In the beginning I was Black. That was all I knew. I was a little Black girl with a slightly older Black sister, living mainly with my Black grandparents in East Oakland, California, in the mid-1960s. It is true, or at least a likely sounding family myth, that the first thing my Black grandmother said upon seeing me was: ‘Oh good. If we do something about her hair, she can pass for white.’ But I didn’t know this then, any more than I understood that I lived within a Black culture. I just knew that the way my grandparents and cousins and neighbours looked was the way most people looked, and how they talked and acted and ate was simply the way most people were.

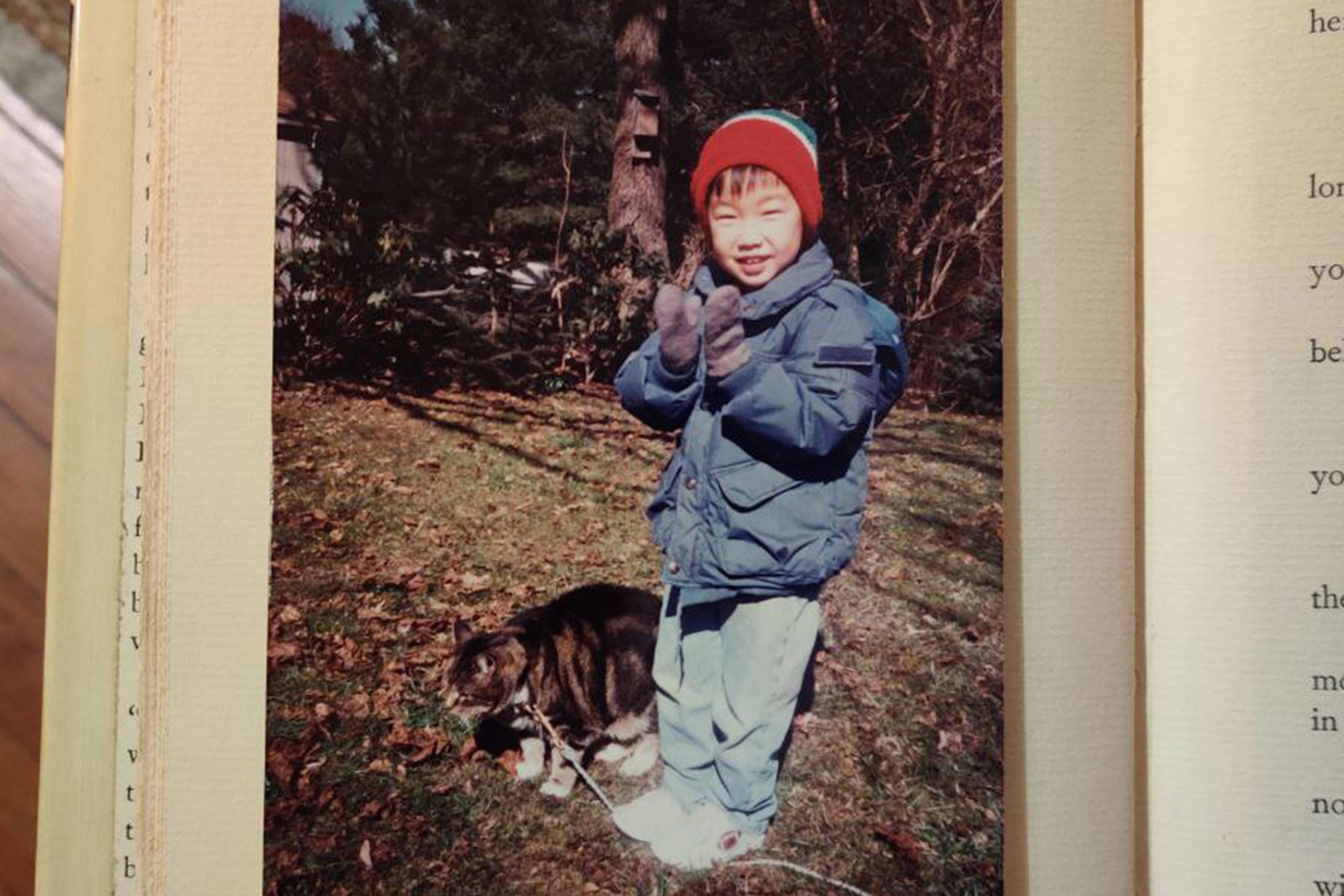

The author, at around age 3, in Grandma Swanigan’s house in Oakland, California.

