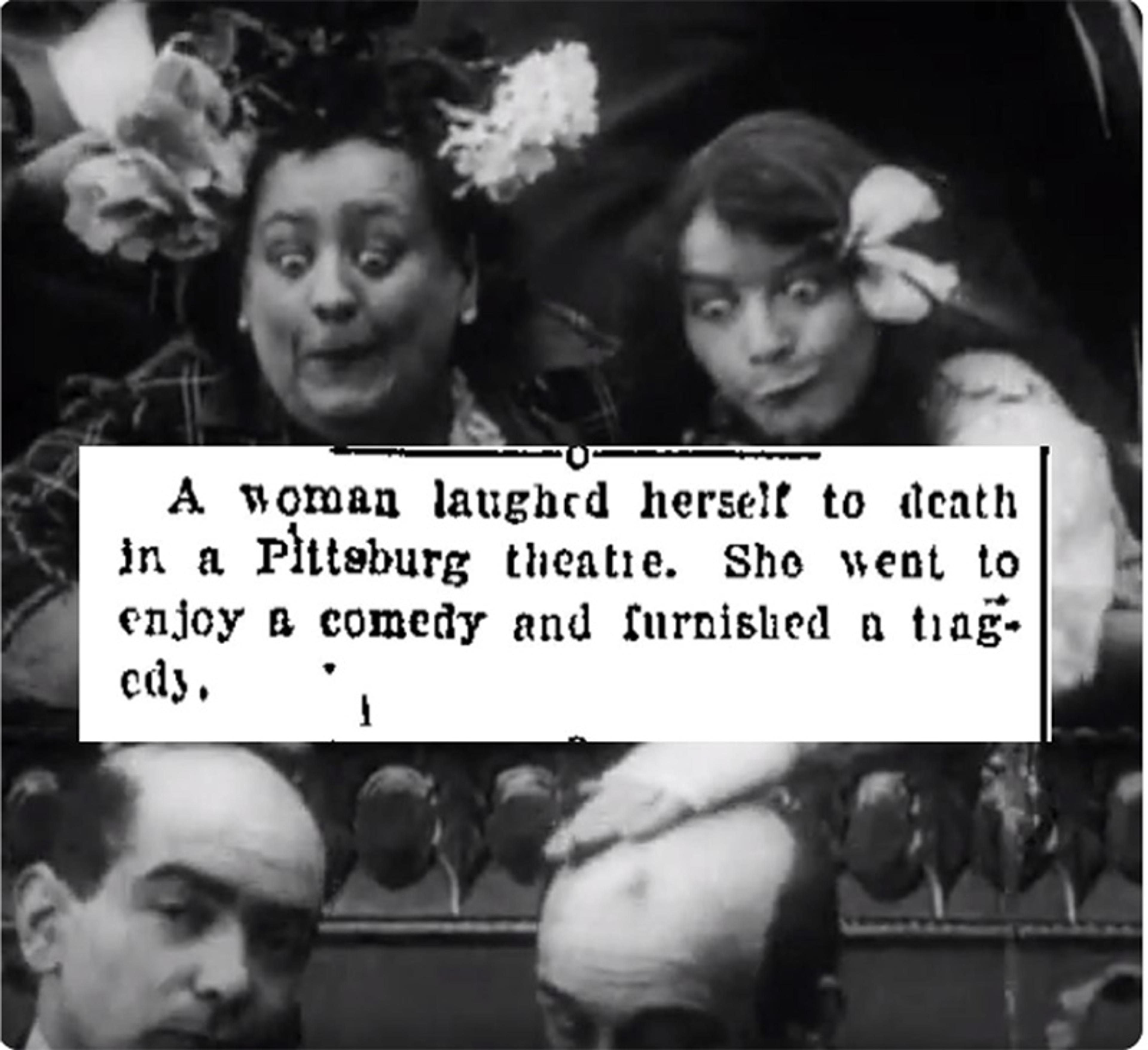

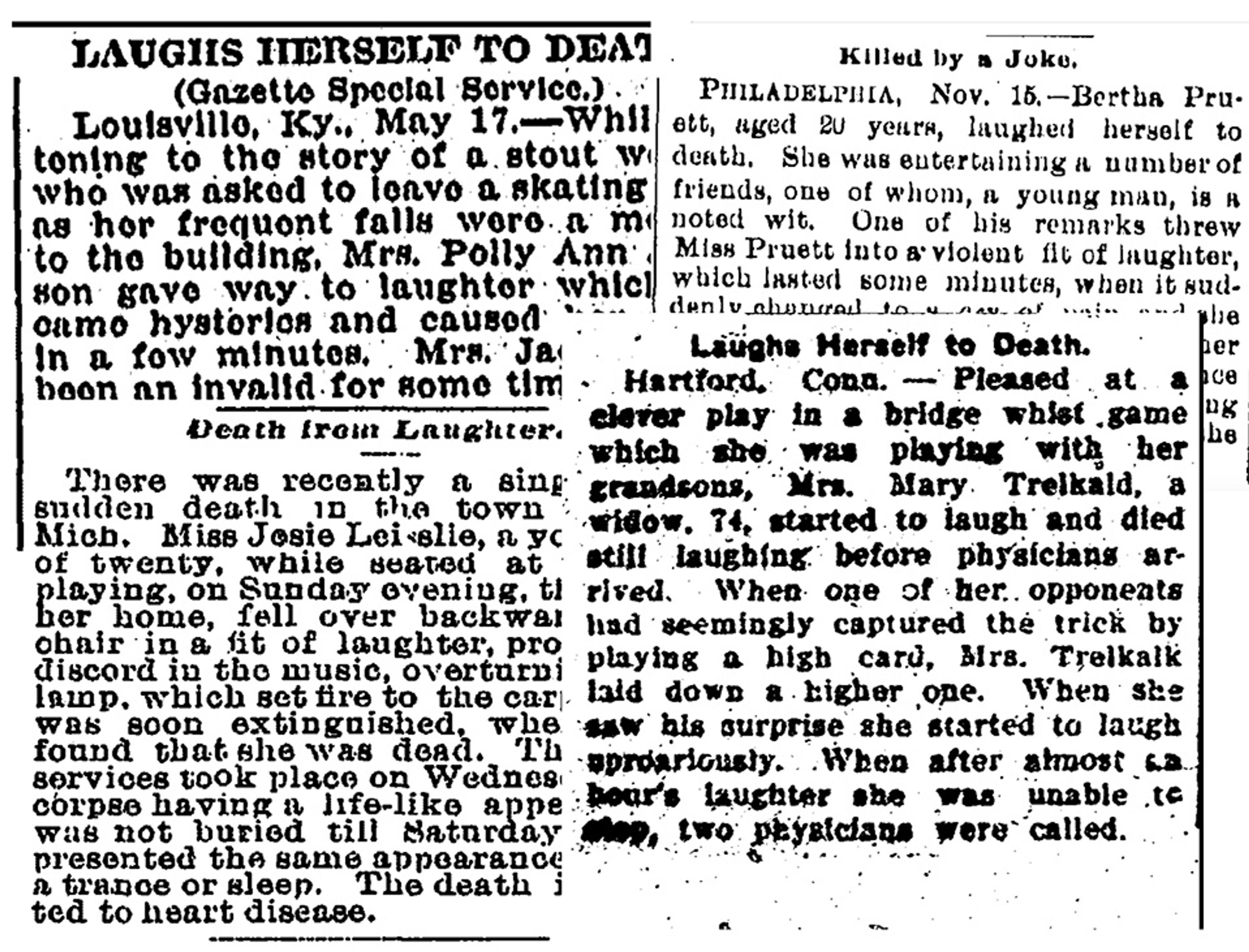

Can you really die from laughing too hard? From 1870 to 1920, hundreds of women in the United States allegedly suffered such a fate. One woman ‘went to enjoy a comedy and furnished a tragedy’ when she laughed herself to death at a vaudeville show in Pittsburgh in 1897. Bertha Pruett was ‘Killed By a Joke’, Mrs Polly Ann Jackson ‘Had Not Laughed So Heartily In Months’, and a woman in Denver ‘may have been about the first to see anything in Colorado to laugh at’ – according to the Dallas Morning News. But were these eye-popping obituaries real? Often voiced in a mocking or glib tone, such as ‘Last Laugh Was Not Best Laugh’ or ‘Score One for the Pessimists’, slews of callous eulogies lampooned their victims for having given up the ghost to such a ludicrous killer.

