In 1989 I was 11 years old, having recently migrated from Ukraine to Australia. I didn’t have many words in English but I had plenty of feelings, mostly for my classmate Samson Greer. Samson had a sweep of sandy hair and pale-green eyes, and he was kind when others were cruel. This was invaluable to me then, with my limited language and my strange Soviet teeth and third-hand clothes that either revealed too much of my body or draped me like a clown.

One morning I found a $2 coin and knew immediately that I would spend it on a gift for Samson. That afternoon at the local pet-shop, I asked the man what I could get for $2 and he showed me a range of small birds. Before I knew it, he was placing a living thing in a cardboard box, puncturing holes in the top with a screw-driver. Then he taped the edges and we were free to go. Inside, I heard the bird flutter and fight, my sweet new greenfinch, smaller than my hand and bright as a flare.

Walking back to school, I imagined Samson receiving his gift, certain that he’d be where I hoped. And so he was, on the basketball court, lazily dribbling a ball. As I approached, he put the basketball down and tilted his head to the side, squinting.

‘I got you something,’ I mumbled.

‘Why?’ (Though gently.)

‘Just a present, open it.’

And he did, pulling the tape and opening the lid and letting the bird do what a bird will, the moment it is allowed. I wiped my sweaty hands on my too-tight shorts. I stared at the sky, then, mutely at my feet. He held the box for a while, out of kindness, out of bewilderment, perhaps pretending that the box itself was the gift and that was good enough for him.

Thirty-five years later, I tell this story to an old friend. We’re on the Greek island of Hydra for a pilgrimage, visiting the whitewashed house where Leonard Cohen lived in the 1960s. We’re sitting at a bar on the cliff’s edge. It is midnight and the air, still stiflingly hot, is cracked only by the sound of the waves we cannot see. We are drinking mastika, mixing it with fizzy wine, sculling it in shots, smoking cheap Greek cigarettes and tipping sideways in our rickety cliffside chairs.

We toast our ancient friendship, bonds that cross a lifespan. He raises a mystery: ‘What about those connections that persist even when we think it’s over, after our “contract” with someone has expired?’ I keep telling him about the greenfinch, as he orders more mastika, more sardines.

When primary school ended, Samson and I parted ways. Only the memory of that day never left me, imprinting like a bruise. Standing on that basketball court, watching the bird disappear; these images would flash like phosphenes across my psyche over the coming years, visiting me as I entered adolescence, then adulthood, marriage and motherhood.

I snuck out, my stomach inverting itself as I texted the jazz singer

One night, in my early 30s, I attended a friend’s gig, a jazz singer. When she began thanking her musicians, the name Samson Greer rose through the haze, and he dipped his saxophone down a little, but did not stop playing. I wanted both to lunge at the stage and out of the club but, instead, I stood and watched the adult Samson Greer from the back of the bar, simply living a moment of his adult life. He looked different, of course, no longer the lanky, sandy-haired boy. But there was some presence, some continuity in his body language that hit me hard in the chest.

Afterwards, I snuck out, my stomach inverting itself as I texted the jazz singer. I told her the story of the bird, electrified by possibility. The following night, as I was breastfeeding my newborn at some ungodly moonlit hour, I reached for my phone. There was a message from the jazz singer: ‘The greenfinch. He remembers.’

Over the following months, I basked in the curious buzz of Samson’s reappearance, but resisted meeting him. If I’m honest, the greatest thrill was in my friend’s message: ‘he remembers’. Its stark delivery gave my heart what it needed. The bird flew away, but the story didn’t. The moment was humiliating but my gesture was not wasted. The message assured me of my instinct: something that touched me also touched another. Above all, ‘he remembers’ affirmed to me that gesture and beauty matter not because they are rational, but precisely because they are not. My 11-year-old childmind might have been odd, supremely impractical, but my heart knew that this was true.

My friend told me that Samson, too, had married and made a family; that he’d become an accomplished saxophonist. She said he was a lovely man, gentle and modest. He would be happy to reconnect if I wanted to. I didn’t.

By then, the greenfinch had become my go-to tale of minor wonder

In fact, I put Samson out of my mind, this time for about three years.

