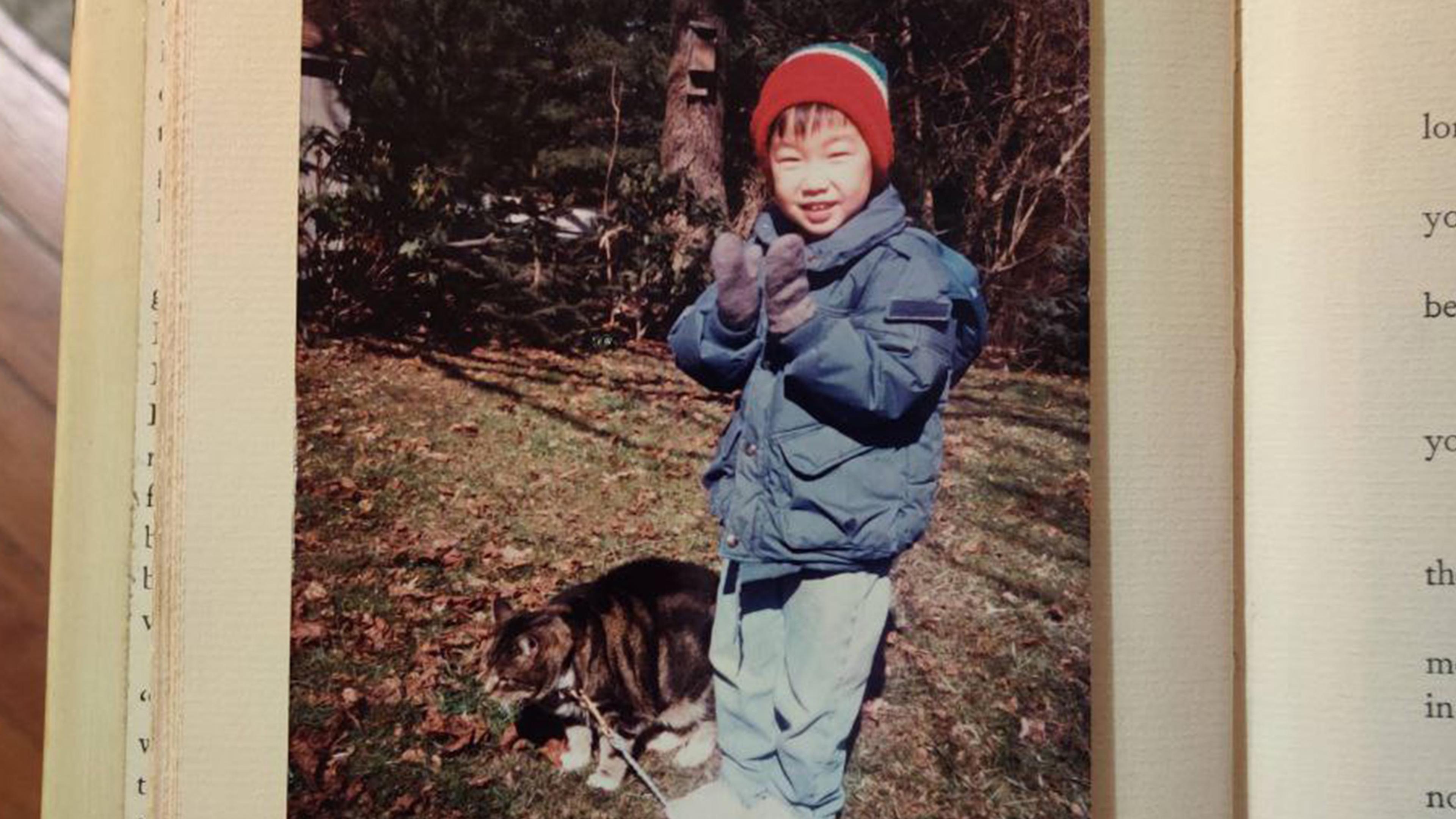

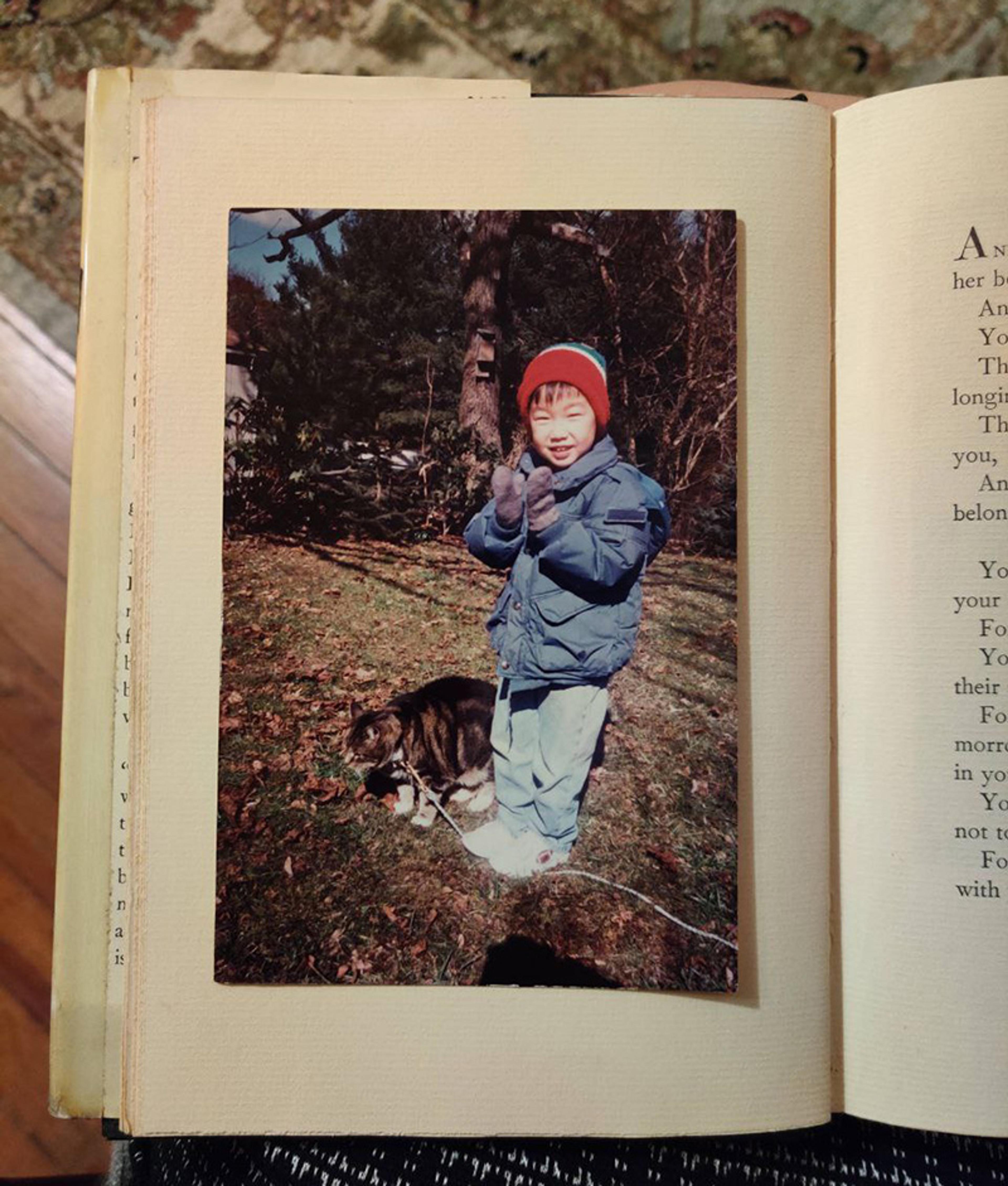

I’ve been reminded of my good fortune countless times, by new acquaintances and old family friends, store clerks and neighbours. ‘You’re so lucky,’ I am told. ‘You must be so grateful.’ The first time must have happened before I was old enough to remember, expressed over my head to my adoptive parents. Growing up, I could never tell if it was supposed to be a congratulations or a demand.

