Two decades ago, I spent the day with some retired Catholic sisters at a retirement home that rivalled Versailles. The grandeur wasn’t a surprise. Sisters who had worked in education often retired in little more than poverty. But the law required that healthcare sisters like these be paid a small salary. Since they declined the pay, the money went instead toward beautiful retirement convents with European architecture, opulent gardens and more.

I arrived at the Villa de Matel outside Houston bloated with education (an MD and a PhD). My project: comparing 21st-century hospitals, run by business executives, with their mid-20th-century century Catholic counterparts, where doctors, their spouses and the sisters once held sway. I saw bent, elderly women dressed in habits walking about, seemingly oblivious to the luxury around them. Their stooped postures and arthritic hands revealed the toll the years had taken – folding or washing or cleaning or sterilising, tending to the sick until the day they would lie forgotten in a graveyard on Church grounds.

Sister Lucille had been awaiting my visit. I expected a morose, severe expression, but instead found a stout, thickset woman, originally from Ireland, with a sweet, kind face, radiating both a merry outlook and businesslike courage. Indeed, in another life, she might have been a pastry chef. I interviewed her and several other sisters.

Then Sister Ruth walked in. In her mid-80s, wrinkled and nearly toothless, she nonetheless gave off the air of an uninhibited young woman. Her eyes sparkled matter of factly, and she spoke plain truths, often with a nice sharp barb attached to them.

She told me how she became a sister: she had passed a church in Shreveport in Louisiana, heard bells, and walked in out of curiosity. A nurse and a Baptist at the time, she asked a resident sister: ‘What do you do? Do you kneel? Do you pray?’

Afterward, she worried that she didn’t see Jesus.

‘He was there at the altar,’ the sister explained.

‘I asked her if I could go back and check, and she said yes,’ Sister Ruth told me. ‘I went back at three in the afternoon, and I looked all around the altar, above and below, and I couldn’t see him. Then all of a sudden, I felt him and I knew I had to become a Catholic.’

Three months later, she decided to become a sister herself. ‘The Mother Superior told me that I had to be a Catholic for three years before I could become a sister. I told her that I didn’t want to wait. She said: “I don’t know what we can do with you, but come back next Sunday and we’ll see.” So I went to services the next Sunday and they had singing above and below, and they gave me a book to read. I wasn’t sure what to do. I was afraid to look up, afraid to look down. Then, all of a sudden I heard something, the word “forever”, and they grabbed me and kissed me and I became a sister.’

Poor God sits on his throne, she said, a little sweat rolling down his back, unjustly accused

She believed in the restorative capacity of chicken soup, declaring: ‘I may not know how to split the atom [but] I had my own bag of tricks’ for cheering up patients. When that ‘broth boiled up in a cloud, what a sight! You just knew it was strong medicine.’ I pictured some anonymous patient from long ago, stretching his thin, scraggy neck over a bowl of soup, looking up, grinning, his good spirits affirming Sister Ruth’s conviction.

