Just as nearly everyone experiences physical health problems such as infections or injuries, most people will experience one or more mental health problems over the course of their lives. At present, only a fraction of individuals who have these problems come to the attention of a clinician.

Many live with unexplained suffering for years, feeling isolated and burdened by an invisible weight that is hard to articulate. Identifying and naming these experiences of suffering is an important step toward understanding and treatment. A diagnosis given by a trained mental health professional, such as a psychiatrist or clinical psychologist, can provide relief by offering professional recognition of someone’s distress and disability. It can guide a person towards appropriate interventions and support. And it can come with a comforting realisation that one’s problems are also experienced by others, and that they have been carefully studied by clinicians and researchers.

However, it’s important for people who receive a psychiatric diagnosis for a mental health problem, or who learn about someone else’s diagnosis, to have clarity on what getting a diagnosis means – and what it doesn’t mean. Some people expect a diagnosis to describe their problems perfectly. Others are tempted to dismiss a diagnosis as nothing more than a label. Some misunderstand a mental health diagnosis as the identification of an abnormality or disease in the brain. There is also considerable stigma around mental health diagnoses, and misunderstandings about their nature and outcomes are widespread. When they are seen as pejorative labels, or the person with a mental health problem is viewed as having a damaged self or an incurable brain disease, diagnoses can induce shame and pessimism.

Diagnoses in mental healthcare are far from perfect and can cause harm if misapplied, but they also carry more depth and significance than just applying a label. I’d like to share a few different and general ways of understanding these diagnoses – focusing on some key yet underappreciated points – to paint a more realistic picture of their meaning and use.

A diagnosis is a description

Most psychiatric diagnoses are descriptive in nature: they refer to observable and reportable patterns of experiences and behaviours that cause distress or impairment in a person’s life. For example, a diagnosis of generalised anxiety disorder is made when someone experiences excessive, uncontrollable anxiety and worry along with a certain number of other symptoms – such as restlessness, difficulties with concentration, muscle tension, sleep disturbance, and so on – for a specific period of time. At present, the diagnosis is not based on medical tests (other than to exclude relevant medical causes, such as hormonal disorders), nor does it pinpoint an underlying biological or psychological cause.

This descriptive approach reflects the current state of scientific knowledge in psychiatry and psychology. It’s a pragmatic way to group and treat presentations with similar symptoms, even though the relevant causes are not fully understood and are likely different in different people. (After making a diagnosis, a competent clinician will then go beyond descriptive features to further explore the patient’s personal experience and hypothesise about causes and contributing factors; this is called a clinical formulation. Mental health problems arise from the interaction of various factors – such as personality characteristics, genetic vulnerabilities, childhood development, social adversity, and patterns of brain circuitry – and the crisscrossing web of causes doesn’t respect the boundaries of clinical description.)

Psychiatric diagnoses offer a limited form of explanation, namely that of pattern recognition and matching

To diagnose patients, mental health professionals rely to varying degrees on the descriptions contained in official diagnostic manuals, including the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Here you can find categories such as obsessive-compulsive disorder, social anxiety disorder and anorexia nervosa, along with characteristic symptoms of each. Despite their widespread use, these manuals are imperfect tools. A proper diagnosis is based on more than a list of symptoms; it is the outcome of a thorough evaluation that takes various possibilities into account. Clinicians also frequently use names and labels (such as treatment-resistant schizophrenia) that are not in the manuals but are recognised and accepted by professionals in the field. When a diagnosis is uncertain or unclear, which happens quite often, clinicians rely on narrower clinical features, such as delusions, obsessions or mood instability, instead of a specific category to guide treatment.

It is often said that psychiatric diagnoses don’t explain anything, though this is not quite true. They do offer a limited form of explanation, namely that of pattern recognition and matching. When a diagnosis is made, the clinician is conveying to the patient that their presentation matches this well-recognised pattern of symptoms, and not these other patterns that could conceivably apply. Based on that, we can link the person’s presentation with existing medical knowledge and use treatments that have been studied for that pattern. This is why accurate diagnoses of conditions such as autism and ADHD can offer powerful explanations for patients and lead them to look at their lives in a new light, even though the causes and mechanisms remain unknown.

A diagnosis is a prototype

In the official diagnostic manuals, categories such as bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or generalised anxiety disorder come with stringent criteria for applying the diagnosis. The view taken by clinicians is usually not so rigid. Instead, these categories are often understood as prototypical: they are based on the typical or illustrative example of a mental health problem from which real-world presentations will often deviate. From this perspective, a diagnosis is a ‘best fit’ match between someone’s experiences and a prototype, which represents the most specific or notable features of a condition. Some cases will fit a category better than others, just as a robin is a more typical example of a bird than an ostrich is.