‘You’re so lucky’ is the second-most common response when somebody learns I was adopted from South Korea. The first is a question about when I found out. But I’ve always known. It was in pre-kindergarten that I learned that I was different from the other kids in my majority-white suburb. It was in elementary school that I learned that my difference made me worse. But my parents were commendably open about my adoption from when I was old enough to know what it meant.

They wouldn’t have been able to keep it secret for very long. I don’t look like my Caucasian mother or mixed-race father. He was himself adopted to the United States as a Korean War orphan at seven, old enough to remember the hunger, old enough to remember foraging for spent shell casings to sell as scrap metal for food, old enough to remember the trauma and relief at being transported to a mid-Atlantic life of abundance, after which he would never speak a word of his native tongue again. He, too, was told he must be grateful. When he was old enough, he vowed, he would adopt another child like himself.

He grew up and fulfilled his promise, and for that reason I am the person I am today. I know that keeping that commitment was important to him. I do not know the precise reasons he was never able to keep a job, or why his sentences started with intention and ended in confusion, or why he flew into unaccountable, apocalyptic rages. He ought to go into the woods, he would thunder, and just die.

These episodes were like the passing of a storm, my mother would explain. Just wait for them to end. This was one of the rules she lived by, and she was a woman who loved rules more than she loved people. I do not know the reasons for her coldness any more than I know the reasons for my father’s rage. But I knew from my early childhood that something was amiss.

I was left with a lingering scepticism about the concept of family in general

Things didn’t fall apart until my father unleashed his customary rage at my partner, and what I had naturalised and explained away for decades finally appeared as ugly to me as it always had been. We attempted a year of family therapy; an entire revolution around the Sun of mid-pandemic Zoom mediations in which we too spun in circles. In the end, my adoptive parents chose their pride, propriety and anger over me.

I was relieved, eventually, but first I was bitter. The sheer randomness of the adoption process had long chafed at me. Many people experience difficult family dynamics, but the mechanics of adoption present an additional difficulty. If I were one spot later in the chain of adoptable children, I could have been raised as an entirely different person. A different surname, nationality, and family – perhaps one that would still be intact today.

By the time my adoptive family fell apart, I had learned that the international adoption system was rife with abuse. From my father’s generation through my own, more than 200,000 Korean children were sent to the US and Europe for adoption, all from a country the size of the state of Kentucky. Some of us were indeed unwanted orphans, given up by our birth parents in hopes we’d have a better life. Some were actually kidnapped off the streets, while others were taken from unwitting birth parents after their falsified deaths, or sourced from the internment camps where the South Korean military government stashed ‘vagrants’ and other undesirables. In March this year, South Korea publicly acknowledged widespread fraud across the mass adoption system for the first time.

Even learning these facts as an adult felt dirty, subversive, like a kind of intellectual ingratitude. And there is nothing worse for an adoptee to be than ungrateful. But this is the nature of the system that I and my adoptive father were both victims and beneficiaries of. In the wake of my adoptive family fallout, I was left with a lingering scepticism about the concept of family in general.

And then I met my cousin.

Last year, I mailed a DNA sample to 23andMe. I wasn’t looking for family, only genetic predisposition to disease: I felt a nagging uneasiness each time I filled out the family medical history section on a doctor’s intake form. I received my unremarkable results and thereafter would receive periodic email updates from the service. None were extraordinary until one email turned my world upside down.

My partner, who had soldiered through the interminable year of family counselling alongside me and was therefore quite attuned to my complicated feelings about family relations, was the one who caught it. I saw them looking at an open email tab on my laptop’s browser with a look of evident trepidation.

