It is not nearly so far a journey as you’d expect between flying and frying. At 10, my father sent me down to the small youth club at the bottom of the hill behind our house in London to study judo. Our dojo master Tom must have been in his 50s – ancient – a wiry, compact man with deep bags pooled under his eyes and a spray of salt in his floppy thin mane. A younger blade ran the classes – an orange belt to Tom’s black – and at least once I remember Tom saying: ‘This is it – youth versus smarts,’ as they grappled each other. After a few swift kicks this way and that, attempting to dislodge each other from their footing on the canvas, Tom got a hold of the young man’s cotton lapel and he went flying.

I went flying rather more frequently than that blade and would comfort myself around 10 at night, after my family had long since dined, by sloping off to the Wimpy Bar. Even if it had been day, the worker’s café was too noisy and impersonal for a child, the proper Indian or even Italian restaurants too posh, too full of rich jewellers or lawyers or even bank managers. Wimpy was safe. I always ordered the same thing. A burger and chips, then watched as it fried on the griddle amid its own onions. A sundae, its ice cream pulled from a nozzle, elegantly tapered off into grooved swirls. A banana was halved, nuts and chocolate syrup drizzled onto a long, canoe-shaped dish. The chef wore a white jacket, tighter than the judo one though perhaps more stained.

Decades later, I was hired to be the kosher supervisor of a university lunch bar to prevent exactly the sort of dietary combination of meat and milk I’d been devoted to as a child. If you’d asked me at 10 about the laws of kosher cuisine, I could not have told you; my parents were not religious. I absorbed those laws later, first while moving through a more observant milieu, and then more deeply as a rabbi – where the lowest rung, like the dans of the black belt, requires mastery of what is permitted and forbidden, including the laws of mixtures. The short version: you can’t cook a kid in its mother’s milk. From this verse, repeated three times in the Pentateuch, the rabbis deduce a whole world of dangers from combining meat and milk – from eating an ice cream sundae, say, right after a steaming, succulent burger.

At first, I supervised the non-Jewish cook whose previous job had been at a fish bar and who knew very little about Jewish kitchens. Then one morning she slipped on the ice on her doorstep and twisted her ankle, and the manager, a wiry student of around 20 named Kobi, asked me if I could cook. Two hours into my first day cooking, Kobi realised that the small kosher lunch counter serving maybe 30 students would limp along and get much nearer to breaking even if he paid only a cook-supervisor for three hours. The original cook, a single mum, never came back. She had been telling me about the presents she was planning to buy her son and, while I don’t mean to suggest I beat my breast in anguish, I have often wondered what became of her, the Christmas presents, the son.

People eat at McDonald’s today, and sit at benches that are tilted, just like bus stop benches are tilted to stop people getting too comfortable

My favourite dish to make for the students was a burger. A tray of beef mince, say half a kilo, not too lean: you can’t taste the beef if it has no fat. An onion finely chopped. Salt and pepper. An egg yolk worked into the mix. A scattering of breadcrumbs to bind and blunt the heaviness of the meat. The only thing I’d say made my burgers special was the chilli pepper I chopped into tiny pieces so that it couldn’t be seen and would mix in along with the onion that peeked pale and white out of my patties even after frying. Not one of the students who ate them could have told you why they liked my burgers or were willing to eat them twice a week. I’d say it wasn’t because they were strictly kosher or because I cooked them slowly on an open griddle just like at Wimpy’s. Rather it was because each bite you took had a little bite back of its own wrapped deep within it, and as you fly up through the air after some bruising or another, you like your comforts to tell it to you straight.

When Kobi’s time at the university came to an end, the university offered to start a full-time kosher café. I was asked how much I would charge to run this café full time, and suggested a possible figure. Then the national union of Jewish students closed the Hillel House canteen to give the university’s kosher café a chance to flourish. Only the university’s proposal never came to fruition. Suddenly it became an offer to buy in frozen ready-cooked meals from Manchester and sell them at a mark up, to be heated and served on the same tables as other students were having their non-kosher food. Even as an economic proposition, paying more for a frozen meal than they could have bought it for themselves made no sense to the students and that was the end of that.

And perhaps it was not needed, I hear you say. Perhaps. If they needed their lunch badly enough, they’d protest, I hear you say. But it’s not about the lunch. People eat at McDonald’s today, and sit at benches that are tilted, just like bus stop benches are tilted to stop people getting too comfortable, to not let you entertain the notion that you are anywhere like home, to get you off that bus stop-style bench and get somebody else there to buy another bun.

