Every day, collector friends send me ads for bizarre must-have items – micro pencil-lead sculptures, a Louis Vuitton ‘lobster wearable wallet’, 3D-printed ‘dragon eggs’. Granted, they’re not Stanley cups and Labubus but ‘weird stuff’ that by rights I should want too, as eccentric as I am. So I double-click the heart button and roll my eyes.

But I’m not a superior being; I’m also a compulsive collector of physical objects, as obsessive as my friends. I just don’t want that stuff. I’m a full-time artist and mudlark – one of those curious souls who scour the muddy banks of the River Thames at low tide, searching for lost and discarded artefacts that reveal fragments of London’s buried history. I collect the forgotten and the thrown-away: objects that connect me to the city and the people of its past. We mudlarks all have our favourite finds: gold and silver coins, precious glass intaglios, religious votive offerings, decorated clay pipes. Mine carry lasting emotional signs of long-gone humans, from medieval shoe leather impressed with the outline of a child’s foot, to glazed fingerprints indelible on ancient pottery, and a Georgian love token, hand-inscribed with a poem of undying devotion.

Before I became a mudlark, I was an urban explorer, slipping through abandoned military buildings in search of the lives left behind – medical instruments, engraved brass tags, personnel lists. Later, genealogy took hold, and I resurrected and catalogued other people’s forgotten family histories from documents unearthed in dusty shoeboxes in junk shops and flea markets. I gathered artefacts, but what I truly hunted were the people behind them.

The author in 1987

My motivation to recover material remains is deeply personal. I was a child of the early 1980s, raised in a typically dysfunctional, eventually fractured family, and I learned early to navigate the confusing adult world of my parents with care. Their rapidly changing relationships and opaque domestic arrangements were, at best, unconventional. Home life was unbounded and uncertain – caregivers came and went without warning – a strange and shifting reality for a young child trying to find something solid to hold on to.

Through years of instability, I clung to physical traces of those who would, inevitably, leave or let me down. An empty sugar sachet, secretly pocketed from a café meeting with a cousin I’d only just met; a half-used matchbook from a brief, happy stay with someone who might have become a new mother or father; a dog-eared photograph of Grandad and me, placed by Mum in his coffin and quietly retrieved when grieving backs were turned.

That instinct to hold on never really left me. What began in childhood as a way to anchor myself in a shifting world deepened through adolescence and into early adulthood, as loss became a familiar companion. My teenage and young adult years were marked by a temporary estrangement from my father, the deaths of close friends from suicide, the pain of my own pregnancy terminations, and abusive relationships. I clung to symbolic, physical remnants of those who drifted out of my life, as if holding their objects might confirm they had once truly been part of it. Over time, I realised my mudlarking finds are remnants too – forlorn brothers and sisters of the intact artefacts displayed in museums, each broken piece carrying traces of the lives it once touched. Shattered vases, dented buttons, splintered combs – all echo human fragility, each one a small reflection of loss and endurance.

My Freudian Friend, OK, my therapist, tells me I find human interaction overwhelming and confusing, so I substitute the emotional with the inanimate. It’s true, I’m suspicious of everyone, always looking for the conversation behind the conversation – what is really being said, what is really meant. This questioning and answer-seeking process is mirrored in my artefact research methods, starting with the diagnostic features of an object. Its shape, size, type, does it have a surname, date, maker’s mark? I cross-reference with written archives, finding full names, addresses and sometimes even portraits.

I am just another person, a link in this ongoing, intergenerational chain of stories

I connect objects with research, tracing their clues back to the people who once held them. A broken piece of a beer jug from a dockside tavern, its glaze marked with a faint street name, leads me to an 1869 inquest into the death of an unwatched child – a hearing held in that same tavern, then called the Bull and Butcher. I visit the postwar building that now stands in its place with the sharp-edged ceramic in my hand. Touching the cobbled pavement, I can almost sense the ghosts of both child and coroner lingering there.

A lemonade bottle, its vulcanised rubber stopper still faintly embossed with the name ‘Whiteleys’, leads me to the story of the department store mogul William Whiteley, fatally shot in 1907 by his alleged illegitimate son – enraged after Whiteley’s flippant dismissal: ‘I must not mix myself up with what has passed.’ Another potential sliding-doors moment flashes before me: if my mother had walked out all those years ago, would I be searching the globe for her now, grievances in hand? Uncovering complicated lives and interpersonal relationships confirms that I am just another person, a link in this ongoing, intergenerational chain of stories.