In fact, because both of my grandparents were from the Deep South – Grandma a light-skinned Creole from New Orleans, Grandpa a very dark man from Mississippi – my life for those first few years had an almost stereotypical quality, the kind of Black family life I later saw in movies like Song of the South (1946) and Sounder (1972). We ate hominy grits and Aunt Jemima pancakes for breakfast, fried chicken and collard greens for lunch, jambalaya for dinner, Jell-O pudding for dessert. Grandma sang us to sleep with old Negro spirituals: ‘All My Trials’, ‘Come by Here, My Lord’. And, of course, she ‘did something about’ our hair every day, putting it in large rollers so that it curled instead of frizzing.

My mother – blonde, thin, Grace Kelly beautiful – hardly appears in those earliest memories. I now know she worked long hours to support us, as our father absented himself early on from our lives. My racist white grandparents, Mom’s Midwestern adoptive parents, were absent too: they had disowned and disinherited her when she married and had children with a Black man – something punishable by 10 years in prison in their state until just seven years before my sister was born.

What did I know about white people during these formative years? Consciously, nothing, though I must have absorbed the airborne messages circulating through all Black American households and neighbourhoods. By age three, when my mother and Grandma had some kind of falling out and Mom took us to live in mostly white nearby Berkeley, I already knew one thing for certain: I was not white.

Suddenly, the people looked different. The food and the music were different. Most of all, I was different – and not in a good way. My hair marked me as wrong from the start. (Oh, prescient grandma!) Mom kept the wild bush of it contained in tight braids. That hairstyle was the standard for little Black girls, but starkly different from the straight bangs and free-flowing locks of my white peers.

It was the start of my life as an alien. The kids in preschool looked at me sideways and shunned me; I played alone on the jungle gym and sat in a bubble of isolation on the floor during story time. Nobody wanted to be my friend. The white kids who were our new neighbours didn’t want to play with me, either.

Because I understood, even at that age, that my Blackness was the main source of my difference and the cause of my social rejection, my life in white society paradoxically reinforced my identity as a Black person, instead of eroding it. This may be why I didn’t find it at all surprising when, on being whisked off to British Columbia in Canada, at the age of five, I was not only shunned by the kids in the all-white rural community where we eventually settled, but subjected to outright racial persecution.

They swarmed me on their bikes while jeering the n-word

The bullies along our lonely back road and in my schools called me the n-word while pushing me into puddles. They stage-whispered the n-word behind my back while we were waiting for the school bus. They swarmed me on their bikes while jeering the n-word. On one occasion, a group of Mean Girl types amused themselves, with many sly sideways glances at me, by telling particularly nasty jokes. (‘How do you kill a n*****? Hang him out the car window till his lips suffocate him.’)

How they knew to use that particular slur, I can only guess. Maybe it was my hair. Maybe some of their parents figured it out and told them. Maybe they just had the bully’s keen sense of social smell.

Looking back, the fact that I lived a life of American-style racial persecution in a white Canadian valley may not be so strange. If a ghetto is just a malevolent form of what academics call a ‘knowable community’, the intimacy of a rural area makes it ripe for becoming one. It’s fair to say that the isolated, mountainous region where I spent most of my later childhood and adolescence manifested its ghetto potential as if it had just been waiting to be asked.

