When Dad’s health was failing in his 90s, he hired a live-in caregiver named Gracia. At first, she seemed a godsend – warm, attentive, a good cook – and he urgently needed the help; he had agonising osteoporosis, and walked with his back bent so far forward he always seemed about to fall. A Green Card-holder from the Philippines in her mid-50s, Gracia was bubbly and garrulous like my mom had been, and claimed to be a devout Christian. But her cooking was so spicy it gave Dad the runs, and she left fruits and vegetables out so long that they drew fruit flies. She yakked nonstop, and let us know that those not chosen by God – Jews like us – were damned.

She never talked that way to Dad, of course. ‘Just you and me against the world,’ I heard her say once smiling, leaning in close. He smiled back.

‘That’s not right,’ I said. ‘You’re telling him no one but you cares about him.’

‘He is my boss, not you,’ she answered. ‘I am here every day, and you – big blue moon.’ In fact, for years now, my wife Pam and I had spent every vacation day flying back and forth between New York and Los Angeles to take Dad to doctors, hospitals and physical therapy centres.

Soon after Gracia started, Dad informed us that he wanted to update his will, written before my mother died, to make certain I was his beneficiary and heir to his house. He’d designed and built it himself decades ago and, though falling apart, it was his second, favoured child, the one he never wanted to let go. I was surprised – I’d long since thought he’d leave it to his girlfriend Muriel, whom he’d met at a grief group after my mother’s death.

