One night in December 2013, I had a long chat with my mother on the phone. An hour later, she rang back and left a strange voice message while I was brushing my teeth.

‘I just wanted to know whether you’ve got a key so I can go to bed,’ her message said.

I rang straight back to remind her that I wasn’t coming until Thursday.

‘No, that’s not right,’ she said. ‘You were here tonight. The two of you left together, you and Ina.’

The strange thing wasn’t that my mother had just had a visit from me in her home on the small Danish island of Fanø, when in reality I was hanging around my apartment in Copenhagen. It was more hearing myself spoken of in the plural, as part of ‘the two of you’ that had just left. Me and myself.

Maybe my mother had had a drink or two. Maybe she was thinking of my old high-school friend with the similarly sounding name Pia, who might have dropped in on her way home.

‘No,’ she repeated. ‘Hang on,’ she said, ‘I’m the mother and you’re the daughter here, right?’

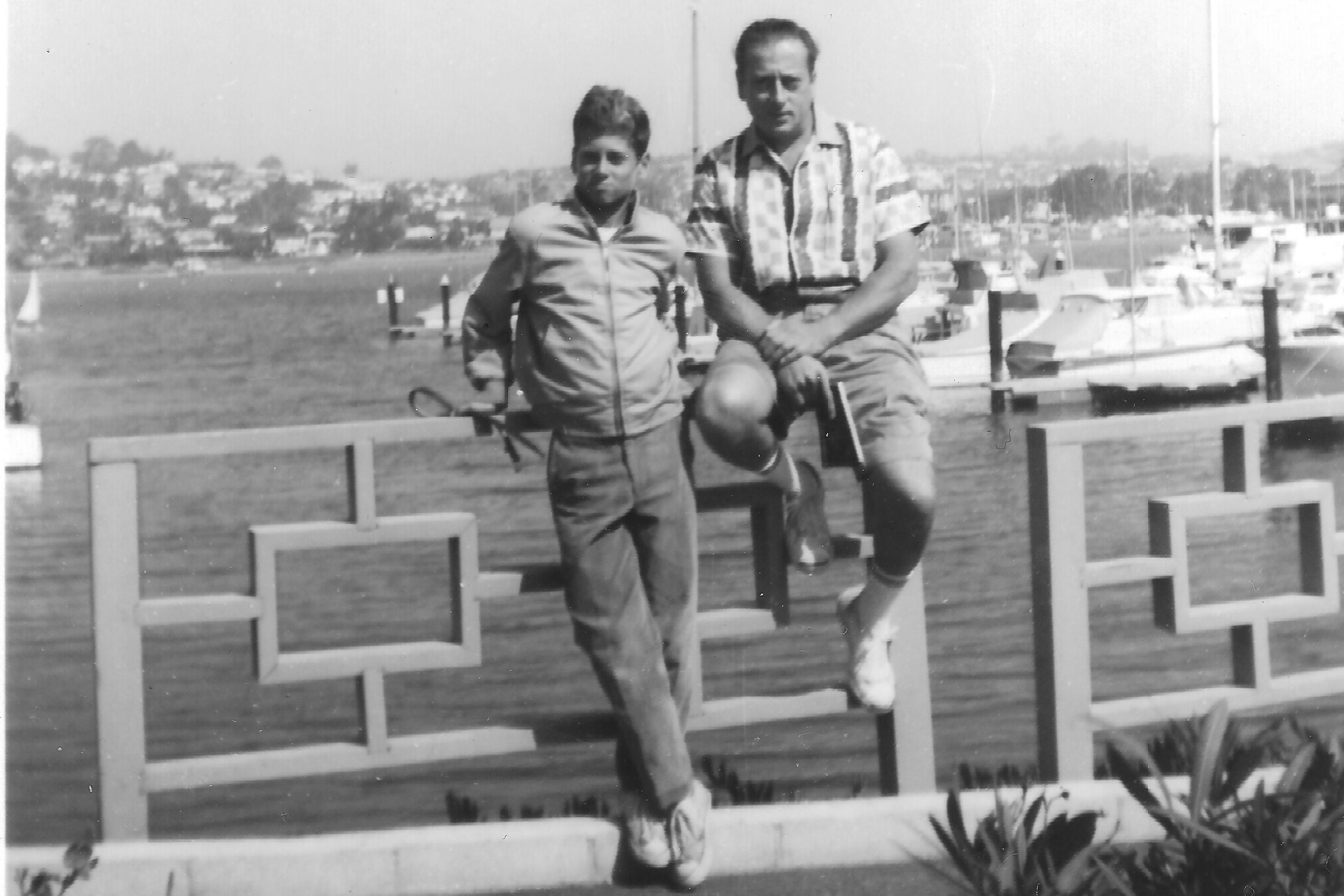

It had been coming for a while. My father had died two years before. The symbiosis they had achieved after almost 60 years of living together made the period after one of grieving and loss, sleeplessness and forgetfulness. But that night things took a different turn.

‘As long as it’s not me next,’ she said as we hung up.

My father’s father talked to everyone, including the figurines on the sideboard, and he sometimes saw the ships he’d worked on as chief engineer sail across the field behind our neighbour’s house. My mother’s mother stopped speaking, also to her husband, who she kicked out of their bedroom one night because she no longer recognised him. My well-mannered aunt suddenly started cursing with gusto when she thought people had stolen her jewellery, and came home from the daycare centre with her bag full of spoons.

That people could start losing their marbles, as my mother put it, is something I grew up with. So when my mother called thinking I’d just left her house with ‘Ina’, even though I was more than 300 km away and, actually, there’s only one Ina (me), neither she nor I panicked.