Ten years into my mudlarking hobby, I’m a collector with a storage problem, and the uneasy feeling of having taken too much from the river. Just how many decorated buttons, ornate earthenware floor-tile fragments, intricately patterned glass trade beads, does a person need? Jabbing at my mind throughout my many years of collecting, the words of Lao Tzu: ‘When gold and jade fill the hall, their possessor cannot keep them safe.’

So I attempt to whittle down my collection to bare bones, following a new set of rules: only one example of each type of find – one exceptional piece of decorated Roman pottery, one remarkable 18th-century shoe buckle, a singular delicate apothecary bottle, a sole beautiful ammonite fossil. The rest of my collection I intend to donate to Young Archaeologists’ Club groups, museums, and schools. I will take a small amount of finds back to the river, scattering them where I originally picked them up.

Perhaps this is the thing I had been seeking in strangers’ stories all along

I condense my refined collection into six stackable, compartmentalised wooden market crates, the kind used at Covent Garden in the 1940s, when, with impeccable timing, my father turns up, and thrusts a battered old suitcase of family heirlooms in my direction. ‘There you go, girl!’ This case of precious artefacts includes an airgun pellet shot into Dad’s head by a childhood friend, my grandmother’s parachute-silk wedding dress, letters from an uncle who died a prisoner of war in Changi, and the enormous early 19th-century ‘family Bible’. Some small irony here that we are none of us religious. I feel a wave of impending doom. More ‘stuff’ to cart around for the rest of my natural life, fearful of inadequately protecting it. More pertinently, it means rifling through my own, very real, family history this time, not someone else’s. Perhaps this is the closest thing to proof of my own identity – the thing I had been seeking in strangers’ stories all along.

The author’s ancestors, c1900

Dad is as unmoved by our family relics as he is by the rural Hertfordshire landscape of his youth. His childhood bungalow – a rare oasis of calm amid my own chaotic upbringing – stood in wide fields and wildflower lawns, yet he sold it without hesitation after his parents died. While he resists nostalgia, I’ve always leaned toward it. My grandparents’ village held its own quiet magic: Second World War bunkers in the woods, the medieval church rumoured to contain a giant in its walls, long silent afternoons with my grandmother, whose gentle wistfulness showed me that even beautiful places carry shadows of loss.