Then, one night, I attended a gathering in a friend’s sukkah, an outdoor shelter that Jews erect and inhabit for the week of Sukkot to commemorate 40 years of wandering in the desert. The sukkah’s walls and roof are intentionally ‘gappy’, letting in the rain and the stars to evoke the cosmic benevolence that might interrupt our own souls’ protracted wandering and offer a momentary cover from life’s harshness. The sukkah is a symbol of belonging in nature, of our place in greater things.

And so, at this gathering, the host asked us to share a story. By then, the greenfinch had become my go-to tale of minor wonder, if only privately. So I told it, thinking that would be that. Only it wasn’t, because the host proceeded to explain that he was collecting speakers for a weekend of music and storytelling. He handed me the running-sheet, as the palm-fronds whispered above. At the top of the bill, slated to headline the festival, was ‘S. Greer and his Big Band’, ushering in the moment with all the trumpets and percussion it deserved.

My friend and I walk to Leonard Cohen’s house, through Hydra’s tiny streets, curved like arthritic fingers. As we walk, I recall Cohen performing at a vineyard, where he stood like a tiny raven against a buttery moon and serenaded a woman opening ‘like a lily to the heat’. I consider the curve-shaped finger of my own life, my incremental move away from boys and men and the years of inclining, with impossible gravity, towards the lilies.

We arrive at Cohen’s house at dusk, in a moment where every exquisite thing about this place – the bougainvillea, the sashaying cats, the thyme, the honeysuckle, the whitewashed homes with their saffron doors, the dark monastery walls – comes into its purest self, into its truest shape and fragrance. I approach the door and bang the tiny iron knocker, knowing the call will go unanswered.

