My mother kept them – her two favourite childhood dresses – first, in case she had a daughter; then, in case I did. Both were pale-blue cotton, with tiny graph-paper-sized checks, cup-like sleeves and flowing knee-length skirts. One, with a Peter Pan collar and a proud display of smocking on the front, was made by my grandmother, but the one my mum liked best was shop-bought, with bright flowers embroidered round the hem. She remembers wearing it when she was old enough to put on socks and shoes but, to her frustration, not yet allowed to go to school.

Her elder sister despised dresses so my mother feigned indifference, but my grandmother must have known it was an act. When they no longer fit, she didn’t pass them on to relatives, or friends, or charity; she put them somewhere safe. Later, after her younger daughter left home, she gave them back.

When I was born, my mother made a third dress in the same size: white with pastel posies, multi-coloured smocking on the front, pink buttons on the back. I can’t remember loving, or even wearing, any of the three – but I’m assured I did. I even left my mark on one, a tear. When I saw them as an adult, a less pragmatic, more nostalgic self, I thought them sweet. Perhaps I’d have a daughter. Perhaps one day, she’d wear them too.

The author’s mother circa 1958, visiting her grandparents in Adelaide.

Our first child was a boy. Curious blue eyes peered from a delicate round face, with hair that would darken, curl, and go rogue in his teens. I couldn’t see myself in him, I couldn’t really see his dad; he seemed a wholly new creation, wholly himself. We watched him in wonder, daunted and delighted to have this precious person entrusted to our care. We knew we’d teach him a thing or two about the world, but were unprepared for how hungry he would be to learn and understand, how much he would teach us.

Perhaps I also wished, some day, to be the mother to a daughter that my mother was to me

Our second child had dark eyes like my husband and a cowlick that defied gravity. He was wondrous in his newness too. I felt a twinge of disappointment but remembered we were open to a third: a girl was still a possibility. A girl who would climb trees with her brothers, who would wrestle and draw and dance with them, who would give those sweet smocked dresses further life and further rips, who would grow up, yes, move out, yes, travel, yes, one day have a family of her own, yes, but would always want and welcome her mum’s advice, help, company, love.

This is how things were – and are – between me and my mum. She is warm, dependable and wise. You could take her calm for granted, and I did. You could grow up forgetting that you’d lost your dad aged five; that single-parenting three kids for 14 years – then step-parenting three more – was not her plan. Some mothers expect to be in on every secret, in the room when you give birth – mine gave us space. She had other people in her life, other ways to spend her time, but she was always there when needed. Still she brings us food, still we return the containers that she’ll likely fill again; still she takes me to the airport when I have an early flight. When friends complain about their mothers, I fall quiet. I wish everyone could have a mum like mine. Perhaps I also wished, some day, to be the mother to a daughter that my mother was to me.

She was still a possibility, that little girl, when we decided we could manage ‘just one more’, a ‘third and last’. She remained a possibility when her elder brother was five and her other brother was three and I was pregnant once again, battling nausea and fatigue, and when a craving for pureed cauliflower replaced my usual love of coffee and chocolate. She was still a possibility when we told the ultrasound technician we didn’t want to know our baby’s sex, when we put an other-worldly sonograph on the kitchen fridge.

This labour was unlike the previous two. This time we knew the drill, that these things take time. I drove to a local café and, between contractions, bought a burger. My husband and I played Scrabble, and I won. Then came the realisation that we had taken too much time: the flight was boarding, my name was being called and I was nowhere near the gate. Very soon after we made it to the hospital, our third baby, our last, was born. Where his brothers’ brows curved quietly and predictably, his betrayed new mischief, flicking up at each end.

Grief over the closing of a door, he said, was understandable

I loved him utterly, unconditionally. And I still wanted a girl too. I lay confused and exhausted, feeling shallow and ungrateful and ashamed. How could three children fail to satisfy, when many long for one in vain? When we returned home – from a bed with a remote control, stiff with starch, to familiar, unwashed sheets – I confessed to my husband, and cried. A future I had hoped for would never come to pass.

My husband listened to me, held me lovingly. Grief over the closing of a door, he said, was understandable. His kindness gave me comfort. Nursing our baby, watching the older boys tumble round the bed and round the house, puffing, panting, falling in my arms, did too. But the unwelcome feeling lingered, like a question, still begging an answer.

I told my mother, and a beloved friend. Maybe I wanted to be judged, but all three confidants refused. When I tried to articulate my disappointment, it made less sense instead of more. I didn’t want a girl whose hair I could style, whose nails I could paint. I didn’t have visions of buying dolls when she was little and make-up when she was older. I hadn’t been that kind of girl; I wasn’t pining for that kind of girl.

In fact, I loved having boys. They were affectionate and earnest, messy and curious and hilarious. I savoured their boyhood because I knew they’d grow more independent, and likely more distant, as they grew up. But that would also be the case if they were girls – and, here, it dawned on me. What I wanted wasn’t contingent on, or about, sex or gender. It wasn’t someone to put in those old dresses; it was the closeness I have with my mum, which I assumed boys would grow out of while a daughter would not. It was the closeness I never had with my dad because it wasn’t possible.

