My 10-year-old is a kamikaze, swift and shrieking and inexorable as she flies down the stairs and into my father’s legs. ‘Oof!’ he says, stumbling back slightly. My mom follows him, shaking her head, rolling her eyes, reaching for a hug. I lean against the living-room doorway, sipping tea, watching the happy chaos.

‘Hello!’ I say, raising my mug in their direction. ‘Welcome to the madhouse!’

My father shrugs off his jacket and settles on to the couch with another Oof!, and Em immediately launches herself into his lap and lunges for his baseball cap. He pretends to be annoyed, waving the cap as she climbs him like a jungle gym, but he’s grinning like a loon.

God, my child is exhausting.

God, it’s good to see my father smile.

My mother sidles over to me. ‘We went to the neurologist today,’ she says, under her breath. She lowers her voice further. ‘The doctor says your father has Alzheimer’s.’

My father was diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment two years ago but I thought we had more time to somehow slow or even stop his decline. My mind churns through the implications. I know this diagnosis can mean everything from memory loss and confusion to personality and mood shifts. Will Mom continue to manage his care from home? Will we have to move Dad to a memory care facility? Will he let us?

I think suddenly of how I hadn’t even offered to embrace my parents when they arrived, hadn’t kissed them on their cheeks, and grief rears its head. When had we stopped doing that? And also, why?

I land, eventually, on fear.

Fear over losing my father, yes, but also over how ill-equipped I feel for what’s to come. I know how tireless and capable my mother can be in a crisis. But all I can think is that I am nothing like her, that I feel barely capable of handling my own life, my marriage, my career, my 10-year-old.

As I spiral, my mother lays a hand on my shoulder. ‘Should I tell your brother?’ she asks.

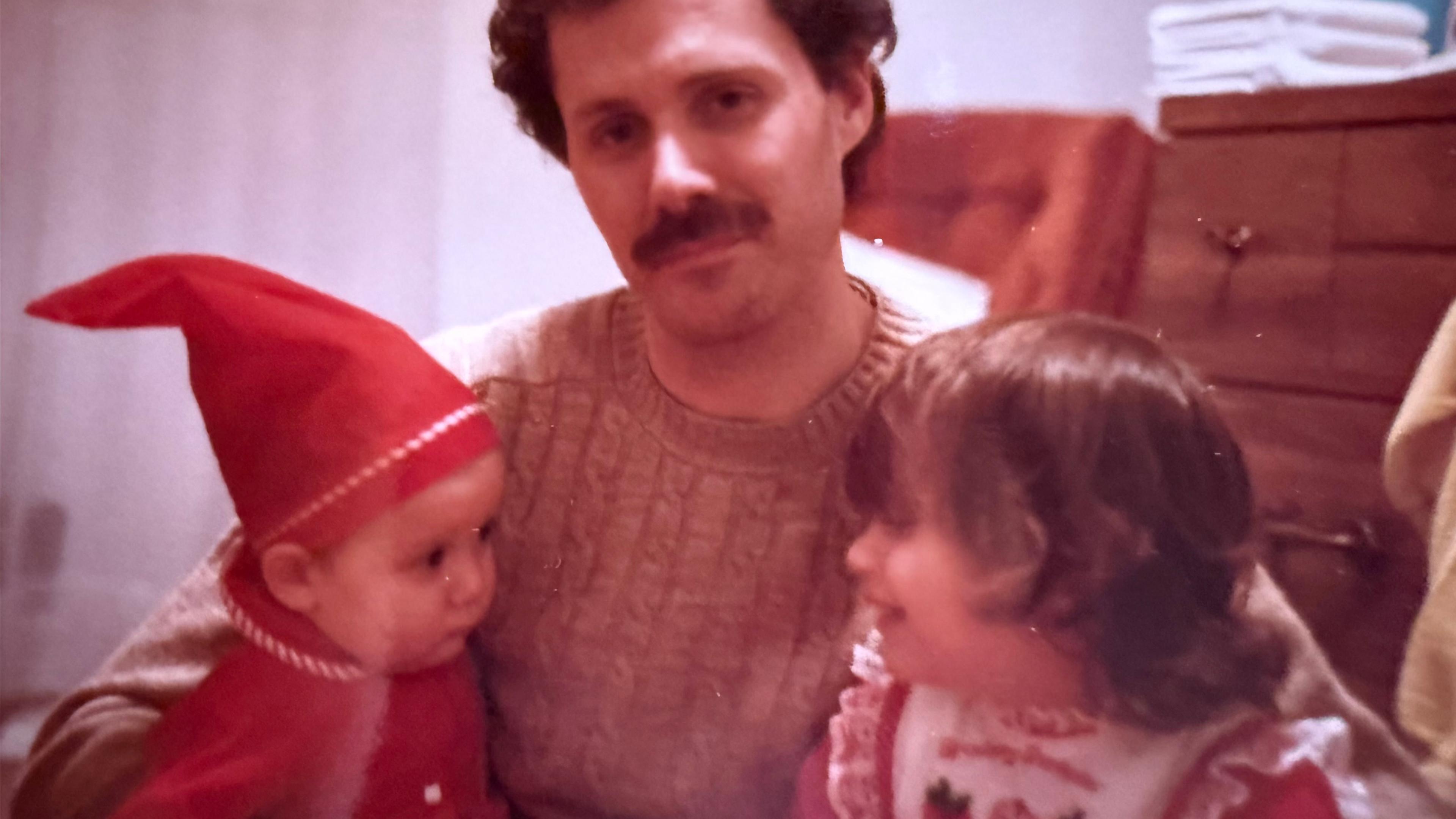

The author and her brother

My brother had stopped speaking to our parents first, cutting off their access to his children.