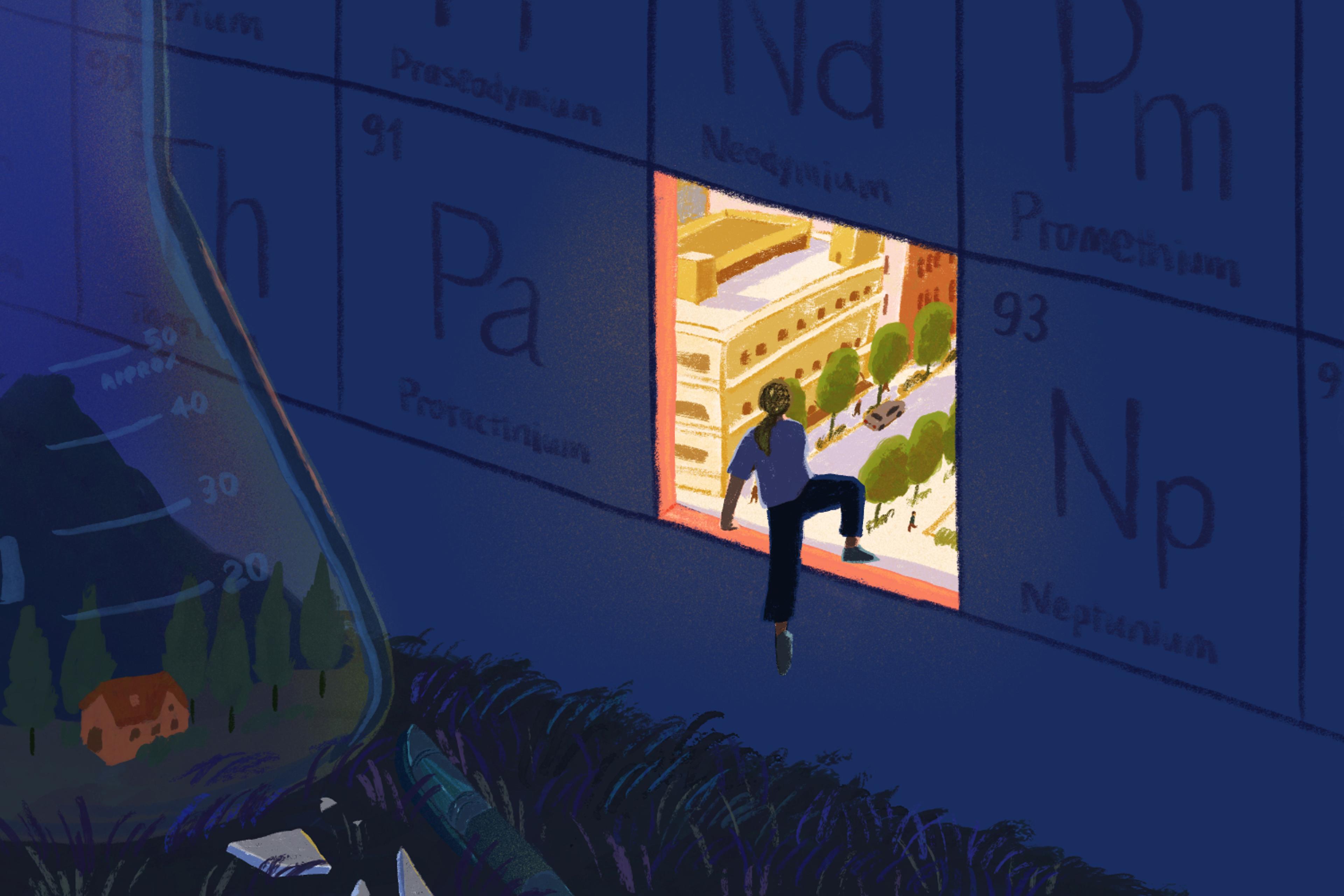

For years, the greenfinch has haunted me, as though its density of symbolism and recursive plotlines must guarantee a meaning. I have refused the possibility that there might be no ‘takeaway’, no narrative coalescence: the idea that some things are neither accident nor design. What I have wanted was a relationship, not between me and Samson but between me and the stories of my life. I have felt that the sequence owes me something, if not resolution, then a modicum of care. This is what I tell my friend as we stand at Leonard’s door, as I deliver the last installment.

At the festival, I listened to Samson’s performance with my guts in my throat. I watched him exit the stage and pack away his saxophone. Then, with a cadence not dissimilar to the first time, I marched towards him and spilled out a fragile but sincere thing. I told him my name, and that I was the girl who once gave him a bird on the basketball court.

He looked at me. Closely, calmly. Then he said: ‘You’re going to have to forgive me.’

‘Why?’ I said, suddenly panic-stricken.

Even though we were virtual strangers, Samson Greer caught my plummeting heart

‘I have a terrible memory for faces… you don’t look familiar to me at all. I don’t remember your face from that time, I can’t connect it.’

‘Oh,’ I said, pushing down tears. But even though we were virtual strangers, Samson Greer understood me, caught my plummeting heart.

‘No, no! I mean I don’t remember your face, but I remember everything else. I remember the bird, and the basketball court. I remember thinking how nice it was that someone brought me a gift. I didn’t quite get it, but I liked it.’ As he spoke, I was struck by the multi-coloured palette of his eyes, which I’d encoded as solid green. In fact, they held a range of nature’s offerings; a splash of sea, a swathe of sky.

‘What does it all mean?’ I said, recounting the jazz gig, the sukkah.

‘I don’t know,’ he replied. ‘Maybe something about surprises… This is a nice surprise and those are important, don’t you think?’

As I stand at Leonard Cohen’s door, the greenfinch revisits me with renewed force. I feel the disparity in memory, the way that Samson recalled the little bird, but I carried it, held it like a key to some original self. I think about the human need to narritivise, to connect parts into a whole.

Of course, this leads me to Cohen’s much-quoted line that there is ‘a crack in everything’. While I admire it, it has never been my favourite. I adore ‘every heart to love will come, but like a refugee’. Refugee, refuge, fugitive – each of these words shares the Latin cognate fugit – ‘flight’.

On the steps of Hydra, on its tiny corners, around their bends, there is no reckoning. I take just a moment’s pause on tempus fugit, the flight of time. This is the nature of our lives, and our loves: they are fugitive, always flying up and away, like the crash of a wave, like a gift, precious not because they last but because they are given. Tomorrow we will leave the island, fresh with farewells, open to surprises.

Some names have been changed to protect people’s identity.