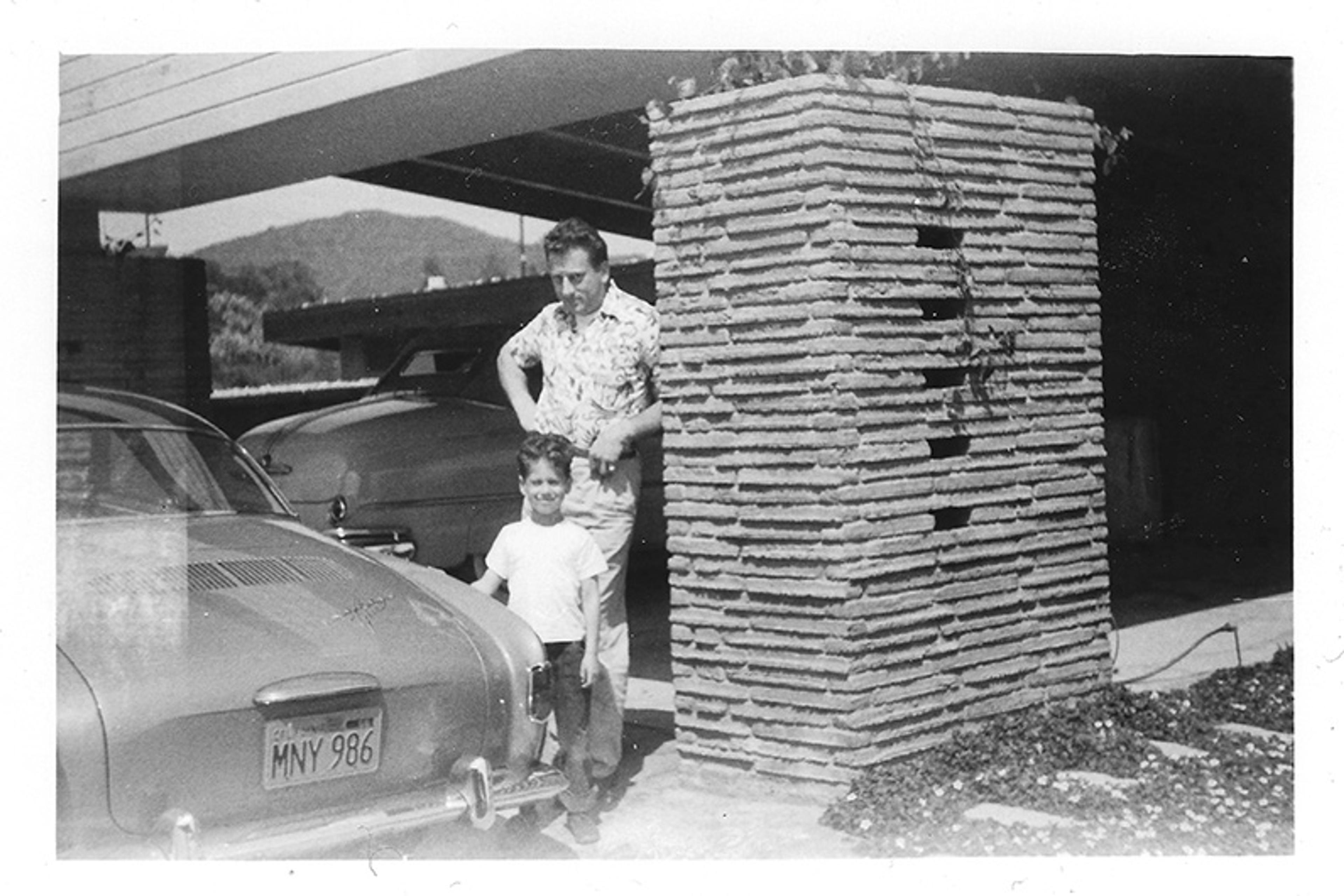

The author with his father in the Santa Monica mountains, Los Angeles, 1950s

After all, I’d always pissed him off. I was his only child, but not the obedient, admiring son he wanted, and I overtly resented the countless weekly hours of gardening and housework he demanded of me while I still lived at home. His rage sometimes boiled over into cruelty – he’d wash my mouth out with soap, whip me with a bamboo stick, or simply terrify me with his favourite threat: ‘One more word and I’ll break your jaw.’ That always worked, because I thought the splinters could fly up into my brain and kill me.

His words were so vicious, I hung up on him. After that, he refused to answer the phone

I’d outgrown my defiance by junior high. As the years passed, I climbed a ladder of academic and professional success, married and raised two sons. Despite all that, at the slightest perceived provocation, he would snarl: ‘You were a hateful kid, and I’ve never seen anything since that proved otherwise.’ I don’t think I was actually hateful as a boy, but because he so often criticised and glared at me, my happiest moments always came when he headed off to work the night shift. As an adult, my dominant emotion around him was a longing for love and acceptance that had never come.

The old patterns flared up again just months before he hired Gracia, when he launched into a diatribe about my older son based on a grandparent-scam phone call he’d gotten asking for money to bail him out of a nonexistent jail. He’d believed it, but declined to pay anyway, and his words were so vicious that I hung up on him. After that, he refused to answer the phone whenever I called.

Despairing of ever talking to him again, I appealed to Muriel’s good graces. She was thrilled to hear from me. It turned out Dad was back in the hospital, and she felt too old to be responsible for him. When I called his hospital room, I heard him scream, his words slurring narcotically: ‘I don’t wanna talk to him or his shtupid shun.’

Muriel worked on him, and I resumed visiting him in LA. But Gracia kept working on him too. One day, Dad told me he had fired Gonzalo, his gardener, handyman and friend of 30 years, because Gracia had told him Gonzalo was stealing food. It turned out Gracia’s husband José was a gardener, and he soon took over Gonzalo’s job, moving into Dad’s house with her and bringing the family dog. Not only did he have free room and board, he also charged Dad more than twice what Gonzalo had earned for much less work. Dad was stunned when I pointed this out.

Two things seemed evident: Gracia was something of a con artist, and something was wrong with Dad. When I informed José we were reducing his salary, he instead moved out, and when I flew to LA to find another gardener, I looked over Dad’s financial records and discovered he could no longer do mathematics. This was a man who had worked for decades as an engineer; he’d done the complex blueprint for his house before building it almost singlehandedly. When I broached seeing a neurologist, Gracia overheard and responded indignantly: ‘I would never insult my father like that.’ She convinced Dad to refuse, telling him I’d use a dementia diagnosis to put him in a nursing home.

He’d only fantasised the investment of $30,000 and the sales job

After I returned to New York, crestfallen, I got a call from the weekend caregiver. ‘Your father’s hallucinating,’ she told me. Gracia had taken Dad to a meeting about buying into Subaru dealerships, and when the weekend caregiver showed up, he told her he’d invested $30,000 and was now selling cars. When I talked to Dad, he insisted it was true.

‘You’d be surprised by what a great salesman your old man is,’ he said. But he’d only fantasised the investment and the sales job.