The boundaries between different mental health conditions can be fuzzy

This prototype view allows for flexibility, acknowledging that mental health conditions don’t present in a uniform way. For example, two people can share a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, with prolonged and persistent low mood, but they can have very different accompanying symptoms. One might struggle with fatigue, sluggish thoughts and movements, and early morning awakening, while another might experience restlessness, difficulty falling asleep, and increased appetite. Appreciating this variability can reduce the frustration that comes from feeling like one doesn’t ‘fit’ the typical mould of a diagnosis. It can also help people advocate for care that meets their unique needs, which sometimes means trying different therapies, medications or lifestyle changes before finding the combination that works for them.

Thinking of a diagnosis as a prototype also recognises that the boundaries between different mental health conditions can be fuzzy. Indeed, around half of people will meet the criteria for two or more concurrent disorders, and nearly 90 per cent of people with one disorder will qualify for another over several decades. Having more than one diagnosis doesn’t necessarily mean that someone has multiple, unrelated disorders with independent origins; it simply means that the symptoms they’re experiencing fit more than one prototype. For instance, a person who has experienced trauma may meet the criteria for both PTSD and depression, reflecting the presence of interconnected sets of symptoms stemming from related causes rather than two separate disorders.

A diagnosis is imperfect and subject to change

Psychiatric diagnoses are based on the best available understanding of someone’s mental health condition at the time. However, this kind of assessment is often more fallible than in many other areas of healthcare, where objective tests and laboratory markers facilitate the process. Mental health diagnoses are subject to biases, limitations in current knowledge, and variability in how symptoms manifest in different individuals. They depend on how a clinician interprets the symptoms and how the patient reports them. Different clinicians might arrive at different diagnoses based on the same set of symptoms, even if they agree on what symptoms are present and whether they require treatment.

A diagnosis used today might be revised in the future

In some cases, a diagnosis that was appropriate for someone at one point in time may no longer be the best fit if previously unknown information is revealed, new symptoms emerge, or the pattern of symptoms changes. A personality disorder might be re-diagnosed as PTSD if a previously unreported history of trauma comes to light and the person’s symptoms are better understood as lasting responses to recurrent trauma. Depression might later be re-diagnosed as bipolar disorder if someone has a manic episode.

Additionally, new research and a better understanding of mental health conditions can lead to changes in how they are defined and diagnosed. A diagnosis used today might be revised in the future. What was once diagnosed as a separate disorder might later be understood as part of a spectrum with another disorder – as in the case of Asperger syndrome, which was subsumed under autism spectrum disorder in the fifth edition of the DSM. What is currently diagnosed using distinct categories might be diagnosed differently in the future: the ICD has already shifted from using separate categories of personality disorders, such as narcissistic personality disorder or antisocial personality disorder, to a model that is more focused on describing someone’s specific personality traits (such as negative affectivity and disinhibition).

Diagnosis is a partial perspective on a person’s challenges

There are many ways to describe, understand and treat mental health problems. If we focus only on one or two viewpoints, we’ll miss out on a fuller understanding. There are hundreds of psychotherapeutic approaches in psychiatry and psychology, each with its own set of assumptions about the nature of the problem at hand. But perspectives outside of medicine and psychology are also valuable. Major depression is a medical disorder, but it can also represent a state of existential and spiritual crisis, necessitating a deep re-evaluation of one’s life goals and values. Generalised anxiety is a psychological problem, but it can also be a response deeply linked to a socioeconomic precariousness that demands political solutions. Therapeutic communities such as 12-step programmes for addictions demonstrate the value of understanding behavioural problems through lenses other than that of medicine. Therefore, it is important to remember that a psychiatric diagnosis does not, by itself, invalidate other cultural and spiritual ways of approaching a problem, and these perspectives remain essential tools of recovery for a lot of people.

