I try to keep the initial chat brief. If someone’s interested in working with me, and I have room to bring someone into my therapy practice, I suggest we connect by phone and do a preliminary exploration of the fit. After all these years, I can usually tell pretty quickly if the match will work. Basic courtesy and a degree of enthusiasm are good signs. Any sense of humour is a bonus. I’ll almost always begin the call by asking the same question that I now ask John: ‘How might I be able to help you?’

‘Well, Eric,’ John begins quietly and rather sweetly after a little pause, ‘I’m 53 years old and I don’t think I’ve ever told anyone this, but I don’t think I’ve slept all the way through the night since I was seven years old and learned from my Uncle Phil that death was real and was coming for all of us. Some part of me is still seven years old. I think it’s time I turned towards this thing.’

We schedule for Thursday at noon.

On another day, as I look through the light rain out my kitchen window, I see a crow – still as frost atop my mossy cedar fence. I have a strange feeling that I struggle to understand.

We feel so many things at once. There’s rarely a single word for the layered emotional shifts of a moment, and this one is no exception. With close attention I can pick out some of the tones: in the simple fullness of the moment, there is calm; in the beauty of it, there is something more than appreciation and something less than joy; in my ability to notice this beauty, there is self-satisfaction; in noting my self-satisfaction, there is embarrassment and disappointment; in the light of the sheer undeniable fact of my equality with the crow, there is humility and belonging; in the unbridgeable chasm between us, there is loneliness.

And unmistakably, there is sadness, and envy. What is sad? What do I envy in this crow?

I can’t put my finger on it, and in the days following, driving in my car, washing up, randomly (as all thoughts come), my mind falls upon this chasm between me and the crow. The crow belonging to one realm, I to another.

I am only a visitor, a stranger in a strange land, a temporary interloper

Then, during a session, a client describes hearing loons across a lake in Vermont – the eerie call pulling her not just into childhood, but, she says, ‘to the beginning of all things’.

There it is: my crow, it seems to me, has been here since the beginning of all things, is still here and always will be. He isn’t just in the world; he is of it. I am only a visitor, a stranger in a strange land, a temporary interloper standing briefly between infinitudes of non-existence. The crow will live forever and I will die, and I know it.

But even as that thought solidifies, my recognition of its absurdity follows. The comparison is faulty: the single crow on my fence, I see most saliently as a timeless crowing; myself, I see as singular, atomised, a thing called ‘Eric’. Crowing is an eternal, mysterious, natural event; ‘Eric’ is a thing that was born into this world and all-too-soon will leave it.

Why should I see myself as the fixed one, even as I see the crow as a naturally unfolding process? What stops me from seeing myself in the same light? What claim to the eternal do I grant the crow that I deny myself?

How many problems vanish when I can see myself as I see the crow.

It’s noon on Thursday, and I open the door to my waiting room to greet John. (John’s story is loosely based on a real therapy client; details have been added and altered.) I can see right away that I’ll easily feel affection and empathy for him. Even sitting in his chair he is noticeably strapping, at 53 thicker than he likely once was, but clearly still powerful and kinetic. He stands quickly and almost embarrassedly, as though I’ve caught him doing something, and I can see he is several inches taller than me, thick grey hair, T-shirt and jeans, his big eyes sweet and rather sad.

We shake hands warmly, and I feel how strong his hand is, and how clearly he’s held back from uncomfortably squeezing mine. It suggests a lifetime of being mindful of his own natural power, and a kind heart.

‘Welcome,’ I say. ‘Come on in.’

I feel such instant rapport with John that there seems to be little need for the pleasantries and lightnesses with which I typically begin new therapy relationships. I gesture to the couch for him to sit down, take my own seat and, still smiling, get right to it.

It’s like turning off a light in a room no one goes into again

‘So tell me about death, John.’

He chuckles. ‘I guess we’re jumping right in, eh?’

‘Should we talk about the Yankees?’ I joke.

‘Ha, I guess not,’ he says, and looks out the window for half a minute. I can see him settling in quickly. ‘Fucking Uncle Phil. He was always giving me more than I could chew.’

More silence. I invite him to continue.

‘I was seven years old,’ he begins quietly. ‘Hated going to bed. Hell, I still do. It was Saturday night, and my parents and Uncle Phil were watching The Love Boat. My mother was trying to get me moving towards bed and I was making some sort of fuss. And Uncle Phil said, “No big deal kiddo, odds are pretty good you’ll wake up.” I didn’t get it. So I asked what he meant. “I mean you’re just going up to bed, little guy, not the grave. I bet the lights will come on in the morning. I’ll make pancakes.” Then he turned back to The Love Boat, like he hadn’t just kicked open a trapdoor to a nightmare in my head. I don’t think I closed my eyes that night. How could I know the lights would come back on? And, man, after all these years, a wife, my own kids, a successful business, a part of me still is lying in that bed, terrified of what’s waiting for me.’