As I argue in my new book, Death by Laughter: Female Hysteria and Early Cinema (2024), fun-loving women were being terrorised into believing that their unrestrained pleasure could destroy them. At the same time, they were enticed by a ballooning entertainment industry to laugh louder, more convulsively, and with greater corporeal abandon than ever before. ‘Laugh? Why, you’ll have to tie them to the seats so that they won’t roll all over the house in fits of convulsive laughter,’ declared The Moving Picture World in 1912. There were even rumours that local tailors had conspired with travelling vaudeville comedians after too many female spectators busted open their corset staves in spontaneous bursts of uncontrollable laughter. (Imagine trying to laugh while wearing a whalebone corset.)

The explosive popularity of cinema and other such amusements around the turn of the century liberated women. Variety shows, pleasure parks, phonograph parlours, roller rinks, dance halls, wax museums and electricity displays numbered among the many uproarious spaces where women could at last savour their participation in ‘mass culture and a new urban crowd’, as Vanessa Schwartz writes in Spectacular Realities (1999). Often compared to a crazy dream or collective hallucination, cinema epitomised the potentials of popular new spectacles to transform the material conditions of ordinary experience for disenfranchised and minoritised audiences.

From Nursemaids Strike (1907). Public Domain

From Nervous Kitchen Maid (1907). Public Domain

By the beginning of the 20th century, women were becoming political players. They lobbied for the vote, took up space in public, walked off the job, protested for higher pay and better labour conditions, and migrated across the world to seek out new lives in melting-pot urban metropolises. Politically active women were irresistible subjects of representation for the new medium of cinema. In early feminist films such as The Dairymaid’s Revenge (1899), The Nursemaids’ Strike (1907) and The Suffragette’s Dream (1909), women break all the dishes in the kitchen, wave protest signs that say: ‘Down With The Bosses’, electrocute police officers, and weaponise freshly squeezed cow’s milk to humiliate their sexual assaulters. It is worth emphasising that most of these movies were slapstick comedies. In cinema (if not in real life), women got to have the last laugh in retaliation against their male tormentors and capitalist oppressors.

So it’s no wonder that the old guard started peddling morbid rumours of women’s pandemic mortality by hysterical laughter. As Margaret Atwood put it, men are afraid that women will laugh at them; women are afraid that men will kill them. Etiquette columnists even scolded ‘smart ladies’ not to show their teeth, convulse their diaphragms or make any noise at all while cachinnating. (This technique was known as ‘the new laugh’.) Meanwhile, vaudeville houses and nickelodeon storefronts lured in thrill-hungry patrons by blaring ‘laughing song’ phonograph records from outside the theatres. In the wise words of the notorious ‘Laughing Girl’ Sallie Strembler: ‘HAHAHAHA-HEHEHEHEH-HOHOHOHO!!!!’ Loosely paraphrased: Abandon restraint all ye who enjoy themselves here.

