I see. When I open my eyes, I see a long stretch of grass, terminating in an unoccupied café, with chairs and tables stacked neatly by the door. In the distance, I see a large hospital blurring into the horizon. My visual consciousness represents a rich collection of objects, shapes, and colours. This all happens with ease: I just open my eyes and there it all is, apparently instantaneously.

This is all so effortless, that it’s easy to think of seeing as a straightforward process. Of course, that’s not true. In reality, the conscious view I have of the world is the end result of an immense level of computation. My eyes register information about light, and that information is processed in several different systems located throughout my brain, before showing up in my visual consciousness. The impression I get of the outside world (the grass, the café, the hospital) is a very distant descendent of the information that first entered my eyes. Of course, we’re not privy to all of this processing. Almost all of the work goes on entirely unconsciously, inaccessible to our own conscious minds.

One challenge for psychologists, philosophers and neuroscientists is to find ways of unpicking how this unconscious processing works. Illusions represent a valuable way to do this. Visual illusions are cases where the visual system has made a mistake, and as a result we see the world not as it really is. These mistakes provide us with tantalising glimpses into the secret workings of the visual system. They force us to think: what must the brain be like, in order to get that particular thing wrong? What processing is going on, which results in that error, rather than any other?

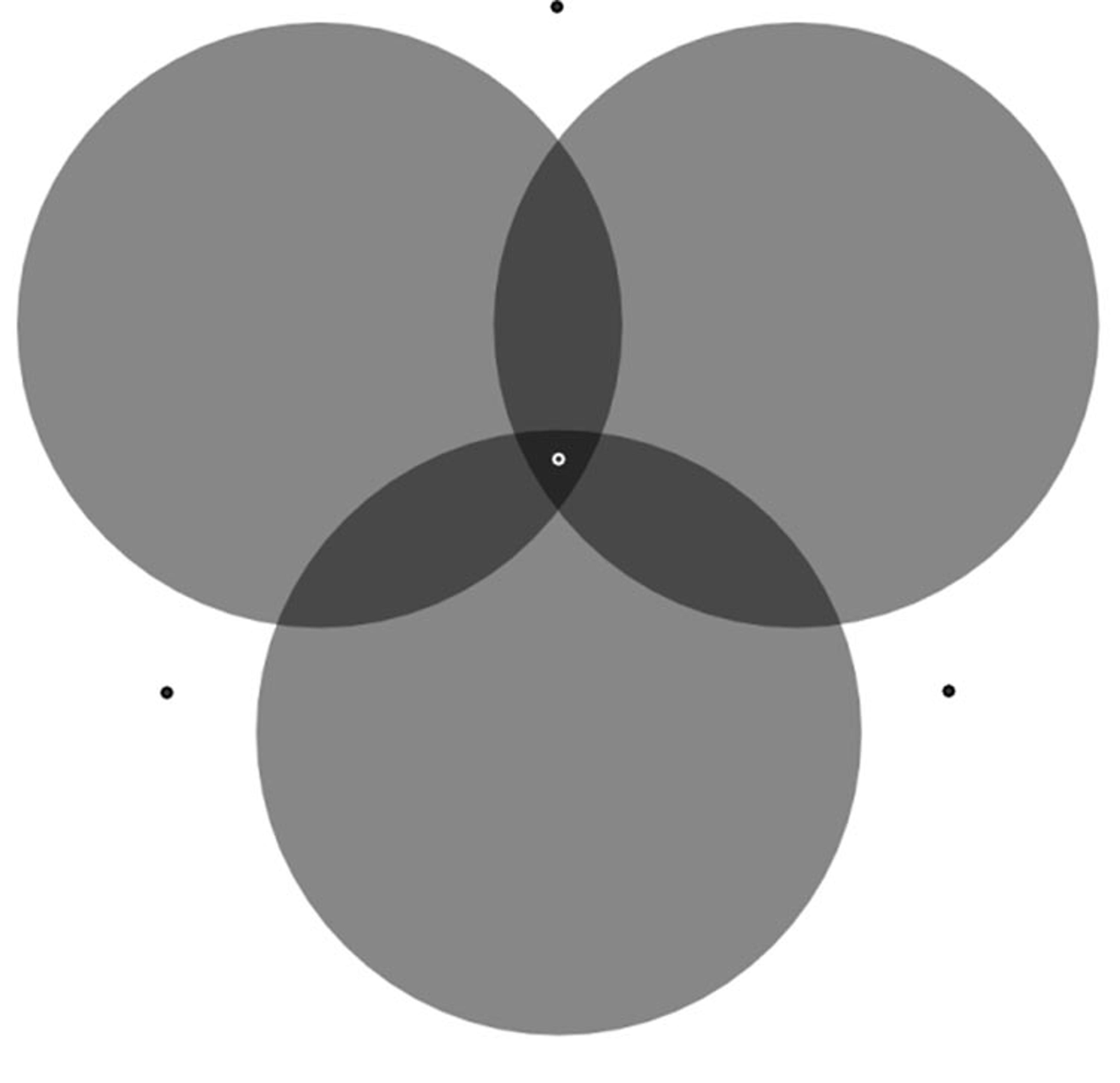

My favourite visual illusion is the Tse illusion below, named after the American neuroscientist Peter Ulric Tse.

Focus your eyes on the white dot in the middle of this image. Keeping your eyes focused there, allow your attention to roam over the large circles that surround that dot. This might take a bit of practice (we’re not generally used to paying attention to something that we’re not focusing our eyes on), but you’ll find that the circle you pay attention to gets darker than the others. I vividly remember first seeing this illusion at a conference about attention. I was shocked. It was as though my attention was reaching out into the world and changing the brightness of objects out there. Of course, that isn’t what’s happening. The circles aren’t changing. My attention is merely making it look as though they are.