‘What’s waiting for you, John?’ I ask. ‘What’s death like?’

John looks out the window again. ‘It’s like turning off a light in a room no one goes into again.’

I’m down in my basement, looking for that D battery I know I have somewhere. What is this feeling now, as I come across a once-cherished cassette tape? If you’re a certain age, you know the feeling well enough already. There’s no way to play this relic, and far more than that, there’s no way to be the person you were when it once meant the world to you.

‘A Case of Mistaken Identity’ by Alan Watts, the tape label read. A lecture he gave, I believe, from his houseboat in Sausalito in the 1960s. How lost I was, how utterly disoriented, when it fell into my life, a gift from the father of a girlfriend, his handwriting on the label of the cassette at once so familiar and distant.

I don’t need a tape deck to have one line immediately come back to me in Watts’s raspy, mischievous voice, as I remember it: ‘We are not things that behave, but processes that proceed.’

If I wasn’t a fixed, knowable self, then I hadn’t failed to be one

What a relief that was for me! The first time I heard it, driving in my Subaru, west of Tucumcari, headed nowhere in particular, it clicked with all the ease and satisfaction of a puzzle piece. What a gorgeous reprieve for that befuddled young man who felt not only the pain of having no clue how to engage the machinery of society, but more than that felt the utter shame of failing to be someone. The trope is familiar but apt: a thoughtful young man who’d gotten off the bus of professional development, travelling the earth to find himself, like the self was an object I might find under a rock far from home. Who am I? What thing am I? Well, shit, I had no idea.

Watts’s phrasing offered me something radical in its simplicity: the possibility that I wasn’t a solid, separate ‘thing’ at all, but an unfolding, a movement. A happening. I didn’t know it at the time, but this echoed a lineage that runs through Heraclitus (‘You can’t step into the same river twice’), early Buddhism’s doctrine of non-self (anatta), and process thinkers like Alfred North Whitehead (‘There is no nature at an instant’) and William James, who in The Principles of Psychology (1890) described living beings not as fixed essences, but as ‘bundles of habits’.

The implications to me were helpful beyond measure. If I wasn’t a fixed, knowable self, then I hadn’t failed to be one. And if I was an event in motion – like a breeze, or a flame, or a wave – then I didn’t need to locate myself. I could start to imagine my personhood not as a thing but as a roiling together of body and breath, memory and mood, ceaselessly shifting thoughts and perceptions, all braiding with the rest of the world in a pattern that could never be repeated.

Father, husband, psychologist: these are roles that I show up for, and I try to show up well, because as emergent properties of my living, they are there waiting for me each day. But what am I? Apparently I am a process, continuing (for now) to proceed.

How strangely silent we are around death. Not in the literal sense – obituaries, rituals, condolence cards – but in the deeper way that would bind our experience: a common language close at hand and easily offered, a shared way of seeing that might help us more deeply regard dying as normal and natural. We mythologise, or we lean on a mutually supported denialism built on distraction and, for the more egoistic, notions of ‘legacy’. Mostly there is silence on the topic, and when the silence breaks, without a shared spiritual or intellectual context, what emerges is often fear, or confusion.

In the quiet of the therapy room, this shows up in small, urgent ways. A client will pause, lower their voice, and confess not just the grief of losing what’s loved, but a kind of existential terror. Not about someone else’s death, but about their own vanishing into the void, so total it short-circuits imagination.

This was at the centre of John’s pain. What haunted him as a child continued to haunt him as a grown man, as it does so many of us: being alone, forever, in that lightless room. For many, like John, that metaphor captures the image quite literally; for many others, there is an unarticulated, gnawing and profoundly disquieting notion of some kind of state of non-existence.

I’ll often ask what year a client was born. ‘1949,’ they might say. ‘And 1948?’ I’ll ask. ‘How was that?’ Usually this leads to a chuckle, and maybe a hint of relief.

But with John, it didn’t quite land.

We don’t consider where yesterday’s thunderbolt has gone

‘It’s different now,’ he said. ‘Now I know I exist.’

And so we went deeper – not directly towards comfort, but towards clarity. What exactly was it that John believed would be lost? What was this ‘thing’ he called himself, this entity that would someday ‘be dead’?

Piece by piece, the ‘thing’ he was began to dissolve. Not into nothingness, but into motion. What emerged instead was a stream of processes: memories, roles, gestures, the way he held himself back from crushing a handshake. A life not as an object, but as an unfolding.

As our work continued, he didn’t stop being afraid. But something in the shape of the fear began to shift, and ultimately to lighten. ‘I still get scared,’ he told me, ‘but I think I thought I was going to disappear like a statue being knocked off a ledge. Now it feels more like I’ll just… stop happening. Like a breeze.’