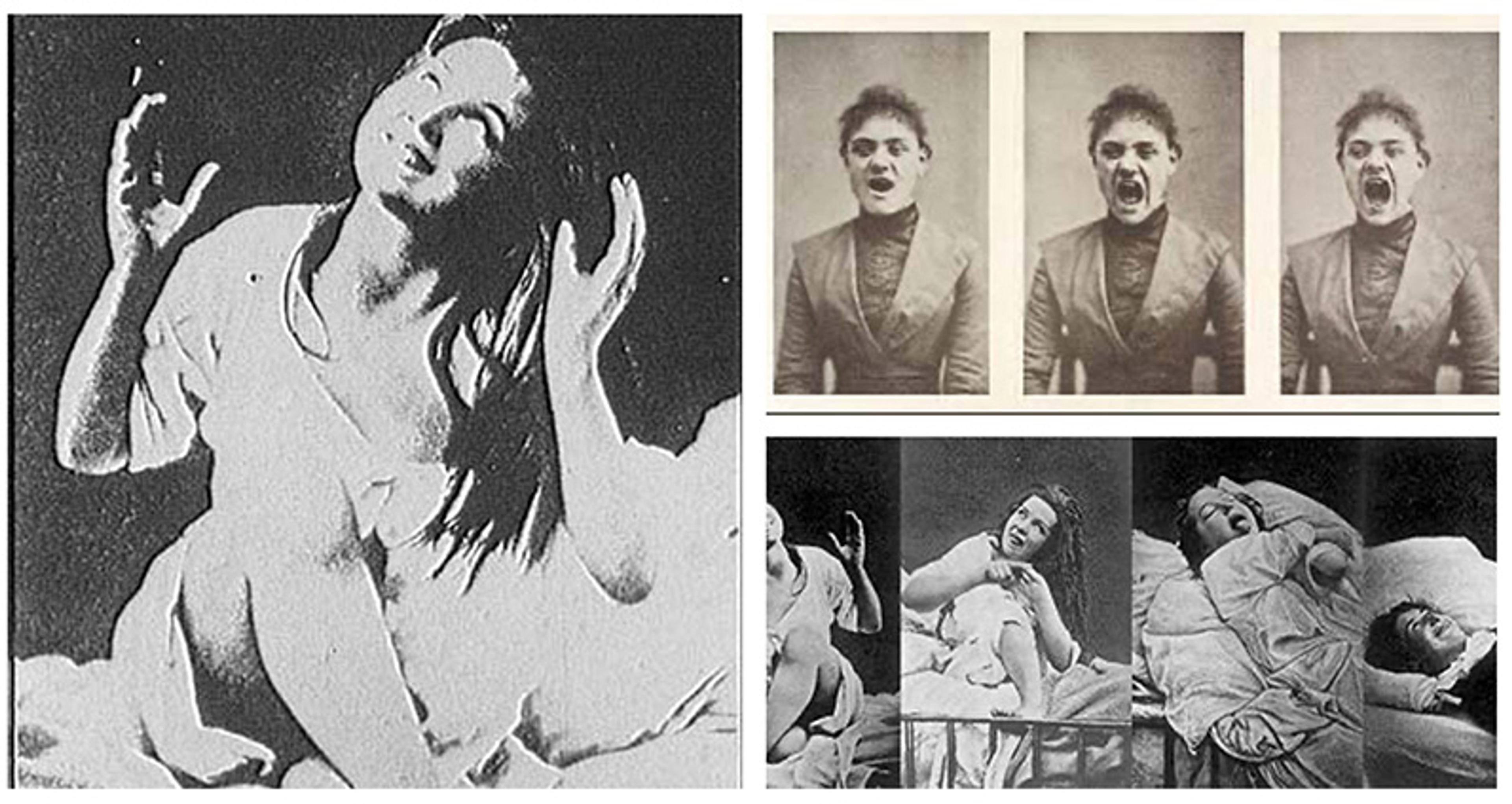

The backdrop to the widespread panic about these unleashed and uninhibited women was the 19th century’s raging obsession: female medical hysteria. The public was morbidly fascinated by the spectacle of women afflicted by mysterious physical ailments with seemingly no organic basis in the body. From the Greek word hystera (meaning ‘uterus’), by 1883 the diagnosis encompassed nearly 20 per cent of all cases at the Paris Salpêtrière Hospital – 20 times its 1 per cent rate in 1845, according to the feminist historian Elaine Showalter’s The Female Malady (1987). The French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot photographed his most famous hysterics and hypnotised them on stage in front of 400 weekly spectators.