‘It’s about your DNA test results,’ they intoned in response to my visibly growing concern. At that moment, I was sure I’d been diagnosed with some devastating, incurable hereditary condition, probably with months to live. But the email was about a family match: a biological first cousin living in the Midwest who, like me, was adopted by an American family. Her name was Anna. My first blood relative.

Perhaps family was something I craved after all

My partner cautiously asked me if I wanted to reach out. I could have invented a hundred reasons not to. The memory of my adoptive family’s slow-motion implosion was still fresh; a random stranger wouldn’t magically become family just because we happened to share a portion of genetic material. But I wanted to try. I’d never thought I would ever meet a blood relative.

Three decades after two siblings, our respective parents, relinquished us both, we cousins saw each other for the first time through a video conference call. Imagine a remote job interview combined with getting cornered at a family reunion by a distant relative you’re supposed to be familiar with but about whom you can recall precisely zero information necessary for a cordial conversation. Then throw in the terrifying randomness of speed dating and the anxiety-inducing stakes of a make-or-break test.

Our first call, all things considered, went well. Neither of us vomited or fled the call in terror. We exchanged pleasantries and compared our lives, which are in many ways quite different. I would learn that faith was a central pillar of her life, while mostly absent from mine. The political organising that grounds me is foreign to her. She continues to live in a predominantly white suburb like the one I left as soon as I could. Her friends are heterosexual couples raising children in single-family homes. Mine, largely, are not. At times, our lives feel almost as different from each other’s as they are from the lives we might have had if we had grown up together as cousins in Busan. But the most important thing that came out of our first halting exchange was a commitment to continue. Perhaps family was something I craved after all.

My partner and I flew out to Minnesota to meet Anna, her husband and their daughter last summer. Later, they came to Philly. We took them out for water ice; she gave us advice on making hotdish. We exchanged family stories and everyday life updates. It’s a unique experience: to be most of the way to middle age before starting to piece together something most people take for granted. To write a large part of my story before revising it to add a subplot typically introduced in the first chapter. To be in your 30s when you first notice how another person’s facial features echo your own. To begin a new consideration of what family can and might mean.

I am honoured to call Anna family, and not just because of genetic test results

I love my cousin and her family, who are generous, considerate and kind. I’m even starting to love myself, a task made harder for those of us raised in a culture designed for others, one that can frame us as trophies or charity cases. Today, we are both reconsidering what our identities and selves can mean beyond such impoverished narratives. We would later speak of the questions regarding our adoption, questions my cousin had not previously asked herself. That two siblings both gave up their biological children within a few short years of each other certainly raises the spectre of malpractice or worse. Such considerations were a terrible shock to my cousin, though ones I tried to raise with compassion and care. I tried to speak with candour about my complicated thoughts about the international adoption system and to listen as she worked out her own.

I now know myself as an immigrant from a formerly colonised country, if one raised speaking English by suburban citizens; as an internationally displaced person, if among the most fortunate; and as an East Asian person from the Global Majority, albeit one who sticks out in old family photo albums. I have fought to begin properly loving myself and those close to me, a choice that has exacted certain costs: the comforts of old stories, some privileges of adjacency to whiteness, and my relationship with my adoptive parents among them. But these are the only terms on which I have found dignity and self-love possible. They are the terms on which I can orient the body I inhabit, the experiences I carry – and the sense of family and community I wish to build.

I am honoured to call Anna family, and not just because of genetic test results. Families are not only what we’re born (or adopted) into – they can be chosen and consciously created. Indeed, my relationship with my cousin is both. Our hereditary connection was the beginning of a bridge we are building together. We are constructing a sense of trust and care as we share stories, compare traditions, and learn: about our histories, our dreams, each other, ourselves.

Happening to meet a biological relative as loving and considerate as my cousin has allowed me to understand that family is a gift. The fact that not all gifts are well-intentioned or beneficial does nothing to cheapen those that are.