Why does this happen? It seems to be connected to the fact that the circles partially overlap one another, against a light background (if the circles are placed on a black background, the illusion doesn’t happen). This causes the visual system to interpret the circles as a series of semi-transparent disks. The visual system then tries to work out which disk is lying ‘on top’ of the others. Attention seems to be one factor influencing this interpretation, but unfortunately it’s still not clear why this would cause a change in the brightness of one circle.

The Tse illusion might initially appear to be just an interesting novelty. But, really, it challenges some of our most deeply held assumptions about the role of attention in our mental lives. We usually think that paying attention to something is a good way of getting knowledge about it. If you want to know more about something, you should pay attention to it and, when your attention slips, you’ll make mistakes. On this common-sense idea, attention is a path to knowledge.

But the idea that attention is a path to knowledge isn’t just part of common sense. It also has a long history in epistemology (the philosophical study of knowledge). The 17th-century French philosopher René Descartes is renowned for his search for knowledge beyond all doubt, and attention plays an important role in this search. He argued that ‘So long as we attend to a truth which we perceive very clearly, we cannot doubt it.’ Descartes’s thought is a pretty strong version of the same idea that’s part of common sense – that paying attention to something is a good means of gaining knowledge about it.

Of course, no one would deny that paying attention to something often helps us to gain knowledge. You’re more likely to solve a maths problem correctly if you pay a lot of attention to what you’re doing. However, the Tse illusion demonstrates that attention doesn’t always help us gain more knowledge, but that sometimes it can distort our perception of the world. It’s making one of the disks look like it’s getting darker, when really it’s not. It’s actively misleading us. This is a problem for our common-sense assumptions about attention, and for the theories of philosophers such as Descartes. In this case, far from acting as a straightforward path to knowledge, attention is making us see things less clearly.

The Tse illusion is just one example of how attention has the potential to mislead us about the world. There is excellent evidence that paying attention to a gap between two lines will make the gap look bigger. Paying attention to an object can make it appear more vivid than objects that we don’t pay attention to. Amazingly, attention also affects our perception of time. Paying attention to a particular event can make it seem to take longer than it really does. This last feature of attention might even be why people often report traffic collisions as happening ‘in slow motion’. If you’re involved in a crash, your attention will be grabbed suddenly and, as a result, you might experience it as taking longer than it actually does.

Taken as a whole, these results suggest that, sometimes, attention can mislead us about the world. This is not to say that attention always distorts our knowledge of the world, but it does suggest that it might not be the unproblematic guide to knowledge that we originally thought. In order to unravel the complex link between attention and knowledge, we might need to change the way we think about both of these faculties.

Taking a step back, perhaps it’s not so surprising that attention can occasionally distort our knowledge of things. We’re all familiar with the experience of overthinking something. If you’ve ever been engaged in a long and complicated project, you’ll know what it’s like to spend all of your attention on one thing, and be left with a vague feeling that you now understand it much less than when you started. Anyone who has written a PhD will certainly know what I’m talking about.

Think about the job that attention has in the visual system. Psychologists and neuroscientists generally argue that attention is there to deal with a problem of finite resources. Our brains can only do so much, and there is far more information available to our sense organs than our brains can fully process. But, of course, not all of this information is equally relevant. In order to prevent ourselves from becoming overloaded by a torrent of information, we need to select which bits to concentrate on. This is the main job for attention: it’s in charge of picking the most important things to concentrate on, and to filter out surrounding noise. On this way of looking at attention, its job is not to get everything perfectly correct, but to select what’s deserving of our limited cognitive resources. What’s most important is that we’re concentrating on the most important things at that particular time. Once we start thinking about attention this way, it’s unsurprising that it doesn’t always get everything 100 per cent right.

As well as tweaking the way we think about attention, we might also need to rethink our view about knowledge itself. Turning away from Descartes, we find other views about the link between attention and knowledge, which perhaps fit better with the Tse illusion, and the other results outlined above. Some philosophers (known as contextualists) have long argued that too much attention can be a dangerous thing for knowledge. According to the contextualists, we have all sorts of knowledge as we go about our everyday lives, but when we pay too much attention to the sources of our knowledge, we find that our faith in that knowledge often vanishes. As an example, return to the visual experience with which we started: of the grass, the café, and the hospital. I normally think that this visual experience gives me good knowledge about the world around me: it tells me that there’s a café there, that the hospital is behind it, and so on.

However, if I think too much about it, I can start to doubt myself. What if I’m having some kind of hallucination? What if there’s no café there, but it’s really some kind of mirage? What if actually, I’m not looking out the window at all, but am really just in a dream? The more I reflect on these increasingly extravagant scenarios, the less knowledge I really seem to have. According to the contextualists, the problem here is simple: I’m overthinking things. If you devote too much attention to all the ways that I could in theory be wrong, then even the most mundane knowledge that we thought we had will soon disappear. The proposed solution is just not to pay too much attention to these kinds of worries.

All of these issues raise some very delicate questions. The contextualists are certainly right that we don’t want to go too far, and end up spending all our time worrying about whether we’re in a dream or not. But then, it’s often really important to reflect on why we hold certain beliefs. This can lead us to revising our opinions, in a beneficial and productive way. What we really need is a way of deciding the point at which attention stops being beneficial for knowledge, and strays over into distorting things. I’m pretty sure that working all this out is going to prove very difficult. But then, maybe I’m just overthinking it.

This Idea was made possible through the support of a grant to Aeon+Psyche from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Foundation. Funders to Aeon+Psyche are not involved in editorial decision-making.