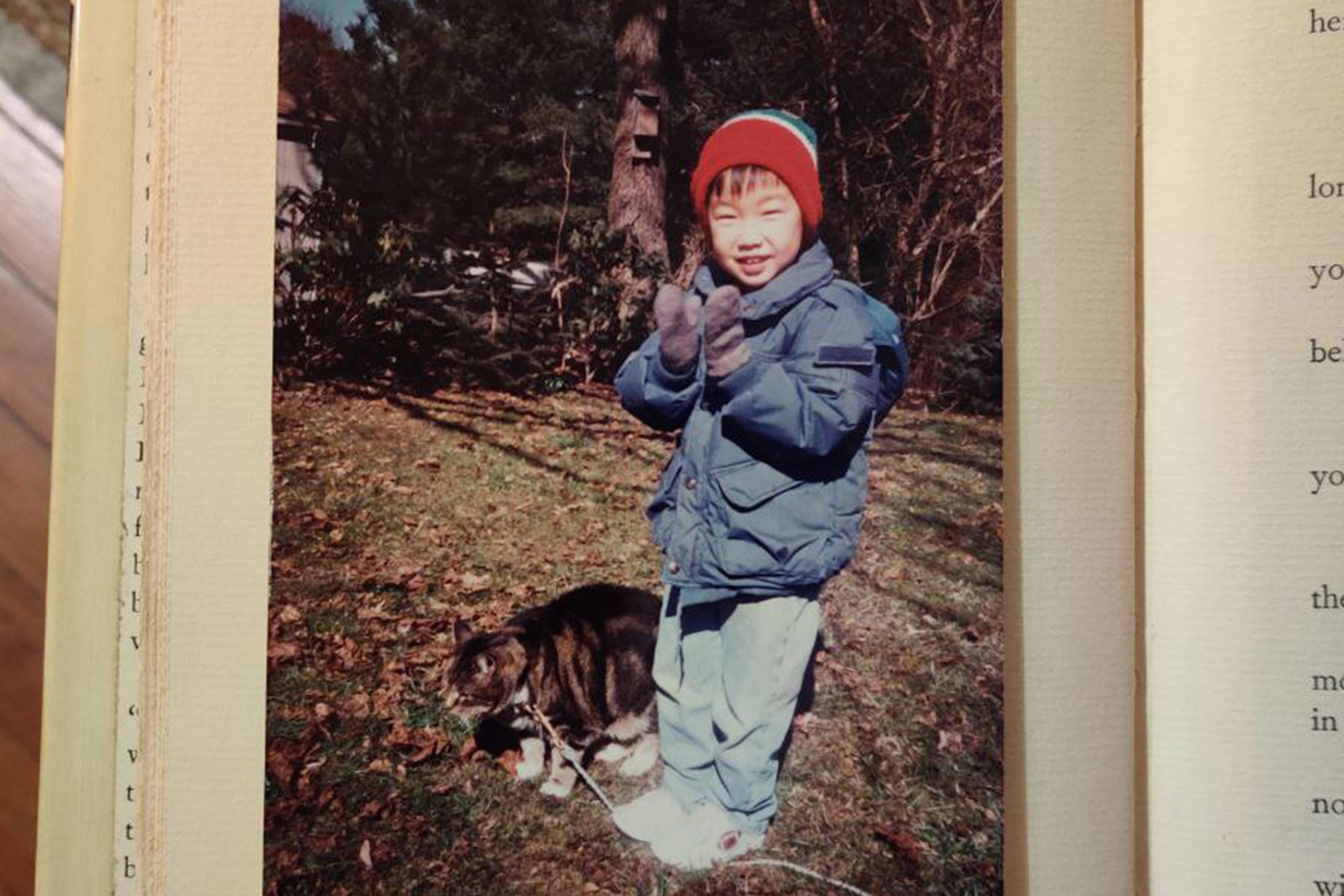

The author and her father.

Perhaps if brain cancer hadn’t taken him so early in my life – if he was still around when I was 10, 15, 20 – perhaps if my mother and I didn’t get along so beautifully, perhaps if she didn’t have to cover for him all that time, I’d have pictured different possibilities. With that realisation, the story I had been telling myself – the fiction of lasting closeness versus inevitable distance, daughters versus sons – collapsed. The disappointment disappeared.

Now, when I’m in the kitchen with our eldest, folding dumplings while we listen to a podcast – him with the right earbud, me with the left; now, when driving with our middle child, discussing or dissecting a story or a song; now, when our youngest, who loves to organise, rushes me out the door – I have no trouble believing I could have a relationship that transcends boyhood with any one, with every one, of them. And when our differences provoke admiration, fascination and humour, as they do with my husband – my partner who can hear the words ‘never mind’ without saying ‘tell me anyway’, who takes me seriously, but makes me laugh, who considers how things work, not just whether they work – I remember difference, too, can bind. What I wanted was a possibility I never lost.