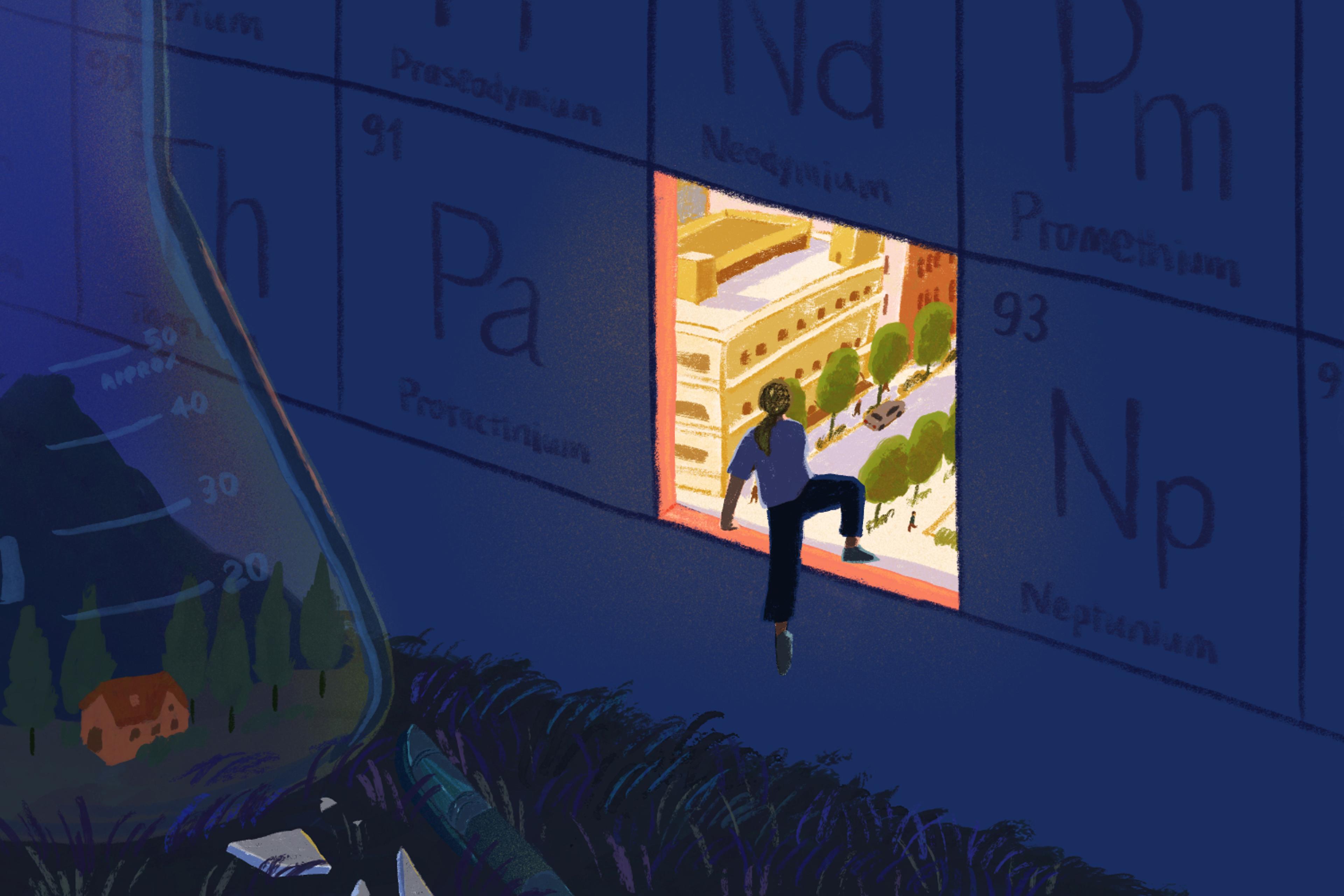

Though originally a country girl, I left at 21 to ‘find myself’ in London. I worked in arts and heritage, but the suspicion that I was playing a role never left. Returning to rural communities over the years became a way to breathe outside my constructed city identity – a reminder of the person I might have been if life had unfolded differently.

Recently, walking the footpaths of my childhood, I felt a bolt of recognition. Rusted farm machinery still stood in the same field; the old railway bridge looked unchanged. I thought of the day I found a ginger cat seemingly asleep there – the first dead animal I ever touched – and the news, a few hours later, that my grandfather had died. I remembered standing by the River Ouse, throwing in my Barbie doll and then myself so my father would wade in after us. These memories rose with a force I hadn’t expected, an overwhelming sense of belonging that swept through me as if the land itself had tapped my shoulder. Roots I’d spent years seeking in other people’s stories were here all along.

The urge to fill the gaps in my identity with objects dredged from the river has eased

On returning to London, I made the abrupt decision to dismantle my city life and go home, to a chorus of ‘Have you lost your mind?’ A mudlark miles from the Thames, I felt no fear – only a clear, steady understanding that my search had shifted direction. The compulsion to hunt for fragments of strangers’ lives had ebbed; I finally felt ready to turn toward my own.

Preparing to move meant confronting the crates of artefacts I’d already pared back. Even reduced, they looked less appealing when imagined in a new life. I briefly considered destroying everything, starting from nothing – but absolute erasure felt as disturbing as hoarding. Instead, I chose a gentler middle ground: keeping only the things I missed when they weren’t in sight and releasing the rest in small ‘deposits’ along roadsides, leaving curious objects to be discovered by future scavengers.

I whittled six crates down to four. Into them went a deliberately chosen mix of river finds and my father’s battered suitcase of family history. They’ll accompany me to my new-old home as quiet witnesses, not proof of who I am.

I’ll still visit the Thames, though less often and with lighter hands. The urge to fill the gaps in my identity with objects dredged from the river has eased. For the first time, I feel able to look directly at my own past – no artefacts needed.