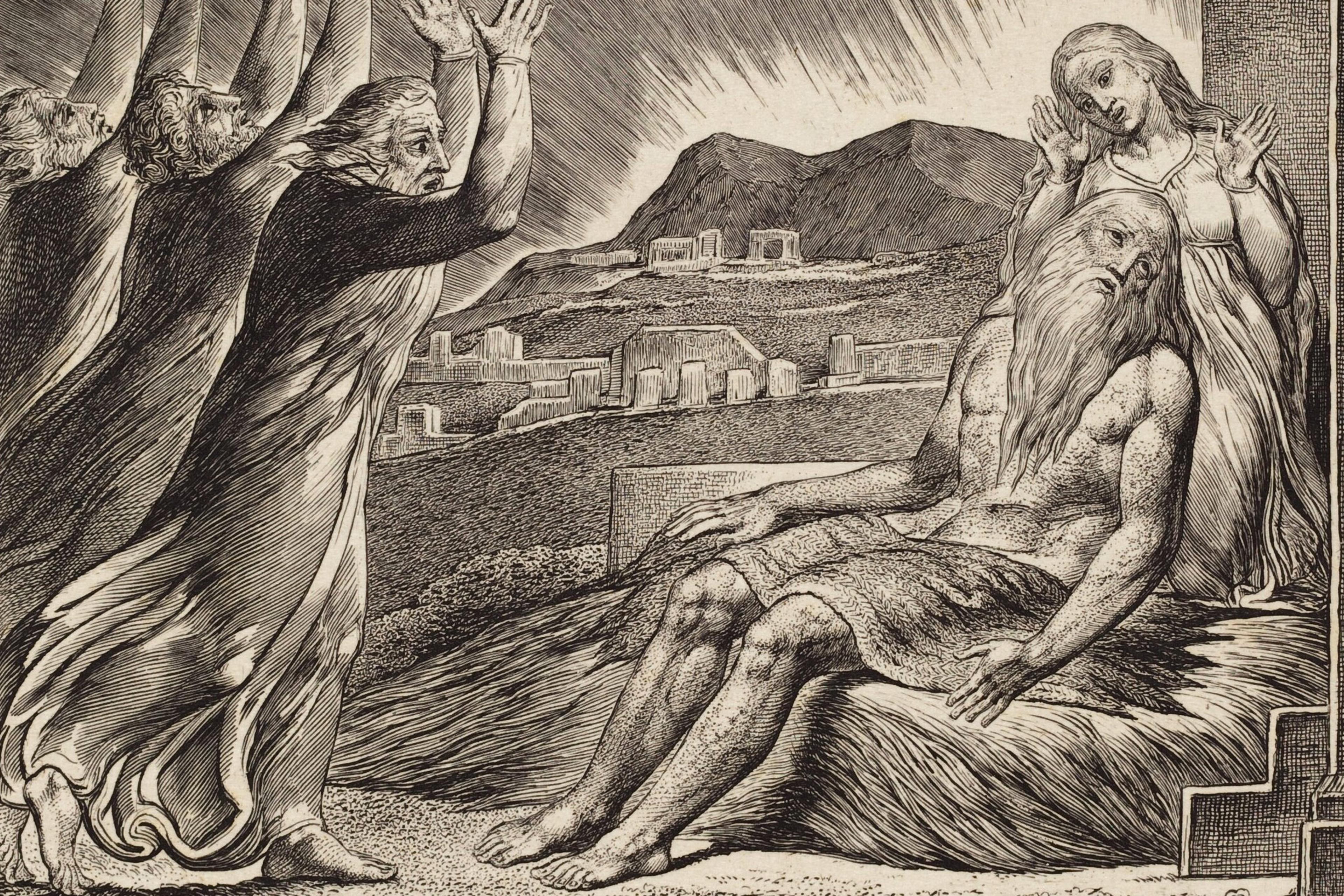

She told me how she had once rekindled the faith of a woman who was beginning to lose it after life had gone off-course. Imagine God as a general, busy before a battle, with a headache, trying to foresee all the things that might happen, she told the woman. The battle starts, but it turns out to be a flop. Why is it a flop? Don’t know. Could be a million reasons. But people blame God. They think they had nothing to do with it. They complain: ‘We built churches to you. We praised you in song. Now look what happened. Explain yourself!’ And poor God sits on his throne, she said, a little sweat rolling down his back, unjustly accused, because it was the people themselves who had made bad choices in the heat of battle, only they would rather blame God before taking any of the blame themselves.

As a description of how people tend to blame others for the bad choices they make, her vivid story fixed itself in my memory more than any official psychological explanation could. What was the basis of her knowledge? It was neither science nor art, but poised between them: dogmatic in its structure yet animated by the imagination; logical but also irrational. Any person could learn its rules, and yet there were people like Sister Ruth who were masters.