I hurried to LA, and this time I convinced Dad to come to UCLA Neurology as a favour to me. After hours of testing and days of waiting, we got the diagnosis: Alzheimer’s.

Perhaps sensing that she herself was running out of time, Gracia launched a campaign to divide and conquer. One day, poking me in the chest, she said: ‘Muriel don’t have sex with him no more. You have to get him a woman.’ I suspected her goal was to chase Muriel out of Dad’s life, so I told Muriel what she’d said. Then, I learned Gracia had been feeding Dad – and any neighbour who’d listen – ugly lies about Pam and me. ‘They’re going to tear your house down, sell the property, and take your money,’ she told him. When he confronted us, we told him we’d never said anything of the sort – and would never force him out of the home he loved so dearly.

After Pam politely declined Dad’s offer of my mother’s old clothes, we gave them to Gracia, who shipped them to her home in Arizona, then told Dad Pam had stolen the clothes. After that came the jewellery. Years ago, Dad had given Mom some expensive pieces, and when Dad couldn’t find them, Gracia told him Pam had stolen those too. He called me in New York, enraged, and said he was thinking of rewriting his will again, leaving everything to the motion picture industry (where he’d worked most of his career) – because, though he valued all I’d done for him, he couldn’t leave anything to a man whose wife was a thief.

That old umbrage of mine – at my father’s dismissiveness and distrust – was now bursting at the seams. But I told myself it was the Alzheimer’s making him so vulnerable, and that it was Gracia who was depriving me of the chance to keep healing a lifetime of scars with him. I reminded him where we’d hidden the jewellery, months back when he didn’t initially trust Gracia. But he couldn’t follow my phone instructions, so I flew 3,000 miles, met him in his bedroom, and we located it together. Later, Gracia told him I had sneaked in and planted the jewels to cover for Pam.

It was painful for him to process, but the words ultimately rang true

The clincher came when the weekend caregiver called again with yet more alarming news: Gracia had proudly informed her that Dad was planning to leave her his house and money. That’s when we knew we needed a lawyer. I first spoke with aggressive attorneys who favoured going to court, highlighting Dad’s dementia to preserve the estate. But Dad and I had had enough wars. I settled on a counsellor known for making peace.

We came up with a plan. Muriel agreed to host a strategy session at her home, including Dad. The weekend caregiver came, along with other fill-ins she knew. One by one, Muriel, the caregivers and I explained to Dad what greedy machinations Gracia had been up to. It was painful for him to process, but the words ultimately rang true. We set up a schedule with these caregivers to take over Gracia’s hours.

We thanked Gracia for her service, gave her a face-saving reason for dismissal – Dad now needed caregivers trained in memory care – and offered six months of severance as well as a month to move out. She just had to sign the papers. Days passed. The new caregivers took over. We changed the locks, but Gracia kept trying to sneak into the main house. When she heard Dad in the bathroom – a few feet from her quarters – she’d knock and beg him to let her in to talk. But Dad, scared of her now, never opened the door.

Finally, she signed, took the money, and left our lives.

From that day on, I tried to be the son Dad never thought he had. We continued taking him to medical visits and Veterans Association events like memory groups. I got him hearing aids. I put in an electric stairlift outside so he wouldn’t fall to his death trying to negotiate his steep front steps. We paid all his bills and filed his taxes. In the last year of his life, Dad thanked me constantly. The effusiveness embarrassed me but I could only hope I was finally proving the devotion and respect he’d never felt I showed him growing up. On our last Father’s Day, I took him to the battleship Iowa, now a floating museum in the Port of Los Angeles. During the Second World War, he’d worked as a precision machinist at the Brooklyn Navy Yard. After Pearl Harbor was bombed, he enlisted and was stationed there, rebuilding battleships – including the Iowa. I told the museum curators his story, and they gave us a private tour. As I wheeled him around, I saw something I’d never seen before: tears in his eyes.