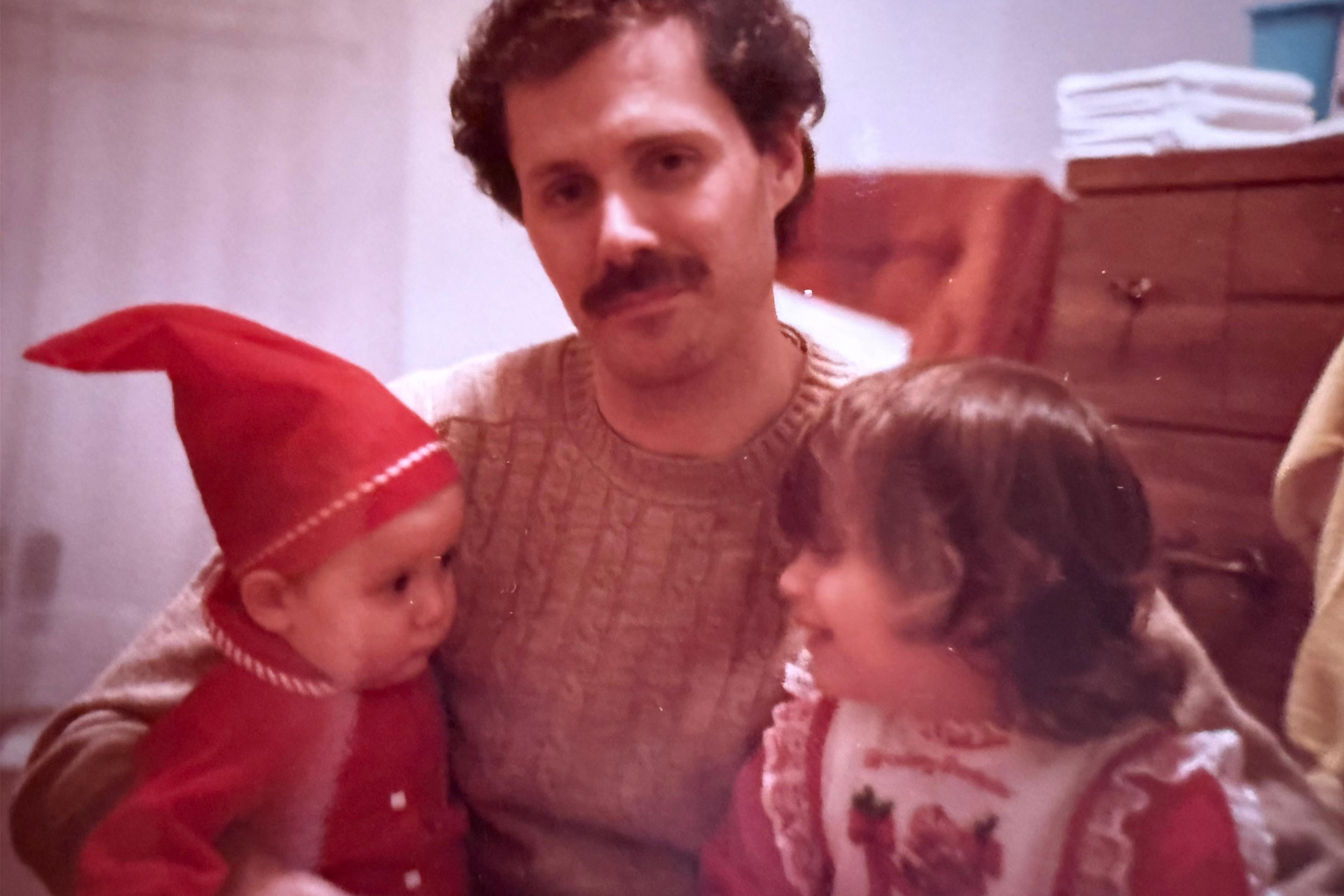

We went to see the doctor, and in March 2014 she was diagnosed with Lewy body dementia, a condition related to Parkinson’s disease but with hallucinations. And over the years to come, my mother’s home and our life together became populated by resurrected members of the family, including my father, my mother’s parents and sisters, and infants – especially boys.

As a young couple, my parents had lost two sons: my older and my younger brother. They were both perfectly healthy babies for six months, then started to waste away and died unaccountably before they were 10 months old. The doctors were at a loss, one of them accusing my mother of neglect. Back in the village, people didn’t talk about that kind of thing, and hardly anybody asked.

Since then, she’d been resistant to outside help, and didn’t welcome the homecare services now entering her home. My assistance she was able to swallow by appointing me her secretary.

How was all this to be understood? I knew the headlines of my mother’s life, but most of what I’ve just written I didn’t know offhand. Whereas my outgoing father had been easier to identify through his profession and community tasks, my mother had been more withdrawn and, to me, mostly just ‘mum’. But now, observing the meals she prepared for people only she could see, and her sudden appearances in flashy 1980s outfits, I needed to work out her whole story.

At first, I couldn’t help clinging to our old common reality, and began by killing my father every time she cooked for him.

‘Do you know something I don’t? Is your dad eating at some other woman’s table?’ she asked.

