I had promised God 5,000 Kenyan shillings if I got a good job. Back then, I was an underpaid and overworked casual server; a year later, I became head waiter at a bush lodge near Lake Nakuru National Park. Life had turned around for me in an excellent way and then I remembered, guiltily, that I had not kept my word. So, I requested time off work to go down to my church in Nairobi, four hours away.

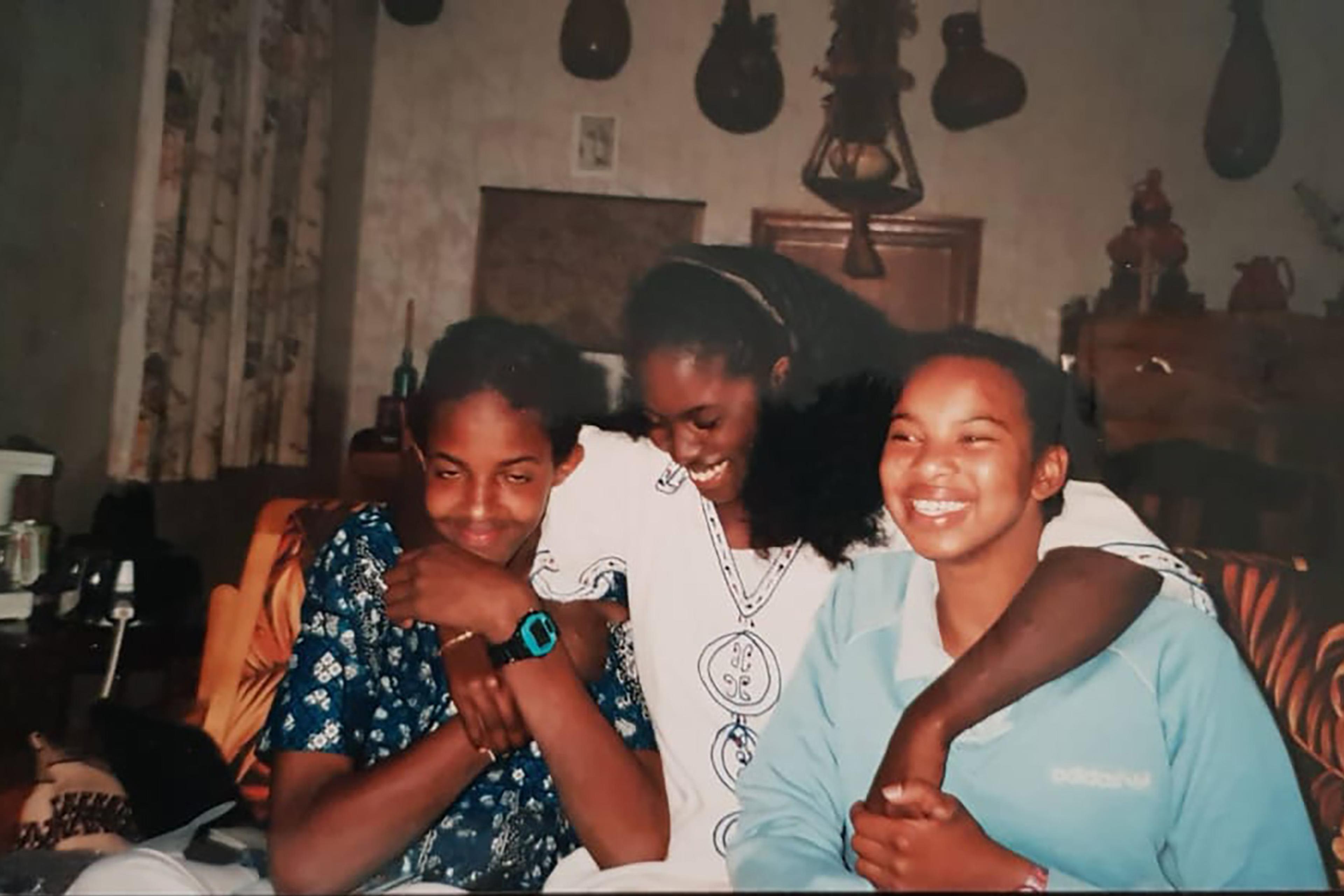

I took an old friend with me: Steve, tall and brown, and good at math. He was the first boy I’d truly had a crush on: so that we could spend time together, I’d ask him for help with homework but we usually ended up playing games or discussing his girl problems. He always got an A. I never did. I hadn’t seen him since college; the bus ride, I thought, would be a good chance to catch up. Indeed, the time flew by.