Charcot’s star patient Marie ‘Blanche’ Wittman was known as the ‘Queen of the Hysterics’. Women like Wittman would assume impossible acrobatic positions (described as ‘clownism’: Charcot was also a big fan of the circus) while suffering epileptic convulsions and erotic hallucinations. It was quite a scene. The amphitheatre overflowed with ‘a multicoloured audience drawn from tout Paris’, recounted the psychiatrist Axel Munthe in his 1929 autobiography, ‘authors, journalists, leading actors and actresses, fashionable demi-mondaines, all full of morbid curiosity to witness the startling phenomena of hypnotism almost forgotten since the days of Mesmer and Braid.’ Even the French stage actress Sarah Bernhardt visited Charcot’s psychiatric theatre to observe a staging of grande hystérie in preparation for her demanding role in Adrienne Lecouvreur.

Sarah Bernhardt in Adrienne Lecouvreur. Courtesy the NYPL

Jean-Martin Charcot with a patient under hypnosis at the Salpêtrière hospital, Paris, in 1888. Wellcome Collection

What is hysteria? Now a long-debunked diagnostic category, the mysterious ailment ran roughshod over 19th-century psychiatric medicine. Symptoms of the disease ranged from ordinary exhaustion, boredom, fatigue and nervousness to epileptic orgasms, uncontrollable hiccupping, clownish acrobatics and transspecies metamorphosis. Its origins defied scientific understanding – arising from nowhere and then vanishing without a trace – and its symptoms assumed such a perplexing range of extremes that it was often disparaged as a mere wastebasket for any inexplicable affliction.

Patients suffering from supposed hysteria at the Salpêtrière hospital, Paris, in the mid-19th century. Courtesy the Wellcome Collection

Yet nowhere in all the psychiatric case histories was laughter considered at length as a symptom, despite the laughing madwoman’s persistence as a popular trope of sensation literature, gothic theatre and phantasmagoric visual culture. In Pierre Janet’s comprehensive overview The Major Symptoms of Hysteria (1907), there is only one mention of hysteric laughter (as an involuntary reaction to sedation for an illicit abortion), which is briefly sandwiched between incidents of serial hiccupping and medieval epidemics of meowing, whinnying and barking. Incredibly, hysteria was not retired from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders until the late 1970s.

When we think of laughter as ‘hysterical’, we often associate that idiom with ordinary pleasure and contagious enjoyment. But until the very end of the 19th century, the notion of ‘laughing hysterically’ was the last thing you would ever want to experience with your body. Prior to that time, to laugh hysterically meant to suffer extravagantly from unresolvable mixed feelings, such as despair and ambition, disgust and arousal, or hopelessness and determination. ‘Hysterical laughter’ primarily afflicted nervous or emotional women whose morbid ambivalence paved the way to their uncontrollable, mirthless convulsions.