‘Well,’ I said, defending him, ‘he can’t come, because he’s dead.’

But the more time that passed since his death, the more present he became for my mother. On his abandoned desk, the things she put there for him to repair started to pile up, next to notes about water leaking in through the chimney and a punctured bike in the shed. At the end of February 2015, there was a birthday card on the day he would have been 83.

At one point, she started to see him in me, especially if I sat at his desk to sort out paperwork, just as he’d done when alive. She’d come and look over my shoulder, and ask when I was coming to bed.

And as I tracked along, she let me in on her rebel past. As a parent, she’d been stern, laying down the rules, but now I glimpsed her youthful defiance, hair down, biking barefoot in her grandfather’s castoff trousers. She’d been the third of four daughters to a father who kept aiming for a son to take over his builder’s business. When he wouldn’t fund the girls’ education, she moved to Copenhagen, working two jobs to attend high school.

The more stories we shared, the more roles I was assigned. One day, after I’d sorted out a money issue, she said: ‘I’m a lot of bother. Your kids shouldn’t cause you so much trouble.’ Then when she understood that she’d made me into her mother she said: ‘That daughter of yours is getting on a bit!’

We laughed, just as we did when I became her sister. One afternoon in the late summer, I arrived to find a beautifully decked table with Danish pastries, white wine and silver cups. My mother was elegantly dressed in pearls and lipstick, but someone was missing.