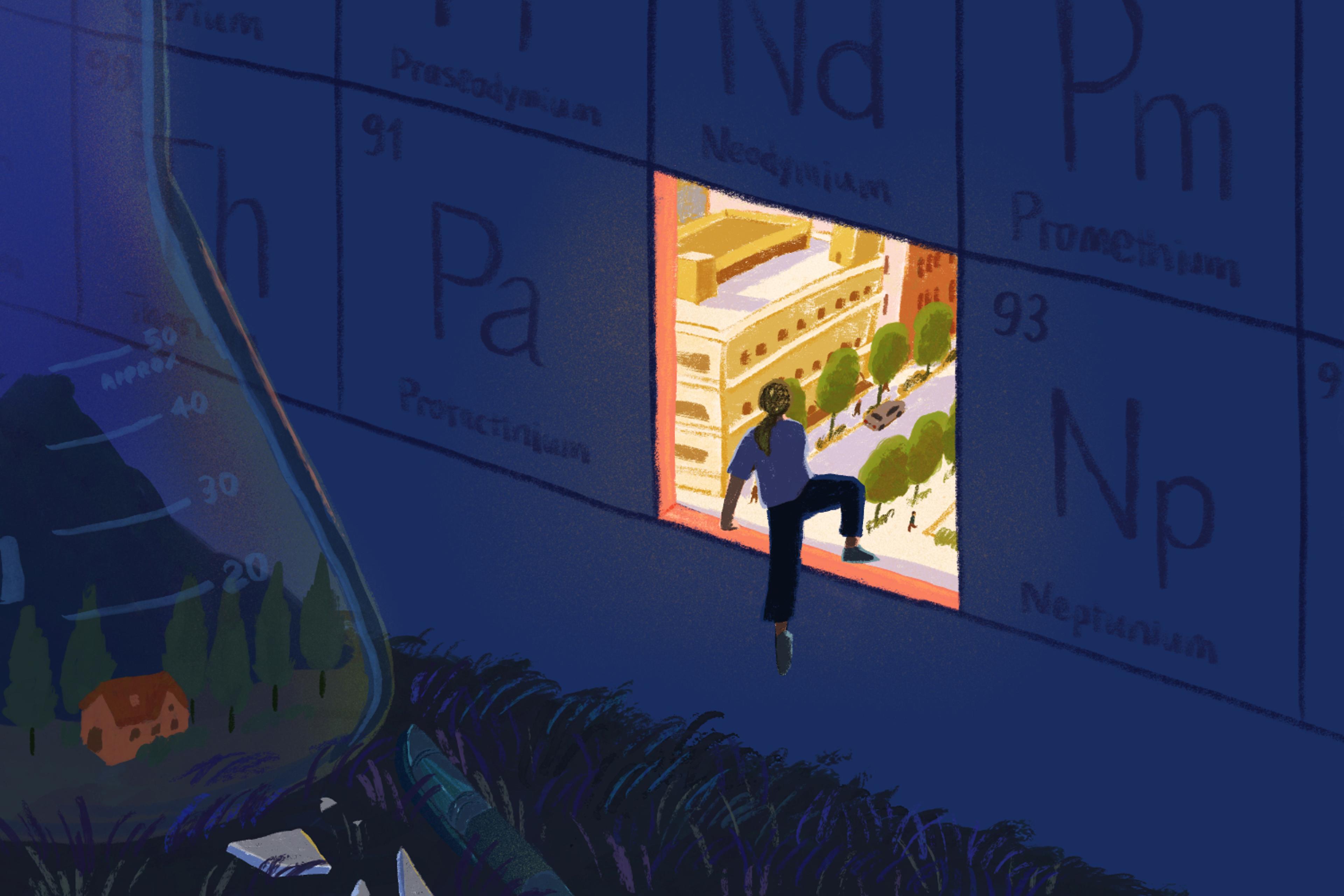

Wimpy Bar in the UK in the 1970s. Photo by Alamy

I used to run into former lunch-counter customers of mine around the university and ask them where they ate. They said they cooked for themselves or ate at communal events run by the Jewish chaplaincy or the rabbis. At those events, they were expected to listen to something, to profess a belief, to buy something, if you will. After I left that job, I worked in the public library in a suburb of Leeds. There were cafés that sold coffee but would not let you bring your own kosher food, there were benches on the street where you might stop but be disturbed. I used to take my sandwich into the graveyard because it was the only open space nearby with a bench where nobody would require me to buy anything.

What Wimpy and these tiny kosher businesses offered is not food or even care but space

Since that lunch counter closed, the only kosher establishment you can eat at daily in Leeds is a bakery on the grounds of one of the synagogues. What’s different about it is not the food, or even the kosher ingredients, but the attitude to space. The place itself allows maybe 10 people to sit comfortably inside but it’s the picnic tables outside on the paving stones leading to the gate that I’m talking about. The bakery began with two tables under an awning for the eight days of the year that observant Jews cannot eat bread indoors but have to sit in ‘booths’ to commemorate the Exodus from Egypt. Then the festival was over and the ‘booth’ got put away until next year, but the picnic tables stayed. Then the bakery added more.

The tables are there so you stay and talk. It’s possible you’ll go back and get more coffee, but nobody comes to ask you if you want anything else. The tables serve a social role in the community, one of the few places in Leeds where two older Jewish ladies can sit at a table over kosher food and compare notes about their grandchildren. What I learned cooking at the lunch counter was that what Wimpy and these tiny kosher businesses offered is not food or even care but space. I was, for a time, providing a space where people could feel cared for.

When my son comes out of his jiu-jitsu classes and eats his snack, he does it standing at a bus stop. I try to talk to him about his class but he does not want to talk at the bus stop. You have to sit down somewhere, a place between your home and where you do what you do, to really hear yourself. What I needed after going flying at the judo club was a space where I would not be hurried, nor cajoled into buying anything more, just a place to come to myself again. I do not know that those old ladies at the picnic tables go flying on judo mats, but life throws everybody a curve on a regular basis. If you don’t have that place to go to – how will you think about anything you want aside from the next bite?