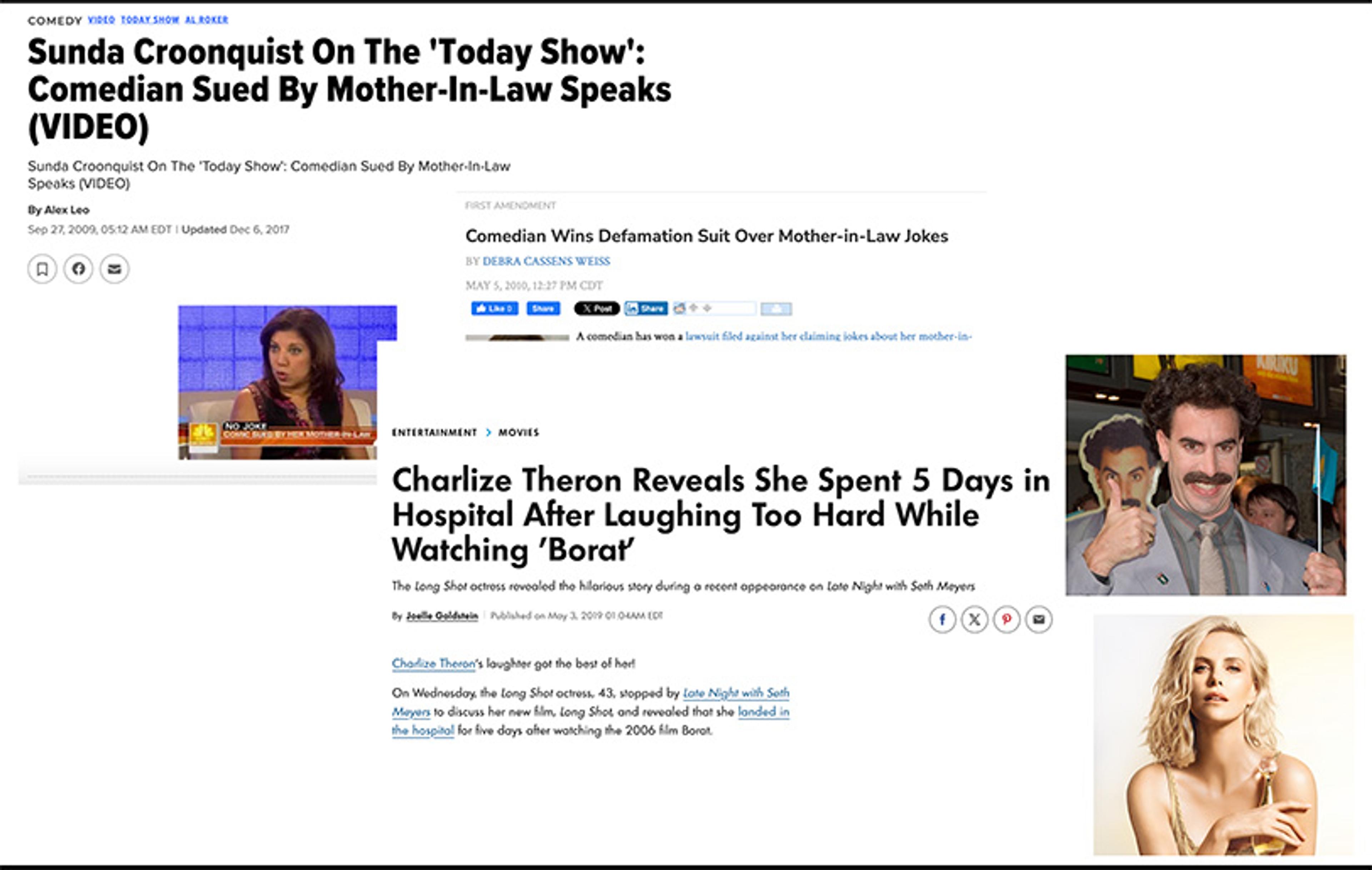

Sunda Croonquist’s outraged in-laws sued her for ‘making too many mother-in-law jokes’ in her standup act

But with the onset of raucous modernity – laughing songs, vaudeville extravaganzas, pleasure parks, and crazy moving pictures – the gendered pathos of emotional hysteria fuelled the insatiable contagions of wild mass culture. Sensations of joyous laughter and unruly madness collided in the raucous bodies of pleasure-seeking women around the coming of the 20th century. The explosion of women into the public sphere and political life via mass culture made hysterical laughter fun – as long as it didn’t kill you. Film exhibitors even offered daredevil spectators life insurance for ‘death by laughter’ at ‘dangerously funny’ slapstick comedies.

Legal hazards engulf the comedy industry today, but the target has shifted from laughing spectator to edgy practitioner. Comedians face litigious backlash for everything from plagiarism to insult humour to mother-in-law jokes, exemplified by the ‘mother-in-lawsuit’ against Sunda Croonquist whose outraged in-laws sued her in 2009 for ‘making too many mother-in-law jokes’ in her standup act. In contrast, Charlize Theron absolved Sacha Baron Cohen after she ‘was hospitalised for five days’ from ‘laughing too hard while watching Borat.’ (She had a herniated disc but Borat was the final straw.)

Today, we fear nothing more than wrong or injurious laughter. Culture wars are staked on the slippery line between outrage and excitement. But the point of jokes is to give us access to the taboo – temporarily liberating what would otherwise have to remain unsaid and unthought. Wild laughter stirs up unrealised collective desires. It flirts with dangerous impulses, risky attachments and inconvenient thoughts, unleashing an extremity of feeling that spreads through your whole body and sparks new sensations of community and solidarity. Whether a cynical rumour or utopian fantasy, the possibility of death by laughter may be just too beautiful for this reality.