As the bus neared Nairobi, it being the end of the month, I decided to check my bank app to see if my salary had been deposited. Instead of my usual balance, a random long number stared back at me.

In my confusion, I showed my phone to Steve, who jumped in shock at how rich I apparently was. He must have thought I was showing off. Me, I’d never seen such a tremendous amount of money in my life.

‘Try transferring some to your M-Pesa [mobile money service],’ he advised.

I did, and to my surprise, the transaction was successful. I now had an extra 50,000 shillings (around $380) in my money transfer app and 1,450,000 shillings ($11,200) in my bank account.

It couldn’t possibly be because they didn’t want to acknowledge their benefactor being gay, could it?

We passed by my church and I gave the 5,000 I’d promised, wondering now if that amount was too small. Next, we went to the bank; I figured I needed to know whose money this was before spending it. It was transferred 10 days earlier, the statement said – no call, no text, no concerns raised by the bank in all that time. Perhaps I had a secret benefactor? The lodge where I worked received many white guests and a few had shown interest in me, enquired whether I thought of returning to school. (I was 21, had taken leave due to fee challenges.) Maybe one of them had decided to send me some money? The only wrinkle: I’d never shared bank details with any of them.

Still confused but allowing myself to be excited, looking for its rightful recipient – but not hard enough lest I found them – I started spending the money. First, I tithed 150,000 shillings to the church, attaching a letter to the bank receipt that explained I didn’t know where the money came from, also that I am gay and would appreciate prayers and guidance. I included my email but the church never wrote back – perhaps because of the dubious source of the money, although they never returned it either; it couldn’t possibly be because they didn’t want to acknowledge their benefactor being gay, could it? Then, I bought a Mazda for 600,000 shillings, thinking I’d lease it as a taxi.

Two months and 850,000 shillings later, the jig was finally up. I’d decided to go back to college and needed to withdraw another 100,000 to rent and furnish a house nearby. At the bank, the teller paused.

‘Are you sure you don’t want to use the ATM?’ she asked.

‘It has a limit of 40,000,’ I reminded her. She told me to wait and disappeared into a room.

Twenty minutes later, suspecting something was amiss, I tried to leave. But the exit was locked, the guard insisting I wait for the teller to return. I braced myself.

Hungry and lonely, I curled myself into a corner but the cold from the walls seemed to seep into me

Outside, Steve was waiting for me in the car that was to be a taxi. When I didn’t return, he came in and found me flanked by four men from the fraud unit. They put us both in the boot of an SUV and drove us to a building where three officers interrogated us: the first civil and calm, the second a lady who chimed in occasionally, and a very short and violent man. Nothing I said made sense to them – I had received the money from nowhere, I said, I was no scam artist – but even I could tell I was sounding like a liar who ran out of lies. Truth be told, I was hoping they would have answers for me.

They let Steve go but took me to a local precinct for the night. My cellmate was a boda-boda rider in a heavy leather jacket and pants that he held up with his hands, since the officers had taken our belts and one shoe each. He told me how sad he was for me, so young and so cold – our conversation withered after that. It was raining outside and inside there were no mattresses, no blankets. The cell had two tiny windows very high up, with three metallic bars each and no other covering. Hungry and lonely, I curled myself into a corner but the cold from the walls seemed to seep into me. For the first time in my life, I wished for death to save me.