‘Our mother, where is she?’ she asked.

My grandmother, who would have been 111 at this point, was among the expected guests, along with my grandfather and two boys, who seemed to be the essence of all the boys she’d ever known, including my two sons and her own.

‘I live with the creatures that happen to be here,’ she said during one of our routine checks at the memory clinic. ‘My ghosts are friendly ghosts.’ There was obviously more at stake than physical changes to the brain. The need to gather all kin. The pleasure of welcoming them.

‘Does she still recognise you?’ people asked with concern.

Being recognised is one of the strongest threads in the web we spin to connect with each other, and in the beginning it bothered me that I was no longer clearly limited to being myself, but also had other family members in tow. Yet it didn’t become really difficult until the other ‘Ina’ started to lead an independent life of her own as ‘Little Ina’.

One afternoon on the phone, my mother asked me about company she was expecting that evening, people she called ‘the others’. How much food should she make? I said she should just make dinner for herself, because you never knew with ‘the others’. But she’d had enough of that kind of side-stepping.

‘I’ll ask Ina,’ she said, and suddenly I heard my own name resounding at the other end of the line as she yelled ‘I-i-na!’

‘Are you talking to me?’ I asked.

‘No,’ she said with love in her voice. ‘It’s my Ina, Little Ina.’

There was a brief silence. Then I heard my 57-year-old self say: ‘But I’m your Ina.’

‘Yes,’ she said, in a voice still infused with love, ‘you are, my firstborn.’

When I read through my logbook today, I trace a creeping jealousy in entry after entry during the year and a half when Little Ina made her presence increasingly felt. She was good with tools and repairing things. She could walk the dog on the beach all by herself. She was up to speed on the movements of ‘dad’, ‘the others’ and ‘the boys’. One autumn evening in 2015, I even saw her name written in red marker pen above a towel hook in my mother’s private bathroom, a place no one other than my mother ever entered without permission.

Later that evening I’d had to give up on fixing my mother’s old clock radio, its controls stiff with age. Annoyed, she said that Little Ina would never have quit. Equally annoyed, I said that I was Ina, but then I softened, saying I knew she also had her Little Ina who could fix anything.

‘Ina’s just what I call her,’ my mother said.

‘Have you ever seen her?’ I asked.

‘It’s more like a feeling,’ she replied.

It was at that moment, when first one of us and then the other shifted position, that we reached a new place together where something else could happen. In the time that came after, my mother started to talk about the years when her boys died. I’d asked her about it as a child, then as a teen, but it made her so sad that I had stopped. Now she talked openly about being paralysed by the senselessness of it all, about the people who didn’t dare to visit and didn’t know what to say. Plus the vigilance that she and my father had exercised over, and demanded from, the one who didn’t die – me.

‘When we were kids, me and my sisters had much more freedom than you ever had,’ she said. We said cheers to that.

The cancer she’d had before came back, and four years ago my mother died.

In hindsight, one of the biggest challenges for me was not so much her desperate attempts to keep track of the different worlds she inhabited, but more the subsiding of the secure and familiar image of myself she’d mirrored back for 58 years. It was one thing being me plus my father, plus my grandmother, plus my aunts. But ever-resourceful Little Ina, who took centre stage and could do – and was allowed to do – everything was something else completely. Was she an improved model of me? And who did that make me then?

One of many gloomy statements made about dementia is that it robs us of our loved ones while they’re with us, putting our understanding of them at risk. However, what really happens is something else: when we lose the familiar mirror image of ourselves we used to rely on, we end up having our self-understanding put at risk.

But seize the challenge! From the day we’re born, we’re formed by the opposition and support of others, and by the ongoing stories we share. It’s no different for someone with dementia, except that, as a daughter, I had to up my share of the relationship, so that the stories about ‘dad’, ‘the others’, ‘the boys’ and the life we shared could turn into a new kind of joint storytelling.

At last I got to know my mother as something other than just my mum, and saw the contours of the strong-willed, vibrant and incisive person she might have let out if she hadn’t experienced so much personal tragedy so early in life.

Translated from the Danish by Jane Rowley.