In texts with me, meanwhile, he’d pretended everything was normal. I’d found myself in a surreal state of dissonance, unsure how to raise a truth he refused to name.

Six months had passed before I finally saw him in person, and I’d pressed him on the matter. I already knew the tension between him and our parents was ostensibly due to differing expectations around discipline. My brother and his wife didn’t like our parents’ use of the word ‘can’t’, for instance, when they were babysitting. To me, this felt too trivial a reason to cut our parents out of their lives. But what my brother and his wife saw as repeated infractions eventually culminated in an incident in which my sister-in-law allegedly threatened to cut off my parents’ access to their grandchildren. My brother wasn’t there for the incident. My sister-in-law insisted it never happened. Things grew chillier between everyone. And now here we were.

Finally able to confront him in person, I’d pushed. Because it all seemed so arbitrary. My brother eventually admitted his wife had long felt my parents favoured me and my family. I found this ridiculous, and I was sick of talking in circles.

Just like that, my brother had erased himself from my life, too

‘What will you tell your children?’ I’d finally asked.

I was referring to his five-year-old son. His infant daughter.

He’d looked at me then, his face void of emotion.

‘They’ll forget eventually.’

Stunned, I’d locked myself in the bathroom, pressed my hands to my mouth, squeezed my eyes shut, and wept. After that, I stopped hearing from him, stopped receiving invitations to family gatherings. Just like that, he’d erased himself from my life, too.

More than two years later, as we wonder whether to tell him of Dad’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis, I am filled with rage whenever my brother crosses my mind. How dare he cut our parents out of his life, the parents who have done everything for him? How dare he abandon them when they need him most?

Then I realise my fury is a cover for grief. I always thought my brother and I would face things together. Sure, I was book smart, organised, the type of person you could rely upon to do the right thing. But my younger brother was the charmer, the handyman, the tech whiz – the one who actually fixed things. I think of us when we were young, following our father up the various hiking paths by the local quarry, him steadying us when our feet wobbled, urging us to search the underbrush for rocks and arrowheads. I think of us on snow days, clambering around the backyard, sliding in the wet and the cold, propping each other up, deliriously happy. I think of him more recently, building radiator covers for my new home when I was pregnant, helping my husband muscle heavy furniture up and down stairs.

Even now, whenever something notable happens in my life – new cats, Em moving up to middle school, a successful attempt at making raspberry swirl sherbet – I want to tell him. But then I remember: we don’t speak anymore. I hate living in this open wound: grieving a brother who lives a 15-minute drive away and a father who forgets more of himself every day.

Growing up, I’d watched my mother take care of her father, shouldering the visits, the daily phone calls, the difficult decisions. With her sisters across the country – and a career in nursing – she’d become my grandfather’s caregiver, by default. I remember sitting around the kitchen table for dinner as a teenager, the phone ringing, my father shaking his head because he knew it was my grandfather. Papa called every evening, his voice slurred from the alcohol his body could no longer process. I remember the wine bottles hidden in the backs of filing cabinets in his garage, the mini bottles tucked into the pockets of his suit jackets.

My mother snatched the phone from my father’s hand, the cord stretching across the room, and listened as her own father berated her: for controlling his life, for taking his car, for arranging his move to a senior care facility. ‘Have you been drinking?’ she whisper-shouted into the phone at one point, her brows drawing together, her voice a mix of anger, fatigue and helplessness.

This, I heard through the phone, was none of her business.

My father slammed his hand against the table – angry at my grandfather – and I flinched.

Is it possible for me to be a source of support to my parents without losing myself in the process?

Now, it’s happening again. My mother must care for another loved one, another person frustrated that he is losing his memory, his autonomy, himself.

I always thought my aunts owed my mom and my grandfather something more, even though they lived halfway across the country, with jobs and young families of their own. What did I expect them to do? And what do I – with my own various obligations – owe to my parents? Is it possible for me to be a source of support to my parents without losing myself in the process? This is what I want, but I worry about not being enough.

And as for my brother, what does he owe our parents? What does he owe me? Is there a chance that – in some reality, beyond what I can understand of his motivations – he is making the best possible choice for himself, and for his wife and children? I still can’t bring myself to see this estrangement as anything but a betrayal. It still hurts too much.

Meanwhile, I also wonder: is it OK that I have given up on him?

My mother reaches out to my brother to inform him of my father’s Alzheimer’s diagnosis, giving him a chance to say goodbye before our father forgets who he is.

‘Thank you for letting me know,’ he says, and then… nothing.

I tell myself I’m not surprised, that I no longer owe him anything.

My father, meanwhile – I owe him everything. What I am realistically able to give may look different, but I can drive him to appointments and ask his doctors follow-up questions, research senior day-programmes and home-health aides. I can invite him over to watch horror movies when my mom goes out, so he’s not home alone.

I can give him warm spring evenings with his granddaughter, the only person who can still make him smile. I can give him wiffle ball in the backyard, hot dogs and gravy fries at the picnic table, shitty jokes, and endless patience when he repeats himself. I can give him as many days as we have left together, as much as our days will hold.