I must have dozed off because what I remember next is the bang of the door and an officer shouting. Back at the fraud unit, after a cup of tea and two mandazi, I was made to stand for multiple mugshots, then taken to Milimani Law Courts – a very attractive building from the outside, built in the classical style, nice inside too, I imagine, for those who get there differently. Later, I was taken directly to the holding cells in the basement: dark and dank and over capacity, perhaps deliberately to discourage repeat offenders. Everyone was shouting, often for no reason, especially the officers; asking a question felt like you were adding to your charge sheet.

After what felt like hours, my name was called, then I was in courtroom #6, then before a judge who asked if I was guilty or not (not guilty, I said), then reeled off the terms of bail: a cash bill of 200,000, or 1 million in collateral. For the next three days, I was on remand, waiting for my elder brother to sell off some of his possessions and come get me.

Something changed in me after that first night in the jail cell, after I shared a shower with 20 strangers, shuffled through the dungeon-like passages under the law courts, slept in the dirtiest room I’d ever set foot in. I realised how good my life had been: a clean bed, water to shower, personal space but most of all freedom, physical and mental. In remand, when anyone asked, I said yes, I am attracted to men. The one place I thought would be unsafe if people found out about my sexuality turned out to be the opposite. One of my cellmates, from Nigeria, warned me men would use me for rituals. But another, a short and masculine-looking 30-something, came out to me as bisexual.

I had never been in a relationship before, probably because deep down I still believed being gay was a sin

When the case went to trial, I was my own lawyer because that is all I could afford. The courtroom was cold and lonely, but I realised how scared I was only when I spoke, pulling my voice from my stomach. One day, I took Steve with me. On the way home, he told me my questions in court were irrelevant. But how would I know what was relevant? I asked whatever came to my mind: for instance, why did the investigator wait a month before contacting me, why did he need to lay out an elaborate trap when I had no prior history of fraud, or why, for that matter, did the accountant not report the erroneous transaction?

The case dragged on. In March 2020, a year after that money first entered my life, I went to Mombasa to make a delivery to my uncle Dan. Just then, the country entered COVID-19 lockdown and we both got stuck there. Around this time, I met a man named Evans on Facebook: after a month of talking online, we moved in together and he fed, clothed and took great care of me. I had never been in a relationship before, probably because I was green and deep down still believed being gay was a sin. Part of me stayed because, as good as Evans was to me, I also feared returning to Nairobi, having no work, no money, and the case hanging over my head. Due to the lockdown, I no longer had to present myself in court and, in the meantime, Evans and I started a small poultry business together in Mombasa.

By the time the magistrate pronounced me guilty a year later and sent me to remand for three weeks until she decided on the sentence, the business had matured enough to furnish the 50,000 shillings I now needed to make bail. As for the sentence, I was given a one-year probation: I was free, as long as I had regular check-ins with an officer. I decided to stay in Mombasa.

Meanwhile, my uncle also had a new boyfriend – Henzi, tall and Swahili, with the most beautiful smile I had ever seen – and, when he couldn’t go back to Nairobi, they too started a new business: making soaps. Soon, one of their regular clients, a programme officer at Pema Kenya, a community-based organisation for gender and sexual minorities, asked them to run a soapmaking workshop as part of their socioeconomic empowerment programme. Dan and Henzi jumped at this since it promised good money; meanwhile, I was busy with my Evans and frankly always felt too good to be near such organisations, considering them the source of most HIV infections in the queer world. But when Henzi had to drop out, Dan asked me to sub in; unable to resist the offer of 1,000 shillings a day, I said yes.