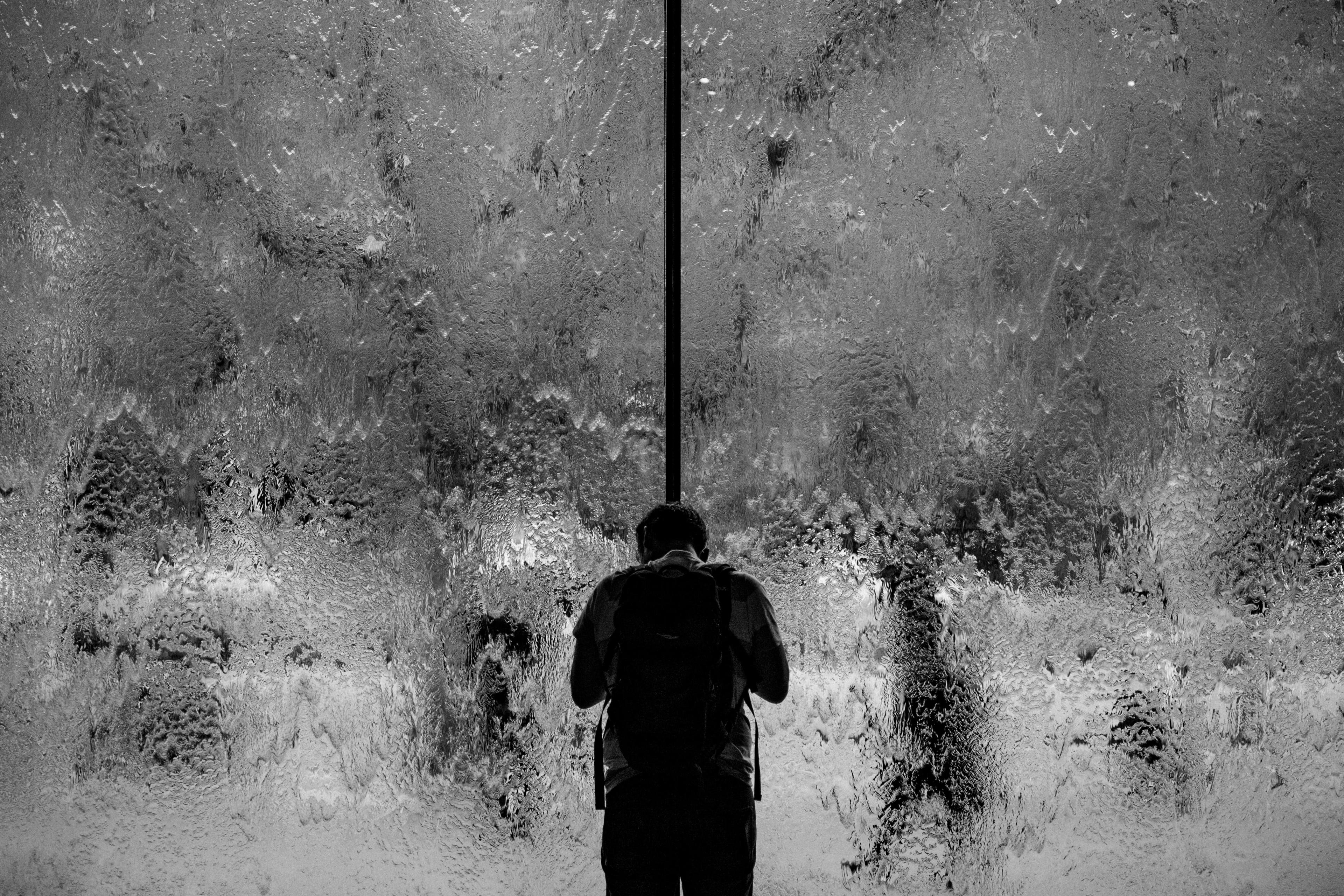

A diagnosis does not describe the essence of a person

A psychiatric diagnosis can profoundly shape how a person sees themselves. After receiving a diagnosis, they might begin to view themselves primarily through the lens of that category, reducing their complex, multifaceted self – with all the nuances of their personality, background and experiences – to a single aspect. This over-identification with a diagnosis can be further complicated by internalised stigma that makes people feel fundamentally flawed or inadequate, eroding their sense of self-worth.

A diagnosis can also foster a mistaken belief that one’s condition is unchangeable. People sometimes feel trapped by their diagnosis (especially for diagnoses that evoke a sense of pessimism, such as schizophrenia or personality disorders), and they may be unable to envision a future where they feel differently or their symptoms improve. Someone who over-identifies with a diagnosis might also begin to behave in ways that align with the expectations attached to that diagnosis, even if those behaviours were not originally prominent. For example, someone diagnosed with an anxiety disorder might start avoiding situations that wouldn’t actually be anxiety-provoking for them, believing that their condition makes them predisposed to overwhelming anxiety in any uncertain or challenging scenario.

The key to mitigating all of these risks lies in being mindful that a diagnosis is just one piece of a much more detailed puzzle of personhood. Seeing diagnosis as a useful but fallible tool for addressing mental health problems can help the diagnosed person and those who know them keep their complex individuality in sight, including their strengths, interests, ambitions, relationships and all the other elements that make up an identity.

Mental health problems are not immutable by default. People can recover and symptoms can go into remission. Even in the absence of remission, people can experience substantial improvements in their functioning over time and achieve fulfilling, successful lives. It is true that some people live with chronic mental health challenges, just as some people live with chronic physical health challenges. But these chronic problems, even when they deeply influence how someone relates to themselves and others, are still only one part of a more complicated identity. The possibility of growth and transformation is almost always there.