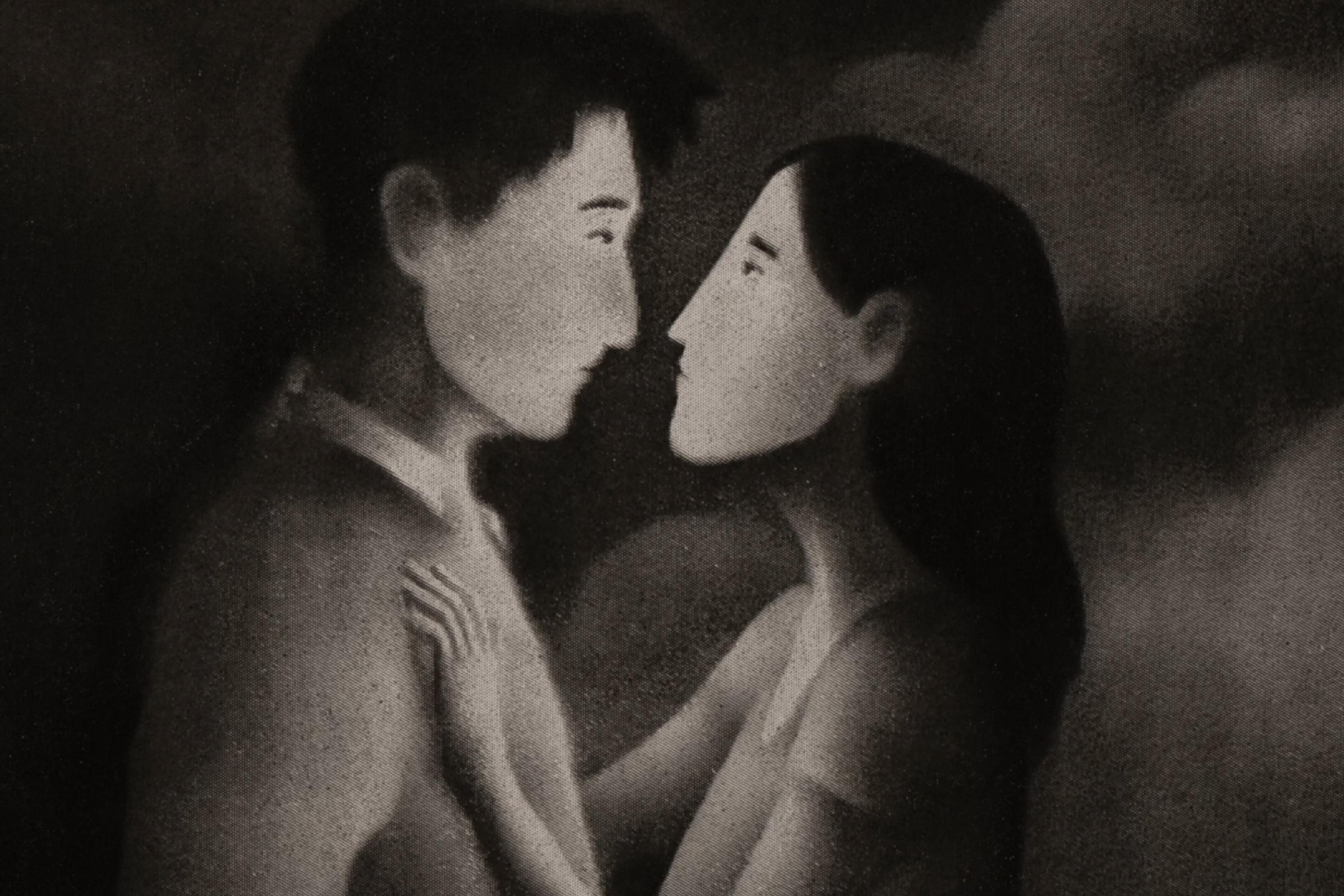

In a creamy, cloud-soft world, a solitary being, a face as monochromatic as its surroundings, placidly eats, exuding comfort and ease. Moments later, a multi-hued face appears, sending from its mouth a wriggling red line that enters the back of the pale being’s head, emerges from its cheek and moves to its lips, transforming them. Does this sound familiar? Perhaps not, but it’s the beginning of a classic – a story of love.

The British Sri-Lankan filmmaker Anushka Naanayakkara made her BAFTA-winning stop-motion animation A Love Story while studying at the National Film and Television School in the UK, basing the film on a personal experience. If the narrative is hardly new, Naanayakkara’s rendering of it is strikingly original – an intense distillation of a relationship.

Eschewing contextual explanation, backstory and psychological characterisation, Naanayakkara freshens the love-story schema with her own imaginative interpretation of what a relationship looks like in its most basic terms. The achievement is not just one of efficiency and concision, though. Naanayakkara’s take on the arc of meeting, falling in love and breaking up also has the potent specificity that makes a good love song or poem speak so directly to people with divergent experiences. She does this without any words, finding instead a distinctive way to convey the relationship’s contours solely in images and sounds.

For someone who identifies with either or both of the beings in some way, the unfolding relationship – the evocatively familiar aspect of the film – might summon memories or elicit emotions connected to their own experiences of love. But the tension between understanding perfectly well what’s going on and the concurrent oddness of what we’re seeing offers another way in as well. By making the familiar fantastical and strange, Naanayakkara gives us enormous latitude to use our own imaginations to shape the love story in our fashion.

Using wool as her medium, Naanayakkara creates a world that is simultaneously tactile and airy. The varied textures of the yarn accentuate physicality in the relationship of the two lovers, but not in a conventional sense of sexual intimacy. These beings are, after all, only heads, so the physical connection is peculiar. The coloured lines between the beings could symbolise feelings, no doubt, but they also look biological, maybe a poetic visualisation of the ‘neurobiology of affiliation’, the neural, endocrine and behavioural systems underlying the capacity to love.

At the same time, the wool’s lightness gives a sense of ephemerality and mutability. We constantly see small shifts in the material. Sometimes these signal changing emotions and expressions, but just as often they don’t represent anything that can be explained straightforwardly. When the relationship starts to come undone, the dark wool that begins to obscure the multihued face seems both a physical affliction and representative of an internal state. Does it mean that the two beings just stop loving each other? Does poor health push them apart? Do they lose their ability to communicate?

In a sense, Naanayakkara gives us only abstracted, visible manifestations of each phase of the relationship, leaving open cause and effect, perhaps even the possibility that a different logic of interaction holds sway between these two beings. Without prescribed significance, we can make our own linkages, interpolate our own interpretations. It’s as if the film itself is a tight jazz combo and we’ve got the wonderful freedom to improvise on top of their chord changes – or just sit back and enjoy the piece.

For all this interpretive leeway, the film does seem firm on at least one matter: love is fundamentally transformative, active. Each of these two lovers is marked by the other, an idea that Naanayakkara shows through the beautifully strange repetition of a single strand of yarn going from one being’s mouth and turning into a little cross-stitch on the other’s face. Like a line from a poem or song that stays with us, this image has that kind of singular resonance to mark us too.

Written by Kellen Quinn