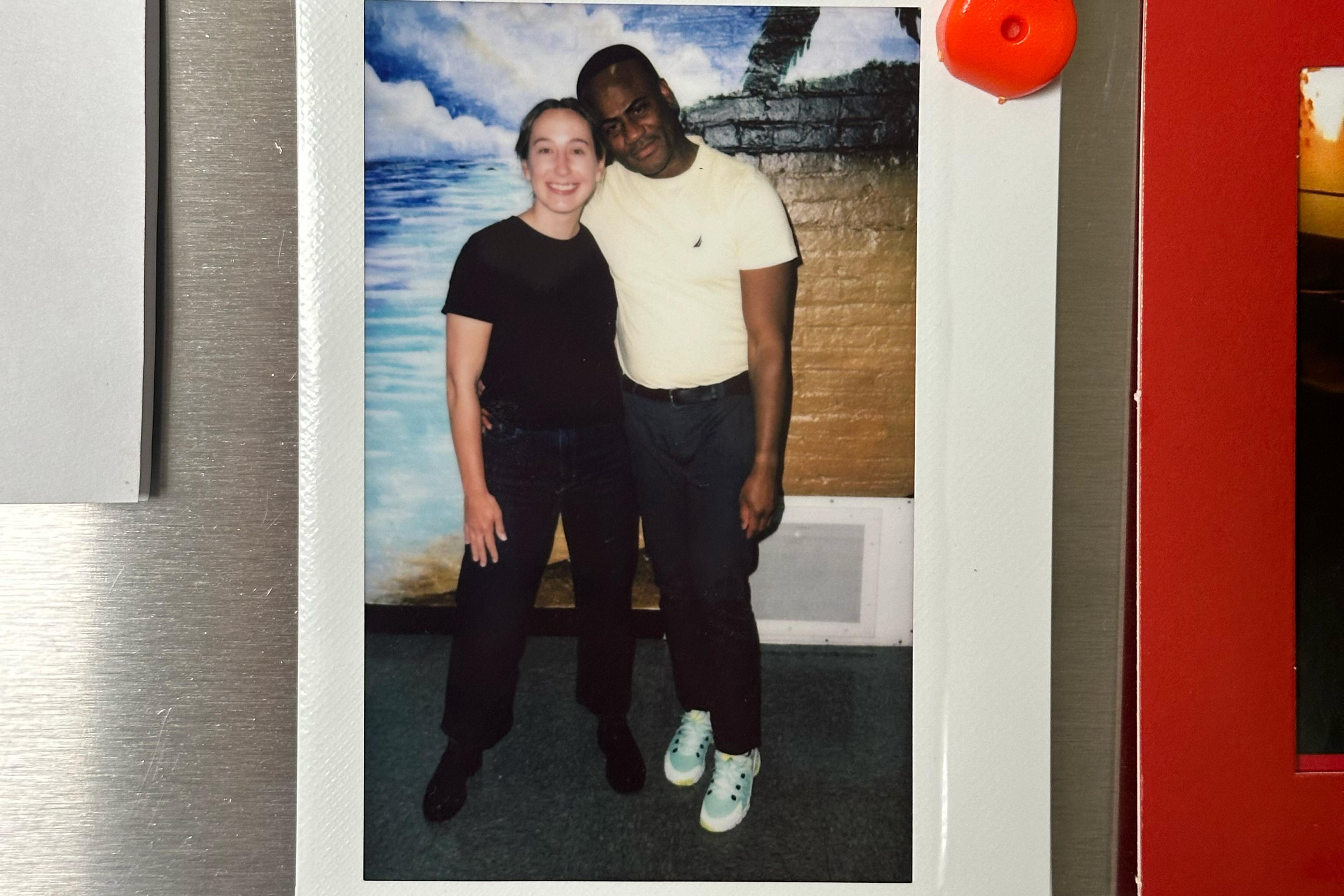

We trained more than 100 members in soapmaking that week. I met trans people for the first time in my life. I won’t lie: the attention I received was intoxicating too. By the end of the training, I joined Pema Kenya and as I write this, five years later, I am the chair of its board of trustees, an activist and a community paralegal.

I have since come out to all family and friends, and in fact to the world. In court, I learnt to speak up and speak clearly, learnt that others don’t have to believe me but still I must stand my ground, that the universe will always hold us even when others can’t – not out of malice but because life is happening to us all. I don’t know what that looks like for others but for me it is that I can laugh while telling this story. What I thought was broken was just a reconfiguration to help me fit in places I never knew I belonged or would ever have thought of reaching in life. As for the money that upended and ultimately enriched my life, what I had moved to a savings account is still being held there, frozen for the foreseeable future until the rightful owner claims it.