With my light skin and small features, I was viewed as a vaguely off-white person with problem hair

But if the kids who terrorised me were acting more out of racialised yahooism than the conscious anti-Black racism that I might have experienced in the US, I was in no position to appreciate the difference. Just as if I were still in inner-city America, my character warped around the armature of defensive Blackness. During eight long years of checking the road for bullies every time I left our property, urging my horse across the ditch into the brush when I saw them coming, and scrambling up the sandbank to dodge the clods of clay they hurled from the road, I developed a deep fear of white people. To this day, my body tenses and adrenaline surges whenever I interview for jobs, walk into a classroom, or even use a public laundromat.

Then, when I was 16, it all went away. Done early with school, I fled that place for Winnipeg, the farthest away I could get on my small fund of babysitting money. In the anonymising, indifferent Canadian city, everything that made sense of me blinked out. With my light skin and small features, I was viewed as a vaguely off-white person with problem hair.

This has been my predicament ever since. The way I look doesn’t match either the racial identity I started out with or the experiences I had because of it. So people can’t account for the way I am afraid, apart, reactive, struggling to gain the confidence I need to move out of poverty.

This inexplicability affects my life in real ways, especially my work life, where these traits are noticed and assessed but not understood or given the latitude that they might be if I were more visibly Black. For instance, when I got my first job teaching college English, some students every semester would refer to me as ‘intimidating’ on my evaluations. ‘Do you have to be so fierce?’ one of my deans asked.

How was I to tell them that I was much more afraid of them than they were of me – that being in a classroom with white teens and young adults sent me out of body with fear, that I hardly knew what I was saying, that the trembling in my legs didn’t stop for hours after I got home?

The most painful part of my status as an invisible minority may be that I am now lumped in with the group that persecuted me

Even in situations where I’m not afraid, my outlook and life experiences are often so profoundly different from those of my white peers that I get labelled ‘negative’ or ‘too intense’ – judgments that might be softened if people could see by my appearance where these traits might come from. During the daily storytelling ‘huddles’ at a recent job as an on-staff book editor, I ended up coming across as a Debbie Downer to an almost laughable extent. My well-groomed white coworkers told stories about childhoods that to me seemed almost fictitiously carefree – happy trick-or-treat outings, sleepovers with their besties, fun school trips. I could only respond to the prompts with mumbled tales of Hallowe’ens spent cowering at home while the local hooligans slashed our tyres and put burning trees across the road near our house, or school outings where the best thing that happened was that everyone totally ignored me. Needless to say, these huddles failed to integrate me into the team.

The most painful part of my status as an invisible minority may be that I am now lumped in with the group that persecuted me. To Indigenous people, I am one of the colonisers. To people of other minority races and ethnicities, I am part of the white majority, with the experiences, alliances and privileges assumed to come with that.

It would do me no good to say that I am half-Black and grew up within an African American experience. Such statements would meet with an inescapable logic: if people need to be told, it’s because they can’t tell; and if they can’t tell, then I couldn’t really have lived the experiences and suffered the disadvantages that go with that identity. I know I’ve paid the price of the ticket, but everyone else would think it’s stolen.

I’ve lived with this case of mistaken identity long enough to know that there’s no real solution. I could move back to the US, but I can’t afford to live in a country without free health care. I could straighten my hair and deliberately pass for white – except, really, I couldn’t. I wouldn’t have the first idea how to: sooner dip a zebra in orange dye and ask it to pass for a tiger.

We want to be who we are. We would just like to lose less for being it.

I ease my chronic ache with the knowledge that I am not alone in my misread identity. I know, for instance, that many First Nations people who ‘don’t look Indian’ share this pain. So do my friends with complicated identities, including an African of Indian descent who grew up in white rural Canada, and a man of Chinese and white parentage who is usually taken as either one or the other, but not both – and he never knows which one.

We joke about getting forehead tattoos proclaiming our racial identities, or creating pamphlet biographies as required prereading for anyone new in our lives. We speak with wistful envy about people who are famous enough to put out a fuller and more complicated version of their identities than the one that is immediately apparent.

But, really, I know my situation is nobody’s fault. We’re a visual species, and we live our public lives as the race other people see, not what we know to be the case. All I can do is stay honest about both the pain and the rewards of my complicated identity, and work on healing from the past.