I studied her. Was she a ‘soil’ person, a full-blooded clod of clay, dressed in a sister’s habit? No. Although her knowledge was strange and murky, she was too smart to be just that. I looked more closely and saw something else – resolve. For all her wisecracking and readiness to see the humour in things, she was seized by a single passion in her youth, to become a sister, and she stayed true to it through old age.

I climbed into a golf cart with her and Sister Lucille to tour the property. They showed me a small hermit’s house where a sister lived when she wanted to go into isolation for a month. I saw the sisters’ cemetery. Then they took me out to dinner, where we were joined by a third sister not yet retired and still working in the community.

This third sister was a type immediately familiar to me. In her mid-40s, tall, well-nourished, college-educated and with an advanced degree in social work, she spoke in professional, polished phrases. She conceptualised. She name-dropped abstract theories. As a type, she was… me. Although kind and well-meaning, she was also pedantic, someone in whom the poetic dimension had been crusted over by learnedness. Compared with the other two sisters, she lacked juice and full-blooded sensuality; her language imparted an academic flavour to all that she said.

If Jesus was in me, I wouldn’t be screaming in pain. I’d want to sing and dance!

At dinner, she sat next to me, while Sister Ruth and Sister Lucille sat opposite. Sister Ruth held court: ‘It was hard getting used to that long habit, especially when I had to go to the bathroom. It was like wearing an evening dress. And our headpiece! First time I tried to put it on, I put a pin through my head. Couldn’t drive in it either. The DMV said it was dangerous. And you can’t eat a hamburger with it on. You can’t open your mouth wide enough to get it in. I haven’t had a hamburger since before I was a Catholic.’

From out of the corner of my eye, I saw the third sister stiffen, but Sister Ruth pressed on.

‘The first time I went to mass as a sister, the other sisters were chanting and their arms were folded… I thought they were in pain. And they said it was because Jesus was in them. And I told them, if Jesus was in me, I wouldn’t be screaming in pain. I’d want to sing and dance!’

That dinner table was the great divide, the two sides symbolising two antagonistic eras, two outlooks on the question of how to inspire another soul. On my side, the third sister looked upon Sister Ruth and Sister Lucille as if they belonged to a more primitive age. She was the embodiment of the new, the coming time, the professional sister, the expert sister trained in modern therapeutic technique – often living outside the convent, commuting to work, and, in some cases, no longer wearing the habit at all. Sister Ruth and Sister Lucille symbolised all that was dying out – the lay sisters, the romantics who conquered human misery not with science but with legend, mystery and presence; in Sister Ruth’s case, with a sublime uncouthness as well.

It pained me to be on the third sister’s side of the table. I wondered: if my heart ached, who would I want to console me? Who could speak words that touched the deepest parts of me, to quiet the agitation or soften the pain?

In time of distress, God spare me the professional language without shading or flourish

I sensed that Sister Ruth and Sister Lucille were slightly embarrassed by their relative lack of education. Had they arranged for this third sister to join us to compensate for their perceived deficit, as a kind of apology to me?

I wanted to shout out: ‘No! I am with you, Sister Ruth!’

Up to that time in my academic life, I had aimed my critique mostly at the overprescription of antidepressants for everyday unhappiness. I’d hardly considered the rise of therapy, structured like fake friendship and turned into technique, now crowding out the intuitive, deeply human care that people once sought. The number of psychologists, social workers and therapists in the US had increased by orders of magnitude since the 1940s, although the population had only doubled. Why, I wondered, when art and religion (in Sister Ruth’s case, they were the same thing) could clear the clouds and raise spirits more?

In time of distress, God spare me the objective person, I thought during that dinner. Spare me the professional language without shading or flourish. Spare me the clear, correct and certain phrases as unimaginative as a report. Give me words of folly and words of profound significance. Give me someone who dwells on the old riddles, even if she makes nothing of them. Give me Sister Ruth.