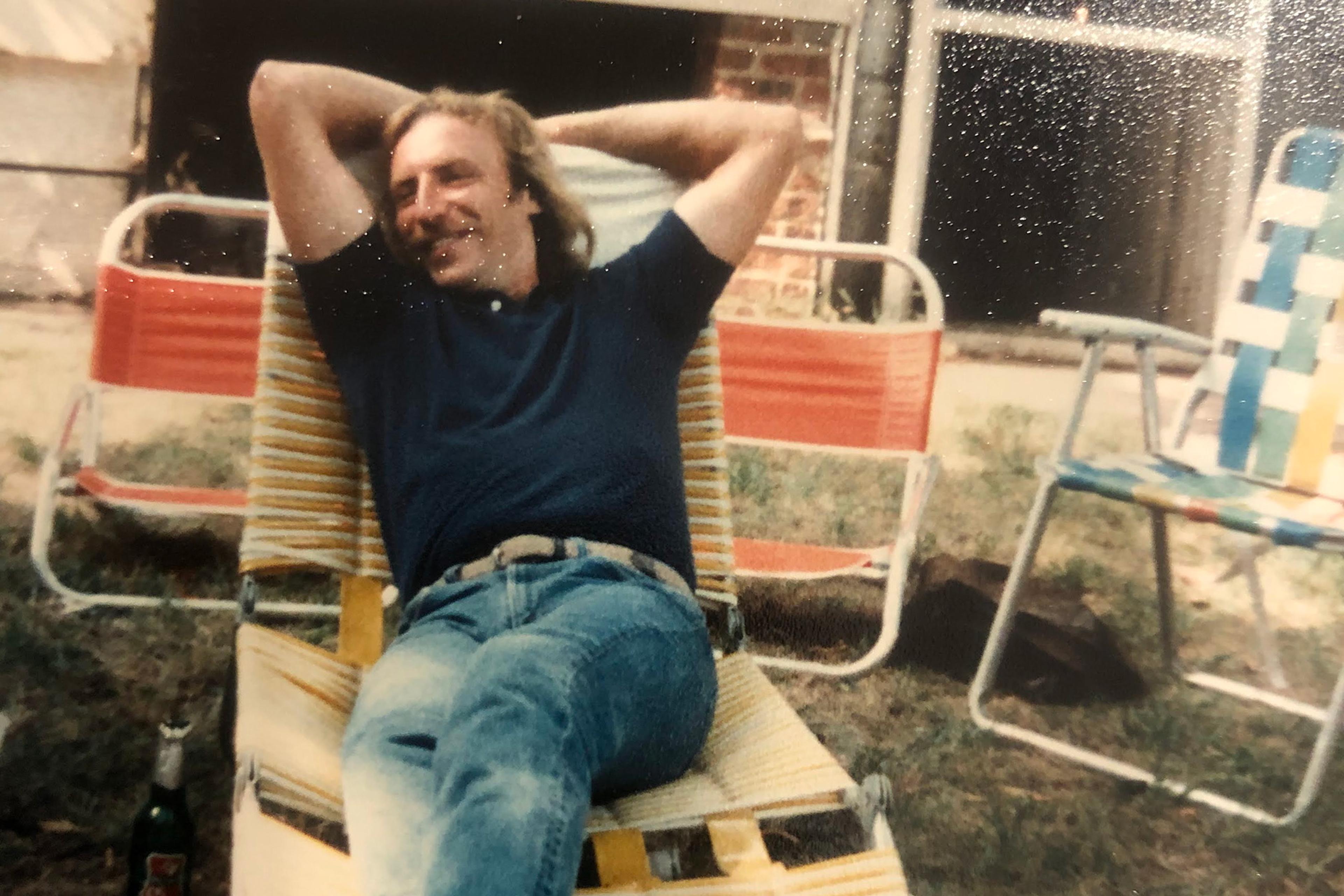

The author’s father, c2015

In 2019, his house was caught up in one of the California wildfires, and a neighbour braved the smoke to carry Dad out. Dad’s caregiver drove him to the VA hospital, but he lasted only 10 days. I petitioned the navy and, at his funeral, a two-person honour guard played ‘Taps’ and ritually folded the flag, handing it to me.

Pam and I spent the next three years restoring the house, and now we travel back and forth from New York to LA to enjoy the home he and we built, in the neighbourhood he enabled me to grow up in. With its mid-century modern architecture faithfully preserved, the house is my link to him. Each time I return, I remember the hard-earned discipline and work ethic he taught me over my objections, which in the end served me well. I’m over the resentment, but I still feel regret. I could have learned so much more from him. What a waste.