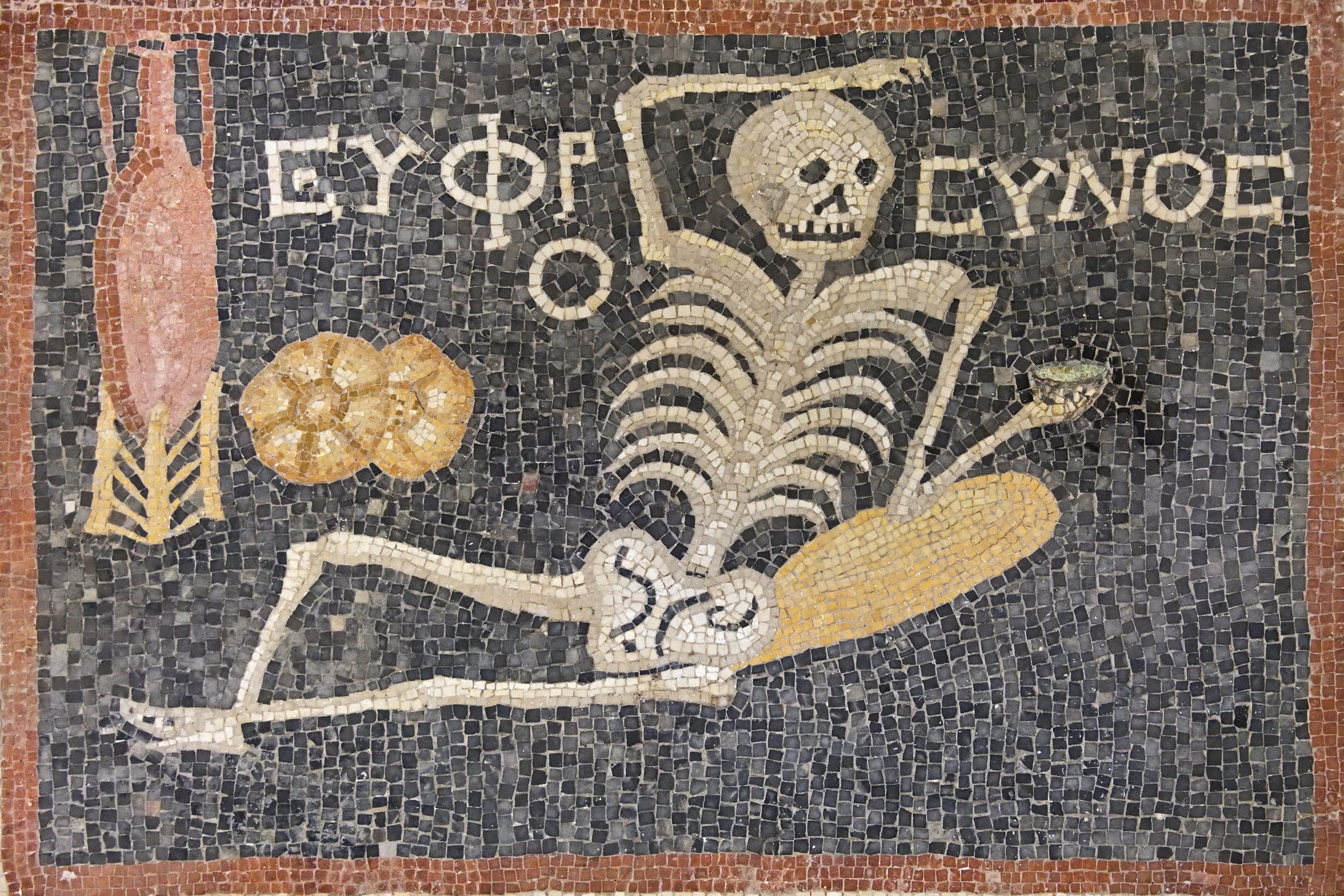

The language of death can be enormously confusing. ‘Grandma is dead,’ we say. But in fact, no, she is not. Right now, there simply is no Grandma. The sentence collapses.

We describe people, and therefore think of people, as nouns. ‘Grandma’ is a kind of thing. There is Grandma in her chair, and then she dies. Where did she go? Our premise of object constancy demands we place her somewhere. Heaven, hell, the void.

But Grandma was never a thing. She was a verb the entire time. A miraculous harmony of processes – eating, laughing, noticing, forgetting – that one day stopped happening. We don’t consider where yesterday’s thunderbolt has gone.

Many of us mistakenly think of death as the opposite of life: life is a state, so death must be one too. But death isn’t the opposite of life. It isn’t a state at all. It exists only as something we imagine, as an idea, which means it exists only within life. It’s not an experience we have, but a noun we invented to describe the ceasing of a verb.

John came to me afraid he would be dead. The statue knocked off a ledge exists in some state, somewhere down below. But slowly he began to see that what he feared so greatly was an experience. And that death, in the end, isn’t one.

And once the verb of living ends, when the breeze settles, well… how was 1948?